People living with chronic digestive disorders like inflammatory bowel disease often figure out the hard way—by trial and error—which food groups trigger their symptom flares.

And since many go for years without competent medical and nutritional guidance, they rely on their own experience, the advice of friends, or online information to create their own elimination diets.

All too often, this means they end up avoiding so many different foods that they become seriously under-nourished.

“Some patients have eliminated so many things that they’re basically living on 4 or 5 foods. Their diets are super restricted. They rely on liquid formulas like Ensure. This becomes problematic because their nutrient intake can be very, very low,” explained Bethany Doerfler, RD, at the 2023 Integrative Healthcare Symposium.

There’s no question that identifying and eliminating trigger foods is essential in the treatment of digestive disorders. But when patients go at it alone, they can end up compromising their overall health in their quest to minimize symptom flares.

Far from being irrational, ARFID begins as a very rational response to a difficult situation. But as the scope of someone’s “safe” foods becomes more and more narrow, this coping strategy brings about its own negative health consequences.

For example, many people who have Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) hear or read about low FODMAP (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) diets, which have been shown to markedly reduce symptoms. Researchers at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, who have done a lot of the work on low FODMAP diets, consider this approach to be a first-line therapy for patients with IBS.

But in the research context, these diets—which eliminate many nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables—are implemented in a careful, controlled way. Further, they are not intended to be followed indefinitely. Patients who are trying to figure it all out on their own may not understand these nuances.

Understanding ARFID

It is important to support proactive patients in their efforts to avoid foods that provoke painful, socially awkward, and sometimes truly debilitating symptoms. But it is equally important to recognize when someone’s diligence is leading to malnutrition.

Food restriction motivated by a desire to mitigate symptoms can become its own form of pathology says Doerfler, of the Functional Bowel and Neurogastromotility Team at Northwestern University Medical Center, Chicago.

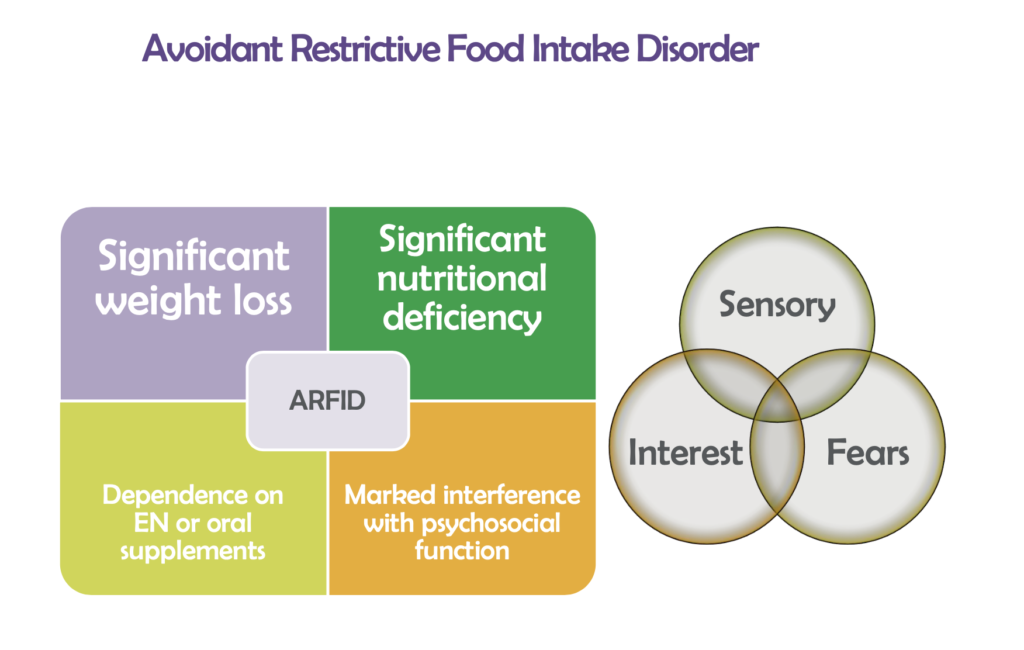

Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (RFID) is a relatively new diagnosis, introduced into the DSM-5 in 2013, but it’s an important one for physicians to keep in mind. ARFID is defined as a severe limitation on the number, types, and quantity of foods consumed, leading to significant weight loss, nutritional deficiency, dependence on enteral formulas and/or supplements, and marked interference with psychosocial function.

