“It’s hard to develop new probiotics. It takes a lot of work, and a lot of expertise,” says Wesley Morovic, leader of the Probiotic Genomics team at IFF, an international ingredient company that owns the Howaru brand of probiotics.

From its humble beginnings as an offshoot of dairy production, the probiotics industry has evolved into a sophisticated global enterprise focused on identifying potentially helpful microbes and finding optimal ways to use them.

Where early probiotic development was based largely on observation and educated guesswork, the process today involves precise genomic and metabolomic analysis.

The ‘omics revolution has given microbiologists a more detailed picture of the myriad metabolically active compounds produced by commensal organisms, Morovic explained in a recent interview with Holistic Primary Care.

In light of this knowledge, product developers at companies like IFF’s Howaru, as well as Omni-Biotic, Lallemand, ADM and others, can select and cultivate strains with an eye toward specific clinical benefits.

“In the past the probiotics industry has not been good at determining why the probiotics have the benefits that they do. But with genomics and metabolomics, now we’re able to do that work.” The next generation of probiotics, Morovic predicts, will deliver more predictable, targeted effects.

A Vast World

The gut microbiome is vast. Really vast. Last year, the European Bioinformatics Institute pooled more than 200,000 distinct genomes from human gut microbes with the goal of creating a definitive genetic database. Seventy percent of the organisms they identified were previously unknown, and had never been cultured in a lab.

That’s more than 2,000 newly discovered bugs on top of the thousand or so that we’ve known about for decades.

Faced with this dizzying number of potentially beneficial—or problematic–organisms, how do researchers decide which ones belong on the retail shelves and in the clinics?

Morovic, who leads a team of five charged with translating early stage research into commercially viable products, cited several key considerations:

- Strong evidence of health benefits from ingesting a particular species or strain

- Clear indication that a strain produces one or more bioactive compounds—enzymes, polysaccharides, short-chain fatty acids, proteins, or hormone precursors–likely to confer benefits relevant to specific clinical conditions

- Good safety profile

- Ability to ferment the microbes at industrial scale

- Viability and stability in common usage forms (ie, capsules, liquids, food ingredients), in typical transport and storage conditions.

Bug Discovery

As is the case with many probiotic producers, IFF’s Howaru has its roots in the dairy industry, beginning over 100 years ago as a supplier of enzymes and other ingredients for cheese-making. Many of the company’s core “legacy” strains of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium originally came from dairy food production.

The company has two major R&D and production facilities in the US; one in Madison WI, and the other in Rochester, NY. It also has sister sites in Europe and Asia, where researchers are scanning traditional fermented foods for potentially beneficial microbes. In total, IFF Health employs hundreds of scientists focused on probiotic development and production.

Asian countries, where fermented vegetables have long been dietary staples, tend to be ahead of the curve on probiotic research.

Other leads for potentially beneficial bugs come from university labs. IFF has longstanding partnerships with research centers all over the world, including North Carolina State University, and the University of Helsinki in Finland.

“Within the next five years, we’re going to shift from empirical approaches, basically trial and error, to a true quantification of efficacy in real life conditions. We will be capable of looking at a specific patient or sub-population of patients with particular conditions, and predict which microbes will be best, and which individuals will most likely respond. We’re not there yet but we’ll be there soon.”

–Sebastien Guery, VP of Global R&D, IFF/Howaru

“Industry scientists are often limited in ways that university researchers are not,” says Morovic. “So, a lot of the stronger claims about newly characterized microbes come from the universities. Sometimes they find rare and interesting organisms. Then the question becomes, how do you make it on an industrial scale? Universities can’t generally do that kind of research, but we can.”

When it comes to translating basic research into commercial probiotics, the question of scale-up is a big one.

Scaling Up

IFF’s largest fermentation tanks hold 150,000 liters of aqueous growth medium. These are used to produce the most in-demand strains. Less popular specialty strains are grown in smaller fermenters with volumes of 30,000 to 40,000 liters.

