Good medical practice is based on trust.

Patients trust that practitioners are knowledgeable, and that they use their knowledge intheir patients’ best interests. In turn, practitioners trust that researchers run their studies honestly, and that editors and peer-reviewers of the medical journals carefully scrutinize the papers they receive, sift out the garbage, and only publish studies that pass clinical, statistical, and ethical muster.

Research itself is also a trust proposition. From the lead investigators who design trials, and the Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) that approve them, to the research assistants and post-doctoral fellows who crunch the data, and the authors who write and submit the papers, there’s a thread of trust that depends on the right people doing the right things at each point along the path.

That’s how it ought to be in an ideal world. But the hard truth is, this is not an ideal world.

It’s an open secret that medical research fraud is rampant.

A recent article in The Guardian estimated that last year, there were more than 10,000 fraudulent papers retracted by journals across the sciences. That’s the highest number of retractions ever recorded. And this is likely just the surface layer of the problem.

Epidemic Proportions

Research fraud is widespread across all domains of science. As revealed in a Wall Street Journal article published on May 14, the proliferation of fraudulent papers prompted Wiley–one of the world’s oldest and most respected academic publishers –to shutter 19 of the journals under its recently acquired Hindawi imprint.

Wiley bought Hindawi, an Egyptian publisher of science journals in 2021, for $298 million. By May 2023, Wiley had to discontinue four titles–Computational and Mathematical Methods in Medicine, Journal of Healthcare Engineering, Journal of Environmental and Public Health, and Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience –because of the prevalence of bogus papers.

One year later, Wiley announced the discontinuation of 19 other titles, many though not all of which, are medical or healthcare-related. The company states that the closures reflect an effort to integrate Hindawi with Wiley’s existing journal portfolio, and to eliminate redundancies and journals that “no longer serve their communities.” But the Wall Street Journal claims that some of the journals on this list “were infected by large scale fraud.”

Over the past 2 years, Wiley has retraced more than 11,000 papers across journal holdings which represent hundreds of scientific disciplines. And Wiley is not alone. Other major academic publishers are also scrambling to deal with the rapid proliferation of fraudulent papers.

The problem of research fraud is especially prevalent in the field of nutrition, says Alan Gaby, MD, a holistic physician who is author of the massive textbook, Nutritional Medicine.

Now in its third edition, Gaby’s book contains nearly 17,000 research citations and covering the use of herbs and nutraceuticals for more than 400 specific health conditions. Suffice to say, Dr. Gaby has probably read more clinical research papers on nutrition than anyone on the planet.

He contends that the problem of research fraud has reached epidemic proportions.

“Over the past 50 years, I’ve probably reviewed about 50,000 papers. And about 15 years ago, I became aware of some irregularities in a lot of the research. A growing number of papers left me wondering if the research had actually been done at all, or if the data were simply fabricated.”

Fraudulent research corrodes public trust; it misleads clinicians; and it skews metanalyses. Once marketers and sales people get hold of it, they easily turn it into dishonest and misleading product claims. At minimum, ordinary people get ripped off. At the extreme, people could get hurt.

Gaby says the number of suspicious—or at least highly questionable–papers has surged dramatically in recent years, in part due to the growth of open access publishing and the proliferation of small, poorly refereed open-access journals and websites, some of which are pay-for-play operations.

But open-access is only part of the problem. Gaby says he’s seen numerous instances in which dubious nutrition studies have appeared in venerable, “high impact” (ie, widely-cited) conventional medical journals.

“Several hundred papers per year, in my view, raise questions about whether the research is legitimate.”

Gaby stressed that it is difficult—and time consuming—to prove definitively that a published paper is fraudulent. But there are an alarming number of studies that simply do not hold up to careful scrutiny. When this happens in respected peer-reviewed journals, as it sometimes does, it suggests that peer reviewers are failing to do their jobs, or that they’re turning a blind eye to shoddy work.

He published his concerns in an excellent 2022 article in Integrative Medicine: A Clinician’s Journal, and in lectures and webinars.

