How did the most sophisticated and scientifically advanced medical system of its time become an agency of systematic state-sanctioned mass murder?

It’s a question that haunts anyone who looks at the history of medicine during Germany’s Third Reich. And it is the subject of a comprehensive new report from The Lancet.

Issued in early November, to coincide with the 85th anniversary of Kristallnacht—the violent pogroms generally considered to be the start of the Nazi effort to exterminate the Jews —The Lancet’s report is the most thorough exploration of this troubling subject to date.

Richard Horton, MD, The Lancet‘s Editor-in-Chief, convened the 20-member Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust to develop “a reliable, up-to-date compendium of medicine’s and medical professionals’ roles in the development and implementation of the Nazi regime’s antisemitic, racist, and eugenic agenda, which culminated in a series of atrocities and, ultimately, the Holocaust.”

Co-chaired by medical historians Herwig Czech, of the Medical University of Vienna, and Shmuel P. Ries, MD, of the Hebrew University Hadassah Medical School, Jerusalem, the commission included physicians, historians, and medical ethicists from Austria, Spain, Germany, Israel, Czech Republic, Poland, and the United States.

“Medical crimes committed in the Nazi era are the best-documented historical example of medical involvement in transgressions against vulnerable individuals and groups. What happened under the Nazi regime has far-ranging implications for the health professions today, and virtually every debate about health professional ethics can gain from an understanding of this shameful history,” the authors write in their introduction.

The Lancet report emerges at a time when many people glibly throw around terms like “Nazi” and “genocide,” and “concentration camps” in political discourse to support a range of often opposing causes and positions. Deliberately inflammatory use of such words is clearly displayed on both sides of the discourse about the current Israel-Hamas conflict.

Just 3 years ago, the same sort of button-pushing language arose during the Covid pandemic, when some opponents of vaccine mandates invoked the specter of Nazi medical experiments to make their case. It has come up repeatedly in debates about healthcare reform, where opponents of national healthcare decry “government death panels.”

The Lancet’s report also comes at a time of widespread Holocaust denial, when the ranks of those who actually experienced the horrors of World War II are growing thin, and the global geopolitical order is increasingly unstable.

In light of all of this, it behooves us all to learn what actually happened in Germany and surrounding countries from 1931 to 1945.

Exclusion From Healthcare

The atrocities of the Holocaust were the culmination of longstanding cultural and political movements in which “science, medicine, and public health were used to justify and implement persecutory policies and eventually state-sanctioned mass murder and genocide.” The Lancet committee defines the latter term as “the targeted murder of specific religious, racially defined, national, or ethnic groups.”

The report traces the origins of these movements from their roots in late 19th Century European “race science,” through their dissemination during the tumultuous Weimar-era of German history, and ultimately through their operationalization as national policy after 1933, when Hitler took power as Germany’s chancellor.

The Weimar period was a time of great political and economic strife in Germany, and in much of Europe. It was also a time of rapid scientific and technological advances, as well as social change. During that period, the ranks of German medicine included a growing number of Jews, women, and non-German immigrants. The Lancet report cites a 1933 German census showing that while Jews comprised roughly 1% of the nation’s population, they represented roughly 10% of its doctors. Not everyone was happy about that.

One of the new Reich’s first formally racist anti-Jewish policies was a general boycott of Jewish-owned businesses–a call that explicitly mentioned Jewish physicians’ practices.

This was quickly followed by the 1933 Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, which forbade Jews from holding positions in the civil service, including the public health service, and at universities, which included medical schools. The Lancet committee states that this led to the immediate dismissal of nearly 20% of all people working in academia, 80% because they were Jews and 20% because they were deemed enemies of the Nazi regime.

Further legislation in April and June of 1933, explicitly excluded Jews and other “political opponents” from receiving payments from the nation’s health insurance system. By 1938, the Reich stripped all Jewish physicians of their medical licenses, made it illegal for them to call themselves doctors, and forbade them from treating non-Jewish, ethnically German patients.