The process begins with a small 1mL vial of the desired microorganism. This goes through a series of multiplications, in tightly controlled conditions, from a few milliliters all the way up to the large steel containers holding thousands of liters. At each step, technicians check for viability of the desired strain, and for absence of contaminants.

For most organisms, the time interval from seed sample to large tank is roughly two days, though some scale much faster. Growth rates are highly species-specific.

Typically, the scale-up occurs over a small number of microbial generations, a variable to which IFF’s Howaru teams pay very close attention.

“We need to know how many generations are happening through the scale-up, because we need to control for genetic drift. We want to avoid random mutations that can happen in the fermenters,” said Morovic. “Mutation is part of biology, but we want to minimize it, so the phenotype in the end product matches the original phenotype in the vial.”

Once microbial growth hits its maximum, the next step is to separate the live bacteria from the spent growth medium. The dense bacterial concentrate—which Morovic says has the consistency of a milkshake—is then frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried to remove moisture. This renders the bacteria quiescent; they’re still alive but no longer metabolically active.

For a particular bug to be a good probiotic candidate, it must be able to withstand this stressful concentration and freeze-drying process. Howaru researchers have found adjuvants that can be added to growth media to stabilize cell membranes, prevent lysis, and help organisms survive the production process.

As probiotic development becomes more precise, strain designations will become even more important. “Benefits are often strain-specific. It is something to pay attention to.”

–Wesley Morovic, Head of Probiotic Genomics, Howaru

The company has a specialized team to assess strain viability across dosing forms, temperature conditions, and storage containers. All of this factors in to the viability of the finished products. Morovic points out that some companies label their products with claims about “total cell count at time of manufacture.” This can be misleading because it does not guarantee viability through the product’s expiration date.

“Stability means survivability over time. Our R&D and QC teams test very carefully, looking for long term stability over 2-3 years. You want the label to say the CFUs (colony-forming units) are guaranteed through date of expiration.”

Species vs Strain

Good probiotic studies, and the products developed from them, should include clear information about the species and strain(s) being used. It is an important detail because it ties back to genotype, which will determine physiological effects.

Many people are confused about the distinction between “species” and “strain.” Morovic suggests thinking of it in canine terms. All dogs belong to the species, Canis familiaris. Within that species there’s a wide variety of sizes, shapes, colors, and temperaments which we call “breeds.” In the microbial world, there can be a similar spectrum of variance within a given species. These are called strains.

A strain is distinguished as such because it has genetic and phenotypic features that differ from others within the same species. Think of two beagles, one with a bi-color tan and white coat, the other with a tri-color tan, white, and black coat.

Two strains of L. acidophilus may diverge genetically by as much as 5%. But the difference could be just one or two base pairs. The point is, these genetic differences translate into biochemical and metabolic traits that affect how the organisms interact with our human physiology. For example, one strain may have genes enabling it to produce butyrate or other key short-chain fatty acids, while another does not.

Within a bacterial species there can be great diversity. Consider B. longum: some strains, especially in B. longum subsp. infantis, can break down oligosaccharides in human breast milk rendering them more readily assimilated—a major plus for human infants. Other strains of B. longum do not. Some can convert a wide range of milk sugars, others have a more limited repertoire.

Two strains of L. acidophilus may diverge genetically by as much as 5%. But the difference could be just one or two base pairs. These genetic differences translate into biochemical and metabolic traits that affect how the organisms interact with our human physiology.

As probiotic development becomes more precise, strain designations will become even more important. “Benefits are often strain-specific. It is something to pay attention to,” says Morovic. All of IFF’s trademarked Howaru strains are supported by dozens of preclinical as well as human clinical trials.

Condition-Specific Probiotics

“We are capable now of sequencing microbial genomes as well as performing metabolomic analyses at much more reasonable costs compared to a decade ago. As a result, we can get insights from huge masses of data via AI systems, and identify non-obvious correlations between the microbiome composition, the microbiome function, and the health of its host,” says Sebastien Guery, IFF’s Vice-President of Global R&D Venturing.

A pharmacist by training, Guery has decades of experience at major pharmaceutical companies including Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sandoz. He believes we are on the verge of a revolution in human health.

