Twenty years ago, “the microbiome” was an obscure little domain within microbiology, and the term probiotic, to the extent anyone had heard it at all, usually meant eating yogurt and fermented vegetables in the vague hope it would promote longevity.

Today, the microbiome is one of the most widely known and fastest growing healthcare phenomena in history. All over social media, ordinary people banter about concepts like “dysbiosis,” “SIBO,” and the “gut-brain axis.” Microbiome research has exploded, sales of probiotic supplements have soared, and the number of microbiome-related products now available is dizzying.

According to one industry-watching firm, the global probiotics market topped $58.2 billion in sales in 2021, and growth is expected to continue at a compound annual growth rate of 7.5% until 2030. Other analysts expect global sales to hit $133 billion by the end of the decade. The International Probiotics Association estimates the US market alone to be around $7 billion annually.

A Simple Narrative

The spectacular growth of public interest in all things microbiome is based, at least in part, on a compelling, easily-grasped, good vs evil narrative:

Our gut is—or should be—a haven for “good bugs, friendly flora that foster a GI environment conducive to thorough digestion, regular bowel movements, and overall health. But there are also “bad bugs,” pathogenic organisms that disrupt normal gut function and trigger disease.

And then there are probiotics—good bugs in a pill or capsule. Take some of those, tip the scales in favor of the friendlies, and restore your gut health.

Like so many other aspects of life, the relationship between the microbiome and human health turns out to be far more complex than the simple stories we like to tell about it. For medical professionals, this can create big challenges.

This simple story has its roots in the work of Élie Metchnikoff, a visionary Ukrainian zoologist, considered to be one of the forerunners of modern immunology, and the first person to use the term “gerontology.” During a cholera epidemic in the early 1890s, Metchnikoff noticed that only certain people exposed to the disease actually became sick. He had already begun researching acid-producing bacteria in the GI tract and he was convinced that these organisms held a key to resilience against cholera.

Metchnikoff was deeply interested in longevity. He studied Bulgarian peasants who were reputed to be among the longest-living people in Europe, and concluded that their notable longevity was due to their copious consumption of yogurt containing what was then termed “the Bulgarian bacteria,” now known as Lactobacillus delbruekii subsp. bulgaricus.

Metchnikoff personally began to drink fermented milk daily, and advocated for others to do so, under a general concept he called “orthobiosis.” In the simplest terms, the idea was that by supplying the gut with a daily dose of Lactobacilli, one would favor the growth of the “right” organisms which would outcompete potentially pathogenic ones.

A Complex Reality

In his core principles, Metchnikoff was right about a lot of things. Numerous population studies over the last century have borne out the connections between increased consumption of lacto-fermented foods and lower prevalence of digestive, allergic, autoimmune, and metabolic diseases.

Modern microbiome research has shed light on the myriad commensal organisms living within the human gut, and the ways they affect a wide range of human functions: appetite, sleep cycles, glucose metabolism, hormone regulation, mood, and immunity, just to name a few.

But like so many other aspects of life, the relationship between the microbiome and human health turns out to be far more complex than the simple stories we like to tell about it.

For medical professionals, this can create big challenges. Patients come in with simple questions: “Doc, should I take a probiotic?” “Which is the best probiotic for me?” But the sheer volume of probiotics now available, the vast variety of strains, means there are not always simple answers.

Dan Merenstein, MD, Professor of Family Medicine, Georgetown University, and Director of the university’s Research Programs in Family Medicine, has led 10 probiotic studies since 2006. He’s witnessed the mainstreaming of probiotics in medicine, and the ways in which the scientific narrative about the microbiome has become more complicated.

In a webinar on probiotics and immune system resilience, Merenstein pointed out that there’s good evidence that many common disorders including asthma, atopy, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, ulcerative colitis, irritable bowel syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and various liver diseases are associated with changes in the gut microbiome. People with these diseases often show distinct alterations in their gut flora compared to healthy individuals.

What’s less clear is whether these relationships are causal, or whether probiotic treatments can have real therapeutic impact.

“It’s possible that people with ulcerative colitis get the disease and then their microbiome changes, or it’s possible that the microbiome changes and then they get the disease. We haven’t figured that out…yet,” says Merenstein. “But there’s a lot of interest in this because if we can change peoples’ microbiomes, we could potentially treat things like ulcerative colitis, or obesity.”