From Genetics to Genocide

Though extermination of Jews was always part of Hitler’s plan, the industrial scale mass murder that we’ve come to know as the Holocaust did not begin with Jews, or for that matter, with the Roma, Sinti, homosexuals, or political prisoners all of whom ultimately became victims of the Nazis’ agenda. Rather it emerged out of the Reich’s eugenics program, and it began with forced sterilization of people with physical disabilities and psychological disorders.

At the core of the Nazi ideology was the concept of the Volk—a idealized, heroic, racially superior German people that had been unjustly dethroned and debased by an “international order” imposed by the Allied powers after World War I, and which must re-assert its dominance first in the German homeland, then in Europe and beyond.

This doctrine was framed in a context of racial hierarchy, defined according to a set of physical, mental, and temperamental traits. The so-called Aryan and Nordic races at the top, and the African races, as well as the Slavs, the Roma, and the Jews, were at the bottom. Hitler and the Nazis held a particular contempt for Jews, blaming them for Germany’s defeat in WWI and labeling them as a nefarious racial “enemy within” bent on weakening and destroying the Volk.

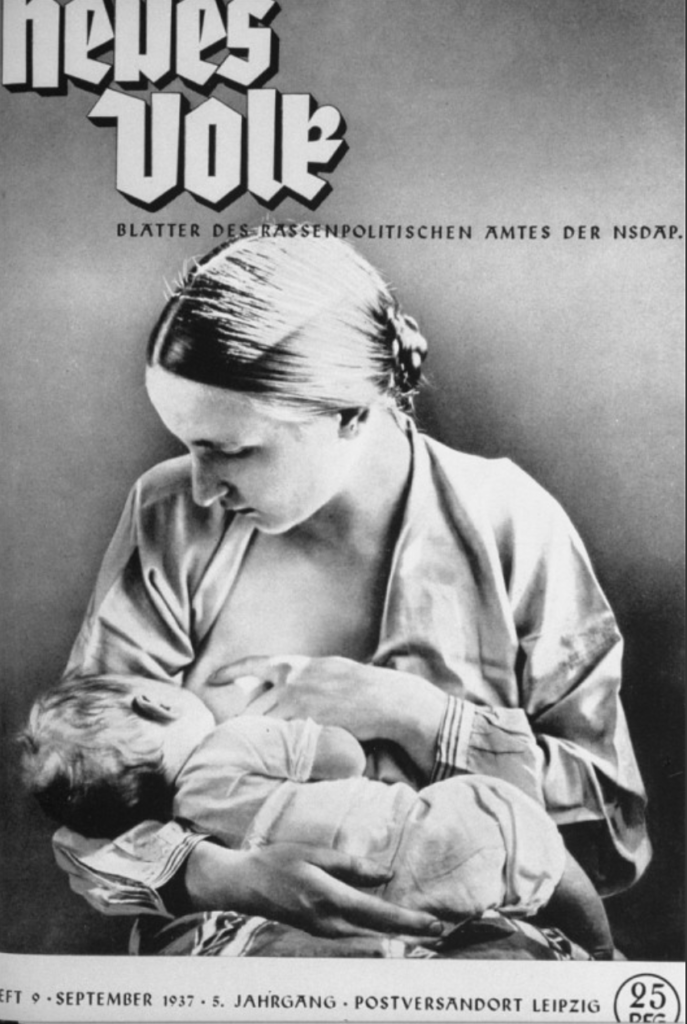

Central to Nazi policy was the notion of “racial hygiene” (Rassenhygiene), a medico-social ideology rooted in genetics and social Darwinism, which viewed human affairs as an existential competition between races, and which obligated the German Volk to promote procreation of its most “fit” people, while simultaneously purifying itself from those deemed “racially undesirable” or “genetically unfit.”

