Recent research on the connection between vitamin D deficiency and anemia paints a complex picture, with age, race and gender contributing to an entwined set of health risks that begin in childhood and may persist throughout adult life.

There is a strong correlation between low 25(OH)D serum levels and anemia; this has been reported in several studies of children and adults. In one study, vitamin D deficient children—defined as having serum levels ≤25 nmol/L—were three times more likely to be anemic than their vitamin D sufficient (>50 nmol/L) peers.

Conversely, anemic kids typically show lower mean vitamin D levels compared to their non-anemic peers (19.6 ± 13.3 vs. 24.0 ± 23.1 nmol/L).

Analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) suggest that dark-skinned children appear to have a protective advantage against anemia in the context of vitamin D deficiency.

Major Implications

Vitamin D deficiency has implications in the COVID context, especially in African American, Hispanic American, and Native American communities which have disproportionately higher rates of both vitamin D deficiency and COVID-19. Several studies show a strong association between deficiency and COVID risk, though a causal relationship has not been definitively proven.

This issue is the focus of a new advocacy campaign called “Get On My Level,” spearheaded by the Organic & Natural Health Association. The project promotes vitamin D home-testing in Black, Latin-American, and Native American communities, and the possibility that supplementation has potential to mitigate many of the race-related health disparities.

A Strong Association

A 2018 study published in the journal Nutrition analyzed the serum concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D), in nearly 1,000 Iranian children aged 9 to 12 years.

Researchers at Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, looked at the link between 25(OH)D and the risk of anemia in a sample of 937 pediatric patients (493 boys, 444 girls) (Nikooyeh, B & Neyestani, T. Nutrition. 2018; 47: 69-74).

Their findings strongly suggest an association between low 25(OH)D concentrations and anemia among the representative youth population, even after adjusting for sex, age, BMI, and hormone status. They defined vitamin D status according to circulating serum 25(OH)D: the children’s blood levels were considered sufficient at >50 nmol/L; insufficient at between 25 and 50 nmol/L; and deficient at ≤25 nmol/L.

Vitamin D deficiency (VDD), or hypovitaminosis D, is highly prevalent in the population of Iran, where up to 93% of children show suboptimal circulating serum 25(OH)D concentrations.

Overall, 13.3% of the children in the Iranian study were anemic. 64.2% and 28.1% of the subjects showed vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency, respectively.

After controlling for sex and BMI, the vitamin D deficient children were almost 3.45 times more likely to be anemic, compared with those who had sufficient vitamin D levels The increased risk of anemia became significant beginning at 25(OH)D concentrations of <44 nmol/L

Approximately 13% of the children had concurrent low levels of both hemoglobin (Hgb) and vitamin D. The prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in the anemic children was 96.8%, versus 91.6% in the non-anemic group (P = 0.046).

Overall, the vitamin D deficient kids were nearly three times more likely to be anemic than those who were vitamin D sufficient.

Modifiable Risk

The children with anemia had significantly lower mean 25(OH)D concentrations than non-anemic subjects (19.6 ± 13.3 vs. 24.0 ± 23.1 nmol/L; P = 0.003).

After controlling for sex and BMI, the vitamin D deficient children were almost 3.45 times more likely to be anemic, compared with those who had sufficient vitamin D levels (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.21–9.81). The increased risk of anemia became significant beginning at 25(OH)D concentrations of <44 nmol/L (17.6 ng/mL; odds ratio: 2.29; 95% CI, 1.07–4.91, P = 0.032).

“Vitamin D status may be a modifiable risk factor for anemia prevention,” the authors write.

