One in every two people with irritable bowel disease (IBD) is zinc-deficient, according to a recent systematic review of nine studies representing more than 2,400 IBD patients.

The prevalence of zinc deficiency, based on serum zinc measurements, was higher among those with Crohn’s disease (CD), affecting 54% of the patients in this subgroup, versus 41% of those with ulcerative colitis (UC).

“This is the first meta-analytic study to be conducted on the prevalence of zinc deficiency in IBD,” wrote lead author Roberta Zupo, at the Saverio de Bellis National Institute of Gastroenterology, Castellana Grotte, Italy. “The present research highlights the importance of considering zinc as a micronutrient to be monitored, because every second IBD patient shows a deficiency.”

The data were published in the journal Nutrients, last October.

High Prevalence

Zupo and colleagues screened 152 studies that included data on nutrient deficiencies in IBD patients. Only nine trials had sufficient data on zinc, and met the researchers’ strict inclusion criteria. The nine studies analyzed were all published between 2017 and 2022.

The studies represented populations from Asia, Europe, and the US. A total of 1,677 of the 2,413 pooled IBD patients (69.5%) had CD, while 736 had UC.

There were some differences across the nine studies regarding the threshold used to define “deficiency.” Some investigators used a cut-off of 70 μg/dL, while others defined deficiency as serum values under 10.7 μmol/L. The largest of the trials—a 996 patient study published by Shivi Siva and colleagues at the University of Chicago in 2017, used a threshold of 0.66 mg/mL.

But overall there was little heterogeneity between the studies they analyzed, and the risk of bias was low, according to Zupo.

“Zinc deficiency may predispose to growth retardation in young populations, and to loss of appetite, impaired immune function, and structural impairment of the intestinal endothelium. In severe cases, it may also drive hair loss, diarrhea, delayed sexual maturation, impotence, hypogonadism in males, and eye and skin lesions.”

Roberta Zupo, Saverio de Bellis National Institute of Gastroenterology, Castellana Grotte, Italy

Taking the 2,413 pooled patients as a group, the overall prevalence of zinc deficiency was exactly 50%, though this number ranged from roughly 21% to over 60% across the nine studies. That 50% figure is substantially higher than the 15% prevalence reported in an earlier, smaller study of this subject (Vagianos K, et al. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2007).

With two exceptions, most of the studies under review showed a pattern of higher prevalence of zinc deficiency among the subjects with CD compared with those who had UC. Again, there were variations between the studies in terms of the number of CD patients who showed zinc deficiency. Two studies reporting numbers over 80% in this subgroup.

