A phase 3 study of psychotherapy with the addition of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) shows that inclusion of this psychedelic compound can markedly reduce the symptom burden of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and improve quality of life, compared with psychotherapy plus a placebo.

The study, hailed as a landmark on the long road toward legitimizing medical use of psychedelic drugs, was recently published in the journal Nature Medicine.

The trial involved 90 people with severe PTSD, including combat veterans, witnesses to mass shootings, first responders, and victims of sexual assault, domestic violence, or childhood trauma. Many had long histories of suicidality, alcohol, or substance abuse.

Jennifer Mitchell, PhD, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Francisco, and lead author of the study, coordinated a team of 80 therapists in the US, Canada, and Israel, all of whom are trained in MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. Mitchell is among a vanguard of researchers working with drugs like MDMA and psilocybin.

The study was based on strict FDA-approved protocols. In the initial phase, the patients had preparatory sessions with two therapists, after which they were assigned to participate in three eight-hour sessions, spaced one month apart, during which they were given either MDMA or inactive placebo.

Neither participants nor therapists knew to which arm the patients were assigned, although given the consciousness shifting effects of MDMA, most were quickly able to figure it out. The issue of blinding for studies of drugs known to alter perception is a major challenge for the entire field of psychedelic research.

Two months after the final sessions, 67% of those in the MDMA-assisted group no longer met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, compared with just 32% in the psychotherapy-plus-placebo group. Those who got MDMA also had a significantly greater reduction in symptom severity compared with those assigned to the placebo (Mitchell JM, et al. Nature Medicine. 2021).

There were no serious adverse effects associated with MDMA, though some participants temporarily experienced mild symptoms like nausea and loss of appetite.

Breakthrough Status

This is the first phase 3 study of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, and it puts the modality several steps closer to FDA approval as a recognized treatment for PTSD.

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Research (MAPS), a non-profit organization at the epicenter of the current psychedelic renaissance, sponsored Dr. Mitchell’s trial, as well as a second confirmatory study expected to finish later this year.

Preliminary data from an earlier MAPS-sponsored study of 107 PTSD patients showed that 23% of those assigned to psychotherapy alone without MDMA no longer met the PTSD criteria; among those getting psychotherapy plus MDMA that increased to 56%. At 12 months after the final sessions, two-thirds no longer had PTSD.

The term “psychedelic” means simply “mind manifesting.” As early psychedelic pioneer Dr. Stanislav Grof put it: “Psychedelics are to the study of the mind what the microscope is to biology and the telescope is to astronomy.”

In a recent TED talk, MAPS founder Rick Doblin, PhD, noted that by 2017, the available data was strong enough for the FDA to designate MDMA-assisted psychotherapy as a “breakthrough therapy,” meaning a treatment for a serious disorder that shows substantial benefits beyond existing approved treatments, and that warrants expedited development.

FDA has also granted breakthrough status to Ketamine for treatment of severe refractory depression.

Assuming the second MAPS phase 3 trial corroborates the first, the FDA could approve MDMA psychotherapy as a prescription-based PTSD treatment by the year’s end, setting the stage for far broader clinical use of this drug, which was first synthesized and characterized by Merck researchers back in 1912.

The Psychedelic Renaissance

It is no secret that a lot of people are interested in psychedelics these days, both for medical uses and for personal spiritual or recreational exploration. Odds are good that at least a few of your patients have already experimented with substances like LSD, MDMA, ketamine, Psilocybin mushrooms, Peyote (mescalin), or the complex mixture of psychotropic botanicals called Ayahuasca.

Within the clinical context, major medical centers around the globe have established psychedelic research programs, including New York University, University of California-Berkeley, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Imperial College London, Be’er Yaakov Hospital, Israel, and the world’s largest at Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.

In addition to MDMA and ketamine, researchers are looking at the therapeutic potential of Psilocybin, LSD, Mescaline, and Ibogaine—a hallucinogen derived from the roots and bark of the Tabernanthe iboga shrub indigenous to Central Africa.

There are hundreds of chemical compounds—naturally occurring and synthetic—that can induce non-ordinary states of consciousness. While each has unique biochemical properties, there are several common features, the main one being a high affinity for serotonin receptors.

