Vitamin B12 deficiency is more common than many people realize. Large epidemiological surveys suggest that roughly 6% of all US adults under age 60 years are deficient, with the number rising to about 20% in people over age 60. Some estimates put the prevalence as high as 25%.

Those are certainly big numbers, but recent research suggests that our estimates may be way off, and that the actual prevalence might be significantly higher. There are many fallibilities and inconsistencies in the way we test for B12 deficiency, and consequently, we may be missing a lot of cases.

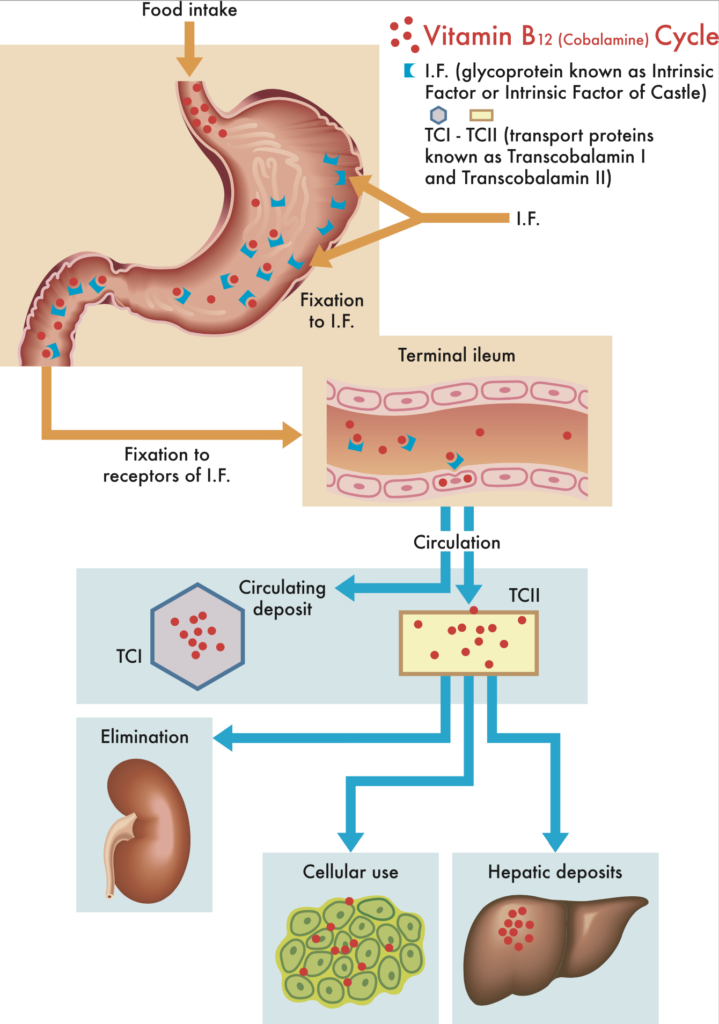

To understand how vitamin B12 levels are evaluated and why standard tests fall short, we must first understand how vitamin B12 is absorbed and utilized.

The Journey of Vitamin B12

To be appropriately broken down and used by cells, vitamin B12 (aka cobalamin) in food undergoes a somewhat complex multi-step process:

- Vitamin B12 is highly acid-sensitive. In order to pass through the acidic environment of the stomach, it must be bound and protected by a protein known as haptocorrin (also called transcobalamin-1). The haptocorrin-B12 is impervious to stomach acid, enabling the vitamin to pass through the stomach and into the duodenum and small intestine.

- Once in the small intestine, the B12 is then severed from haptocorrin by pancreatic enzymes.

- After this bond is severed, the free B12 is then bound by a different compound known as intrinsic factor, which renders it absorbable. It is curious that intrinsic factor is secreted by the gastric parietal cells—the very same cells that secrete HCl in the stomach.

- Intrinsic factor is required for proper absorption of vitamin B12, which takes place in the terminal ileum.

- Once absorbed into the bloodstream, B12 is then bound to transport proteins called transcobalamins I and II,

- These transport proteins deliver vitamin B12 to the tissues for immediate use, as well as to the liver where the excess B12 can be stored.

Problems with Standard Tests

In conventional medicine, the “gold standard” test for diagnosing a B12 deficiency is to measure plasma B12 levels. The basic method is as follows:

- A blood sample is saturated with predetermined levels of vitamin B12 in a process known as a competitive binding luminescence assay.

- The B12 introduced into the sample binds to the intrinsic factor – the protein necessary for proper absorption of vitamin B12.

- From there, the blood sample is analyzed to measure the amount of unbound intrinsic factor and vitamin B12. This unbound B12 is the plasma level we see on the lab report.

Lab values vary slightly, but generally speaking any measurement under 200 pg/mL is considered to be an indicator of B12 deficiency.