It’s a common problem among people with GI conditions, Doerfler says.

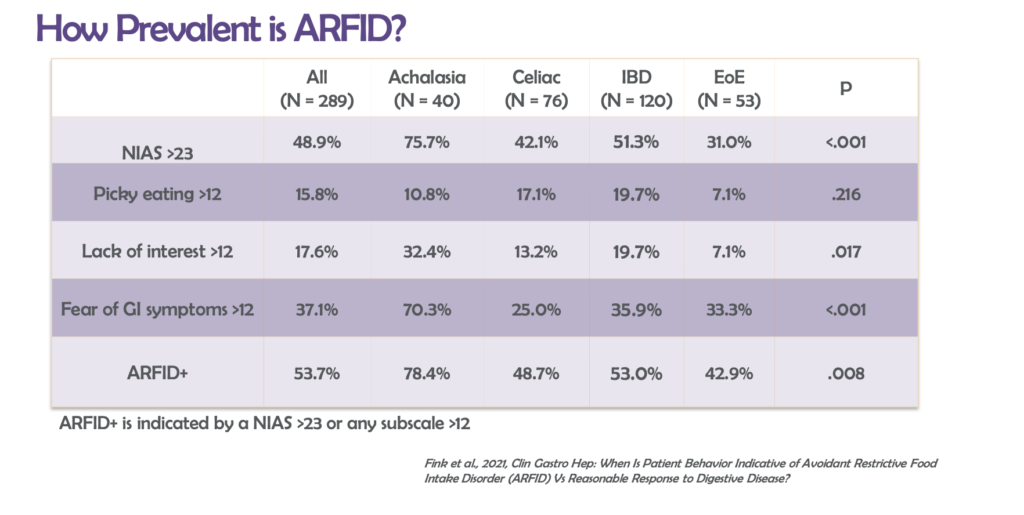

According to a 2022 study by Margaret Fink and colleagues at Northwestern, 54% of a cohort of 289 patients with chronic digestive disorders met the criteria for ARFID, based on their responses to a 9-item standardized ARFID screening tool.

The group included patients with Achalasia, Celiac, IBD, Eosinophilic Esophagitis. ARFID prevalence was highest among those with achalasia (78%) and IBD (53%). The lowest rate was among those with EoE, though 43% of these patients fit the ARFID definition.

Doerfler told IHS attendees that nearly 70% of all people with older-onset IBD significantly restrict their diets in order to minimize symptoms.

A Reasonable Motivation

ARFID shares many clinical features with anorexia and bulimia, but the motivations underlying ARFID are quite distinct, and it’s important not to confuse these conditions, Doerfler says.

Anorexia and bulimia are driven by a pathological desire to lose weight, usually in a context of extreme distress about body image and, often, an inability to accurately perceive one’s own actual morphology.

ARFID arises from a desire to avoid symptoms such as constant diarrhea, flatulence, or abdominal pain.

“It develops because patients don’t want to constantly experience burdensome and disruptive symptoms. They want to socialize, go on dates, go to work, participate in family events, without constantly worrying about where they’ll be able to find a bathroom or whether they’ll feel well enough to enjoy themselves,” Doerfler explained.

In a sense, ARFID is the result of a healthy impulse that’s gone too far.

“Some patients have eliminated so many things that they’re basically living on 4 or 5 foods. Their diets are super restricted. They rely on liquid formulas like Ensure. This becomes problematic because their nutrient intake can be very, very low.”

–Bethany Doerfler, RD, Northwestern University Medical Center

It’s important to recognize the intense emotional and social stress that chronic GI disorders can cause. Instead of occasions for joy and pleasure, mealtimes often become unpleasant exercises in risk-benefit analysis.

Quoting one of the patients in their research cohort, Hana Zickgraf and colleagues titled their 2022 paper on the Fear of Food Questionnaire: “If I could survive without eating, it would be a huge relief.”

Usually, patients with ARFID are aware that they’re losing too much weight or that they’re undernourished. “These people know they are in a bad way, but they don’t know how to expand beyond their very small number of “safe” foods.”