Beyond PTSD, they’re studying psychedelics as treatments for major depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias, eating disorders, anxiety, end-of-life issues, panic, alcoholism, and substance abuse. Outside the medical sphere, many people are exploring the psychedelic experiences as a doorway to spiritual guidance, self-transformation, and getting ‘unstuck.’ Author Michael Pollan documented this newfound public interest and the emerging science around psychedelics in his 2018 book, How to Change Your Mind.

In 2020, there were 17 major psychedelic trials published in peer-reviewed journals, up from 3 in 2010. Twelve are underway this year, so far.

That’s still a far cry from the thousands published in the 1950s and 60s, before the federal government criminalized all psychedelic drugs in 1970 and essentially banned research on them. But that did not extinguish scientific, medical, or public interest; it merely pushed it underground where it has been quietly gathering momentum for decades.

A Paradigm Shift

The recent surge reflects both a widespread hunger for new therapeutic approaches, and a recognition of the limitations of conventional treatment modalities.

“The blush is off the rose regarding prescription psychiatric medicines,” says Scott Shannon, MD, an integrative psychiatrist based in Fort Collins, CO, and founder of the Psychedelic Research and Training Institute, an organization committed to training physicians and other medical practitioners in the clinical use of psychedelics.

“Thirty-five years ago, the chemical imbalance theory of mental illness held sway, especially in depression, and the mainstay drugs we have were outgrowths of that. In that era, there was a lot of excitement and expectation that this was going to transform mental healthcare. While there were certainly advances, in the main, psychiatry based on SSRIs, MAOIs, sedatives and antipsychotic drugs has fallen far short of the hoped-for dream,” said Shannon at the 2020 Scripps Natural Supplements conference.

Overall, the track record for standard psychiatric drugs is spotty at best. Consider that:

- Suicidality among adults has increased dramatically over the last decades, and is now at the highest it has been since the height of World War II, despite widespread use of antidepressants.

- Prevalence of pediatric major depression rose from 8.6% to 13% from 2015 to 2020.

- Deaths related to despair, alcoholism, addiction, and violence are on the rise, and US life expectancy has fallen for the last 3 years in a row.

- Between 20% and 50% of all people treated for major depression develop resistance to the drugs over time.

- More than half (54%) of patients who stop antidepressants experience withdrawal symptoms, often severe.

Further, many psychiatric medications blunt affect and libido. Others, including the SSRIs, benzodiazepines, tricyclic antidepressants, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors can cause withdrawal problems.

“When you begin to acknowledge the drawbacks, you’re on the edge of a paradigm shift,” says Shannon.

“Even though the ship is burning and about to sink, few are going to jump off that boat unless they see something else to jump to. I believe pyschedelics are that place to land. They represent the next transformative development of mental healthcare,” says Shannon, who was among the investigators in the new MDMA trial.

Like Doblin, and many other advocates, he believes psychedelics offer new and better alternatives for treating psychological, emotional, and behavioral disorders. Given what we now know about the impact of psychological states and behavior patterns on overall physical health, this has ramifications well beyond the narrow bounds of psychiatry.

Manifesting the Mind

The term “psychedelic” means simply “mind manifesting” (from the Greek psyche, “soul or mind” and deloun, “to show or manifest”), the core idea being that by altering perception and consciousness, these substances reveal to the user the nature and potential of his or her own consciousness.

As early psychedelic pioneer Dr. Stanislav Grof put it: “Psychedelics are to the study of the mind what the microscope is to biology and the telescope is to astronomy.”

There are hundreds of chemical compounds—naturally occurring and synthetic—that can induce non-ordinary states of consciousness. While each has unique biochemical properties, there are several common features, the main one being a high affinity for serotonin receptors.

In the late 1990s, neuroscientists at the University Hospital Zurich applied positron emission tomography and other neuroimaging techniques to explore the biological effects of LSD, Psilocybin, Mescaline, and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), one of the key compounds found in Ayahuasca. They found striking similarities in how all of them affect the human brain. Strong activation of 5-HT2 receptors was a stand-out feature.

There is evidence that MDMA can raise levels of oxytocin and dopamine, which might explain how it came to be called Ecstasy in the dance club where it is a popular, albeit illegal, recreational drug.

Dr. Shannon does not consider MDMA and ketamine to be true “classical” psychedelics such as Peyote, Mescaline, or Ayahuasca, in the sense that they do not produce hallucinations, profound alterations of perception, or the sense of ego surrender that occurs with other “true” psychedelics.

