Probiotics could be an important piece of the therapeutic puzzle for people with hepatic cirrhosis and other forms of progressive liver disease.

Research from around the world is shedding light on the so-called “gut-liver axis” and the ways in which the gut microbiome affects liver function, both negatively and positively. This work opens up promising new options for treatment of advanced liver diseases, as well as other metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes.

“We still need more studies, but I am very confident that probiotics can have an important role in preventing the decline of liver function,” says Vanessa Stadlbauer-Köllner, MD, a clinical gastroenterologist in the Department of Gastroenterology & Hepatology at the Medical University of Graz, Austria, and a microbiome researcher at the Center of Biomarker Research (CBmed), also in Graz.

“They will hopefully soon become part of the routine care of patients with liver cirrhosis.”

Dr. Stadlbauer-Köllner, who heads the Medical University’s Liver Transplantation Outpatient Clinic, has been at the forefront of gut-liver axis research for more than a decade. She believes microbiome modulation via oral probiotics has great potential to mitigate the ruthless progression of cirrhosis. It’s a trajectory she’s seen all too often in her patients, and one she hopes her work will help to avert.

“I am very confident that probiotics can have an important role in preventing the decline of liver function. They will hopefully soon become part of the routine care of patients with liver cirrhosis.”

–Vanessa Stadlbauer-Köllner, MD, Directorl Liver Transplantation Outpatient Clinic, Medical University of Graz

Liver cirrhosis is the 11th most common cause of death in the US, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects more than 65 million Americans, with a cost burden of $103 billion annually. There’s a pressing need for better therapeutic options.

Dr. Stadlbauer-Köllner and other gut-liver axis researchers are under no illusion that probiotics are a “cure” for cirrhosis. But there’s growing evidence that they can help.

Toxic Translocations

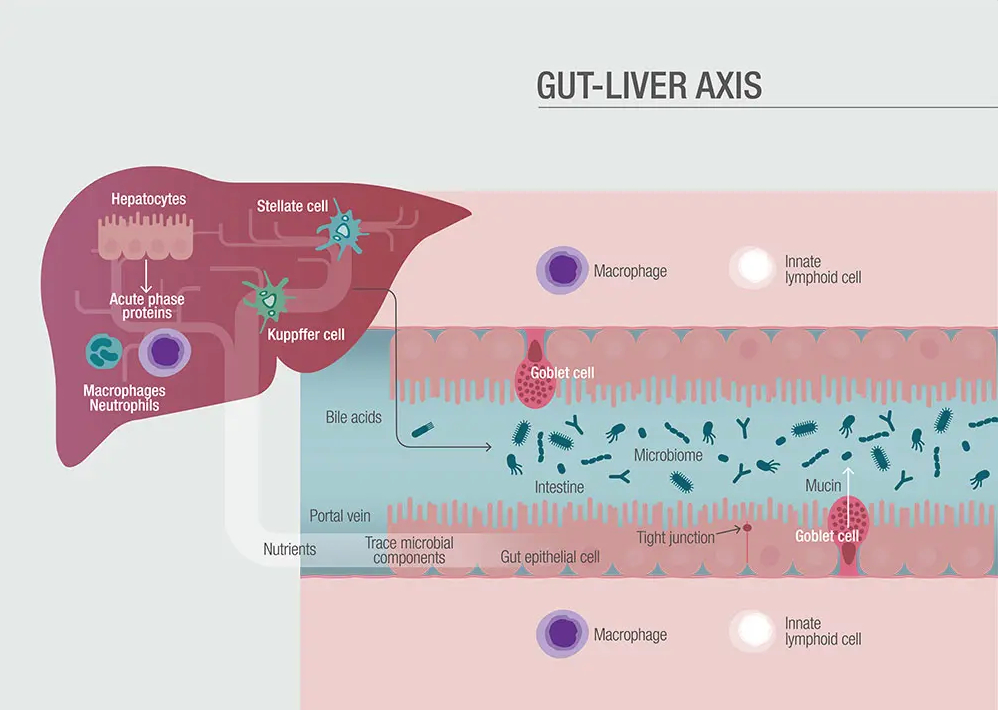

In a normal healthy person, the liver should be more or less sterile; it has no microbiome of its own. But it is greatly affected by what goes on in the gut. In disease conditions, bacteria and bacterial products like endotoxins can translocate from the gut into the liver where they overwhelm the organ’s clearance mechanisms and cause problems.