Change Agents

Probiotics may have a therapeutic role, but it is important to keep in mind that they are not drugs. In fact, one of the interesting things about them is that the same organism can have bivalent or polyvalent effects on humans.

For example, in the context of antibiotic-associated diarrhea—a common condition for which many people take probiotics—the Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 strain can reduce bowel movement frequency, thus alleviating diarrhea. Yet in the context of constipation, this same bug can increase bowel movement frequency.

“Probiotics are not like drugs that push only in one direction. A laxative is always a laxative. It always pushes in the same direction whether necessary or not. But probiotics push toward the middle, toward balance.”

Arthur Ouwehand, PhD, Professor of Microbiology, University of Turku, Finland

From the pharmaceutical perspective, which shapes much of medical thinking, this seems paradoxical. Drugs typically have discrete, one-directional mechanisms of action,

But it makes sense if one keeps in mind that probiotics do not suppress or amplify a particular biological function the way drugs do. Rather, they are change-agents that cause shifts in the microbial ecosystem.

“Probiotics tend to normalize things,” says Arthur Ouwehand, PhD, adjunct professor of microbiology at the University of Turku, Finland, and one of the world’s experts on probiotics and their impact on human health. Dr. Ouwehand is a member of the scientific advisory team for HOWARU® , International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF)’s line of proprietary probiotic strains.

“It’s about balancing back to a normal state. Probiotics are not like drugs that push only in one direction. A laxative is always a laxative. It always pushes in the same direction whether necessary or not. But probiotics push toward the middle, toward balance,” Dr. Ouwehand told Holistic Primary Care.

The honest answer to the question “What probiotic should I take?” is, “It depends on what outcome you’re hoping to reach.” And that means practitioners need to understand the unique biological activities of various species and strains. That’s no easy task, given the ongoing deluge of new research.

The sciences of genomics and metabolomics are evolving at a stunning pace, and they are giving microbiologists powerful new tools to characterize specific probiotic organisms and their bioactive metabolites down to the molecular level. The challenge is in translating these bewildering details into practical, clinical recommendations.

Interconnected Systems

Further complicating the picture is the fact that “the microbiome” is not a single entity. Though much of the public’s attention has been the gut, in truth there are microbial ecosystems all over the body, and they are interconnected. There’s a microbiome on the skin, in the mouth, the lungs, the conjunctiva of the eyes, the biliary tract, the mammary glands, and the genitourinary tract. These invisible worlds interact directly and indirectly with each other, and with all the major human organ systems.

There’s good evidence that many common disorders including asthma, atopy, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, ulcerative colitis, IBS, rheumatoid arthritis, and various liver diseases are associated with changes in the gut microbiome. What’s less clear is whether these relationships are causal, or whether probiotic treatments can have real therapeutic impact.

Take, for example, the relationship between the gut and the vaginal microbiota. These two ecosystems are distinct but interconnected. Both can profoundly impact a woman’s wellbeing. One main difference between them is that in the gut, high microbial diversity is a sign of health, while in the vagina, it means something’s wrong.

Dysbiosis in the gut, the vagina, or both, is associated with a wide range of disorders. Bacterial vaginosis (BV) and vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) are the most obvious ones, but microbiome changes have also been linked to infertility, fallopian tube inflammation, elevated risk of papillomavirus and HIV infection, premature rupture of membranes, failure of in vitro fertilization, cervical dysplasia, depression, anxiety, and gestational diabetes.

A term like “the microbiome” tempts us to think in terms of objects. But microbial communities are not “things,” they are dynamic systems that change over time. As much as commensal microbes influence human physiology, they are also affected by dietary, environmental, hormonal, and lifestyle factors. In and of itself, aging can alter microbial ecosystems.

Changes Over Time

The gut microbiota tends to change as people age, and seldom for the better, according to Drs. Timothy “Ted” Dinan and John F. Cryan of the APC Microbiome Institute, University College Cork, Ireland, one of the world’s leading microbiome research centers. Aging is associated with “a narrowing in microbial diversity,” and especially a decline in friendly flora, which correlates with declining health status bifidobacteria (Dinan TG, Cryan JF. J Physiol. 2016).

Age-associated microbial changes are implicated in declines of innate immunity, muscle mass, and cognitive function (O’Toole PW, Jeffery IB. Science. 2015).

