Food insecurity is an enormous and multifaceted problem in the United States. Across the nation, tens of thousands of hunger relief agencies play a critical role in nourishing their communities, by providing food for millions of people.

In an ideal world, everyone would have access to balanced meals that meet their individual health and nutritional needs. Unfortunately, this is not the case for millions of Americans.

According to Feeding America, one of the country’s largest anti-hunger organizations, at least 60 million Americans visited large regional food banks, smaller local food pantries, or other food assistance programs in 2020 alone.

The number of people facing food insecurity surged during the first year of the Covid pandemic, and it has not let up since then. The need for food aid is growing at historic rates.

Two and a half years after the onset of Covid-19, 80% of food banks continue to report either an increase in or steady demand for emergency food services, according to a recent report from Feeding America. The organization supports a vast network of more than 200 food banks and 60,000 pantries across the country.

Unprecedented Demand

Historically high inflation, combined with significant jumps in food prices over the last year, are only exacerbating longstanding food access issues that predate the pandemic.

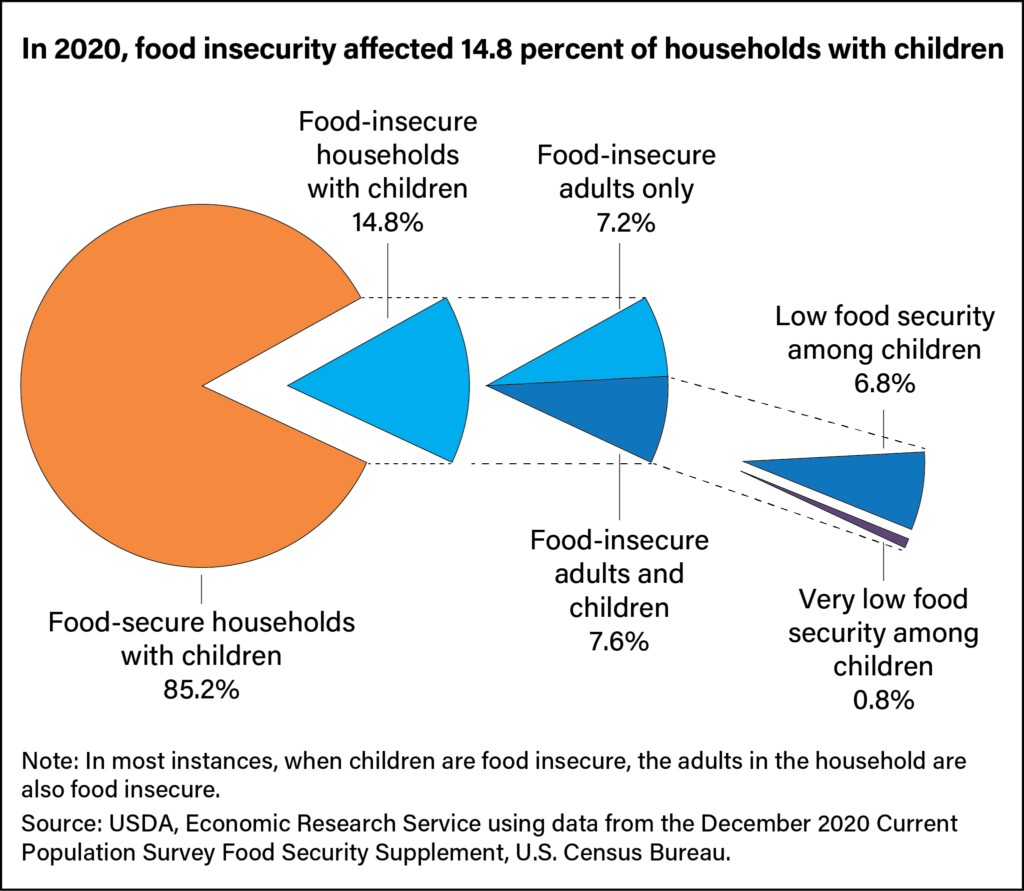

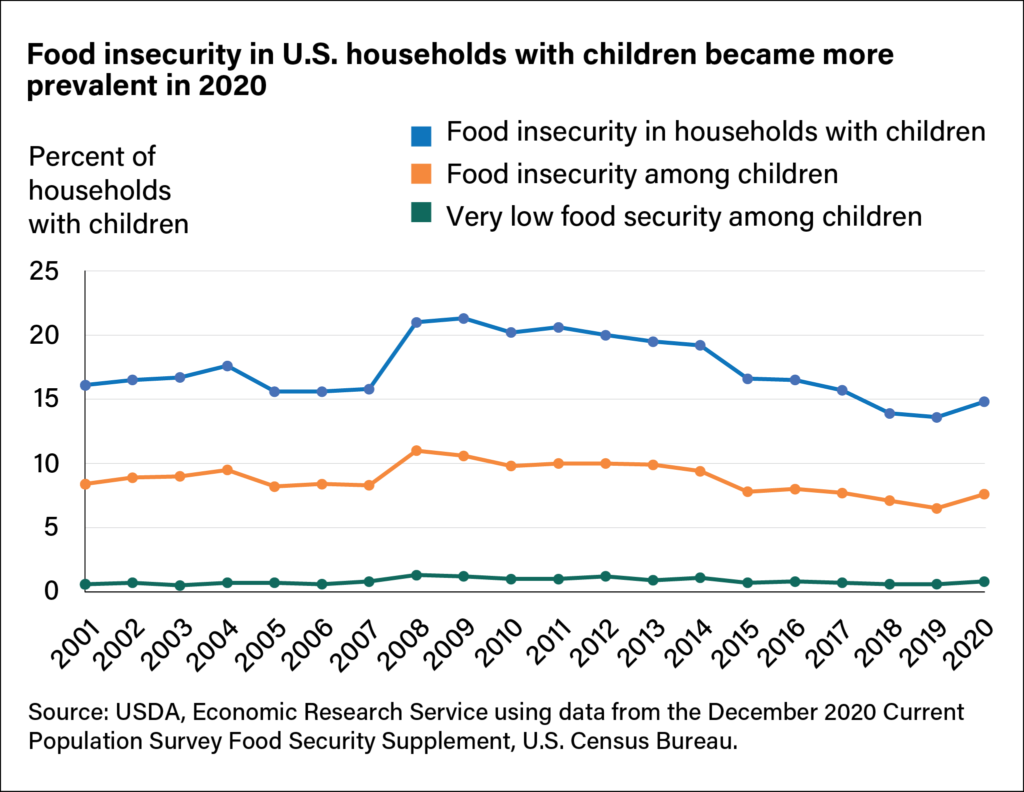

