What do the stock market and the immune system have in common? More than you might think.

Researchers tracked a small group of finance professionals during a highly stressful period of extreme market volatility. They showed that the heightened stress led to marked shifts in important immune system biomarkers. Participants’ physiological reactions to market-related stress resembled the immune defenses typically triggered by physical health threats like infections.

If the body’s infection defense system responds to financial crisis as if it’s a disease, the implications for personal health are vast.

More broadly, the authors argue, major market events including crashes and share price fluctuations may even have roots in the financial community’s collective physiological response to stress.

“ Physiological changes occurring in the financial community shift risk preferences pro-cyclically. This phenomenon caus[es] investors to take too much risk on the upside, pushing a bull market into a bubble, and too little on the downside, driving a bear market into a crash.”

This analysis, published two years before the COVID pandemic wrought global economic chaos, offers a unique perspective for our current times, when millions are facing the dual challenge of economic hardship and immune health concerns.

The Biology of Risk-Taking

In a 2018 paper posted on Biorxiv, (pronounced “Bio Archive”) a pre-print service run by the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, a team of British investigators described the physiology of 15 male traders at a mid-sized hedge fund in the City of London. The study took place near the end of the European Sovereign Debt Crisis, at a time of declining but still elevated market volatility.

For two weeks, researchers measured participants’ stress and immune responses under real working conditions. They tested for salivary cortisol and four immune system signaling proteins, IL-1𝛽, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-𝛼, three times daily. Sampling occurred at 9am, 12pm, and 4pm on business days.

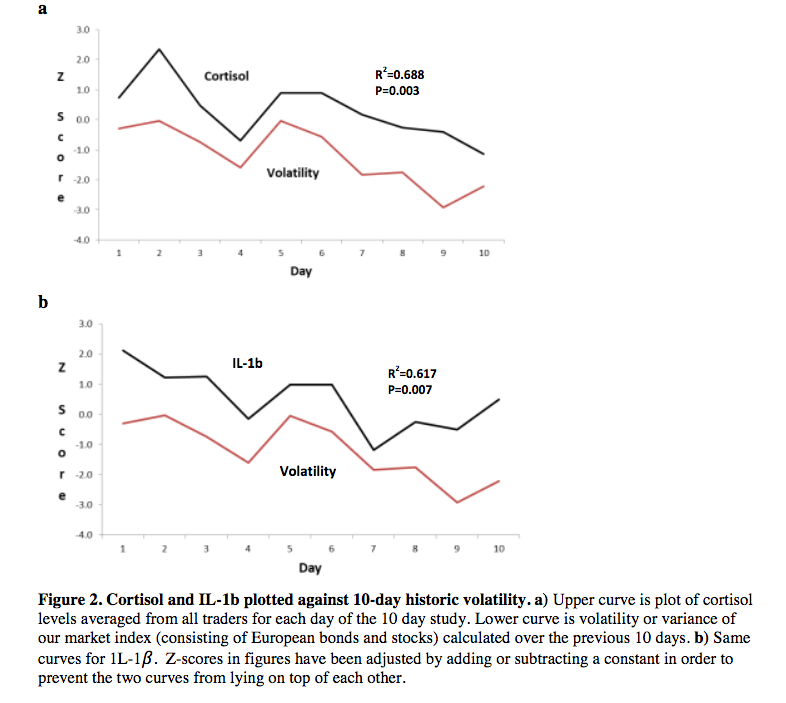

Simultaneously, the research team referenced an index of equity and bond volatility to monitor fluctuations in market stability. Not surprisingly, they observed a strong link between market volatility and elevated cortisol, the main stress hormone.

During the two-week study period, the volatility index dropped approximately 18%. The traders’ average daily cortisol levels also dropped by a strikingly similar 19%.

Participants’ mean cortisol levels at each daily sampling point correlated “significantly and positively” with price changes in Eurostoxx and Bunds, the two main European stock markets. Changes in cortisol lagged behind market fluctuations by approximately one hour (coef. = 0.182, Adj 𝑅2 = 0.86, 𝑝 = 0.02, 𝑁 = 30).