The “Sato Saga”

Dr. Gaby is not the only physician ringing alarm bells. Several years ago, a team of researchers based in New Zealand called out two prominent Japanese investigators—Yoshihiro Sato and Jun Iwamoto—claiming that nearly 300 of their published papers in 78 medical journals, had major methodological flaws, ethical lapses, and signs of fabrication.

Sato, who died in 2017, and Iwamoto were both prominent professors at Japanese universities. Their work was primarily focused on bone metabolism, and they published many studies looking at the effects of Vitamin D, Vitamin K, and folate. They also studied prescription drugs like methylprednisolone, hormone replacement therapy, and valproic acid. Some of their research extended into fields like neurology and gastroenterology.

Studies by Sato and Iwamoto have appeared in some of the world’s top journals, including the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), Neurology, and the Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism.

The saga began in 2006, when biochemist Alison Avenell, the Chair of Health Services Research at the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, was delving into the question of whether vitamin D could reduce bone fractures. While plumbing the literature, she came across two studies by Sato. One involved a cohort of stroke patients, and the other, patients with Parkinson’s.

Avenell noticed that in both studies, the patient populations had exactly the same mean body mass indexes. That, she thought, was statistically unlikely. She started digging more deeply, and the more she looked, the more anomalies she found: unreasonably large treatment effects, unusually large patient populations, plagiarized text, numbers that simply didn’t add up.

“Expressions of Concern”

Soon after, Avenell teamed up with Andrew Grey, Mark Bolland, and Greg Gamble of the University of Auckland, New Zealand. The team undertook an exhaustive review of 292 papers published by Sato alone or in partnership with Iwamoto.

In 2016, this intrepid team published an in-depth takedown of 33 studies by Sato, Iwamoto, or both. They notified 78 journals that most, if not all, of the nearly 300 papers published by these two researchers were flawed at best, fraudulent at worst.

The ensuing drama, well chronicled by the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s journal, Science, ultimately resulted in retractions of 121 studies, three corrections, and 12 “editorial expressions of concern”—that’s journal-speak for, “We question a study’s validity but don’t have a solid enough case to retract it.”

Not long before he died, Yoshihiro Sato admitted that he falsified research, and absolved Jun Iwamoto of any direct responsibility.

The so-called “Sato Affair” is one of the biggest legacies of medical research fraud in history. According to Retraction Watch, a website founded by former Medscape VP, Ivan Oransky and science writer Adam Marcus, that monitors retractions across a vast range of scientific disciplines, Sato and Iwamoto hold the 4th and 6th places for highest number of papers retracted worldwide.

Who’s number one? That dubious honor belongs to Joachim Boldt, a German anesthesiologist and ICU physician, who’s had a stunning 194 of his published papers retracted because of data fabrication and lack of ethics board approval.

Red Flags for Fraud Detection

With fraudulent research on the rise across the medical landscape, and peer review boards apparently faltering, practitioners need to sharpen their critical thinking skills when reading clinical studies. But one need not become a statistician.

“Several hundred papers per year, in my view, raise questions about whether the research is legitimate.”

