Doctor suicide is a painful reality that hospitals, clinic networks, and medical schools go out of their way to deny.

But with the emergence of a documentary called Do No Harm, and a surge of media attention following the suicide of Dr. Lorna Breen during New York City’s first COVID peak, healthcare leaders are finally being forced to reckon with the ugly truth that in many institutions, medicine has become a culture of abuse.

American physicians kill themselves at an alarmingly high rate. A least one doctor commits suicide every day in the US, according to research presented two years ago at the American Psychiatric Association’s annual meeting. Investigators at the Harlem Hospital Center in New York conducted a systematic literature review of physician suicides and identified a staggering rate of 28 to 40 per 100,000––more than twice the general population’s suicide rate of 12.3 per 100,000.

The review also showed that doctors have the highest suicide rate among all professions, including jobs in other high-stress fields like the military or law enforcement.

Those statistics were identified before COVID-19. In 2020, the pandemic is only accelerating existing trends. Stories of medical professionals lost to suicide in the last 5 months are shining new light on long-standing and dangerous shortcomings in our systems of medical education and practice.

A Doctor a Day

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) estimates that 300 American doctors die by suicide each year. These deaths rarely make the news, are seldom fully investigated, and often go unacknowledged for what they truly are.

Hazards of duty? Part of the deal? Comes with the territory?

Only if that “territory” is the United States.

Medicine is a high-pressure job anywhere. But doctors in other countries are not killing themselves at nearly the rates of their American counterparts. According to a 2019 systematic review by Dutheil and colleagues, US physicians are far more likely to commit suicide than their peers worldwide. Medical suicide rates have been rising in this country over the last decade; in Europe, they’ve actually been decreasing.

Why do so many American doctors and medical students take their own lives? And why aren’t their deaths more widely publicized?

Pamela Wible, MD, a family physician by training, has spent most of the last decade documenting and studying physician suicides. As a part of that work, she runs a suicide helpline for medical professionals and students. She’s personally documented nearly 1,500 cases since 2012.

Wible believes guilt, bullying, and exhaustion are three leading causes of suicide in medicine. Physicians, med students, and other healthcare personnel are often subjected to abusive, even dangerous, working conditions. Overwork is common; self-care is penalized.

In many hospitals and clinics, the inevitable pressures of medical practice are compounded by conflicting administrative demands, hostile work environments, retaliatory office politics, racial discrimination, and sexual harassment. It all adds up.

“‘Burnout’ is victim-blaming, and deflects attention from the hazardous working conditions that are illegal in any other industry that values safety, and the human rights violations that are rampant in medical education and beyond.”

—Pamela Wible, MD

Hazing & “Pimping”

It begins with the rigors of medical education, and extends through insurance-based medicine’s emphasis on volume over quality. Young physicians in training are frequently subjected to sanctioned abuse and public humiliation in lecture halls and hospital wards. They’re also severely sleep-deprived—itself a form of torture.

For some suicidal doctors, the problems began when they entered medical school. Med students are typically high-achievers accustomed to ranking at the top of their classes. Once in med school though, some feel for the first time in their lives that they might not really be smart enough, tough enough, or brave enough to become “good” doctors.

Within medical culture, there’s a pervasive fear of being weak, unintelligent, or incapable. That fear drives people to hide their mistakes and imperfections and shy away from seeking help, even when it’s desperately needed.

Some level of pressure and anxiety is to be expected in a career as demanding as medicine. But Dr. Wible sees shockingly toxic elements in US medical culture.

Bullying, humiliation, and hazing are tolerated, sometimes even encouraged as acceptable training strategies. Many doctors can tell stories of getting “pimped,”––an aggressive, rapid-fire style of testing students’ clinical knowledge by asking difficult or intentionally unanswerable questions in class, in the clinic, and even in front of patients.

All that takes its toll.

A 2016 study of med students by the National Institutes of Health and the US Department of State found that, “overall prevalence of depression or depressive symptoms among medical students was 27.2%, and the overall prevalence of suicidal ideation was 11.1%.” Among those who screened positive for depression, only 16% sought treatment (Rotenstein, L et al. JAMA. 2016; 316(21): 2214‐2236).