According to data from the US Department of Agriculture, the percentage of food-insecure households increased to 14.8% in 2020, up from 13.6% in 2019. This increase disrupted a decade-long downward trend.

I witness this surging demand on a regular basis at North Valley Food Bank, the food pantry where I work in rural Montana. In 2022, overall visits to my food pantry increased by a massive 81%, compared to 2021 — and that was after the spike in demand we experienced in 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the first Covid wave. This year, we’ve served hundreds of first-time visitors who never needed to use a food pantry prior to 2022.

This situation is not unique to our community. All across the country, food banks are reporting unprecedented levels of need. Some, like the Blue Ridge Area Food Bank, which serves families in the Monacan Indian Nation in central Virginia, are serving ten times more people than they were prior to the pandemic.

Feeding America’s 2021 annual report states that nationwide, food banks and related programs are serving 55% more people than they were before Covid.

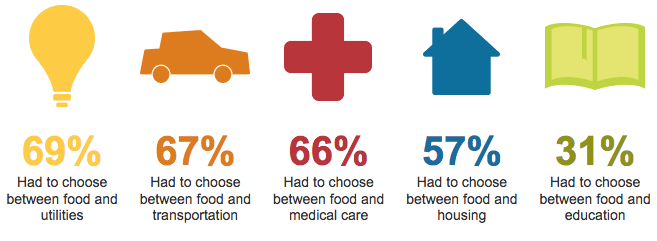

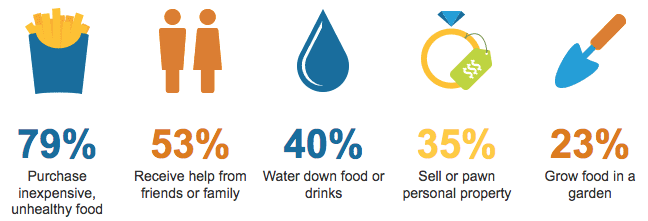

Many people who lack consistent access to adequate food also lack other vital resources, including healthcare, housing, living wages, transportation, and social supports. Poor nutrition is a known risk factor for numerous chronic diseases. Consequently, people living in households that depend on food aid agencies are at elevated risk of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and other diet-related conditions.