“Within the next five years, we’re going to shift from empirical approaches, basically trial and error, to a true quantification of efficacy in real life conditions. We’ll have bigger populations of subjects, better measures of the efficacy for use of probiotics,” he told Holistic Primary Care.

“We will be capable of looking at a specific patient or sub-population of patients with a particular condition, and recommend which microbes will be best, and which individuals will most likely respond based on specific biomarkers. We’re not there yet but we’ll be there in the near future.”

The current explosion of microbiome research and the emergence of sophisticated condition-specific probiotics has revealed one of conventional medicine’s biggest blind-spots.

Guery identified several clinical fields ripe for microbiome innovation:

Digestive Disorders: Most gut-related disorders—but especially irritable bowel and ulcerative colitis—are linked to the state and quality of the microbiota, and are potentially remediable with probiotic interventions. Guery said IFF is highly focused on gut inflammation, as are many other probiotic developers.

Immune Related Illnesses: A host of recent research indicates that the microbiome interacts closely with the immune system. It can help to prevent and/or thwart infectious illnesses such as the common cold. There’s also evidence that microbiome factors can desensitize allergies, potentially decrease the severity of asthma episodes, improve the efficacy of certian cancer therapies, and potentially slow the progression of autoimmune diseases.

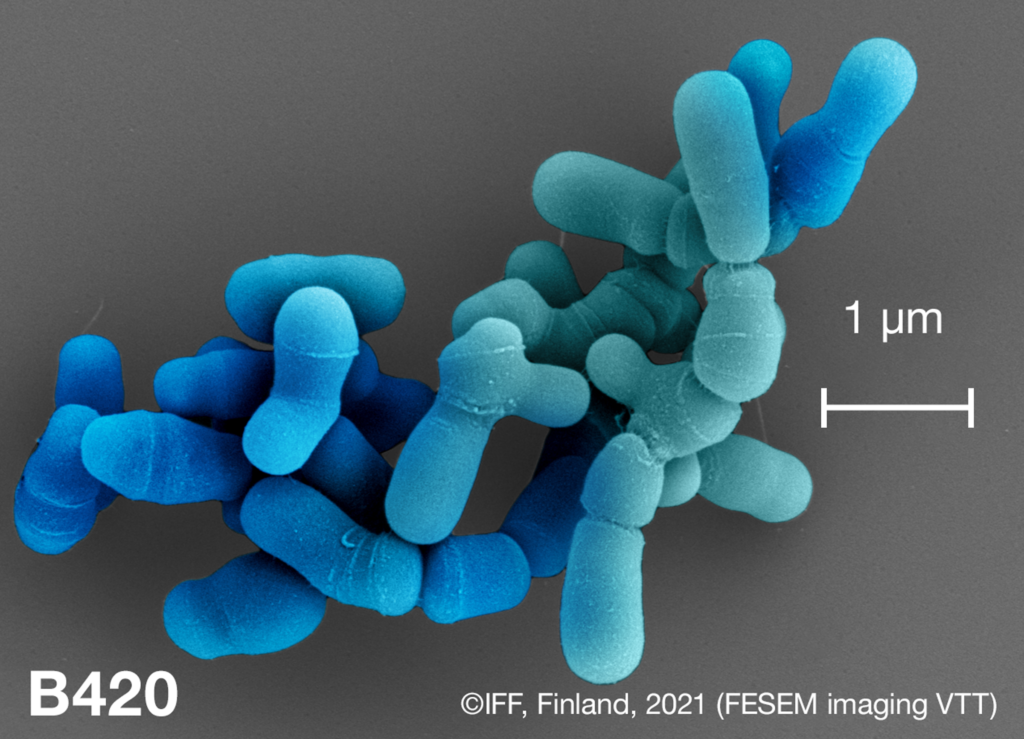

Metabolic Dysregulation: The microbiome play a role in metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and obesity. These can be addressed not only via diet but also via administration of live microbes. There’s already evidence that the microbiome can influence insulin sensitivity. Additionally, one of IFF Health’s Howaru strains– B. lactis B420–has been linked to better weight management in obese adults.

