Medical perspectives and public attitudes about post-menopausal hormone replacement have swung widely in the century since hormones were first described.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the term “hormone” was coined by Ernest Starling, a professor of physiology at University College London, UK. By 1926, Sir Charles R. Harington performed the first chemical synthesis of a hormone, thyroxine. This was followed by a landslide of discoveries and breakthroughs. By 1929, Edward Adelbert Doisy and his associates had isolated estrone—the first estrogen to be crystalized—from the follicular fluids and urine of pigs.

Sir Charles R. Harington performed the first chemical synthesis of a hormone, thyroxine. This was followed by a landslide of discoveries and breakthroughs. By 1929, Edward Adelbert Doisy and his associates had isolated estrone—the first estrogen to be crystalized—from the follicular fluids and urine of pigs.

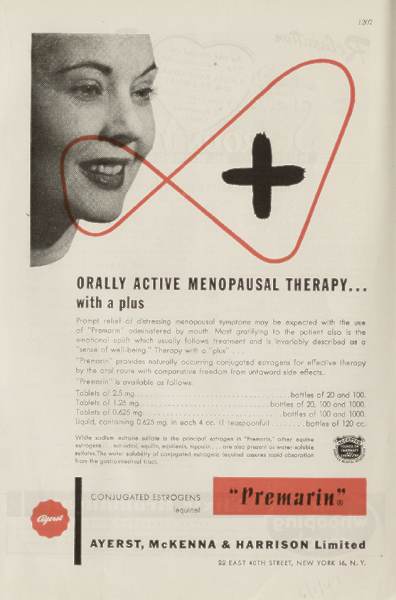

Not long after estrogen was crystallized, an estrogen complex extracted from placentas became commercially available. “Emmenin,” as it was called, was promoted for the treatment of painful menstrual cramps (dysmenorrhea), thus becoming first oral female sex hormone. Developed by a pharmaceutical company called Ayerst, McKennen and Harrison (later becoming Wyeth Pharmaceuticals), it was too expensive to manufacture on a mass scale.

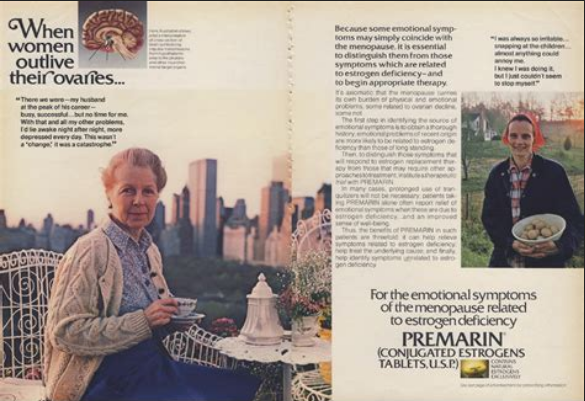

By 1938, researchers discovered they could collect similar substances from the urine of pregnant mares (PMU). “Premarin,” as the product was named, emerged in 1939.

Premarin, Pop Culture & Profits

“Premarin contained at least 10 estrogens, the dominant ones being estrone (50% to 60%) and equilin (22.5% to 32.5%) with less than 5% estradiol. Premarin hit the market in the United States in 1942,” according to a blog written by Drs. James Woods and Elizabeth Warner.

Fifty years later, Premarin was the number one prescribed drug in the US, topping out at more than $2 billion by 2001.

How did a drug originally indicated for severe menstrual cramps earn Wyeth more money in global sales than the entire gross domestic product (GDP) of nearly half the countries in Africa?

Premarin crested on a surging tide of drug company research and marketing, which met a popular culture obsession with youth and vitality. Wyeth also capitalized on a lack of clear study data detailing the long-term risks of HRT—a discovery that was years in the offing.

The “Disease” Of Menopause

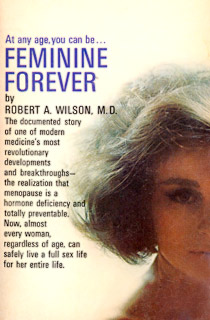

In 1966, gynecologist Robert A. Wilson’s book, Feminine Forever, captured the attention of a generation of aging American women raised during the golden  era of Hollywood films and television. Using words like “flabby,” “shrunken” and “desexed” to describe menopausal women, Wilson’s blatant misogyny seems almost comical today.

era of Hollywood films and television. Using words like “flabby,” “shrunken” and “desexed” to describe menopausal women, Wilson’s blatant misogyny seems almost comical today.

But in its time, Feminine Forever was a bestseller, and it popularized the reclassification of menopause—a natural physiological change—as a “disease.”

“Many physicians,” Wilson wrote, “simply refuse to recognize menopause for what it is — a serious, painful and often crippling disease… No longer need she fret about the cruel irony of women aging faster than men. It is simply no longer true that the sexuality of a woman past forty necessarily declines more rapidly than that of her husband.”

Wilson was essentially promoting estrogen as a feminine “fountain of youth” —one that had already been around for decades. For drug companies, the notion of “healthy” people taking pills every day is nothing short of a holy grail. In Premarin, Wyeth seems to have found it.

Feminine Forever helped convince millions of women and their doctors that the replacement of female sex hormones during menopause was not only helpful, but necessary. Wilson essentially launched HRT into the public consciousness. Sales of HRT products quadrupled in the years following the book’s release.

In 2007, NBC’s chief science and health correspondent, Robert Bazell, wrote: “He defined a natural human condition as a disease and the cure as the ‘off-label’ or unapproved use of a drug that healthy people would take every day for the rest of their lives.”