The gut and liver communicate bidirectionally through the biliary tract, the portal vein and the systemic circulation. Metabolic products of “friendly” intestinal bacteria can positively influence liver function.

But intestinal dysbiosis and increased intestinal permeability leads to translocation of microbes and endotoxins from gram-negative bacteria, or β-glucan from fungi, as well as microbial DNA, all of which can trigger inflammation and impair liver function.

Bacterial infections are common complications of cirrhosis. They arise, in part, because the immune systems of these patients are highly impaired. Oxidative burst, phagocytosis, and neutrophil migration—key first-line defense mechanisms against bacterial pathogens– are usually dysfunctional.

By normalizing the intestinal microbiome, certain probiotics may be able to decrease toxic translocations, and mitigate inflammation, while simultaneously stimulating neutrophil responsiveness.

Immune System Effects

Stadlbauer-Köllner told Holistic Primary Care that her interest in the gut-liver axis arose out of earlier research on immune system abnormalities in cirrhosis patients.

“Initially I was very interested in the question of whether the immune system works well—or not—in patients with liver cirrhosis.”

During a research stay in London between 2006 and 2008, she was studying neutrophil granulocytes. “This is the first barrier of defense to fight pathogens. These neutrophil granulocytes don’t really work well in liver cirrhosis. We did our first study using a single probiotic strain that was given to these patients via a milk drink, and we saw a slight improvement in this neutrophil function. When I came back to Graz, I wanted to replicate this as a placebo-controlled study in a larger number of patients to prove this.”

She worked closely with Institut Allergosan, an Austrian probiotic manufacturer that had developed a multispecies probiotic using strains that, based on cell culture studies, are likely to improve gut barrier integrity and immune function.

This probiotic combination is comprised of the following species and strains: Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Lactobacillus brevis W63, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, Lactococcus lactis W19, and Lactococcus lactis W58. It is marketed in the Netherlands as Ecologic Barrier (Winclove), and as Hetox (Omni-Biotic) in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, and the US.

Stadlbauer-Köllner and colleagues enrolled over 100 patients, aged 18 to 80 years, with histologically and radiologically-confirmed liver cirrhosis. The patients were randomized to 6 months of either the multispecies probiotic, 6 g per day (N=44), or an inert maize starch placebo (N=36). The probiotic powder provided 2.5 x 109 colony-forming units per day. After 6-months of treatment, the investigators followed the subjects for an additional 6 months.

Among the 16 probiotic patients with baseline scores above 7, six (38%) had improvements and seven (44%) remained stable with no decline in liver function following probiotic treatment. No such improvements were seen among the placebo-treated patients.