–Alan Gaby, MD

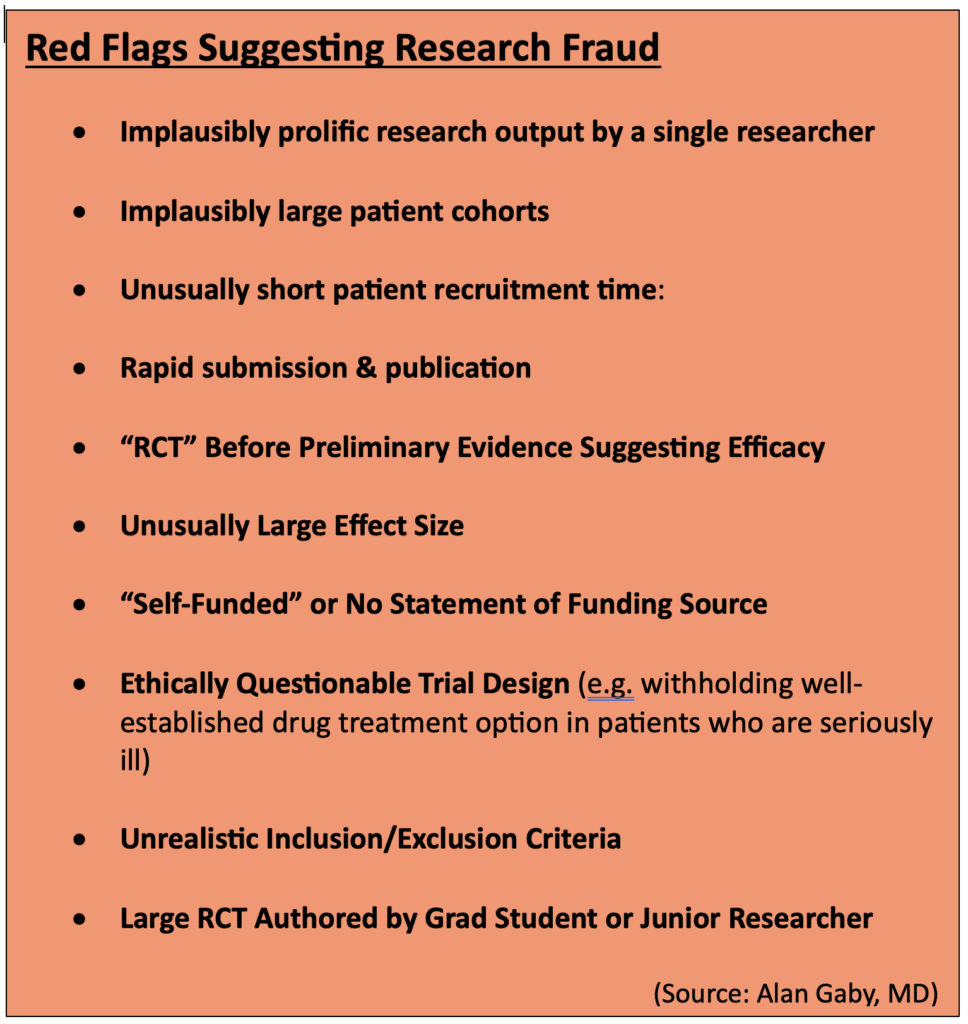

Over the years, Dr. Gaby has identified ten red-flag warning signs that raise the index of suspicion about misconduct or outright fraud:

- Implausibly prolific research output by a single researcher: A good clinical researcher typically completes and publishes 3-4 large, randomized, double-blind, controlled trials in a period of 5 or 10 years, Gaby says. Yet, some researchers publish 10, 20, or even 30 papers in that time span. “Whenever you see implausibly large research output, it makes you wonder how could they have possibly done all of that research.”

- Implausibly large patient cohorts: Gaby says that over time, people who read a lot of studies develop a good sense of how many people could be reasonably enrolled in a given trial. This is based in part on the number of researchers and clinics involved, the size of those clinics, their catchment areas, the general prevalence of the disease in question, and the stringency of inclusion/exclusion criteria. In some nutrition studies, a lone researcher claims to have a trial population far larger than one could reasonably expect even in a multi-center study, let alone a trial at a single clinic.

- Unusually short recruitment time: Recruiting patients for legitimate clinical studies is not easy, nor is it swift. It takes a lot of outreach, effort, and resources. If a study claims to have recruited hundreds of people with a particular disorder in a 3-month period, and they all met strict inclusion criteria, you should be suspicious.

- Rapid submission & publication: Most studies disclose the time period for patient recruitment, and the duration of treatment lasted. From that, you can estimate the earliest possible date of completion. Gaby says he sometimes sees studies in the nutritional literature that were submitted for publication very soon after it would be possible to complete the trial, based on the schedule described in the text.

“In some cases, we’ve seen papers that were submitted before it was possible to have completed the trial. In many other cases, only a few weeks to a month after the trial could have been completed. That’s also implausible, because in a real study, it takes a very long time to analyze data, to write the paper, and then to submit it.”

- An RCT before there is preliminary evidence of efficacy: Real clinical trials are costly. Few funding sources are likely to underwrite that cost without some compelling preliminary evidence from case reports, open-label uncontrolled trials, or pilot studies showing that the intervention in question might be beneficial. Yet, in the nutrition and botanical literature, there are many alleged RCTs done without such preliminary evidence.