“This finding agrees with existing research suggesting that the halflife of an episodic increase in cortisol is approximately 66 minutes,” the authors noted.

The discovery that changes in the market correlate with elevated stress among finance professionals is not on its own a new finding. Neuroscientist John Coates, PhD––one of the paper’s authors––showed in a prior study that traders experienced a 68% jump in mean daily cortisol levels as market volatility increased over an 8-day period (Coates, J & Herbert, J. 2008. PNAS. 105 (16): 6167-6172).

Like cortisol, the traders’ IL-1𝛽 production closely mirrored changes in the volatility index.

Coates, a former research fellow at the University of Cambridge, was himself a Wall Street trader at one point in his life. After earning his doctorate, Coates worked for companies including Goldman Sachs, and ran a trading desk for Deutsche Bank in New York.

After observing the behavior of financial professionals on the trading floor, Coates grew interested in researching the biology of risk taking, gut feelings, and stress.

His earlier investigations centered on stress and the activation of the endocrine system in individuals engaging in financially risky behavior.

Information Induces Inflammation

Coates and his colleagues, based at Cambridge University, identified that the immune system also plays a key role in risk taking. They found that exposure to large amounts of financial information almost immediately triggered powerful endocrine and inflammatory reactions in the body.

Coates’ 2018 Biorxiv paper posits that high-volatility financial crises offer a unique opportunity to examine the biological response to information overload. In volatile markets, traders endure a constant flow of unsettling status reports and news releases about seesawing securities prices.

“When traders and asset managers around the world read news feeds and observe price changes they become immersed in an environment of nonstop information and surprise, and their physiology tracks it in sympathy,” Coates and colleagues reported.

When market volatility soared, the traders’ physiology resembled a typical chronic stress condition. Market stabilization brought a decrease in information exposure and subsequently provided a greater sense of certainty. In turn, participants’ immune systems began returning to a more normal state.

One of the main immune markers they looked at was the pro-inflammatory molecule IL-1𝛽. Coates’ research team observed that, like cortisol, the traders’ IL-1𝛽 production closely mirrored changes in the volatility index. Elevated IL-1𝛽 secretion is associated with the presence of inflammatory disease (Kaneko, N et al. 2019. Inflamm Regener. 39(12)).

When the market volatility index fell by 18%, daily average IL-1𝛽 levels among the traders also decreased by 18%. Within-day IL-1𝛽 concentrations shifted in tandem with both market volatility and an index measuring the traders’ physiological arousal. These changes resembled the co-occurring shifts in cortisol levels seen throughout the study.

N. Z. Xie, L. Page, D. A. Granger, J. M. Coates

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/473157

IL-1𝛽 as First Responder

It’s not hard to imagine that a stressful experience would kickstart an inflammatory response in the body. But in the London study, a different pattern emerged.

The data revealed temporal interactions among cortisol, IL-1𝛽, and three other inflammatory cytokines. The traders’ IL-1𝛽 levels significantly predicted not only cortisol, but also IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-𝛼 concentrations.

IL-1𝛽, the authors explain, was acting as a “first responder,” initiating a cascade of subsequent immunological and endocrine reactions. This finding echoes earlier studies defining IL-1𝛽 as an upstream signaling molecule that sets off a series of other stress and inflammatory responses in the body.

Over time, chronic stress and low-grade systemic inflammation can produce a condition called “sickness behavior.” Normally a defense against physical pathogens, the Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine defines sickness behavior as a “motivational state responsible for reorganizing an ill individual’s perceptions and actions to enable better coping with infection.”

The data revealed temporal interactions among cortisol, IL-1𝛽, and three other inflammatory cytokines: IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-𝛼.

It includes adaptive traits like fever, appetite loss, fatigue, social withdrawal, reduced pleasure-seeking, a heightened sense of fear and–if prolonged–depression. In other words, it’s that sick feeling that tells us something is really wrong.