“MDMA is an empathogen. It makes people feel safe, feel closer to others. It’s a heart opener that releases monoamines, neuropeptides, oxytocin and prolactin, which are bonding hormones,” he explained. But the protocols designed by MAPS for PTSD and depression follow the psychedelic psychotherapy model.

Dimming the DMN

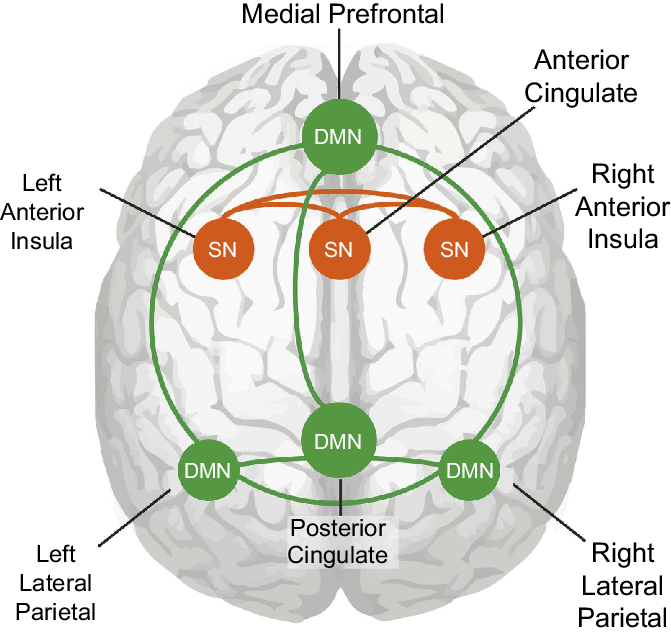

Hallucinations or not, there’s a growing scientific consensus that the therapeutic utility of these drugs is in their ability to reduce activity of the so-called Default Mode Network (DMN), the brain’s baseline resting state.

The DMN gives someone his or her ordinary sense of “self.” It’s a habituated set of running, repetitive thoughts and emotions. It is what generates our personal stories about identity, history, sense of self-worth (or lack thereof), and place in the world. “It’s where the inner narrative lives. The ego is tied up in it. It’s where all the biases live,” Shannon explains. “It’s the rumination, the worry, the preoccupations, the self-importance.”

Physiologically, the DMN is a set of coordinated brain functions involving the posterior cingulate gyrus, precuneus, medial prefrontal cortex, and temporal cortex. It runs more or less constantly, and actually consumes the majority of brain energy.

Tasks that require focused attention—solving a math problem for example—shift the brain’s activity out of the DMN and into the present situation. Meditation, practiced regularly, can do the same. So can psychedelic drugs, and they do it rather quickly.

“It’s not the drug — it’s the therapy enhanced by the drug,” that makes the difference in peoples’ lives.

Rick Doblin, PhD, Founder, Multidisciplinary Association for Pyschedelic Research

The therapeutic value of these substances is in their ability to move a person’s consciousness out of its usual loops which, in many people—especially those with depression or PTSD—are full of negative messages that predispose to ill health.

As Robin Carhart-Harris, head of the Imperial College London’s Psychedelic Research Group, wryly pointed out: When you are on LSD you are not ruminating about how mean that guy was at the coffee counter.

“When activity is reduced in the DMN, the ego as we know it shifts from the foreground to the background and we see that it is just part of a larger field of awareness,” says MAPS founder Rick Doblin. Most people find this experience extremely comforting, inspiring, and transformative.

After decades of work in trauma healing, Doblin has concluded that the PTSD brain is different from the non-PTSD brain. “It is characterized by a hyperactive amygdala where we process fear, reduced activity in prefrontal cortex which controls logical thinking, and reduced activity in the hippocampus where we have memory in long term storage.”

MDMA, he says, reverses these changes: it reduces activity in amygdala, increases activity in frontal cortex, and increases connectivity between amygdala and hippocampus. In aggregate, these changes permit someone to access memories of trauma but from a very different vantage point than his or her ordinary state.