- Effect sizes larger than one would expect from nutrients: “If you read a lot of medical literature, you start to get a general idea of how effective nutrients are. Sometimes it’s dramatic, but most of the time it’s not. Usually, it’s a combination of nutrients producing a moderate effect,” says Gaby. Yet, “in many of the studies I’ve looked at, there were much larger effects…effect sizes you usually only get from drugs. So that raises eyebrows.”

- No funding source is listed, or the study is “self-funded”: This is particularly important when researchers describe their studies as RCTs. Real RCTs are very expensive. If nobody is funding it, one has to wonder how the study was possible. And if funding sources are not openly stated, one needs to wonder why.

- The trial design raises ethical issues: If a study involves patients with serious, advanced disease, and they’re randomized to either a nutrient or a placebo, there’s likely an ethical problem. That’s because clinical research is still in the domain of patient care, and doctors have a responsibility to treat people with the best available therapies. Whether natural medicine advocates like it or not, the “best available” treatments for serious diseases are usually prescription drugs. If researchers intentionally withhold a viable drug option in order to test a nutrient against a placebo, they’re treading on shaky ethical ground.

- Implausible patient characteristics: Pay close attention to the stated inclusion and exclusion criteria, especially the age range and baseline characteristics. Dr. Gaby says he sometimes sees papers that indicate a particular age range for inclusion, but the when he looks at the mean ages and the standard deviations in the results, it would be mathematically impossible that all participants actually met the stated age criteria.

- A large study—especially an RCT—authored by a grad student. Grad students are the unsung heroes of clinical research. While they certainly deserve credit for their efforts, the reality of academic hierarchies is that they are seldom lead investigators, especially on big trials. Yet in the nutrition literature, one will often see big studies authored by a grad student or junior researcher, sometimes as the sole investigator. While this is not a universally damning indicator, it should raise the index of suspicion a bit, especially if there are other red flags.

Countries of Origin

Dr. Gaby says there’s another important indicator of potential scientific fraud: geography.

“The most common country of origin, by far, for questionable papers, is Iran. To a lesser extent, Egypt and China. Then India, Pakistan, Japan, and Italy.”

Though a German holds first place for total retractions, and other Japanese researchers aside from Sato and Iwamoto also rank high on Retraction Watch, Iran is now the world’s leader in terms of the sheer volume of questionable papers flooding the literature, says Gaby.

“It’s gotten to the point that if something comes out of Iran, I’m inclined to not bother even reading it. Which is too bad, because probably some of the studies are legitimate. But my estimate is that at least three-quarters and probably more of the studies coming out from Iran these days, and to a lesser extent from Egypt, Japan, Italy, and others, raise serious concerns about whether the studies were actually done.”

Iran has an advanced healthcare system—a mix of public, private, and non-governmental non-profit payers. On some public health metrics, it ranks higher than the US. Roughly 90% of all Iranian citizens there have some form of healthcare insurance.

Unfortunately, the country also has a highly competitive market for well-paying, high-prestige jobs that require advanced degrees and scientific prominence. That, along with a totally unregulated cottage industry of for-hire study writers, is a major driver of fraudulent research from Iran.

“The most common country of origin, by far, for questionable papers, is Iran. To a lesser extent, Egypt and China. Then India, Pakistan, Japan, and Italy.”

–Alan Gaby, MD

The problem is not new. In 2016, Richard Stone the International News Editor for Science magazine authored an article called, “In Iran, a Shady Market for Papers Flourishes.” In it, he reveals a lucrative business centered on fabricating research and getting it placed in the international literature.

For the equivalent of around $600 (1.8M Iranian Tomans), scientific aspirants can commission a paper or thesis that ‘doesn’t need lab work.” An additional $400 increases the odds that the paper will be published “under your own name” in a “reputable” journal. That means, a journal published by an internationally recognized publisher like Springer or Elsevier.