For example, University of Helsinki researchers analyzed the microbiota of 72 elders with Parkinson’s disease (PD), compared with 72 matched controls. They found marked reductions in Prevotellaceae species in the Parkinson’s patients. There was also a correlation between elevated levels of Enterobacteriaceae and severity of postural instability and impaired gait (Scheperjans F, et al. Movement Disord. 2014).

Again, it is not yet clear whether that relationship is causal. But the available data do suggest that, at least for neuropsychiatric disorders, treatments targeting the gut ecosystem (microbiota transplantation, antibiotics, probiotics) could play a therapeutic role (Dinan TG, Cryan JF. J Physiol. 2016).

Strain Specificity is Key

The vision of effectively treating debilitating diseases with probiotic supplements is alluring. But often, when probiotics have been studied in controlled clinical trials the outcomes are far more modest and equivocal than the observational, epidemiologic, and animal studies led us to expect. In day-to-day clinical practice, the impact of probiotics can be highly variable.

“One strain’s evidence is not evidence of another strain’s efficacy.”

Dan Merenstein, MD, Professor of Family Medicine, Georgetown University

There are many reasons for this. A big one is strain specificity. The biological activity of a particular organism is highly strain-specific. For example, the L. reuteri DSM1793 strain of Latobacillus reuteri has been shown to mitigate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation in small intestinal epithelial cells. But other strains of L. reuteri don’t have this effect, says Georgetown’s Dr. Merenstein.

Similarly, the L. rhamnosus GG strain can boost production of anti-inflammatory cytokines while reducing pro-inflammatory signals. But not all L. rhamnosus strains do this. There are numerous other examples like this.

“One strain’s evidence is not evidence of another strain’s efficacy,” Merenstein says.

This means that when choosing probiotics, one must pay close attention to the strains used in the products, to ensure they are backed by solid clinical data.

The problem is, many commercially-available products do not display strain-specific info on their labels. Merenstein and his colleagues studied 93 commercially available off-the-shelf probiotics, and found that 42 (45%) did not provide strain designations on their labels. “It’s impossible to know what’s in the product or what evidence exists for it.”

The Diet-Microbiome Connection

Another complicating factor is the complex relationship between diet and microbiome. According to gastroenterologist Kenneth Brown, MD, someone’s microbiome adapts to what he or she is eating. People who habitually eat a lot of refined carbs, trans fats, sugar, and highly processed foods will have very different microbial profiles than those who eat healthy plant-rich diets. The microbiome adapts to what someone is eating.

A former antibiotic drug researcher, Brown shifted into natural products several years ago with the launch of Atrantil, a combination of three botanicals–Quebracho Colorado, Horse Chestnut, and Peppermint—which mitigates production of methane gas in the small intestine. Recently, Brown partnered with Microbiome Labs on a new formulation that combines that company’s spore-based probiotics with Atrantil.

“You need to change the microbiome and the diet together. It’s not an either-or. You can’t just change one and not the other.”

Kenneth Brown, MD, founder Atrantil

Based on observations of his own patients, Brown says people often fail to get full benefits from probiotics because they don’t make the concurrent dietary changes that create a conducive environment for friendly gut bugs. Most of the friendly flora we wish to cultivate require a lot of fiber, plant polyphenols, and other phytochemicals. You won’t get that from a Pizza Hut diet.

Likewise, people who make radical dietary changes often get frustrated because their digestive systems, conditioned by years of fast food, can’t break down and fully assimilate the healthy fibrous stuff they’re now eating.

“You need to change their microbiome and their diet together. It’s not an either-or. You can’t just change one and not the other,” says Dr. Brown, who practices in Plano, TX.

In other words, a probiotic alone is rarely enough to remedy disorders that are rooted in a lifetime of bad dieting.

Probiotics & Antibiotics

One of the strongest indications for probiotics is for reducing the side effects of antibiotic drugs, especially diarrhea. But this begs important practical questions: If antibiotics cause GI disturbance by killing “friendly” bugs, won’t they also kill off the probiotics? Can probiotics and antibiotics be taken simultaneously, or should they be taken at different times of the day?