Rationally-Designed Consortia

On the horizon is the possibility of creating what Guery terms “rationally designed microbial consortia.” These are carefully tailored combinations of well-characterized microbes that grow together to create small synergistic ecosystems.

“Based on known properties of the microbes we can assemble combinations to maximize efficacy. You select microbes with the best properties, but also best team players that are able to synergize together. Guery says IFF is in active collaboration with a Belgian company called MRM Health working in this direction.

“We know they (probiotics) have benefits. We know they produce various metabolites. But the next big part of the story is about how they affect our genes. We can now measure host genetic responses to probiotics.”

–Sebastien Guery

“There’s a whole new field emerging around this inter-kingdom communication, the crosstalk between the microbes and our organs. Some molecules we thought were “human only” are actually produced by our gut microbes. This is the result of co-evolution between humans and microbes. In other words, we learned to speak the same language so we can help each other survive,” Guery reflected.

The current explosion of microbiome research and the emergence of sophisticated condition-specific probiotics has revealed one of conventional medicine’s biggest blind-spots. “We’re starting to understand how complex is human physiology, and that we can’t just look at the ‘human’ part,” says Guery.

“Knowing what I know now, I would have done drug development very differently. When I started my career, we looked at the intricacy between small molecules and human physiology with the goal of treating central nervous system illnesses. But we were completely omitting one major part: the gut microbiome, which plays a role way beyond the gut”

Along with IFF Health, several other companies are also bringing forward new condition-specific probiotics, and they’re gaining considerable market traction.

Recently, the i-Health division of DSM—one of the world’s major supplement ingredients manufacturers—announced a partnership with ADM on the development of a probiotic specific for weight management. This new version of the popular Culturelle brand, will include ADM’s BPL1 strain of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. Lactis, which was shown to reduce visceral fat and body mass index in human subjects.

The new product joins a line of other Culturelle formulations for immune support, management of IBS, and other conditions.

Omni-Biotic, the consumer-facing division of AllergoSan—an Austrian probiotic company—was recently honored with Nutra Ingredients’ 2021 Probiotic of the Year award for its 9-strain Stress Release formula, targeting the gut-brain axis.

The effect of gut microbes on the brain and central nervous system–a field often referred to as “psychobiotics”— is one of the hottest domains of microbiome research these days.

Another recent trend is the development of probiotics not from fermented dairy or vegetable products as was the case for many years, but directly from human gut commensals.

Next Generation Probiotics

Guery says he is particularly excited about emerging research on inter-kingdom communication, the close interactions between microbes and the immune system, and the ways in which probiotic organisms can influence even drive human gene expression. “We know they (probiotics) have benefits. We know they produce various metabolites. But the next big part of the story is about how they affect human gene expression.”

Microbes may be influencing our genes, and there’s no question we are modulating theirs’. None of Howaru’s commercial strains are genetically modified organisms (GMOs), but there are companies marketing gene-edited probiotic organisms though that fact may not be readily disclosed.

“We’ve tried historically to stay close to naturally occurring microbes. These are microbes that we know, that come from humans or have been consumed by humans. The safety profiles are good, the efficacy profiles are good,” states Guery. “That being said, there is definitely a next wave of therapeutic products that will come to market in the next decade using GMOs engineered to express specific therapeutic proteins or metabolites.”

He added that genetic modification of microbes to produce drug-like therapeutic molecules is definitely a trend in the pharmaceutical industry.

A more mundane concern is the way in which public enthusiasm about probiotics is fostering a Gold Rush mentality among consumer products companies.

“Right now, the microbiome is extremely fashionable and appealing to various players, some more serious than others. A few bad players can really damage the credibility of this field. It took us a very long time to get to the level of understanding we now have. If we have bad players, it could be major setback in terms of bringing safe and effective products to market.”

As more medical professionals become educated about the new science of probiotics, they will be better able to guide patients toward products based on solid evidence, formulated according to clear and rational principles, and manufactured to exacting quality standards.

END