“Paper Mills”

Stone says there are several thousand of these ‘paper mills’ throughout Iran, mostly centered around prominent academic institutions. He cites a prominent member of Iran’s Academy of Sciences who, in 2014, estimated that roughly 10% of all masters and PhD theses awarded in the country –amounting to about 5,000 theses per year—are based on research that the candidates never did.

This is completely legal. There are no laws in Iran—or other countries for that matter–against fabricating scientific data or publishing bogus research. Stone notes that in 2016, a group of Iranian scientists concerned about scientific integrity proposed a law to criminalize—at least partially—the selling of concocted science. It never saw the light of day.

In his review in Integrative Medicine, and in his lectures, Dr. Gaby draws attention to several Iranian researchers who published prolifically on nutritional topics, and whose work is very likely fraudulent.

Asemi’s Astonishing Output

Among them, Zatollah Asemi, a metabolic disease specialist at the Kashan University, who published more than 191 “RCTs” over his career, including 148 studies published between Jan 2016 and March 2019.

“That’s almost 50 papers per year,” says Gaby. “Just on face value, that level of productivity should raise a red flag.”

Further, Asemi’s output indicates that he was simultaneously running as many as five RCTs looking at five different treatments, concurrently. “That is unprecented. In my decades of reviewing scientific papers, I’ve never come across anyone as remotely prolific as this.”

Asemi’s numerous citations cover nutrients and herbs including quercetin, ginger, probiotics, magnesium, zinc, Vitamin D, berberine, and melatonin. He and his colleagues claim they’ve used these to treat an equally wide range of disorders including metabolic syndrome, diabetes, depression, leukemia, osteosarcoma, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Papers by Asemi and colleagues have found their way not only to obscure open-access journals, but into some well-reputed high-impact ones like the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, the Canadian Journal of Diabetes, and the British Journal of Nutrition.

Gaby says the alarm bells about Asemi’s research are loud and numerous.

Beyond the implausibly prolific output, nearly all of his 191 trials show unequivocally positive, “statistically significant” outcomes for the interventions being tested. Often the effect sizes are large—larger than one usually sees in legit nutrient studies.

Further, Asemi’s trials often have implausible time lines. “At least 12 of his papers were submitted to journals before it was possible to have completed the trials. That’s easy to determine because he says exactly when he started them, and how long they lasted.”

For example, a 2018 study of magnesium and zinc for women with PCOS, published in the journal Biological Trace Elements Research, states that recruitment was from June to August 2017, and that the treatment period was 12 weeks. If recruitment ended on August 1 2017, the earliest that a 12-week trial could have been completed would be October 24 2017. Yet the journal received the paper on Sept 27 2017—weeks before the treatment protocols could be completed.

Another of Asemi’s studies—this one looking at the effect of multi-mineral plus vitamin D supplementation in women with gestational diabetes— claims to have recruited 60 women with this condition, who were between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation, at a single clinic, within a 3 week period. Dr. Gaby says this is highly unlikely.

“I looked up some data to see if that was even possible. The region where this study was conducted (a city called Arak), has a population of about 500,000. And I looked up the prevalence of gestational diabetes, and the birth rates for this area. What I calculated was that during any given 3-week period, only about 36 women in the entire city would have had gestational diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation. Yet Asemi claimed to have recruited 60 such women at just one clinic.”

Reluctance to Retract

Gaby shared his concerns about Asemi with the New Zealand team that ultimately took down Sato and Iwamoto. The group obtained a grant to undertake an exhaustive review of 172 studies by Asemi and colleagues. The result? A comprehensive 115-page dossier which the Auckland group sent to editors at 65 journals. It details the myriad inaccuracies, implausibilities, discrepancies, and ethical breaches spanning Asemi’s career.

Progress has been slow, but as of now 12 of Asemi’s papers have been retracted, and editors have issued 85 Expressions of Concern.

Gaby says there are dozens of other Iranian researchers whose work is just as questionable. There’s Reza Safarinejad, an internationally known urologist, whose main interest is male infertility. He’s published numerous studies on the impact of coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinol) on semen parameters, sperm function, and pregnancy rates. He’s also published on omega-3s, selenium, and N-acetyl cysteine for male fertility. According to Gaby, nearly all of Safarinejad’s studies are problematic.