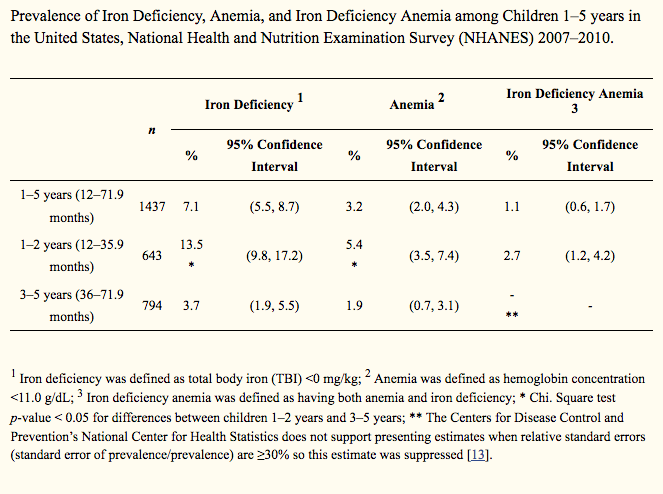

Iron deficiency (ID) is one of the most prevalent nutritional deficiencies worldwide, and it is the most common cause of anemia. Those at highest risk include infants and young children (Gupta, PM et al. Nutrients. 2016; 8(6): 330). Gender plays a role as well; both vitamin D and iron deficiencies occur more frequently among women than men.

A Complex Interaction

Scientists are working to elucidate the relationship between vitamin D and iron status––including determining exactly which nutrient exerts a stronger influence over the other (Malczewska-Lenczowska J, et al. Nutrients. 2018; 10(2): 167). Vitamin D receptors are present in the bone marrow, and it’s speculated that it could have a direct effect on red blood cell production.

Vitamin D receptors are present in the bone marrow, and it’s speculated that it could have a direct effect on red blood cell production.

While more work is warranted, Nikooyeh and colleagues stress that “gaps in the evidence for these associations should not debar taking the necessary actions.”

“The observed prevalence of hypovitaminosis D and anemia in the present study is noticeable and high enough to be considered a public health problem,” they argue. “The unfortunate truth is that globally, few active programs have succeeded in a remarkable reduction of anemia and/or hypovitaminosis D morbidity rates in the community. Many of the barriers that keep the current practices from progress are attributable to the failure to recognize the causes of deficiencies, lack of political commitment to control the problems, use of inadequate amounts of nutrients for interventions, and selection of vehicles for fortification that are not uniformly consumed in population subgroups.”

Race as Risk Factor

Besides age and gender, race is another major risk factor for both low vitamin D and anemia. Dark-skinned children appear to have a protective advantage against anemia in the context of vitamin D deficiency.

A 2014 study of otherwise healthy American children showed that, as in the Iranian group, an increased prevalence of vitamin D deficiency correlated with an increased risk of anemia. Analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data shows that the observed association was “independent of other confounding factors that could have contributed to anemia risk, namely, obesity, inflammation, socioeconomic status, and nutritional status, including vitamin B12, folic acid, and iron deficiencies” (Atkinson, M et al. J Pediatr. 2014; 164(1): 153-158.e1). But racial factors seem to play a major role.

The cross-sectional study included 10,410 children and adolescents aged 1–21 years and evaluated whether race was a modifying factor in the association between 25(OH)D deficiency and markers of anemia.

Lower vitamin D was associated with lower Hgb across racial groups. However, “the 25(OH)D levels at which the association becomes apparent differ by race, and were lower in black children.”

The link between low vitamin D status and low Hgb emerged in Black kids when 25(OH)D levels dropped below 11ng/mL. That same association appeared in White children at 25(OH)D levels greater than 20 ng/mL.

In essence, the findings suggest that at the same serum vitamin D levels of 20 ng/mL, a white child is more likely to manifest anemia than a black child, all other factors being equal.

Complex Interactions

Many other studies have indicated racial variations in the prevalence of iron and vitamin D deficiencies.

Researchers at the Mayo Clinic reviewed data from 197,974 patient samples collected between January 2010 to October 2018. They found “significant racial/ethnic differences in anemia and SF [serum ferritin] deficiency” among the analyzed samples (Gonzalez-Velez M, et al. Int J Lab Hematol. 2020; 42(4): 403-410).

26.8% of patients overall showed anemia, with a higher prevalence among American Indian/Alaskan Natives (42.9%) and African Americans (47.2%) (P < .001). The prevalence of serum ferritin was higher in Natives (1.4%) and African Americans (1.2%) and a lower in non-Hispanic whites (0.7%), Hispanics (0.6%), and Asians (0.3%).

“We believe that these differences may be explained by social determinants of health,” the study’s authors propose. “More research is needed regarding the causes of these differences and their clinical implications at a population level.”

END