Individuals who rely on emergency food programs are unlikely to get all the nutrients they need through diet alone. Healthy food can be especially hard to find in low-income neighborhoods, and in rural areas where grocery stores may be few and far between.

What if people seeking food assistance could also pick up vitamins, minerals, and other types of dietary supplements while receiving groceries from food pantries and other food aid agencies?

If handled properly, this could be an excellent way to help people fill their nutritional gaps.

The question of whether to distribute supplements is a very real and practical one for people working in the field of food relief. Unfortunately, there are no uniform national guidelines on this issue, and the reality is very few food banks and pantries distribute supplements.

HER Nutrition Guidelines

Given the high prevalence of chronic disease among food bank users, there have been several important initiatives to encourage good nutrition within food aid programs. But at best, they have been ambivalent about inclusion of nutritional supplements.

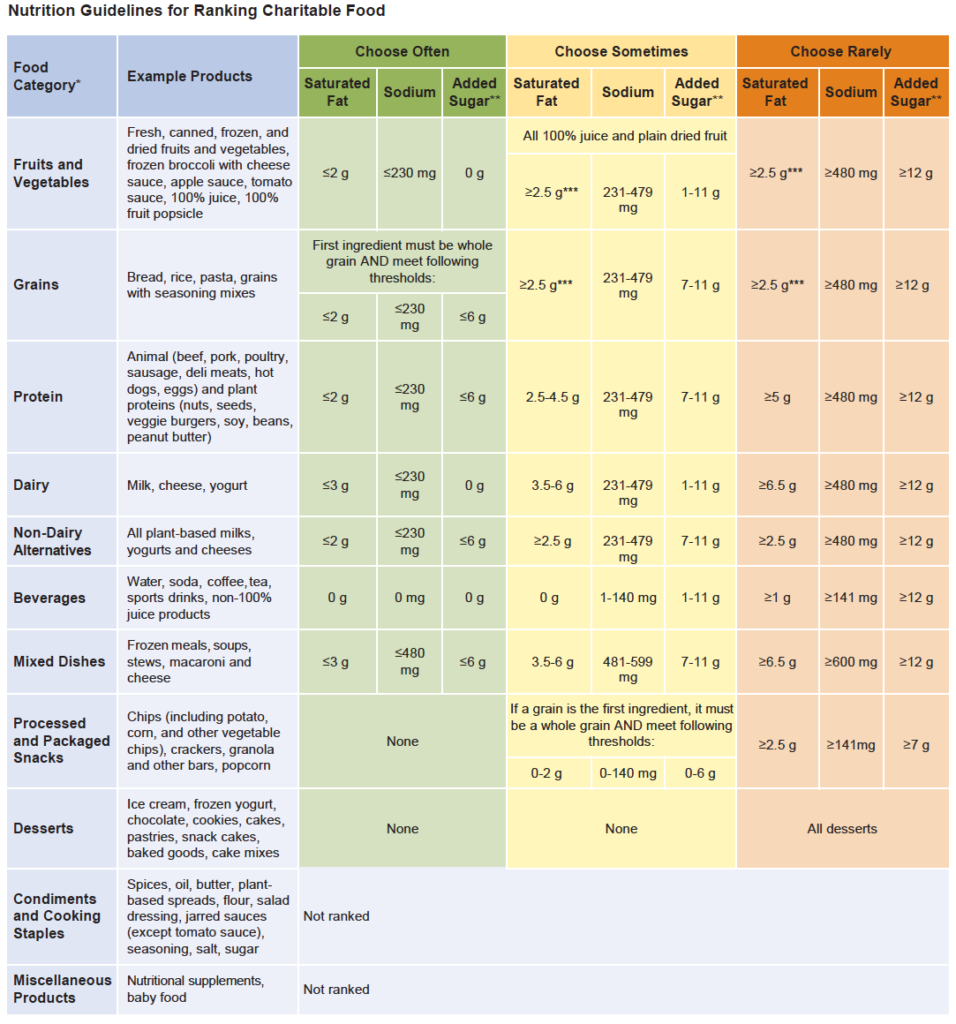

In 2019, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation called Healthy Eating Research (HER) convened a panel of experts in the nutrition, food policy and charitable food distribution fields. The group issued a final report in March of 2020 entitled, Healthy Eating Research Nutrition Guidelines for the Charitable Food System.

