Images: Hops by John Navajo; Hemp by Dmytro Tyshchenko/Shutterstock

Why are some plants–and the substances derived from them–beloved and broadly-embraced, while others are vilified, restricted, and viewed with suspicion?

The reflexive answer might be: Some are dangerous, while others are beneficial. But if you take a deeper look, it’s seldom so simple.

As an herbalist, I am prone to questions like this. And lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about the unique and different fates of Hops (Humulus lupulus) and Hemp (Cannabis sativa)–two widely cultivated and distributed plants here in the US, and abroad.

Many people don’t know that these two are related. They belong to the same plant family, Cannabaceae, and of the higher order Urticales. Let’s think of them as sisters sharing similar genetics and traits.

Hemp and hops both have flowers that we humans have used—and abused—owing to their calming and intoxicating effects. The flowering parts of Humulus lupulus and Cannabis sativa both produce trichomes containing resinous substances, and over the centuries, we have cultivated and bred both of them for specific morphological traits or organoleptic characteristics.

But from a legal and regulatory perspective, these two sisters have been treated very differently here in the United States and in other parts of the world.

Divergent Histories

For the last 150 or so years, up until very recently, cannabis has suffered stigmatization, criminalization, and scorn in the US, while its sister—Hops–on the other hand, has long been a key component in a multi-billion-dollar legal consumer alcoholic beverage market.

One report estimates that the global beer market reached $189 billion in 2020. That’s roughly nine times the estimated $21.3 billion for legal cannabis sales last year.

Beer would not be beer without hops. The alpha acids in hops flowers, especially humulone, and the sesquiterpene, humulene, are the main phytochemicals studied in beer. They minimize the growth of unwanted bacteria, regulate foam production, and give beer its characteristic aroma and flavor.

Compounds within Hops also have a calming effect, though this is not generally the reason for including them in beer recipes.

The German government’s Commission E —an internationally recognized authority on the evidence-based use of medicinal plants—approved the use of hops for mood disturbances such as restlessness and anxiety as well as sleep disturbances. Though not as widely known as Chamomile (Matricaria camomillia), Valerian (Valeriana officinalis), and other plants with calming effects, is not unusual to find hops in herbal formulations that “support a good night’s rest.”

The pharmacological mechanisms of action for hops and extracts of hops are still unclear, though that has not limited their use in many accepted traditional pharmacopeia (Chadwick, L R et al. Phytomedicine: Intern Journal Phytother and Phytopharmacol. 2006).

As a commercial crop, hops have a welcome place in the nation’s economy, as well as it’s pantry. Unlike its botanical sister, this member of the Cannabaceae family has never been marginalized or criminalized.

Hemp’s Rise and Fall

Hemp was not always frowned upon. In fact, it was central to the economy of the early US. During the colonial period, and up until the Civil War era, hemp was widely cultivated as a fiber crop. It was essential for making fabric, rope, twine, and sails.