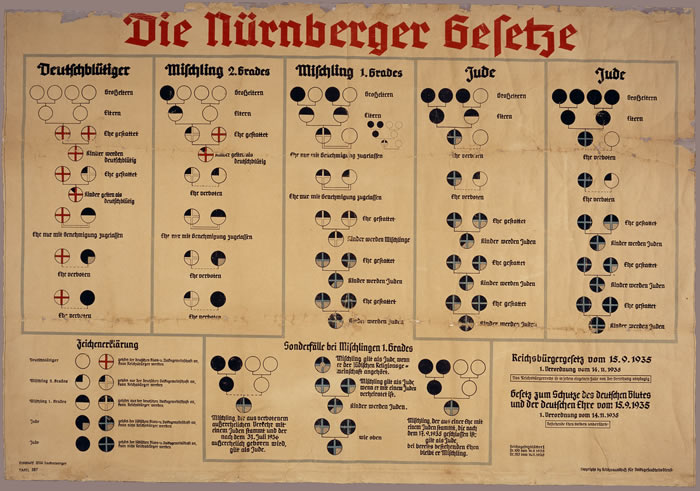

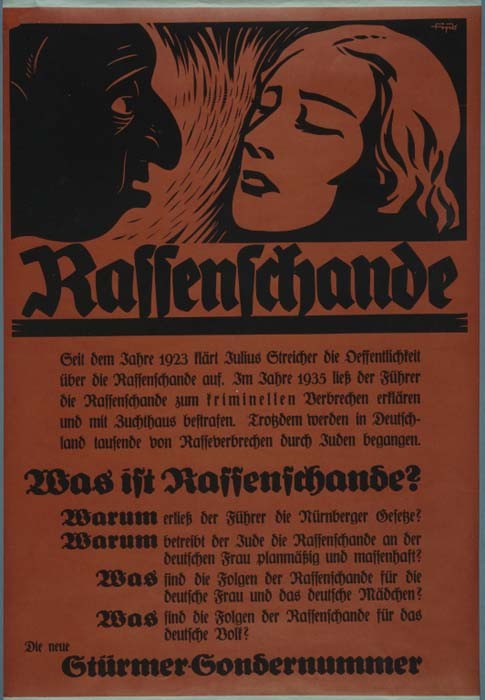

This was formerly codified in the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which stated that only people of “German or related blood” were eligible to be Reich citizens, and which forbade intermarriage and interracial sexual intercourse. It also imposed a wealth tax of up to 90% on Jews or any other newly disenfranchised people who sought to emigrate out of Germany.

Under these laws, couples had to obtain certificates of “biological fitness” before they could marry. Access to all public social support services was closed to all individuals deemed impure or unworthy.

Responsibility for enforcing the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour –one of the two key Nuremberg Laws–fell largely on the public health offices. The practice of medicine in this context became an endeavor to strengthen the Volkskörper (the German national body) and prepare it for the arduous task of conquest and empire-building.

A 1939 public health service handbook stated that “Every measure, undertaken in all areas, must be examined from the point of view of population policy, and care for heredity and race.”

In essence, the Nazi racial hygienists—many of whom were physicians–sought to apply principles gleaned from the nascent science of genetics, and from centuries of animal husbandry, to control human reproduction. The Lancet report notes that Rudolf Hess, Hitler’s deputy Führer, once described National Socialist doctrine as, “applied biology,” and called the regime a “biopolitical dictatorship.”

“Applied Biology” & “Ballast Lives”