This standard approach can certainly detect some cases of vitamin B12 deficiency, but there is a major gap in the capabilities of the test, and it can lead to inaccurate and even entirely false readouts (Iltar U, et al. Blood Res. 2019). In some cases, it gives a false normal reading or even a false B12 elevation (Scarpa E, et al. Blood Transf. 2013).

If you suspect a patient has a vitamin B12 deficiency, order a full laboratory workup that includes the standard B12 measurement, but goes well beyond it.

There are two main reasons the standard method may not be able to give us an accurate snapshot of vitamin B12 levels:

- Intrinsic factor antibodies: In some cases, the patient’s immune system is producing antibodies specific to intrinsic factor. These antibodies may bind to the intrinsic factor test reagent, thus interfering with the test readout and subsequently delivering a false normal or false high measurement.

- Functional B12 deficiency: In other cases, a patient may indeed have adequate levels of B12 floating around in the blood, but the tissues may not be able to properly utilize it. The plasma B12 level alone doesn’t always give us a clear picture of whether or not someone’s body is able to appropriately utilize the B12 that’s available.

These variables mean that we cannot assume that a “normal” level on a standard B12 test categorically rules out deficiency, especially if a patient’s symptom pattern is strongly suggestive of deficiency.

A deficiency in vitamin B12 can lead to a wide variety of symptoms and consequences ranging from unpleasant to quite serious. They include:

- Fatigue, brain fog, and muscle weakness

- Digestive issues and intestinal problems

- Nerve damage and neurological changes manifesting as numbness or tingling in the hands and feet

- Mood disturbances, especially depression and anxiety

- Increased risk of neurodegeneration which can predispose to dementia

- Increased risk of cardiovascular disease and stroke

- Anemia and/or megaloblastic anemia (large, abnormally nucleated red blood cells that don’t function properly)

- Low white blood cell counts and/or low platelet levels

- Weight loss

- Infertility

- Disturbances in fetal development like neural tube defects, developmental delays, and failure to thrive

Who’s at Risk?

Our bodies are unable to produce vitamin B on their own – meaning we must obtain all of our vitamin B12 from the foods we ingest. Functionally, someone’s B12 status depends on what the person eats, the digestive health status, and the ability to absorb and utilize the vitamin. Risk factors for deficiency include:

- Impaired absorption or digestive diseases such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, bacterial overgrowth, leaky gut syndrome

- Hypochlorhidria (inadequate stomach acid production)

- Bariatric surgery or history of other surgeries on digestive organs

- Immune system conditions like Graves’ disease, lupus, or any other form of autoimmunity

- Drugs that impair B12 absorption, such as many of the acid-suppressing drugs prescribed for heartburn or ulcers, or the diabetes drug Metformin

- Heavy and frequent alcohol consumption

- Strict vegan or vegetarian diet (since most B12-rich foods like eggs, meat, and dairy, are from animal sources)

- Age over 60

The factors listed above certainly can put someone at increased risk of vitamin B12 deficiency. But researchers are finding that B12 deficiency may be much more prevalent than previously believed – even in those with no clear risk factors.

A patient may indeed have adequate levels of B12 floating around in the blood, but the tissues may not be able to properly utilize it. The plasma B12 level alone doesn’t always give us a clear picture of whether or not someone’s body is able to appropriately utilize the B12 that’s available.

If you suspect a patient has a vitamin B12 deficiency, order a full laboratory workup that includes the standard B12 measurement, but goes well beyond it. I’ve compiled a list of 15 Essential Lab Tests Everyone Should Consider by Age 30. Combined, these data will give a much more accurate picture of what’s actually going on.

- Complete Metabolic Profile (CMP), including measures of albumin, bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen, calcium, creatinine, electrolytes (sodium, potassium, bicarbonate, and chloride), glucose, liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine transaminase (ALT), and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)), and total serum protein levels.

- Complete Blood Count with Differential (CBC)

- Advanced Lipid Panel, including ApoB and Lp(a): Beyond the basic lipid measures like total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, and triglycerides, it’s also important to assess apolipoprotein B (apoB) and lipoprotein(a) or Lp(a) levels, both of which have strong bearing on cardiac health.As they say – the devil is in the details!

- Inflammatory Markers, including High-Sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), Homocysteine, Lipoprotein-Associated Phospholipase A2/PLAC, Myeloperoxidase (MPO), Oxidized LDL, and Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). Elevated inflammatory markers can be a huge indicator of something brewing beneath the surface, which can clue us into the need to dive deeper into identifying the source of inflammation.

- Heavy Metal Testing, including aluminum, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, lead and mercury. Heavy metals exert their toxic effects very slowly. Over time, they can wreak havoc on health.

- Complete Thyroid Panel, including Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), Free thyroxine (T4) and free triiodothyronine (T3), Thyroid peroxidase antibodies (TPO), Thyroglobulin antibodies (TgAb), and Reverse T3. Since the cascade of thyroid hormones affects just about every cell in the body, and regulates many aspects of metabolism and energy production, it is essential to get a complete picture of a patient’s thyroid function.