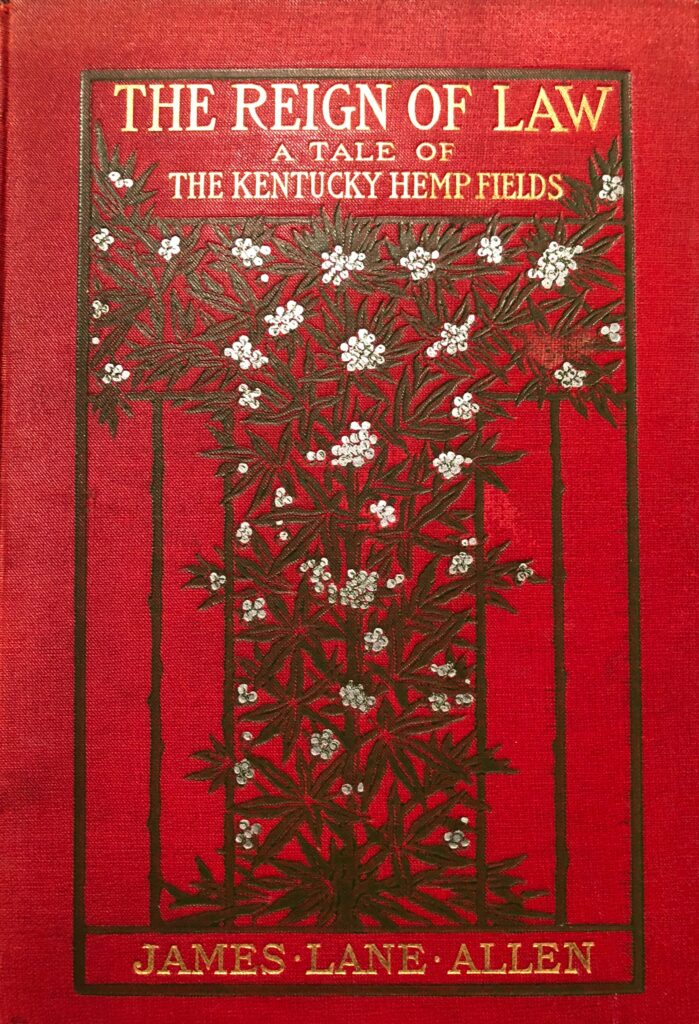

In the opening chapter of his 1900 historical novel, The Reign of Law: A Tale of the Kentucky Hemp Fields, American author James Lane Allen underscores the economic importance of hemp, especially in middle Southern states like Kentucky:

“The record stands that throughout the 125 odd years elapsing from the entrance of the Anglo-Saxon farmers into the wilderness down to the present time, a few counties of Kentucky have furnished army and navy, the entire country, with all but a small part of the native hemp consumed.”

It took roughly 120,000 pounds of hemp fiber to rig the USS Constitution, aka “Old Ironsides,” and that’s not including the sails and the caulking, which were also made from hemp.

But by the middle of the 1800s, hemp fiber was largely supplanted by cotton, and hemp-based agriculture suffered a long, slow decline. It no longer had the same industrial impact, though its resinous flowers and leaves were certainly valued by many for their psychoactive properties.

Hops, Hemp & the ECS

The flowers of Cannabis sativa L. (Hemp) produce a host of biologically active phytochemicals. Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannibidiol (CBD) are certainly the best known and most popular. They’ve also recently been adopted into the manufacturing standards for botanical preparations of hemp, which have become extremely popular with consumers and practitioners.

But there’s far more to this plant than just THC and CBD. Cannabinoid research is booming worldwide, as investigators discover more about these compounds and their receptors within the human nervous system.

Both hemp and hops produce compounds that love to interface with the human endocannabinoid system (ECS), and we are learning more and more about the ECS every day as manufacturers and scientists’ race to understand this gateway to so many other major biochemical and physiological systems.

These two sisters also produce a variety of interesting mono- and sesquiterpene compounds. Myrcene and beta-pinene are found in both hemp and hop buds. These chemicals give both plants their distinctive aroma. Other shared terpenoids include humulene and beta-caryophyllene.

In the characteristic flowery prose of his era, James Lane Allen describes this olfactory phenomenon:

“And now, borne far through the steaming air floats an odor, balsamic, startling: the odor of those plumes and stalks and blossoms from which is exuding freely the narcotic resin of the great nettle. The nostril expands quickly, the lungs well out deeply to draw it in: fragrance once known in childhood, ever in the memory afterward and able to bring back to the wanderer homesick thoughts of midsummer days in the shadowy, many-toned woods, over into which is blown the smell of hemp fields.”

From Commerce to Criminalization

The criminalization of cannabis began in the early 1900s. The crop had dwindling value for fiber, but it remained somewhat popular for recreational and medicinal use—in certain communities.

By 1906, various states began redefining Cannabis sativa as a drug and/or poison, and by the 1920s, many states prohibited the cultivation, possession, and personal use of cannabis.

Then came the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937, a nationwide move which levied heavy taxes on the sale of cannabis, also known as “Indian hemp” back then. The legislation was spearheaded by Henry J. Anslinger, the first commissioner of the US Treasury Department’s Federal Bureau of Narcotics.

Anslinger was a prohibitionist firebrand who laid the groundwork for the so-called “War on Drugs” that continues today. He was no friend of alcohol, but he had a special contempt for cannabis—and the people who used it. In radio PR campaigns described it as:

“the deadly, dreadful poison that racks and tears not only the body, but the very heart and soul of every human being who once becomes a slave to it in any of its cruel and devastating forms. … Marihuana is a short cut to the insane asylum. Smoke marihuana cigarettes for a month and what was once your brain will be nothing but a storehouse of horrid specters. Hasheesh makes a murderer who kills for the love of killing out of the mildest mannered man who ever laughed at the idea that any habit could ever get him.”