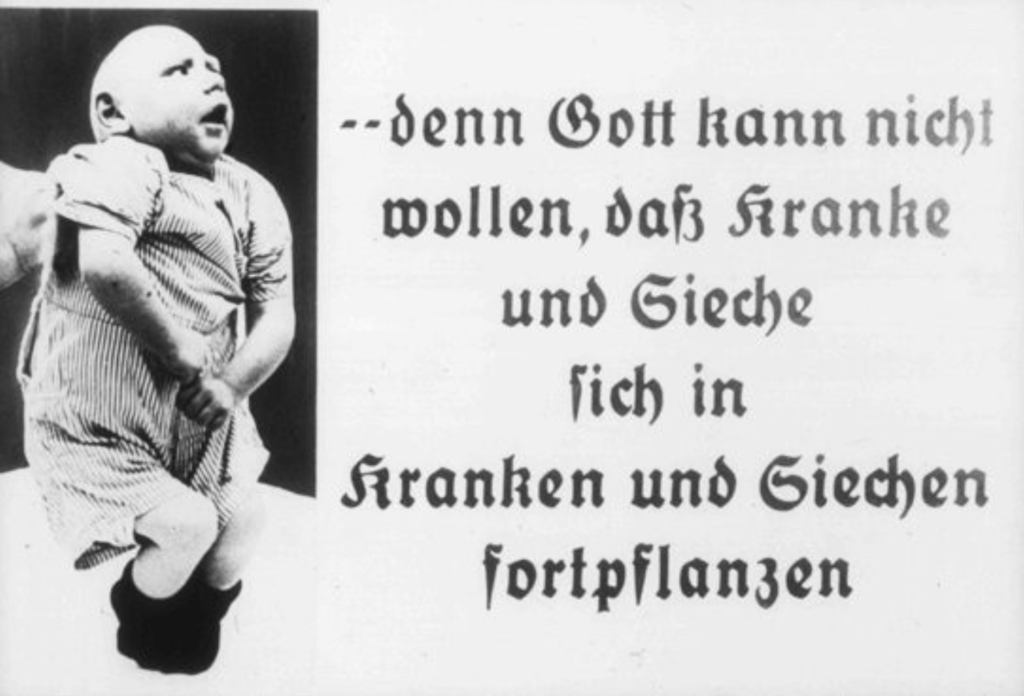

Eugenics was the practical manifestation of racial hygiene. By 1931, even before Hitler took power, the writings of three German racial theorists—Erwin Baur, Eugen Fischer, and Fritz Lenz—were compiled into a multi-volume textbook, the title of which translates as: Human Heredity Theory and Racial Hygiene

This book was a cornerstone of Nazi public health policy. It codified the notion that left unchecked, “lower races” could—and would—contaminate “higher races” leading to physical and social degeneration. To prevent this, the racial hygienists called for the outlawing of racial mixing, and the elimination of “counter-selective forces.” That meant people of mixed-race heritage, people with hereditary illnesses, those with physical or mental disabilities, and those with irremediable character flaws like alcoholism and drug addiction.