Bazell’s article goes further, revealing:

“Reporters from The New Republic and the Washington Post discovered documents revealing that Wilson, who died in 1981, received payment for the book and for speaking tours on its behalf from companies making HRT. His son confirmed the payments to the New York Times. The drug companies said too much time had passed to check the records. If they did pay, however, they certainly got their money’s worth.”

Data Wars

Just as the skin creases and cracks as we age, so did the facade of the Premarin empire. By the late 1970s, generic hormones were approved to treat hot flashes, night sweats and vaginal dryness.

The challenge facing Premarin’s maker was to figure out how to continue the drug’s status as the number one HRT.

The challenge facing Premarin’s maker was to figure out how to continue the drug’s status as the number one HRT.

This proved difficult. Two studies in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1975 alerted the public to the elevated risk of estrogen-only therapy and endometrial cancer. Risk appeared to be 4 to 14 times higher for women taking HRT in post-menopause. Suddenly, the shine was off HRT.

But researchers soon found that adding progestin to estrogen therapy (called combined therapy) reduced this risk, and new potential benefits began to emerge.

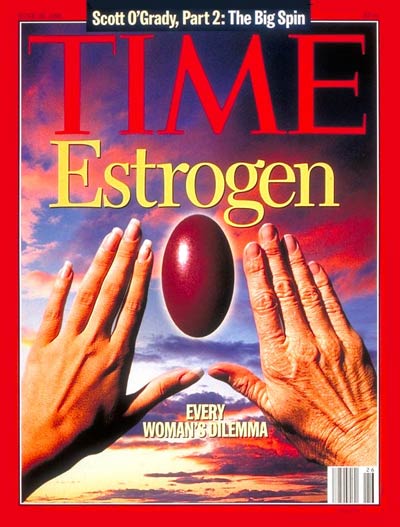

According to ourbodiesourselves.org, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, some observational studies suggested that HRT prevented heart disease. Even though other studies at the time showed a link between HRT and breast cancer and blood clots, marketers took the positive “side benefits” of Prempro (the brand name of combined HRT) and ran.

“During the decades that followed, drug companies promoted and doctors prescribed hormones to women to prevent and treat an increasingly broad range of ailments and experiences associated with aging, from wrinkles and general aches and pains to Alzheimer’s disease, depression, and heart attack,” said Dr. Carol Bates, Director of the Primary Care Program at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, told the New York Times.

“In the 1990s, there was actually tremendous pressure to put women on hormone therapy, and it came from a good  place,” Dr. Bates says. “But it was taken a bit to the extreme.”

place,” Dr. Bates says. “But it was taken a bit to the extreme.”

Paradigm Shift: HERS and WHI

The Heart and Estrogen/Progestin Replacement Study (HERS) was a landmark, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of more than 2000 women with coronary heart disease (CHD) designed to test the efficacy and safety of estrogen plus progestin for prevention of recurrent CHD events.

The two-year study, by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco and published in 2001, challenged the theory that hormone therapy was beneficial for heart disease. It found no preventive benefit of the top-selling hormone formulation, countering years of medical dogma—and pharma marketing.

Not surprisingly, hormone therapy proponents, and Prempro’s maker, loudly dismissed the HERS data. They argued that since the study only enrolled women with preexisting cardiovascular disease, no firm conclusion could be drawn on the cardioprotective effects of HRT in women with healthy hearts.

Fair enough. But several years later, HRT was hit with several knock-out blows from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI), a national study designed to address the most common causes of death, disability, and poor quality of life in postmenopausal women.

WHI was the first randomized clinical trial to assess HRT in healthy women. It included two hormone therapy sub-trials — an estrogen plus progestin study of women with a uterus, and an estrogen-alone study of women who had had hysterectomies.

Both studies showed serious health risks associated with the long-term use of hormones. The estrogen plus progestin arm was halted in July of 2002, three years early, because investigators saw alarming increases in breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, and blood clots in the women who took the hormones.

Both studies showed serious health risks associated with the long-term use of hormones. The estrogen plus progestin arm was halted in July of 2002, three years early, because investigators saw alarming increases in breast cancer, heart disease, stroke, and blood clots in the women who took the hormones.

Though the active treatment cohort also showed less colon cancer and fewer fractures the investigators considered it unethical to continue.

Additional analysis of the WHI data showed that the estrogen-progestin combination did not help with depression, sexual function, vitality, or cognition, and doubled the risk of dementia.

Where Do We Go from Here?

WHI showed women taking hormone therapy were getting sick; thousands of them.

This turn of events forced Wyeth to add a “black box” label to Prempro in 2003 warning that it should not be used to prevent cardiovascular disease. Later that year, the FDA approved a lower dose version to give patients more dosing options.

But by then, many women chose to abandon HRT altogether, or to shun it before even giving it a try.

HERS and WHI trials took the wind out of Prempro’s sails. But the categorical vilification of HRT that followed these studies might be just as overly simplistic as the uncritical adulation of the early Premarin years.

While it is true that HRT was not a fit for women with CHD, elevated cancer risk, or other serious health issues, the truth is, it can be right for some women looking solely for menopause symptom relief — the original indication for Premarin all those decades ago.

How does a woman nearing menopause today sort through decades of conflicting information? And more important, how can her physician help in making the most appropriate decision? (See Timing is Everything in HRT for Menopause).

The solution resides first within her, so to speak, as well as with those she trusts to be part of her health management team. Modern medicine is finally shifting toward a whole-person individualized approach. What works for one woman may be problematic for another, even if those two people share eight out of ten defining characteristics. This is true in most areas of medicine. It is especially true for hormone therapy for menopausal women.

END