Sickness behavior makes sense when a person’s immune system is focused on fighting disease. But what happens when the members of an entire professional group all behave like they’re ill at the same time?

Sickness Behavior: A Market Force?

One element of the classic sickness response is a decrease in risky behavior. Coates’ group believes that long bouts of systemic inflammation and chronic stress––like what traders experience during periods of high market volatility ––might instill a collective sense of risk aversion throughout the financial community.

“Given the high correlations we have found in this and our previous study, we suggest that both cortisol and IL-1β rose during the Debt Crisis, perhaps substantially, and for an extended period of time,” they write.

While it is not possible to retroactively measure traders’ cytokine levels as the Debt Crisis unfolded, the researchers believe that chronic cytokine elevation “would have brought risk-aversion to the financial community and may well have exacerbated the market sell-off.”

Coates and colleagues believe stress physiology has powerful effects on the stability of entire financial marketplaces.

“Our guiding hypothesis has been that physiological changes occurring in the financial community shift risk preferences pro-cyclically,” they write. This phenomenon “caus[es] investors to take too much risk on the upside, pushing a bull market into a bubble, and too little on the downside, driving a bear market into a crash.”

By the time the Cambridge researchers reached the trading floor to study their cohort of traders, the crisis in Europe was abating, and the traders’ physiology may have been returning to a more “normal” state.

The reduced stress and inflammatory responses “could have released the brake on their risk-taking and they, along with the wider financial community, felt emboldened to start buying in the credit markets.”

“Our findings therefore offer the beginnings of an understanding of what could be called the biochemistry of risk-on, and more generally of the shifting risk preferences that destabilize markets.”

They also point out that inflammation-induced risk-aversion “could well provide an explanation for the observation that stock markets under-perform during the time of year when seasonal affective disorder occurs.”

October––a notorious month for stock market crashes––maps with the time of year when, in late autumn and early winter, the body’s levels of circulating cytokines IL-1β, TNF-𝛼 and IL-6 naturally tend to increase.

Defining Financial Wellness

There were a number of limitations to the London study, including its small sample size, short duration, and inclusion of male participants only. But the findings do shed light on the flurry of biological responses initiated by uncertain financial situations.

Money-related stress, of course, isn’t limited to those who work in financial services. If hedge fund traders, who are generally well-off even in the worst of times, show wild cytokine swings in response to market shifts, it is reasonable to extrapolate that these physiological responses are even more intense in people who are struggling to get by economically.

For the millions of people who’ve endured the death of loved ones, job loss, staggering medical bills, and food or housing insecurity over the past year, these endocrine and immune system changes are, no doubt, extreme.

If hedge fund traders, who are generally well-off even in the worst of times, show wild cytokine swings in response to market shifts, it is reasonable to extrapolate that these physiological responses are even more intense in people who are struggling to get by economically.

Coates and colleagues are not the only researchers to show that personal financial stress has physical ramifications. Findings from a 2016 study by John Sturgeon and colleagues at Stanford University showed that financial stress influences inflammation. Participants exposed to major financial stressors exhibited higher concentrations of inflammatory markers IL-6 and C-reactive protein, which correlated with greater levels of self-reported psychological distress and lower levels of psychological wellbeing (Sturgeon, J et al. 2016. Psychosom Med. 78(2): 134-43).

More recently, a 2020 analysis looked at financial stressors within the context of the COVID-19 crisis.

Over 3,000 participants were surveyed about their fears related specifically to the coronavirus. Concerns about financial burdens stemming from the pandemic were as troublesome as fears about contracting the virus itself. Respondents worried less about dying from COVID-19, than about being confronted with poverty.

Interestingly, female participants generally reported higher overall COVID-19-related worries than males, with one exception: when it came to financial concerns, men and women reported comparable stress levels (Barzilay, R et al. 2020. Trans Psych. 10(291)).

It’s not yet clear how financial stressors connected to COVID might be affecting our immune health. But if the existing research offers any indication, the pandemic is challenging our immune systems in more ways than we realize.

END