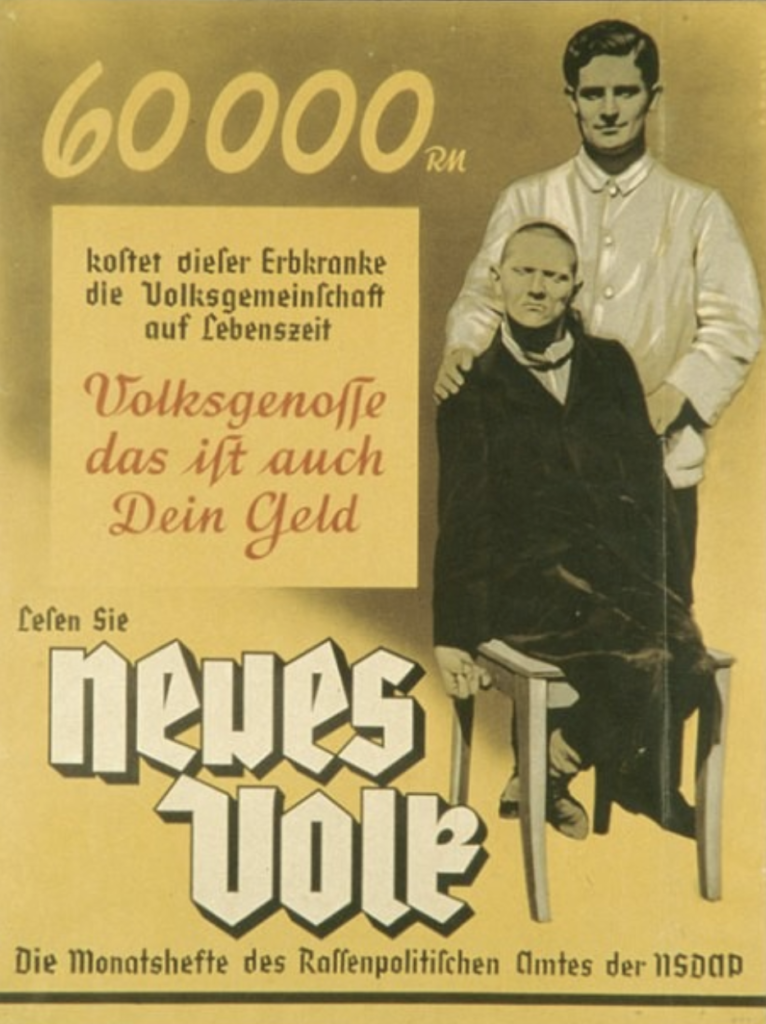

These people were considered “ballast lives” (Ballastexistenzen)”—people with no inherent worth, who weighed down the healthy body politic.

The Reich enacted the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring in 1933, which called for the forced sterilization of women and men who were physically or mentally disabled, “criminally insane,” or “feebleminded.” That latter was a catch-all term applicable to many different types of people the regime considered unworthy.

“Physicians (especially psychiatrists) and other health professionals not only spearheaded the crafting of the sterilisation law, but also played crucial roles at each step of implementation. Their contribution to the law’s enforcement began with the mandatory reporting of patients judged to be hereditarily diseased,” write the Lancet commission authors. Medical practitioners also carried out the sterilization procedures, typically done surgically or via x-ray exposure.

The Lancet points out that the principles of eugenics had wide currency at the time, not just in Germany, but in many other parts of the world. In fact, the Nazis’ sterilization law was partly based on legislation drafted by American eugenicist Harry Laughlin. Indeed, 12 US states including Indiana, Connecticut, Virginia, Oklahoma, and California, had forced sterilization laws on the books at some point in the early 20th Century.

The Nazis’ anti-Black racial policy led to the extralegal forced sterilization of an estimated 600-800 children born to White European mothers and African fathers who had served as soldiers during the French occupation of the Rhineland after WWI.

The Lancet authors estimate that in total, between 310,000 and 350,000 people were forcibly castrated or ovarectomized under the Nazi eugenics program. But sterilization was just the beginning.

In 1939, the Reich authorized Aktion T4, “a centrally organised patient mass murder programme.” Named forTiergartenstraße 4, the Berlin address where the program was headquartered, this policy mandated “mercy deaths” for people with disabilities, mental illnesses, or any other sort of incurable condition.

Physicians and midwives were mandated to provide the government with detailed information about all children with disabilities, who would subsequently be assessed by medical panels tasked with selecting which children could be “remediated” and which were to be killed. Under the Reich Committee for the Scientific Registration of Serious Hereditary and Congenital Diseases, the state established a network of 30 “special children’s wards” where children were given “good deaths” to free them from “lives not worth living.”

Between 1939 and 1945, an estimated 300,000 adult patients in psychiatric hospitals throughout Germany, Austria, occupied Poland, and other regions of Eastern Europe were culled and exterminated under Aktion T4. The infrastructure and methods for mass murder which defined the Holocaust —including the use of poison gas—were developed under Aktion T4.

And all of this was willingly overseen and implemented by medical personnel.

Willing Physicians

The Lancet authors point out that no civilian physicians were forced to participate in the T4 program, and that “many in the psychiatric elite advocated for the killing of patients deemed incurable, to enable specialists to focus on patients who could be healed and thus improve the reputation and influence of their profession.” Others who participated willingly were motivated by an ardent belief in Nazi ideology and racial hygiene theory.

One such enthusiastic participant was Hans Asperger, the Viennese pediatrician notable for his groundbreaking studies of atypical neurology in children, and for whom the Asperger Syndrome is named.

Asperger was a self-avowed “Austrofascist,” and Catholic eugenicist. During WWII he was one of many doctors who evaluated children according to their fitness or unfitness for integration into the German volk. Those he deemed unfit, he sent to the Am Spiegelgrund clinic (literally the “mirror-ground”), a T4 killing site in Vienna. During the war years, 789 children at Am Spiegelgrund were “euthanized” via gas poisoning, lethal injection, or deliberate starvation.