- Complete Hormone Panel: Again, because hormones are central to regulation of physiological function, it is important to get a comprehensive picture of what’s going on—especially in someone who experiences a lack of energy (one of the symptoms of B12 deficiency). You’ll certainly want to assess sex hormones (estrogen, testosterone, progesterone, and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG)). And I highly recommend evaluating cortisol levels with a 4-point cortisol test which tracks how the levels fluctuate throughout the day.

- Autoimmune Markers: Since B12 deficiency is often associated with autoimmune conditions, it is important to measure things like anti-nuclear antibody (ANA), and to get a full panel of extractable nuclear antigens.

- Immunoglobulin Levels, including IgM, IgG, IgA, and IgE. Together, the levels of these different immunoglobulins can give us a glimpse into how well (or how not-so-well) someone’s immune system is functioning, and clue us about previously undetected, underlying, sub-clinical infections.

- Fasting Glucose, Insulin, Hemoglobin, A1C, and Uric Acid: These four variables are inter-related. The higher they are, the less efficiently the body is able to properly process and utilize sugar. Elevated glucose, insulin, and A1C plus elevated uric acid predispose to conditions like gout and kidney stones. Testing all of these factors provides insight on glucose metabolism, and give us an edge in combating metabolic disorders like insulin resistance, diabetes, and obesity.

- Serum Vitamin D: Given this vitamin’s myriad roles in immune function, nutrient absorption, bone health, and mood regulation, it’s important to know each patient’s vitamin D status, and to supplement appropriately when someone is deficient.

- Micronutrient Testing: If someone is B12-deficient, or showing signs of deficiency, odds are good that there are other vitamin, mineral, and antioxidant deficiencies as well. Testing for specific micronutrient deficiencies can help you more precisely and accurately address them.

- Markers for Celiac & Gluten Sensitivity: Since celiac disease puts people at risk for B12 deficiency, it is important to rule it out. It’s also a good idea to assess a patient’s sensitivity to gluten, since many people have sensitivities that can affect their overall nutritional status.

- Fatty Acid Testing: Lack of omega-3s in the diet predisposes people to inflammatory conditions, especially if there’s a concomitant excess of omega-6 fatty acids. I recommend checking: Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), Docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), Linoleic acid (LA), and Arachidonic acid (AA).

- Iron Study: Iron can be tricky. Deficiency and overload are both problematic. A simple serum iron test doesn’t really provide a complete picture of someone’s iron status. It’s important to also check Ferritin, Transferrin, and Total iron-binding capacity (TIBC).

Increasing Vitamin B12

If the symptom patterns, serum B12 level, and additional test data all point to a vitamin B12 deficiency, then the obvious next step is to increase B12 levels. This usually requires a multi-pronged approach that may include the following:

- Eat a B12-rich diet: This means following a well-rounded diet that includes plenty of B12-rich foods like eggs, beef liver, clams and shellfish, dairy products (if you tolerate them), fish (like salmon and trout), poultry, and red meat.

- Take B12 supplements: Sometimes it can be challenging to get adequate B12 through diet alone, so it can be useful to take a high-quality B12 supplement like my Methyl B-12 capsules.

- Prioritize gut health: Gut inflammation and disturbances of the gut microbiome will interfere with B12 absorption. So supporting gut health by minimizing inflammatory foods, and incorporating supplements like probiotics, spore-based probiotics, collagen, and Gut Shield can help to increase absorption.

- Lifestyle modifications: Our bodies are complex, and our organ systems are intricately interconnected, meaning there can be numerous factors that may contribute to an imbalance or a deficiency. Exercise, sleep, stress reduction, and emotional wellbeing all play a role.

While the consequences of an ongoing B12 deficiency can be quite serious, the good news is that this imbalance is often quite straightforward to treat and reverse.

For more about how I approach autoimmune disease, nutritional deficiencies, and chronic conditions, check out my new book: Unexpected: Finding Resilience Through Functional Medicine, Science, and Faith. In it, I share my own story of facing life-altering illness, and the process of healing through functional medicine. The book provides practical advice for treating conditions like mold toxicity, cancer, autoimmune conditions, Lyme disease, and more.

END

Jill C. Carnahan, MD, ABFM, ABIHM, practices functional medicine Flatiron Functional Medicine, in Boulder CO. Dr. Carnahan is board certified in both Family Medicine and Integrative Holistic Medicine. She founded the Methodist Center for Integrative Medicine in 2009 and worked there as Integrative Medical Director until October 2010. She completed her residency at the University of Illinois Program in Family Medicine at Methodist Medical Center and received her medical degree from Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago. Her latest book, Unexpected: Finding Resilience through Functional Medicine, Science, and Faith, is an honest unflinching account of her own health challenges, and the practical application of the principles of functional medicine throughout the healing process.