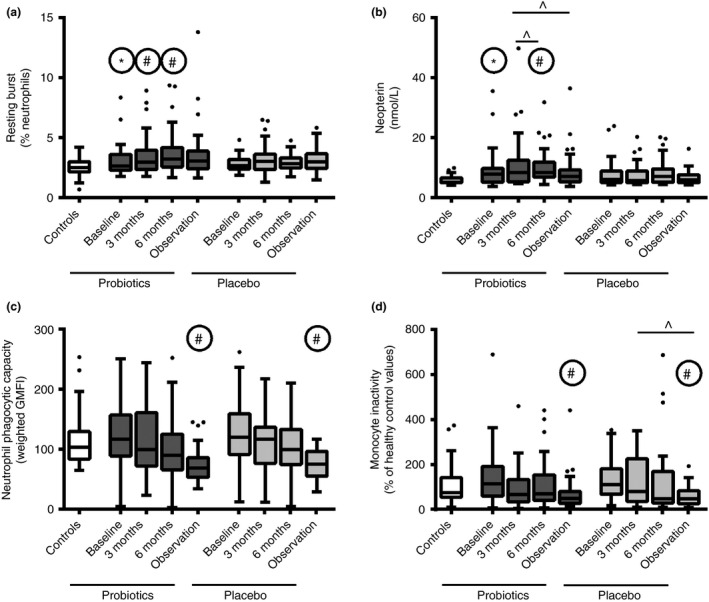

By the close of the treatment period, they saw a significant though subclinical increase in neutrophil resting burst level (2.6–3.2%, P = 0.0134) and neopterin levels (7.7–8.4 nmol/L, P = 0.001) among the probiotic-treated patients, but not in the placebo group. The neopterin surge, along with an increase in neutrophil production of reactive oxygen species, contributed to an overall improvement in antimicrobial activity (Horvath A, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016).

Improved Liver Function

Although there was little difference between the two groups in terms of gut barrier function or bacterial translocation, the probiotic-treated patients showed small but significant improvements in liver function, as indicated by reduced Child-Pugh scores.

The Child-Pugh assessment is a composite of five measures–total bilirubin, serum albumin, prothrombin time, INR, ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy. It is the most widely used standardized assessment of cirrhosis and its prognosis.

Scores in the range of 5-6 points (Class A) correlate with a near 100% one-year survival rate and an 85% two-year survival. Scores of 7-9 (Class B) reduce predicted one-year survival to 80%, and two-year survival to 60%. For patients with scores above 10 (Class C) one-year survival drops to 45%.

The average baseline Child-Pugh scores were 6 for the probiotic group and 5 for the placebo group; in both groups, baseline liver function was still fairly strong.

Among the 16 probiotic patients with baseline scores above 7, six (38%) had improvements and seven (44%) remained stable with no decline in liver function following probiotic treatment. No such improvements were seen among the placebo-treated patients. The probiotic group also showed small but significant improvements in MELD (Model of End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, a composite survival predictor based on serum bilirubin, serum creatinine, and INR prothrombin time.

“This was very striking,” says Dr. Stadlbauer-Köllner. “Because usually you cannot improve liver function in liver cirrhosis with any kind of treatment. Yes, you can improve function when you take away the toxic stimulus that causes liver cirrhosis—like when you treat the hepatitis B or C, or when the patients stop drinking alcohol. But right now there’s no drug or anything that improves Child-Pugh scores. When your patient has cirrhosis, and no chance to treat underlying disease, and no chance to receive a transplant, you just watch your patient deteriorate over time.”

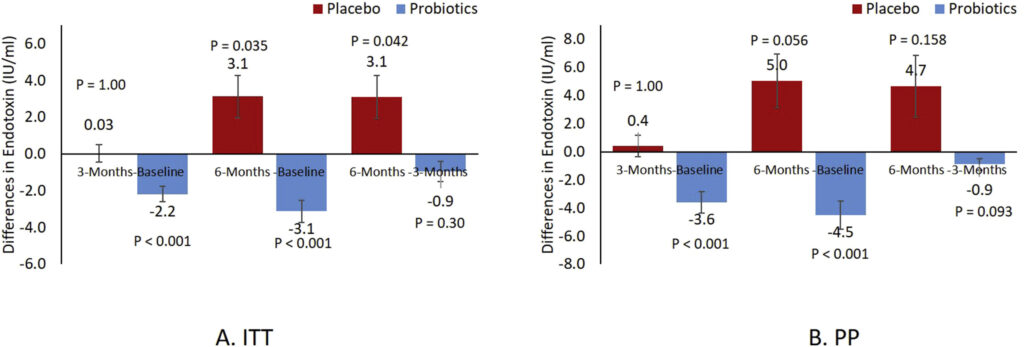

The Graz findings are in accord with a 2004 study from researchers at Capital University of Medical Sciences, Beijing, showing that microbiome modulation using a “synbiotic preparation” of 4 non-urease producing bacteria (Pediacoccus pentoseceus, Leuconostoc mesenteroides, Lactobacillus paracasei, and L. plantarum) could improve liver function and reverse symptoms of minimal hepatic encephalopathy (MHE) in nearly 50% of cases. Those effects were attributed largely to a marked decrease in endotoxemia following probiotic treatment (Liu Q, et al. Hepatology. 2004).