He points to one in particular: a 2009 paper in the Journal of Urology looking at the effect of CoQ10 on sperm parameters and hormone levels in 212 infertile men.

Safarinejad is the only author of this paper, and claims to be the sole treating physician. Gaby holds that 212 is an implausibly large cohort for a stand-alone urology practice doing its own non-funded research (no funding source is listed). “A single investigator does not have the time or resources to conduct such a large trial by himself.”

The protocol was equally implausible: It claims that all 212 men visited the clinic 12 times over a period of 13 months, and gave two semen samples at baseline, and two samples within a 1-2 week period around each visit. Further, the semen was collected after 3 days of recommended abstinence.

Implausible Protocols

“That’s 24 semen samples per subject, with a total of at least 72 days of abstinence over a 13-month period. I don’t know anybody who would do that. If somebody is infertile and wants to have a pregnancy, he’s going to want to have intercourse and have a baby. The idea that anyone would sign up for this (protocol) is crazy,” says Gaby.

There are also big logistical questions, like the process for collecting the samples. “While half the 24 semen samples could potentially have been collected during the 12 clinic visits, the other half (12 samples) would have to be collected between visits. That is, at home. The subjects would have to deliver the samples to the clinic within 1 hour of ejaculation, because sperm cells start to die off after an hour. So, they would have to get to the clinic within one hour, on 12 different occasions. The paper claims 194 of the 212 men completed the trial and provided all the required 24 samples. That defies belief.”

Safarinejad claimed that he and a lab tech did all the semen analyses. Doing the math, that’s 4,650 sets of lab tests, all of which had to be done within hours of ejaculation. That’s a heavy workload even for someone not running a busy clinic.

Further, the study’s inclusion criteria states that men were eligible to participate only if they had “normal” fertile female partners “according to investigation.” That meant the women had undergone a complete medical history, physical exam, lab testing, and hysterosalpingogram.

“Doing this on 212 women would be very expensive and time-consuming. It is not something a urologist would do, so it would be done by a gynecologist. But the paper does not specify who conducted these fertility evaluations and who paid for them. And since Safarinejad is the sole author, and there’s no indication of funding source, it defies the imagination that 212 women would have had salpingograms just so their husbands could participate in a study.”

Dr. Gaby sent a letter to the editors of the Journal of Urology detailing his concerns. “They wrote back by email within 3 hours saying they were going to investigate this. It took about 6 months, but a couple months ago they issued an Expression of Concern about all 14 papers that Safarinejad had published in their journal.” It’s slow progress, but this is several steps in the right direction.

The examples cited above are but a few. Gaby says he’s identified many more problematic studies from Iran and from other countries. And keep in mind that the US is definitely not immune to bad research.

Corrosion of Trust

Fraudulent research corrodes public trust in science; it misleads clinicians; and it skews metanalyses and systematic reviews. Once marketers and sales people get hold of it, they easily turn dodgy data into dishonest and misleading product claims. At minimum, that means ordinary people get ripped off. At the extreme, people could get hurt.

There’s no lack of dubious research on pharmaceuticals, but the problem is especially damaging to the field of natural medicine which is continually fighting for credibility in the eyes of the broader medical community, the public, and the regulators. Fraudulent studies like those described in this article bolster the critics who want to paint the entire supplement industry as dishonest and maleficent.

As is easily seen from Dr. Gaby’s experience, and the New Zealand group’s efforts, medical journals are reluctant to retract studies once they’re published. People don’t like to admit they’re wrong, and retractions make journals—and their editors—look bad. Plus, there could be potential accusations of libel, even lawsuits.

Even if papers are retracted, their negative impact lingers, especially if they’d been in the literature for a long time, they appeared in high-impact journals, and they were included in metanalyses.

Despite his extensive experience exposing fraudulent research, Dr. Gaby stresses that most nutrition/supplement researchers are honest, and most studies are clean.

“Most nutrition research is believable, and the incidents of fraud do not change my observation that nutritional medicine is highly beneficial for prevention and treatment of a wide range of health conditions. But this is a stain on scientific integrity.”

END