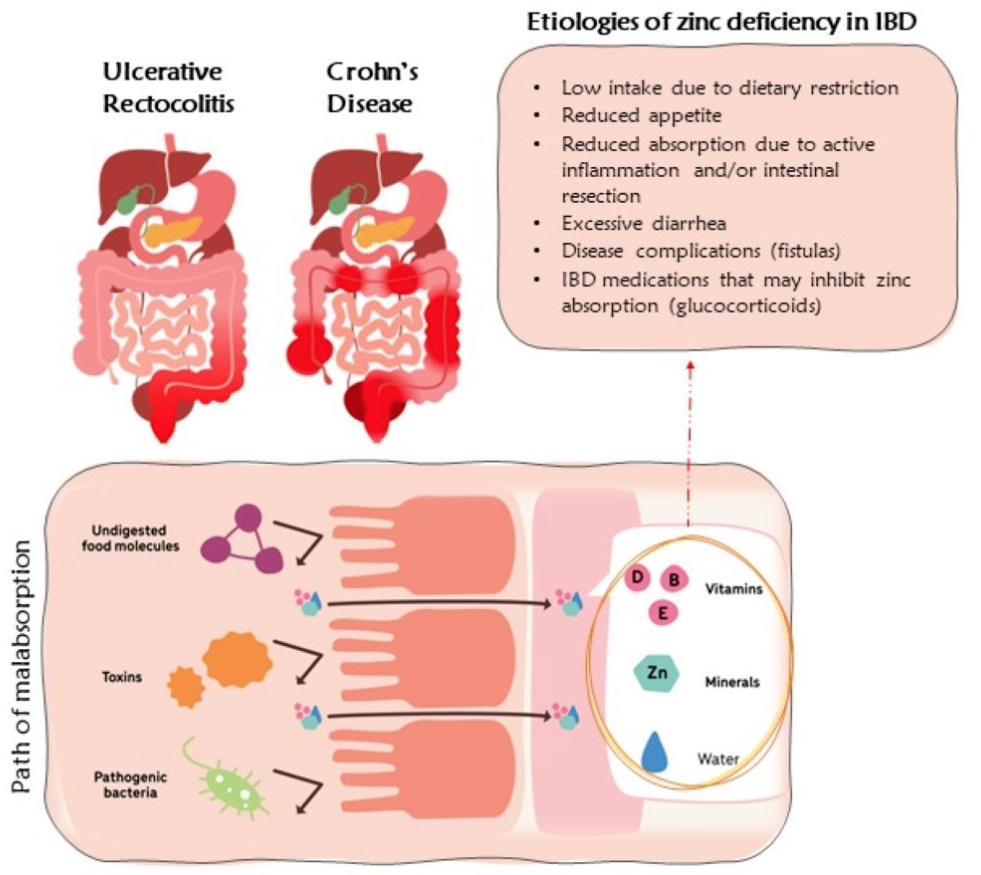

Zupo and colleagues believe the higher prevalence among CD versus UC patients makes sense given what is known about the process of dietary zinc absorption.

This trace mineral is primarily absorbed in the distal duodenum and proximal jejunum. CD can affect any part of the GI tract, including the stomach, duodenum, and small intestines, whereas UC typically affects only the colon and the rectum. Consequently, CD is more likely than UC to affect the areas of the gut mucosa involved in zinc absorption.

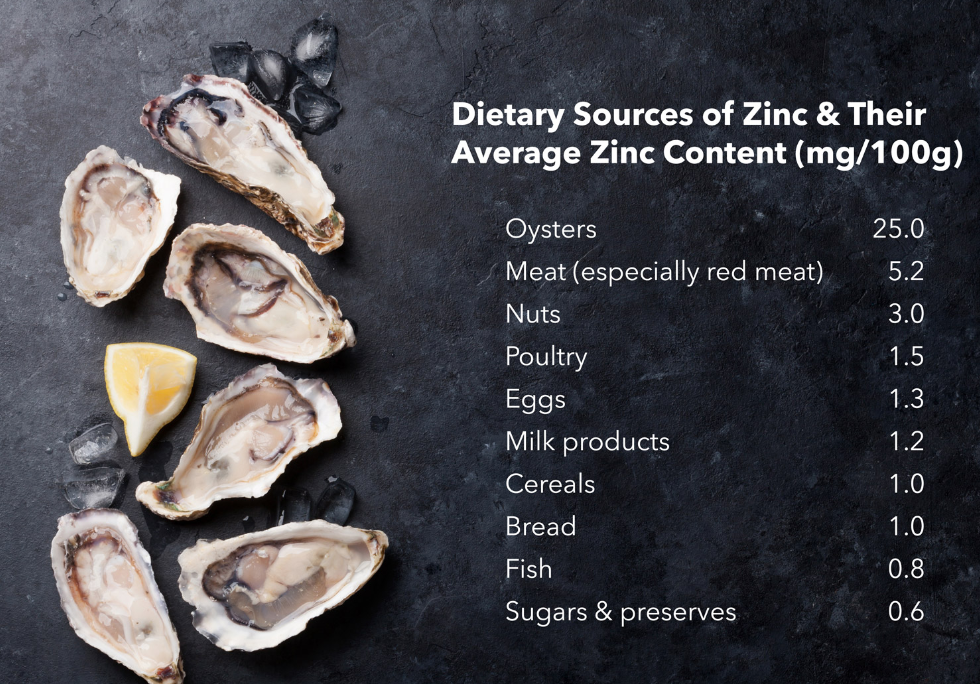

The authors suggest that the zinc deficiencies observed in patients with IBD reflect a combination of malabsorption intrinsic to this disease, and also to low consumption of zinc-rich foods such as beans, nuts, shellfish (especially oysters), whole grains, and dairy. Loss of zinc due to diarrhea, high-exit fistulas, and ostomies—all of which are common in the context of IBD—also play a role.

A Pattern of Malabsorption

The high prevalence of zinc deficiency fits an overall pattern of nutrient deficiency, and even malnutrition, in IBD patients.

According to a recent study by Stephanie Gold and colleagues at the Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Medical Center, New York, NY, 36% of a cohort of 182 recently diagnosed IBD patients met criteria for malnutrition. The vast majority (78%) had at least one micronutrient deficiency. Those with active Crohn’s were 2.8 times more likely to be malnourished (Gold SL, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022).

Chiara Vigano and her team at the San Gerardo Hospital, Monza, analyzed data from 295 adults with IBD (50% CD, 50% UC) at 11 hospitals in the Lombardy region of Italy.

They found that 23% of the patients had at least one significant micronutrient deficiency, with deficiencies in B12, folate, and ferritin being among the most prevalent.

Vigano and colleagues did not see any statistically significant differences between the CD and UC patients in terms of disease-related malnutrition. However, they did see correlations between disease-associated malnutrition and higher median levels of C-reactive protein. This suggests a relationship between poor nutritional status and increased inflammation, though from the perspective of causality the direction of this relationship is not clear.