“There seems to be more mental health distress among first and third-year med students, and definitely for unmatched graduates. In some residency programs, 75% of residents meet criteria for major depression,” Wible says.

Med students experiencing depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts avoid seeking care because they worry they’ll be “outed,” stigmatized, and punished if they do.

The stress and pressure––and subsequent mental health risks––only increase once they transition into actual clinical practice.

They enter an extremely hierarchical system in which they’re often forced to “earn their keep” by filling the most undesirable shifts. Long hours without breaks; weekend and holiday shifts with little time off; isolation from friends, family, and crucial social support—these are not exceptions, but rather the rule for many young doctors.

Sleep Starvation

Sleep deprivation is also a big factor, says Wible.

Going without sleep for extended periods is comparable to alcohol intoxication. Exhaustion erodes cognitive and motor skills, slows reaction times, and compromises task performance. Doctors who are sleep-deprived are also at heightened risk for motor vehicle collisions and hospital-related injuries.

It is not hard to find a physician who can tell tales of falling asleep, or witnessing colleagues drop unconscious to the hospital floor, while making rounds, treating patients, or conducting surgeries. Perhaps you’ve been one of them.

In other high-stress professions–pilots, air traffic controllers, even truck drivers, for example–there are regulations and work-hour restrictions that limit shift lengths, because everyone recognizes that sleep deprivation and overwork impair performance.

Yet our medical system drives doctors—who routinely deal with matters of life and death that hinge on clear, quick judgment—to the point of exhaustion.

Current ACGME requirements permit interns’ duty shifts to run for 24 consecutive hours––up from a previous cap of 16 hours––and 80 total hours per week.

Not only do we permit sleep-starved doctors to administer potentially dangerous drugs, monitor patients on a complex array of equipment, and perform surgeries that require great skill––we expect them to do it all flawlessly––and to be nice about it.

In other high-stress professions…there are regulations and work-hour restrictions, because everyone recognizes that sleep deprivation and overwork impair performance. Yet our medical system drives doctors—who routinely deal with matters of life and death that hinge on clear, quick judgment—to the point of exhaustion.

Exhausted doctors are more likely than well-rested ones to make medical errors, which sometimes kill patients. A 2018 Mayo Clinic study found that physicians who made errors were more likely to exhibit symptoms of fatigue, burnout, and recent suicidal ideation (Tawfik, D et al. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018; 93(11): 1571-1580).

When Epidemics Collide

COVID-19 presented new and unusual stressors for clinicians in viral epicenters like New York City, Washington, DC, and Chicago, where prevalence was highest during the early months of the pandemic.

Emergency medicine physicians and nurses are particularly vulnerable. In centers with very high caseloads they’re working under constant duress, sometimes without adequate protective equipment, in hospitals that were understaffed even before the pandemic. As they treat their patients, they worry about their own risk, and the potential for carrying the virus home to their families.

Dr. Wible, who has provided counselling for suicidal clinicians for nearly a decade, says that since the coronavirus, she’s seen a dramatic increase in the number of calls.

“Volume doubled, and I led group support calls on Zoom to handle the uptick in requests for support,” she reported.

On April 26, Dr. Lorna Breen, a well-respected ER doctor at New York Presbyterian’s Allen Hospital in New York City died of “self-inflicted injuries” at age 49. Her story got the media’s attention, as it represented the convergence of two epidemics: COVID and doctor suicide.

Prior to her death, Dr. Breen had treated many coronavirus patients, and she herself had recently recovered from the virus.

“Make sure she’s praised as a hero, because she was,” Breen’s father, also a doctor, told the New York Times. “She’s a casualty just as much as anyone else who has died.” The elder Dr. Breen also stressed that his daughter, “did not have a history of mental illness.”

In its official public statement, New York Presbyterian used similarly valiant language. “Dr. Breen is a hero who brought the highest ideals of medicine to the challenging front lines of the emergency department.”

But an email to hospital staffers did not immediately identify the cause of Breen’s death, reflecting an attitude of denial and obfuscation that Wible says is the rule, not the exception, among hospital administrators.