Guidance is Essential

This is where good nutritional guidance can be so helpful. Knowing which foods can be safely substituted for the problematic ones can transform these patients’ lives. Further, many patients will find that they can tolerate some of their ‘trigger’ foods occasionally and in small amounts.

In other words, restrictive diets need to be carefully tailored and individualized. Broad elimination of entire food categories is what gets many patients into trouble.

The first step, of course, is to recognize when a patient has ARFID. Doerfler says the most obvious red flags are major weight loss, and signs of poor overall nutritional status.

Always ask patients about their eating patterns.

“If someone says, ‘I eat the same thing every day, and whenever I try something else, I get really bad diarrhea,’ or some other GI problem, that’s a sign that this patient is dealing with ARFID.”

But don’t stop with the basic question. Dig a little deeper. Doerfler advises asking:

- What is your perception of your own diet?

- How much is your diet guided by your GI symptoms?

- Do you find it difficult to eat enough? Do you only eat small portions because you’re worried about symtoms?

- Are mealtimes stressful? Do you have to push yourself to eat?

- What happens if you eat different foods outside your usual “safe” foods?

- How has the way you eat affected you socially?

- Are family members or friends concerned about your dietary restrictions and your health?

Then, describe ARFID and ask, “Does this sound like you?” Many people will nod their heads affirmatively.

“If someone says, ‘I eat the same thing every day, and whenever I try something else, I get really bad diarrhea,’ or some other GI problem, that’s a sign that this patient is dealing with ARFID.”

Clinical management of ARFID usually requires a combination of nutritionally-focused counseling focused on helping patients to expand their dietary repertoires and improve their nutritional status, and psychological counseling (cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy) to learn new behavior patterns, unlearn old ones, and manage the fears and anxieties.

“Helping someone with ARFID move toward a more inclusive, healthier diet requires teamwork and commitment,” says Doerfler.

One of the central goals is to identify which foods are most problematic and therefore most necessary to avoid, and which ones the patient can actually tolerate.

For example, many patients with IBD who follow the low-FODMAP diet find that they are OK when they eat:

• 1/4-1/2 Avocado

• 3/4 cup pickled Beets

• 1/2 cob corn

• 4 Brussels Sprouts

• 1/2 cup Squash

• 12-20 almonds

All of those foods technically contain FODMAPS and would be eliminated on a strict low-FODMAP diet. But patients can usually tolerate small amounts without problems. FODMAP-friendly grains include: gluten-free sprouted wheat, oats, quinoa, and sourdough cornmeal. So most patients won’t need to completely eliminate all grains.

Doerfler added that seeds—sunflower, chia, and pumpkin—are valuable allies in helping patients increase the nutrient density of their meals. They’re rich in magnesium, fiber, vitamin E, selenium, and B vitamins. Plus, they contain a lot of protein and healthy fats. Seeds are versatile, and easy to add to salads, soups, or stews. And they make for good healthy snacks.

Some patients with extreme ARFID may benefit from intensive inpatient or outpatient eating disorder treatment programs. But again, it is important to recognize that this condition is different from anorexia and bulimia—the most common conditions treated in these settings.

To help practitioners get a better grip on the care of patients with complex digestive problems, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recently partnered with Dietitians in Gluten and Gastrointestinal Disorders (DIGID) to foster interdisciplinary collaboration, aggregate evidence for nutritional interventions, and provide the wider community with effective ways of finding practitioners who have expertise in working with these patients.

Challenging Bias

There are a lot of social stigmas around eating disorders, and these negative biases add to the complexity of an already difficult situation.

Dr. Doerfler urged practitioners to examine their own attitudes toward people with eating disorders.

“Don’t stigmatize or pathologize eating disorders in general, and don’t treat ARFID as some sort of irrational ‘psychological’ problem,” she said.

Far from being irrational, ARFID begins as a very rational response to a difficult situation. But as the scope of someone’s “safe” foods becomes more and more narrow, this coping strategy brings about its own negative health consequences.

By recognizing when someone’s showing signs of ARFID, and then helping them expand their diets while still minimizing the most problematic trigger foods, you will go a long way in improving the overall health and wellbeing of patients dealing with chronic digestive disorders.

END