The chemistry of psychedelic drugs is interesting, and their legendary embrace by the counterculture of the 1960s and 70s still fuels media sensationalism. But Doblin sees a danger in fixating too much on the substances. “It’s not the drug — it’s the therapy enhanced by the drug,” that makes the difference in peoples’ lives.

Ancient Tools, Modern Context

The desire to understand consciousness, and the impulse to use substances to alter it, are as old as humanity itself.

Ritual use of Psilocybin mushrooms, and Peyote or San Pedro cacti has a central place in community life among many indigenous South and Central American cultures, and among some Native American tribes here in the US.

This traditional ritual context appeals to many non-indigenous people. Earthy, ancient, and communal, the ceremonies represent an ideal remedy for our screen-mediated, socially isolated, punch-clock lives.

Prior to COVID, many people from the US, Europe, and other parts of the world were traveling to countries like Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, and Mexico where indigenous shamanic cultures are still well-rooted—although many are endangered.

One need not look too hard online to find dozens of psychedelic retreat centers, and travel packages for plant medicine healing journeys. As travel options reopen this summer, a resurgence is likely.

While some see psychedelics as a path back to a more rooted, rustic way of life, others see them as a hot business opportunity. The psychedelic renaissance has definitely grabbed the attention of Wall Street.

Consider COMPASS Pathways, a London-based drug company that has developed a standardized form of psilocybin. COMPASS pairs this with a proprietary approach to psychotherapy for major depression refractory to standard drug therapies.

The company filed an Initial Public Offering last Fall, valued at roughly $544 million. The stock rallied, quickly topping a valuation of $1.6 billion. While some analysts consider this a gross overvaluation, investor enthusiasm reflects a recognition that huge numbers of people with depression want alternatives to conventional antidepressants.

As the positive studies accumulate, public interest grows, and businesses forge ahead, regulators will feel increasing pressure to revise the laws, so practitioners can provide psychedelic therapies in safe, supervised, and well-controlled settings.

The COMPASS drug and its protocols were tested in two open label studies at the Imperial College London, with generally positive results. A phase 2b study is now underway, and the company says it is planning a phase 3 trial.

Dr. Carhartt Harris, who in 2016 published one of the landmark trials of psilocybin for depression, says of the drug: “I think it has the potential to revolutionize depression treatment, if not all of psychiatry.”

Here in the US, a company called Mindbloom has launched a network of branded retail clinics offering ketamine-assisted therapy. Promising “Breakthroughs that don’t break the bank,” Mindbloom offers 3-month programs for depression and anxiety consisting of 6 ketamine treatments, 2 psychiatric consultations, 3 guided sessions, and unlimited participation in “group integration,” for $89 per month.

Ketamine requires a physician’s prescription, and trained coaches guide patients along the protocol under physician supervision.

Mindbloom launched just prior to COVID, with a flagship clinic in lower Manhattan and plans for expansion throughout the country. Currently, the company offers its services via teleconsults in 11 states (NY, NJ, CA, TX, CO, AZ, VA, UT, FL, PA, NV).

MAPS itself has its eye on the marketplace. Several years ago, the group established a for-profit public benefit corporation to develop practitioner training programs in MDMA-assisted therapy, and ultimately to establish a network of clinics providing psychedelic-assisted modalities under the guidance of licensed physicians and therapists using the MAPS guidelines.

These are just a few of the many emerging psychedelic ventures. So far, though, the pharmaceutical giants have stayed away. Dr. Shannon thinks this is because psychedelics don’t fit with Big Pharma’s business model. “Psychedelics are about intermittent, even single use. The Big Pharma model is about daily, constant, indefinite use.”

Regulatory Challenges

The burgeoning psychedelic medicine movement still faces major regulatory hurdles.

With the exception of ketamine, which is an approved prescription drug, all other psychedelic agents—including MDMA—are illegal at the federal level, though some state and city governments have moved to decriminalize Psilocybin.

This means that outside of a research context, it is technically illegal for physicians and other healthcare professionals to administer them.

But as the positive studies accumulate, public interest grows, and businesses forge ahead, regulators will feel increasing pressure to revise the laws, so practitioners can provide psychedelic therapies in safe, supervised, and well-controlled settings.

The FDA does have a set of processes called Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS) through which the agency can require physicians and pharmacists who prescribe a particular drug or class of drugs to be specially certified in strategies to mitigate the risks associated with that drug. Some psychedelic advocates say REMS could be adapted to this context, by requiring practitioners who want to prescribe psychedelics to undergo training on their use and their risks.