Breen’s family and hospital “had to use ‘healthcare hero’ propaganda on her immediately, so that she wasn’t forgotten or thrown to the wind as weak,” Wible told Holistic Primary Care.

“They gave her the hero spin because she was in New York City and had a high position in her hospital. Her family made it clear that she never had any preexisting medical conditions and instead suggested her death was due to the coronavirus, to distance her and the family from the topic of mental health issues.”

This denial contradicts evidence Wible has gathered from the nearly 1,500 cases she has recorded. She finds that ER doctors rank among the top three medical specialists most likely to die by suicide. Psychiatrists, surgeons, and anesthesiologists also have a higher risk than others.

Secondary Trauma

Wible believes secondary trauma plays a big role, at least for the latter two specialties.

Breen’s family insists that she never suffered from prior mental health challenges, but Wible says it’s hard to imagine that a doctor who spent her entire career in the ER never suffered a single blow to her emotional or cognitive wellbeing.

“I believe all emergency medicine doctors have mental health wounds,” Wible said.

It is common to hear clinicians say that experiencing or witnessing a catastrophic injury or illness early in life is what inspired them to pursue medical careers. Wible finds that “many EM doctors have experienced significant trauma in their childhoods––then they go into emergency medicine and are re-traumatized every day.”

Even those who did not experience childhood trauma will invariably incur “occupationally-induced mental health wounds” while working in the emergency department. “If they have not sought appropriate care, then they are still wandering around with those wounds every day,” she said.

It’s Not “Burnout,” It’s Abuse

“This is tough work, even on the best day,” Wible says of the medical life. “Even in the parts of medicine that seem like they could be happy, there is unforeseen, extreme tragedy.”

In our current systems, the inevitable stresses and pressures of caring for sick, injured, and sometimes dying people, are amplified by factors unrelated to patient care.

Micromanagement by senior doctors or hospital administrators; incessant demands for documentation; veiled threat of punishment or legal consequences for errors; poorly managed and understaffed clinics; incessant time pressures. All these factors leave many physicians feeling not only emotionally exhausted, but cynical towards the profession they once loved.

We call it “burnout.” But Dr. Wible warns that this term obscures the abusive nature of our medical system itself.

“‘Burnout’ is victim-blaming, and deflects attention from the hazardous working conditions that are illegal in any other industry that values safety, and the human rights violations that are rampant in medical education and beyond.”

Hospitals treat physicians in ways that “break the UN Declaration of Human Rights,” she suggested. Other medical professionals also experience extreme pressure, overwork, and abuse. But statistically, the suicide risk is much higher for physicians.

Hidden in Plain Sight

Part of the problem is physicians’ uncanny ability to hide their suffering not only from colleagues and supervisors, but from family members and friends. Doctors who experience depression, anxiety, or suicidal ideations often view those symptoms as flaws that must never be exposed. Some worry that admitting psychological or emotional distress will call into question their fitness to practice or, worse, might lead to dismissal.

There may also be expectations from family and friends that someone who has “made it” in such a high-status profession must surely be reaping rewards. Some doctors feel a sense of duty not to disappoint parents, spouses, or other loved ones who’ve also invested and sacrificed to make their medical careers possible.

As a result, few people know when a doctor friend or family-member is contemplating suicide.

Dr. Wible—who had her own struggles with anxiety and suicidality earlier in her career—says there are a few red flags: “Excessively happy doctors are often hiding their emotions and pain.” Additional warning signs may include a recent medical liability case, medical board complaints or investigations, and major life events like divorce.

Denial: A Double Assault

Denial by hospital administrators, family members, and colleagues has only compounded the problem of doctor suicide.

“We create the scenario that takes these wonderful young people and puts them in a situation where they can see the only way out is death––and then we bury their suicides,” Wible said. “It’s like a double assault.”

She pointed out that a number of doctor suicides involving ingestion of prescription drugs were misleadingly reported as “accidental” overdoses. It is certainly possible for physicians to unintentionally take too much medication, but this explanation stretches credibility. MDs get extensive training in pharmaceutical use; that makes them some of the least likely people on the planet to unknowingly over-consume a drug.