In addition to racial hygiene, there were also economic rationalizations for the state-sanctioned killings. By eliminating the “incurable,” hospital beds and medical resources would be made available for treating wounded soldiers, or Germans with treatable conditions.

Many victims of Aktion T4 were ethnic Germans, and by 1940, people within Germany—including the influential Catholic leader Archbishop Clemens August Graf von Galen –voiced opposition to the program. This prompted the regime to officially end it in 1941, at least on paper. In reality, the systems set in motion by Aktion T4 simply continued in the concentration camps that the Nazis built for extermination of Jews, Roma, gay people, political prisoners, and others.

The Lancet report notes that many medical personnel who ran T4 kill centers were reassigned to concentration camps. One example is Irmfried Eberl, an Austrian physician who ran two T4 “clinics,” and who was subsequently transferred in 1942 to the notorious Treblinka camp in Poland. In a period of 6 weeks, Eberl oversaw the murder of approximately 280,000 Jews. He was dismissed for failing to effectively conceal the realities of Treblinka from the neighboring villages.

Human Experiments

Beyond their role in justifying, systematizing, and facilitating mass murder, Nazi physicians and biomedical researchers also established a heinous program of experimentation on human subjects.

This, the Lancet commission points out, is especially ironic because at the turn of the 20th century, Germany was the first country to institute formal medical ethics guidelines for human research.

Back in 1900, the Prussian Ministry of Cultural Affairs issued a ruling against experimentation on humans without consent, in response to a scandalous experiment in which healthy women and children had been intentionally exposed to syphilis. It came three decades before the notorious Tuskegee study in which US Public Health Services researchers deliberately infected 400 African-American men with syphilis.

In 1931, the German Ministry of the Interior posted guidelines requiring that human subjects give explicit consent to participate in research, and only after appropriate instruction and education.

Though these rules were technically still in force under the Nazis, the new Reich interpreted them as applying only to members of the “German national body, but not to those excluded from it.” Enemies of the volk deemed “untermenschen” (literally, “under-men” or “subhuman”), were fair game for research.

Josef Mengele (center) was the most notorious perpetrator of medical atrocities during the Nazi period. As chief physician at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp complex, he routinely selected prisoners and new arrivals for extermination, and also conducted a series of medical experiments known for their extreme cruelty. He is flanked by Richard Baer (commandant of Auschwitz, May 1944 – Jan 1945), and Rudolf Höss (commandant of Auschwitz from May 1940 – Nov 1943). Image: US Holocaust Memorial Museum

The untermenschen—a term the Nazis applied to Jews, Roma, Slavs, Blacks, mixed-race people, homosexuals, people with disabilities, Communists, anti-Nazi dissidents, and prisoners of war–were human enough for any data obtained from them to be relevant to the German volk, but not human enough to be protected under guidelines limiting human experimentation.

Medical historian Paul Weindling and colleagues have carefully documented 300 human experiments involving at least 27,000 people, conducted by Nazi physicians and researchers during the war. These experiments covered a broad range of scientific questions. But they all aligned with core Nazi doctrines and goals: supporting the war effort, achieving German economic autarchy, eastward expansion of the Reich, and strengthening the health of the German race.

Research on concentration camp inmates included studies of physiology under extreme physiological stress like hypothermia or high altitude; control of infectious and insect-borne diseases; effects of chemical and biological weapons; human reproduction and mass sterilization; genetics and hereditary biology.

Josef Mengele is the most notorious Nazi physician. He oversaw the prisoner “selections” at Auschwitz-Birkenau, determining who was fit for forced labor and who was to be gassed immediately. He headed the “infirmary” in the camps, where he ran a number of experiments on prisoners.

Mengele was particularly interested in identical twin sets, using one twin as the experimental subject and the other as the control. Among his goals was to aid racially-superior couples to produce more twins thereby speeding the growth of the Aryan population.

He was also determined to develop blood tests that could reliably and irrefutably detect someone’s race. And he also ran disinfection and disease control studies which involved deliberately infecting prisoners in order to test experimental treatments.