This raises another set of questions: Given the long history of indigenous use, should the use of psychedelics be restricted only to MDs and NPs with drug prescribing rights? Is an MD with limited personal experience and a few weeks of training really better qualified in this context than a lay person who has spent 25 years apprenticing with shamans in Peru?

There’s also a question about the substances themselves. Will federal agencies decriminalize Psilocybin, Peyote, or Ayahuasca in their traditional forms as teas and decoctions? Or will they only permit synthetic, highly concentrated, ‘pharmaceuticalized’ forms?

The current psychedelic movement represents a broad spectrum of people and practices: At one end are the traditional communities using plants native to their regions much as they have for thousands of years. At the other end are the psychedelic entrepreneurs, and the Silicon Valley executives microdosing psilocybin to enhance their problem-solving.

Appropriate Use vs Appropriation

Psychedelics, even under medical supervision, are not appropriate for everyone. They are clearly contraindicated in people with schizophrenia, psychosis, bipolar disorder, or borderline personality disorder. Generally, guidelines for psychedelic therapies advise against it for people in poor overall health, especially those with cardiovascular disease.

Though rare, serious side effects can occur. Some people find psychedelic experiences to be deeply unsettling in a way that is not helpful or constructive.

There are also questions about use of psychedelics for patients with chemical dependencies or histories of addiction. Ibogaine generated excitement in some addiction treatment circles, because anecdotally it can short-circuit opiate or cocaine withdrawal and reduce drug cravings, leading to sustained abstinence. But the drug also raises the risk of cardiac arrhythmias.

Ibogaine has never been FDA approved, but a number of clinics outside the US offer ibogaine-assisted addiction recovery programs.

There’s a general consensus that psychedelics do not cause physical dependence. But psychological dependence or escapist preoccupation can occur, which is one of the many reasons why advocates say they should only be used in therapeutic or ritual settings under guidance of experienced practitioners.

The current psychedelic movement represents a broad spectrum of people and practices: At one end are the traditional communities using plants native to their regions much as they have for thousands of years. At the other end are the psychedelic entrepreneurs, and the Silicon Valley executives microdosing psilocybin to enhance their problem-solving.

Maya Shetreat, MD, is a neurologist who has also studied plant medicine extensively with a 4th generation shaman in Ecuador. Among her current projects is a Psychedelics for Mental Health online learning program to help people make sense of this field.

In an interview with Holistic Primary Care, Shetreat says she sees challenges at both ends of the spectrum.

Psychedelic tourism, in which people from wealthy countries go on healing quests to remote indigenous communities, can be fraught with economic inequities, cultural appropriation, and spiritual vanity. For some, a plant medicine ritual in a Quechua village is just another cool experience to talk about at parties.

Others are overly enthusiastic in their embrace of indigenous ways, grabbing snippets of cultures they have not yet invested the time to really understand. Still others see indigenous people and their medicines simply as commodities to be exploited.

“You have to come with real respect and commitment. You want to come with good intentions. You should do it only if you truly feel called.”

Maya Shetreat, MD

But exploitation can go both ways: psychedelic retreats represent business opportunities in areas where there are few. Inevitably, there are “shamans” leading retreats who are not qualified to do so, and who take advantage of naïve travelers.

At the other extreme, the impulse to standardize psychedelics so they fit into American healthcare settings or Wall Street business models, severs them from their deeper roots, and limits their potential as agents of transformation.

Shetreat, who has experience with a number of psychedelic plants, says an important aspect of these experiences is that they demand new modes of relationship.

“Part of what can happen is that old stories that you’ve told yourself for a long time, can be blasted apart. If you’re pretending, or doing things to enable some disempowering narrative for yourself or for someone else, that could be blasted apart. Then, you have to be willing to come forward honestly and decide how to move forward. It destroys things that are not authentic, and then you have to decide, ‘Is there a way to build this more authentically?’”

That, she says, requires humility and commitment. “There’s this longstanding spiritual tradition that when you consume these plants you are entering into a sacred relationship with the spirit of the plants. They are powerful. You know that because of the effects they have. You have to come with real respect and commitment. You want to come with good intentions. You should do it only if you truly feel called.”

END