Doctors do, however, have ready access to controlled substances, which heightens risk of abuse. According to a 2013 study published in the Journal of Addiction Medicine, 69% of doctors reported that they abused prescription drugs “to relieve stress and physical or emotional pain” (Merlo, L et a. J Addict Med. 2013; 7(5): 349-53).

Physicians also possess an intimate and detailed knowledge of human anatomy, increasing the chances that they will complete a suicide if attempted.

Concealing doctor suicides protects medical schools and hospitals from having to address systemic problems. But sweeping the dirty secrets under the rug only puts other health professionals––and their patients––at tremendous risk.

“Suicide is not the problem; censorship is,” Wible argued. “If we would just speak openly about this crisis, it could be easily solved.”

Effective, evidence-based suicide prevention tools exist––and they can help avert the needless loss of doctors’ lives. “We have the resources to solve this problem. But if we censor it, we can’t make it better. We can’t solve a problem that nobody is acknowledging.”

Get Up, Stand Up

Wible says that to truly shift medical culture in a healthier direction, “we need to normalize the conversation about suicide risk, just like we’ve normalized conversations about blood pressure.”

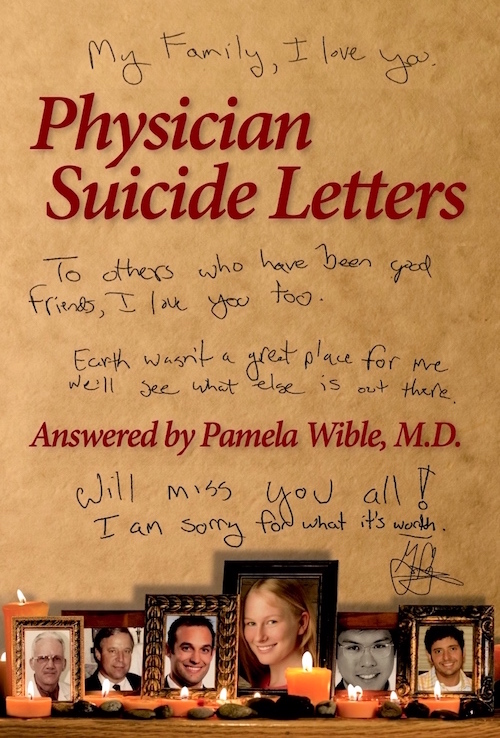

Education is also vital. Two resources she recommends are the documentary “Do No Harm” by filmmaker, Robyn Symon, and her free audiobook of doctor suicide notes, Physician Suicide Letters—Answered, in which she shares her correspondence with numerous clinicians whom she’s helped to avoid suicide.

The key, she says, is providing a forum for self-expression without fear of rebuke or humiliation. “The system of medical education and practice should be set up in a way where people are able to connect with each other honestly, emotionally and spiritually, without punishment,” Wible said.

Fixing the situation will also require system-wide reforms to create more humane working conditions within medical institutions. Wible believes doctors, nurses, med students, and other health professionals need to stand up and fight for those reforms.