“Mengele’s research practices were marked by extreme brutality and a complete disregard for the humanity of the people forced to participate, as well as the unscrupulous exploitation of the resources and atrocious context of the Auschwitz camp,” write the Lancet authors. The doctor was known as Todesangel (Angel of Death) for good reason.

“New Opportunities, Deregulated Spaces”

Mengele may have been extreme in his ruthlessness, but he was certainly not unique in his zeal.

“Medical scientists interested in pursuing research projects were generally aware of what they saw as new opportunities for research in the deregulated spaces created by the Nazi regime, where legal and ethical rules could be ignored,” writes the Lancet commission.

One example is Carl Clauberg, a gynecologist and fertility researcher who specifically requested permission from SS director, Heinrich Himmler, to set up a sterilization research project in Auschwitz. Similarly, SS physician Karl Gebhardt saw his assignment to Ravensbrück as an opportunity to test new sulfonamide drugs on prisoners of war deliberately inflicted with “standardized” wounds intended to simulate battle wounds.

The concentration camps were also a boon for anatomy labs at German universities. According to the Lancet report, academic centers now had easy access to human cadavers from the euthanasia programs, forced labor camps, and concentration camps.

A Catalog of Horrors

The 70-plus page Lancet report is a catalog of horrors difficult to fathom. Yet each statement in the report is referenced and well-substantiated. In aggregate, the evidence clearly shows “the cooperation between civil medical research institutions, military medicine within the German armed forces and SS, and the pharmaceutical industry.”

The report dispels several widely held, comforting notions that propagated widely throughout the medical world in the post-war era. One is that the medical atrocities carried out by the Nazis were the work of a small number of radical fanatics—the “a few bad apples” thesis.

Though there were many medical professionals who did resist the racist policies of the Reich, the Lancet report shows that the majority of physicians willingly participated.

“The historical evidence provided here will show that physicians joined the Nazi Party and its affiliated organisations in higher proportions than any other profession,” the authors note, adding that, “The convergence of professional interests with political motives partly explains the gravitation of many physicians towards Nazism: by 1945, 50–65% of German physicians had joined the Nazi Party, a much higher proportion than in any other academic profession.”

The Lancet authors also challenge the notion that the Nazis had no concept of medical ethics. In truth, all the horrors of the Holocaust occurred under a clearly articulated set of ethics crafted for the service of political, economic, and racial aims.

“Nazi Germany developed a specific form of ethics that put the health of the German people above all else, but that excluded vast numbers of individuals from being considered part of the German people according to eugenic, antisemitic, and other racist criteria. Thus, medical ethics became another instrument to help design, rationalise, and implement the regime’s eugenic and racist agenda.”

Within its own racist notions of public health, the Nazi medical establishment went to great lengths to promote the wellbeing of the Volk. The Reich established one of the world’s first public tobacco cessation campaigns, and it also actively promoted healthy whole-food diets. It ran prenatal health services and family support programs—but again, only for Germans deemed fit and worthy of them.

After the war, 23 Nazi medical personnel were brought to justice during the Nuremberg Doctors’ Trial of 1946-47, and 7 were sentenced to death. But the vast majority of those who perpetrated medical atrocities during the Nazi era—including Josef Mengele—were never captured or prosecuted.

The Lancet Commission on Medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust: Historical Evidence, Implications for Today, Teaching for Tomorrow is not an easy read. But it is an important one.

The authors effectively describe how the horrors of Nazi medicine emerged not from irrational rage, but from principles, ideologies, and worldviews prevalent throughout academia in 19th century Europe.

As much as it is a history lesson, the Lancet report is a cautionary tale.

The dangers of overly reductionistic thinking, medical industrialization, and co-optation of medical ethics by political agendas are with us today.

“In the Nazi era, science, medicine, and public health were used to justify and implement persecutory policies and eventually state-sanctioned mass murder and genocide. Studying the history of medicine during Nazism reveals the dangerous potentials of modern medicine, which coexist with medicine’s immense power to benefit humanity. The significance of this history is not limited to the descendants of the victims and perpetrators and their societies: it is relevant to communities worldwide—not least because early 20th-century Germany pioneered so many aspects of modern medicine that were adopted to varying degrees in many countries.”

END