In 2014, a research team at the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigargh, India, showed that compared with placebo, 6 months of daily treatment with a popular multi-strain probiotic called VSL#3 reduced the incidence of breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy by roughly one-third, in a cohort of 130 patients with advanced cirrhosis (Dhiman RK, et al. Gastroenterology, 2014).

The Graz team undertook an in-depth analysis of the microbiome composition in fecal samples they obtained from their cirrhosis patients. In the samples from patients treated with the Omni-Biotic Hetox probiotic, they found an increase in bacteria capable of producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

“It is well known that SCFAs improve the gut barrier. This was the proof for the clinical effect we saw in the first study. This made us very happy because we could see that the liver function improvement was not by chance, but by changes in the gut microbiome,” says Stadlbauer-Köllner.

She added that research on probiotics and liver function is still at a very early stage. Her department is planning a large multicenter trial to look at probiotic treatment with liver function changes as the primary endpoint.

New Options for Type 2 Diabetes

Probiotics also hold promise for patients with T2D, says Dr. Stadlbauer-Köllner.

“In diabetes we see changes in the gut microbiome, in the gut barrier function, and the immune system. There are two placebo-controlled studies—one from Poland, one from Saudi Arabia–using the same Omni-Biotic Hetox product. Compared to placebo, the treated patients showed improvements in glucose metabolism. We also found improvements in lipid metabolism, and in gut barrier function.”

In the Saudi study, which reported data on 30 patients newly diagnosed with T2D, showed a 70% reduction in circulating endotoxin levels among the probiotic-treated patients, compared with the placebo. This correlated with a significant 3.4-point drop in HOMA-IR scores.

“Those who took the probiotic lost 2.5 cm of their hip circumference. They didn’t lose weight but they did lose fat. That’s a very interesting finding,”

–Vanessa Stadlbauer-Köllner, MD

The investigators also observed meaningful decreases in inflammatory signals like TNFα, IL-6, and CRP, and resistin. There were also reductions in total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, as well as an increase in adiponectin, all of which point to a potential cardioprotective effect (Sabico S, et al. Clinical Nutrition. 2019).

An earlier study, involving 78 treatment-naïve Saudi Arabians newly diagnosed with T2D, showed that treatment with this multi-strain probiotic led to a “modest but significant” 1.1% increase in waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) not seen in the placebo group. This improvement in abdominal adiposity occurred without any changes in diet or physical activity level, and correlated with a 64% decrease in HOMA-IR (Sabico S, et al. J Transl Med 2017.)

But surprisingly, there were no changes in weight or BMI. “Those who took the probiotic lost 2.5 cm of their hip circumference. They didn’t lose weight but they did lose fat. That’s a very interesting finding,” says Dr. Stadlbauer-Köllner.

Though these effects were, admittedly “not huge,” she believes they are meaningful given the difficulty of obtaining metabolic changes in patients with T2D.

Again, they should not be construed as a “cure” for diabetes. But “as part of the care bundle, probiotics could be very beneficial.”

Offsetting PPI Problems

Stadlbauer-Köllner also sees a role for probiotics in offsetting the negative impact of proton-pump inhibitors. PPIs are among the most widely prescribed drugs worldwide, and they can be highly detrimental to the gut microbiome. This is especially true in people who already have liver cirrhosis.

“In patients with chronic diseases like cirrhosis, when they have to take a PPI, this causes a certain type of dysbiosis,” she explained. “We find oral bacteria in the stool microbiome that normally don’t belong there. Usually when we swallow, the oral bacteria are killed by gastric acid. When you don’t have a lot of acid because you take a PPI, these organisms can go further down. If you are perfectly healthy, this is not a big deal. But when you have cirrhosis, certain bacteria that cause this so-called “oralization” are associated with a higher risk of complications, and even a higher risk of death.”