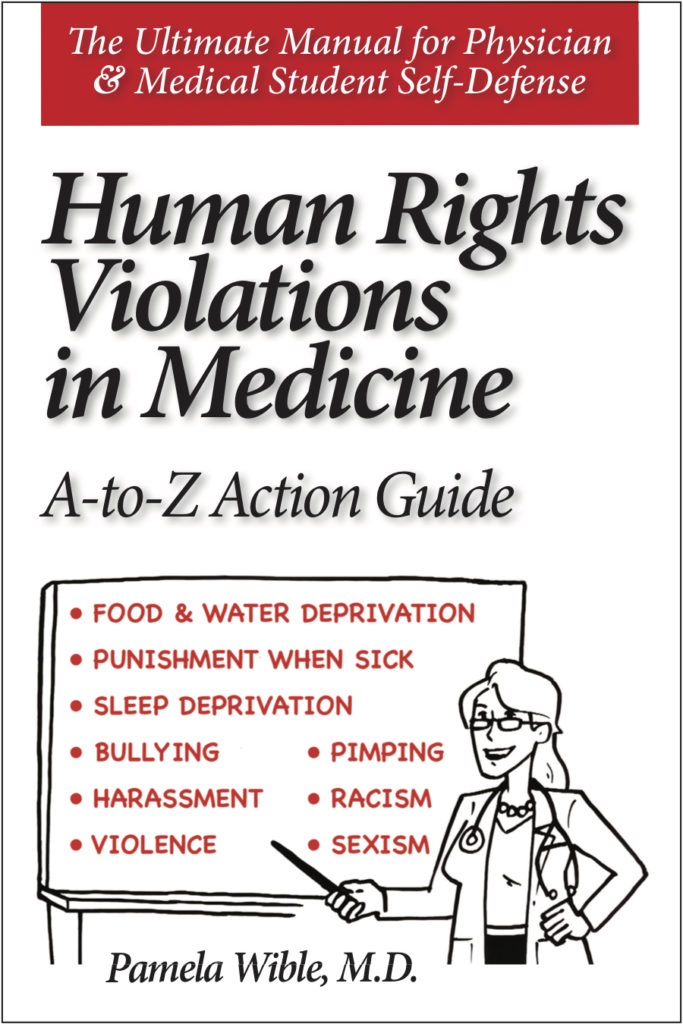

To that end, she recently published Human Rights Violations in Medicine: An A-to-Z Action Guide.

The book documents a spectrum of abusive situations–from food and sleep deprivation to threatening foreign-born doctors and trainees with deportation–that routinely occur in American clinics. It also gives guidelines to help doctors chronicle their own experiences of abuse, and practical action steps for confronting and resolving these situations.

Dr. Wible is certainly not the only physician concerned with doctor suicide, and pushing for change.

Keith Frederick, an osteopath who also served for eight years in Missouri’s House of Representatives, introduced a bill to address mental health in Missouri medical schools after learning that a fourth-year osteopathic student in his community died by suicide just days before graduation.

In the film Do No Harm, Dr. Frederick described suicide as an unacknowledged “occupational hazard” in medical settings. During his years as a legislator (2011-2019), he also sponsored a bill requiring hospitals to examine mental illness and burnout among staff.

Not surprisingly, Frederick’s proposal met initial resistance from Missouri medical institutions. The deans of all six of the state’s med schools co-authored a letter urging legislators not to pass the bill.

Ultimately, though, Frederick and his supporters won-out. The “Show-Me Compassionate Medical Education Act” (MO Senate Bill 52) was signed into law in July 2017. It requires medical schools to provide incoming students with information about available depression and suicide prevention resources. It also granted medical institutions the authority to conduct internal research, without penalty, on rates of depression, suicide, and other mental health issues among medical students.

Thank a Doctor, Save a Life

In addition to raising awareness around suicide risk and prevention, expressions of gratitude can literally help keep doctors alive.

Wible encourages people to “please show appreciation and give thank you cards to your doctors, and ask them how they are doing.”

It might seem simplistic or even silly, but she believes it can be life-saving.

“It can be very hard to reach doctors––they’re often so closed off emotionally. It’s important that they feel validated, normal, and appreciated.” A thank you letter may give a doctor a much-needed dose of positive reinforcement that he or she may not otherwise receive.

Verbal thanks are nice too, but Wible says that penned messages carry an even greater and longer-lasting power. “Thank you notes are huge––especially if they are written. They have a lifespan that goes on for decades––doctors will read and reread them, sit and stare and really soak in the words.”

Clinics and hospitals might also consider setting up anonymous compliment boxes where staff and patients alike can submit thank you notes to their doctors or colleagues.

She also urges medical practitioners to prioritize their own health and self-care. She herself does this by “spend[ing] a lot of time in nature, hiking, gardening, and with my animals.” She also stressed the importance of strong social connections, like the one she shares with her loving partner.

“And most important,” she added, “I get therapy WEEKLY.”

She holds that all med students and doctors should receive “non-punitive, 100% confidential therapy” every week. Whether it’s for preventive or active treatment, breaking down the barriers around mental health support could help avert the tragic doctor suicides on which our current systems prefer to turn a blind eye.

END