Dr. Ouwehand, who has studied this question in depth, says it is a good general rule to allow a few hours’ time between antibiotic and probiotic doses. But several studies show that they can be taken concurrently, with little risk that the drug will obliterate the probiotics. That’s because most antibiotics are highly targeted in the types of microbes they can kill. Even the so-called broad-spectrum ones don’t kill everything.

Plus, antibiotics only kill metabolically active microbes. Most probiotics used in supplements are freeze-dried, so they’re metabolically dormant when ingested, and need time to resuscitate. Therefore, they’re unlikely to be damaged by an antibiotic drug.

Probiotics for Everyone?

Should everyone routinely take probiotics for immune system support?

Dr. Merenstein says there are reasons to believe we should. “They’ve (probiotics) been shown to decrease sick days associated with GI and respiratory (infectious) illnesses.

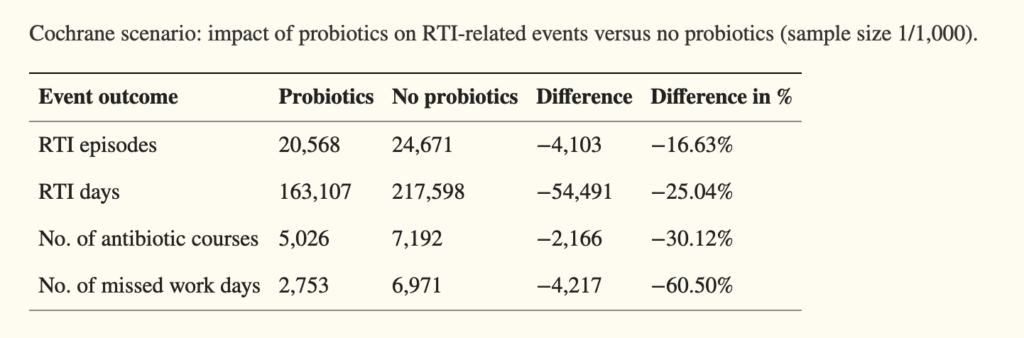

If Americans routinely took probiotics for immune system support, it would result in an estimated cost-savings of $3.73 billion to $4.6 billion in total healthcare spending annually, and avert upward of 19 million sick days just from respiratory infections alone.

He and his colleagues reviewed 17 randomized clinical trials on the role of probiotics in preventing acute respiratory tract infections, acute lower digestive tract infections, or acute otitis media. They found that among infants and children, there was a 29% decrease in the likelihood of needing an antibiotic prescription in the probiotic-treated versus the control groups. When they narrowed their analysis to the five studies with the lowest risk of bias, they found a 54% decrease in antibiotic prescriptions for these three common infections.

The Georgetown group also used data from two well-done metanalyses looking at trends in respiratory infections, and from this, estimated the potential cost-savings if probiotics were used more widely. Their model showed if Americans routinely took probiotics for immune system support, it would result in an estimated cost-savings of $3.73 billion to $4.6 billion in total healthcare spending annually, and avert upward of 19 million sick days just from respiratory infections alone.

“The data are there for probiotics,” Merenstein says. But he stressed that while metanalyses are excellent for detecting general trends, they seldom give the sort of species- or strain-specific information that clinicians really need.

He added that currently there is no RDA for probiotics. Hopefully that will change in the future, as microbiologists continue to elucidate the ways in which commensal microbes can positively affect our physiology, and public health researchers start to catch on.

But it won’t be as simple as the good Doctor Metchnikoff—and those old Dannon yogurt commercials—would have us believe.

It would be nice if we could just solve a problem like antibiotic-associated diarrhea by eating yogurt—something many doctors still recommend. That’s not likely to work, Dr. Merenstein says. First, few of the yogurt brands available in grocery stores contain probiotic strains such as B. lactis Bl-04, B. lactis Bi-07, or L. acidophilus NCFM that are known to help mitigate antibiotic-related diarrhea.

A product calling itself “yogurt” is required by law to contain some live cultures, usually L. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus. But these seldom survive intestinal transit. While they might help to improve lactose digestion in people with lactose intolerance, they’re not likely to have much impact on overall digestive health, says Dr. Merenstein.

Despite its spectacular expansion over the last 20 years, medical understanding of probiotics and the microbiome is still at a relatively early stage. Clinicians working in the field say we’re still far from reaching the full potential benefits that probiotics promise, but things are definitely trending in the right direction.

END