Preliminary experiments suggest this may be somewhat reversible with probiotics. Stadlbauer-Köllner’s team is working with Institut Allergosan to identify specific probiotic strains that can counter these “oralization” bacteria, with an eye toward developing and testing a commercially viable product in the future.

Questioning “Colonialism”

The popular notion that probiotics work by colonizing the gut is questionable, according to Dr. Stadlbauer-Kollner—at least for the various strains she has studied.

The improvements in gut barrier integrity and liver function her team have seen in their study of cirrhosis patients are not permanent and persistent. In most cases, it takes weeks to months of probiotic supplementation to obtain the desired metabolic and immunologic benefits, and if patients stop taking the probiotics, the microbiome effects disappear and the cirrhotic process resumes its natural course.

“Probiotics need to be an ongoing, chronic treatment,” she explained.

“So far, I’m not aware of any good data that any of the commercial probiotics are long-lasting colonizers. These bacteria usually belong to the species that naturally occur only in low abundance in the microbiome. So, this approach is not just about introducing and permanently planting these organisms. It is about reversing a dysbiosis. And if you treat underlying health conditions, you restore the ecosystem, but not necessarily by colonizing the microbiome.”

It may, in fact, be a good thing that the organisms do not colonize. Many of the species and strains that people take as probiotic supplements, though “friendly,” are not really endogenous to the human GI tract. Though adverse effects from probiotics are infrequent and generally mild—GI disturbance, flatulence–they can and do occur in some people. In a sense, it is better that these bugs do not permanently set up shop.

“I’m not aware of any good data that any of the commercial probiotics are long-lasting colonizers. These bacteria usually belong to the species that naturally occur only in low abundance in the microbiome. So, this approach is not just about introducing and permanently planting these organisms. It is about reversing a dysbiosis.”

–Vanessa Stadlbauer-Köllner, MD

The situation may change in the near future. Stadlbauer-Kollner says a number of research teams as well as supplement companies are exploring the probiotic potential of various “next generation” probiotics like Faecalibacterium and Akkermansia. The organisms in these genera produce beneficial SCFAs, and according to early animal studies, they are true colonizers.

But they are strict anaerobes, and very difficult to produce in large-scale industrial fermenters, as would be necessary for widespread use as probiotic products. In most countries, they also fall outside the official regulatory definition of “probiotics,” which is restricted to microbes originally associated with fermented dairy or vegetables.

Strain Selection is Key

“Should I take “a” probiotic?” It’s a question you’re probably hearing from more patients these days.

There’s no question that the general public is highly aware of the explosion in microbiome research, and there are plenty of companies marketing the potential benefits of probiotics.

The answer to that question, according to Dr. Stadlbauer-Kollner, depends on a patient’s overall health, the specific conditions with which he or she struggles, and the specific probiotic organisms under consideration. It’s not a simple matter.

“These bacteria have a lot of functions. They have to be considered individually and also in combination with other bacteria. Some probiotic organisms displace other potentially pathogenic bacteria, colonize specific niches in the microbiome, and eat the food of the pathogens so the latter can’t grow. That’s thought to be an important mechanism in preventing C. difficile diarrhea, for example.

“But the probiotics can be metabolically active themselves—they produce SCFAs, and vitamins like vitamin K and vitamin B12. Some can produce antimicrobial peptides. They communicate with the intestinal immune system, and change the expression of cytokines. They also have direct effects on gut barrier by regulating tight junctions.”

She stressed that probiotics can affect human biology at a lot of different “leverage points.” So, the choice of whether or not to supplement—and with what organisms—requires careful assessment of a patient, and equally careful selection of strains and species.

She strongly advised against shotgun supplementation with random strains. “There’s a study showing adolescent obesity got worse after probiotic supplementation, because the organism they used increased energy uptake by the microbiome. So, it had the opposite effect from what was intended. It was making the kids more obese.”

There’s a bright future for probiotics in the context of treating serious gastrointestinal and metabolic diseases. But practitioners and their patients need to proceed carefully.

-END-