It is interesting to note that at the time, the Marihuana Tax Act was opposed by the American Medical Association because the tax applied to physicians and pharmacists who prescribed and dispensed cannabis and its derivatives.

But the tax had powerful allies, including business magnate Andrew Mellon, newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, and the DuPont family. Hearst was not pleased about the development of the decorticator—a device that mechanically stripped hemp fiber from its stem, a job that previously had to be done by hand. A re-emergent hemp industry that could easily produce hemp paper was a threat to his holdings in timber for wood pulp.

The DuPonts were heavily invested in developing synthetic fibers like nylon. The possibility of a re-emergent hemp fiber industry did not appeal to them. Mellon, who was Secretary of the Treasury at the time, was heavily invested in the DuPont company.

Facing Racism

Business interests drove the tax, but the cultural vilification of cannabis as incited by Anslinger and his allies, was driven by a different motive: racism.

Historically, use of cannabis was common among people of African, Latin American, and Asian descent, and it has a long tradition of medical and recreational use in many parts of Africa, Asia, South and Central America, and the Caribbean.

But unlike beer and other forms of alcohol made from fermented grains, cannabis was never part of the cultural heritage of Northern Europe.

To the dominant US culture—White and of Northern European descent—use of cannabis was “other.” It belonged to the dark-skinned people. In his book, Allen points out that the Anglo-Saxon hemp farmers of Kentucky had no interest in the flowers and leaves of the plant, pointing out that:

“the whole top being thus otherwise wasted—that part of the hemp which every year the dreamy millions of the Orient still consume in quantities beyond human computation and for the love of which the very history of this plant is lost in the antiquity of India and Persia, it’s home—land of narcotics and desires and dreams.”

The criminalization of cannabis went hand in hand with the stigmatization, marginalization, and criminalization of African-Americans, Latin Americans, and Asian and Southern European immigrants. Hops, the sister Cannabacean, also produces mildly intoxicating compounds. But nobody ever went to jail for cultivation or possession of hops.

Anslinger and the early drug warriors tried hard to make a public health case for criminalization, insisting that cannabis was a dangerous, addictive drug that destroyed health and predisposed people to violent crime.

Some physicians at the time, including the AMA’s own attorney, Dr. William Creighton Woodward, refuted Anslinger’s claims as unscientific and nonsensical. They were largely ignored.

Winds of Change

Today, one would be hard-pressed to convince anyone that cannabis use is inherently more dangerous or “criminal” than drinking beer. But hemp in all its forms still carries a stigma that hops never had.

Currently, hemp has three approved uses as an ingestible substance in the US: Hulled Hemp Seed (GRN765), Hemp Seed Oil (GRN778) and hemp Seed Protein (GRN771).

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018 (S.3042), enacted by the 115th Congress of the United States in 2017-2018 and referred to as the Farm Bill, defines and permits the cultivation of industrial hemp (low-THC producing cannabis), but defers regulatory authority to the individual states. All over the US, the rules are in flux. Industry trade groups have coalesced to persuade FDA to deliver clear policy guidelines.

Laws governing the medical and recreational use of high-THC cannabis, and even low-THC cannabidiol (CBD), are highly variable from state to state. The one exception is Epidiolex, a prescription CBD product approved by the FDA in 2018 for treatment of certain types of epilepsy.

But as more states legalize cannabis, it is clear that attitudes are changing. Though many Americans still view cannabis with suspicion, it is not nearly the dangerous “other” that it was portrayed to be in the 1930s and 1940s.

I don’t think it is coincidence that the increasing acceptance of cannabis is happening at the same time as our collective reckoning with the ongoing legacy of racism, and with issues of ethnic and cultural diversity. Both are movements in the direction of healing, inclusion, and the righting of historical wrongs.

We can envision the day when hemp rejoins its sister, hops, as an ordinary crop free of stigma. Likewise, we can envision—and work toward—a future in which all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, or gender are safe, respected, and treated fairly under the law.

END

Bill Chioffi is the Vice President of Strategic Partnerships & Business Development at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine (SCNM), where he heads development efforts for the college’s new Ric Scalzo Institute for Botanical Research. Prior to joining SCNM, he was the VP of Global Sourcing and Sustainability at Gaia Herbs, one of the nation’s top producers of herbal medicines. He serves on the boards of United Plant Savers, the American Botanical Council’s Sustainable Herbs Project, Appalachian Forest Farmers, and previously held a seat on the Executive Committee of The American Herbal Products Association (AHPA).