The report contains evidence-based nutrition recommendations tailored specifically to the needs and capacities of food assistance programs. Its authors aim “to improve the quality of foods in food banks and pantries in order to increase access to and promote healthier food choices.”

The HER recommendations draw from various nutrition ranking systems created for use within nonprofit, government, and private sectors. They also incorporate federal guidance from the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the Food and Drug Administration’s food labeling rules and regulations.

“Many items moving through the charitable food system are shelf-stable, highly processed foods that tend to be high in saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars,” the report acknowledges. Therefore, the HER nutrition guidelines focus primarily on limiting fat, salt and sugar content.

The HER system is designed to help food banks—and the people who visit them– evaluate the nutritional quality of the products they distribute. Based on their ingredients, food products fall into one of three tiers: “Choose Often,” “Choose Sometimes,” or “Choose Rarely.”

“Not ranked”

The HER guidelines also address a small category of nutritional products that don’t receive a formal ranking. “Food banks and food pantries often receive miscellaneous items, such as protein powders, nutritional supplements, and baby food,” the authors state. “These items are not ranked as they are considered necessary only for specific populations or when treating specific disease states.”

The report goes on to say, “It is important to note that these miscellaneous products are by and large not appropriate for use by the general population. Rather, they should be reserved for clients with specific nutritional needs or conditions.”

Though the HER guidelines do not categorically dismiss these products, they do not rank or recommend them.

In my experience, it is not unusual for North Valley Food Bank and other programs like ours, to receive donated supplements of all kinds. The products come to us from food retailers and distributors, food drive collections, individual donors, and other channels.

To Distribute or Discard?

When dietary supplements arrive at our facility, we’re faced with the hard question of what to do with them. Most food banks and pantries look to large national organizations like Feeding America for guidance around product safety and distribution.

In general, Feeding America follows food handling rules set forth by ServSafe. Administered by the National Restaurant Association, ServSafe is the gold standard food and beverage safety training program for restaurant and other food service employees. In 2014, Feeding America partnered with ServSafe to create a Food Handler Guide for Food Banking. It provides extensive instruction on receiving, handling, storing, and assessing the quality of products food banks acquire either through purchase or donation.

The guide does address the safe handling of certain kinds of medication. One brief section explains how to assess over-the-counter (OTC) medication safety, and instructs food handlers to check with their individual programs to determine whether OTC products are permitted for distribution. It also states that potentially dangerous products containing ephedrine or pseudoephedrine should never be distributed at any program site.

But this guide includes no mention of any type of dietary supplement.

In the absence of rules specifically addressing supplements, each food aid organization must determine for itself how to handle these products. In my region, for instance, the Montana Food Bank Network (MFBN) has its own internal nutrition policy. The policy states that MFBN “does not accept or distribute OTC medications, alcohol, energy drinks, dietary supplements, vitamins, baby food, or pet food.”

Unmet Nutritional Needs

Community food pantries like mine usually follow the nutrition policies set forth by our regional food banks. This means that at my program, when we receive donations of high-quality dietary supplements, we cannot distribute them to customers. That remains true even when the donated products are manufacturer sealed, undamaged, and well-dated.

Sadly, this is a lost opportunity. Many individuals are deficient in certain vitamins and minerals, and they rely on dietary supplements to stay healthy. But the costs of good quality multivitamins, as well as more specific supplements, can add up quickly. People seeking food assistance are less likely to have extra cash to spend on “luxury” items like supplements.

Federal food programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) should, in theory, act as the first lines of defense against malnutrition for low-income Americans. However, the benefits that qualifying households receive don’t necessarily address all the dietary needs of people living in food-insecure households.

The average benefits that SNAP participants receive equal around $4 daily per person, or approximately $1.40 per meal. That doesn’t go very far given today’s food prices—especially for healthy foods. It’s challenging for many households to meet each family member’s food needs on just $4/day, particularly in the current economy.

To complicate matters further, SNAP and WIC recipients cannot use their benefits to purchase vitamins or other supplements. These “non-food” items are explicitly ineligible for coverage under SNAP and WIC. Recipients can, however, use their benefits to pay for snack foods which are often laden with sugar, salt, unhealthy fats, and a host of colorings, preservatives, and other chemicals with potentially negative impact on health. They can also use SNAP/WIC for “non-alcoholic beverages” including sodas and other soft drinks.

The net result is that individuals and families who struggle to meet their nutritional needs, and who could potentially benefit from dietary supplements, must often go without them.