They presented their data as a poster at the 2022 United European Gastroenterology Week conference in Vienna last October.

Deficiencies of zinc and other trace elements are major contributors to the symptom burden of IBD, and to the adverse impact of this disease on patients’ quality of life.

A recent study by researchers at the National Institute of Medical Science and Nutrition in Mexico City indicates that vitamin D deficiency is also common among IBD patients.

Andrea Sarmiento-Aguilar and colleagues reviewed medical records from 270 IBD patients (83% UC, 17% CD), 225 of whom had vitamin D measurements included in their charts. Of this group, 48% were vitamin D insufficient, defined by serum levels between 21-29 ng/mL. An additional 34% were frankly deficient, based on a cutoff of 20 ng/mL.

Major Impact on QOL

Dr. Zupo and her colleagues hold that deficiencies of zinc and other trace elements are major contributors to the symptom burden of IBD, and to the adverse impact of this disease on patients’ quality of life.

A key component for the proper functioning of many enzymes and transcription factors, zinc is also important for regulating immune system responses, cell cycling, and apoptosis.

“Zinc deficiency may predispose to growth retardation in young populations, and to loss of appetite, impaired immune function, and structural impairment of the intestinal endothelium. In severe cases, it may also drive hair loss, diarrhea, delayed sexual maturation, impotence, hypogonadism in males, and eye and skin lesions,” says Zupo.

“All these aspects highlight the importance of early nutritional preventive management in IBD settings, from better quality of life and healthcare burden perspectives.”

She and her colleagues consider the relationship between zinc deficiency and IBD to be bidirectional, since low serum zinc levels tend to exacerbate inflammation and damage to the GI mucosa, and mucosal damage impedes absorption of zinc and many other nutrients.

A Role for Supplementation?

The big question is whether zinc supplementation or intentionally increasing the intake of zinc-rich foods can raise serum zinc levels in IBD patients and mitigate the symptom burden.

That question is largely still unanswered, although there are a few studies suggesting that supplementation may be beneficial.

In 2001, Sturniolo and colleagues published a non-controlled study of 12 patients with quiescent CD but who showed increased intestinal permeability based on measurements of lactulose/mannitol ratios. Following eight weeks of supplementation with zinc sulfate (110 mg thrice daily), the mean lactulose/mannitol ratios were significantly lower, and 10 of the 12 patients were above the cutoff for “normal” permeability (Sturniolo GC, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2001).

In other words, zinc supplementation seemed to tighten the loose and permeable epithelial junctions.

Various researchers have proposed doses ranging from 40 mg/day for 10 days to up to 110 mg per day for 8 weeks in the IBD population.

Commenting on the Sturniolo paper, Zupo and colleagues note that, “This latter finding is critical because intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction may allow leukocytes to pass through, causing exposure to a “storm” of luminal antigens, a hallmark of IBD activity.”

In their 993-patient study, Siva and her team reported on a subset of 232 CD patients who were zinc-deficient at baseline, but who were able to normalize their serum zinc levels via supplementation or dietary changes over a period of 12 months. Compared with those who remained zinc-deficient, the 76 patients who were able to raise their zinc levels into the normal range (above 0.66 mcg/ml) had fewer hospitalizations, fewer surgeries, and fewer CD-related complications. The differences were statistically significant.

The University of Chicago researchers observed a similar pattern among their 174 UC patients, although in this subgroup normalization of zinc levels did not result in a significant decrease in subsequent surgeries (Siva S, et al. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017).

These data are promising, but they need to be corroborated by prospective supplementation trials.

In their 2017 review on the subject of nutrient deficiencies in IBD patients, Fayez Ghishan and Pawel Kiela at the University of Arizona’s department of pediatrics, note that IBD-associated diarrhea is a strong indication for zinc supplementation (Ghishan FK, Kiela PR. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2017).

They, and other authors, have suggested that the current RDAs for zinc—11mg/day for adult males, and 8 mg/day for females—may be too low for zinc-deficient IBD patients. Various researchers have proposed doses ranging from 40 mg/day for 10 days to up to 110 mg per day for 8 weeks in the IBD population.

But Ghishan and Kiela urge caution when pushing the doses. They point out that the upper limit for avoidance of potential toxicity is 40 mg/day. Beyond that, there’s a risk that zinc will interfere with absorption of iron and copper. On the other hand, it is important to be aware that increased intake of calcium or folate can impair absorption of zinc.

Also keep in mind that citric acid may improve zinc absorption, whereas iron, copper, dietary fiber, and phytates found in many types of legumes and seeds, may inhibit absorption.

Based on studies of patients with cystic fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis, or other conditions that tend to cause micronutrient malabsorption, Zupo and colleagues propose that daily zinc intake in the range of 30–40 mg daily, is reasonable in IBD patients.

END