Safety Concerns

Supplements aren’t a magical cure-all for the myriad health conditions that food bank customers live with. And there are a number of legitimate safety concerns regarding supplement use.

Some argue that because we should be able to derive all essential nutrients directly from food sources, there isn’t actually a valid need for dietary supplements. Others suggest that using supplements encourages people to skip meals.

In my experience, those who access food assistance programs often skip meals anyways — and not by choice. So that argument is moot.

There are sometimes issues with supplement quality and purity. Food pantries like mine often receive donated products that are at or nearing their “best by” dates. Depending on the product type, a supplement that’s past its “use by” date may be less potent or less effective than it was when initially packaged. People with compromised health might not want to take a chance on an outdated product. Typically, food bank staff aren’t qualified to make recommendations about health or medical products to their clients.

Additional concerns like purposeful or accidental adulterations, misleading marketing, and exaggerated product claims also merit consideration. Indeed, for these reasons and others, the FDA as well as several major medical organizations including the American Medical Association have gone so far as to actively discourage the clinical use of dietary supplements.

Proper Disposal

But if supplements can’t be safely distributed at food banks, is throwing them away really an acceptable solution?

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) warns Americans against the improper disposal of supplements, vitamins, OTC medications, and prescription drugs.

“Some medicines, vitamins and other supplements poured down the drain or flushed down the toilet may pass through wastewater treatment plants. They may enter lakes, rivers and streams which are often used as sources for community drinking water supplies. Wastewater plants are generally not equipped to routinely remove medicines and supplements.”

Instead of dumping them, the Agency outlines a multi-step process to appropriately label and dispose of unwanted medications and supplements. Proper disposal involves mixing products with “undesirable substances,” packaging them inside disposable containers, and placing them in the trash as close to garbage pickup time as possible.

In the trenches, guidelines like these just create more toil for the people working in understaffed yet overwhelmed food banks and pantries.

Dietary supplements create a real conundrum for food aid agencies. On the one hand we see their potential for helping people improve overall nutritional status, while on the other we are aware of the potential problems. Currently, there are no easy answers.

Seeking Creative Solutions

We’re also hopeful that the topic of food insecurity is receiving some formal attention at the federal level. In September 2022, the Biden administration hosted the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health. It was the first time in over half a century that the event took place.

The initiative’s stated goal is to “End hunger and increase healthy eating and physical activity by 2030, so that fewer Americans experience diet-related diseases like diabetes, obesity, and hypertension.” The conference included hundreds of conversations, listening sessions and surveys of food-insecure individuals from across the US.

The strategy that emerged from the White House conference includes several promising objectives, including a project aimed at “Integrating nutrition and health, including by working with Congress to pilot coverage of medically tailored meals in Medicare; testing Medicaid coverage of nutrition education and other nutrition supports…and expanding Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries’ access to nutrition and obesity counseling.”

The Biden-Harris plan also projects an expansion of “incentives for fruits and vegetables in SNAP; facilitating sodium reduction in the food supply by issuing longer-term, voluntary sodium targets for industry; and assessing additional steps to reduce added sugar consumption.”

But in keeping with a decades-long policy of exluding supplements from federal programs, the new initiative makes no mention of them other than to state that, “FTC (Federal Trade Commission) has indicated that it will pursue targeted law enforcement actions to prevent the deceptive advertising of foods and dietary supplements, including deceptive advertising that might be targeted to youth.”

We’ll be watching closely as the White House lays out its vision for ending hunger and reducing diet-related chronic disease in the months and years to come. Whether nutritional supplements will eventually have a place in policies that aim to alleviate hunger and improve nutrition remains to be seen. At the moment, that seems doubtful.

Game Changers

It is painfully clear here in northern Montana that winter is by far the most challenging time of year for many families experiencing food insecurity. With more people now accessing our services than ever before, we’ve developed some creative strategies to help feed our community.

Through the MFBN, we participate in a regional program called Montana Hunters Against Hunger. This program allows hunters to donate legally and ethically harvested deer, elk, antelope and other wild game to our food pantry. We then process and package the meat on site and distribute it directly to our pantry clients. It provides our clients with an incredible additional source of nutritious, local, and cost-free lean protein during the Fall and Winter months.

Elsewhere in the country, other organizations run similar wild game donation programs. The Anne Arundel Economic Development Corporation’s Hunt Down Hunger venison program benefits a local food bank in the state of Maryland.

END