What do apples, onions, hummus, and ice cream have in common? They’re all rich in FODMAPs: a set of short-chain carbohydrates that can set off the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), such as bloating, gas, cramping, constipation and/or diarrhea.

Short-term adherence to FODMAP-free diets can be very effective in reducing the symptom burden associated with IBS. But over time, these diets themselves can become problematic because they eliminate some of the most nutritious, flavorful, and fiber-rich foods. That’s not good for our patients….or their microbiomes!

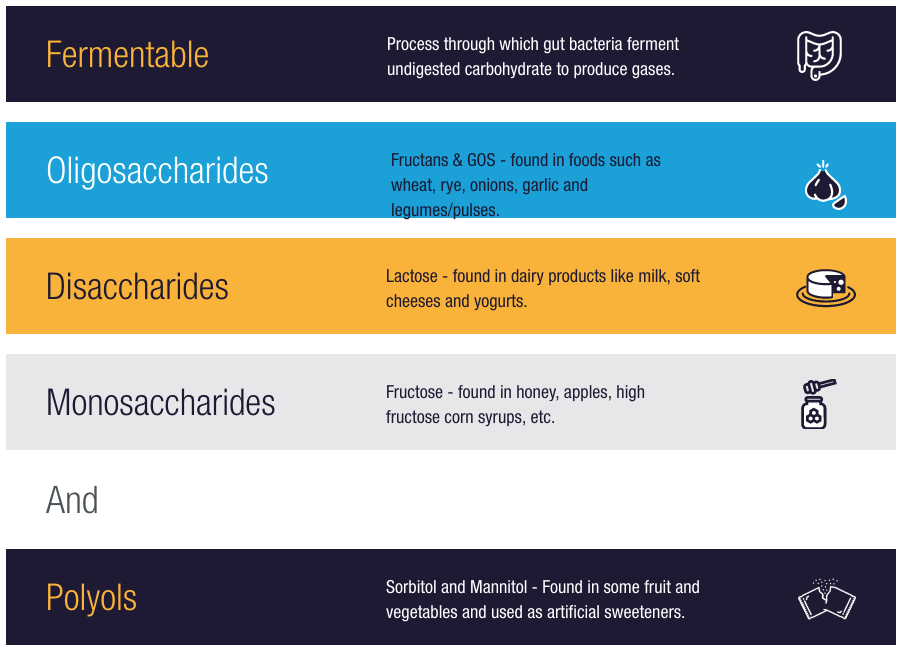

FODMAPs is an acronym that stands for “Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols.” They are a set of fermentable sugars and prebiotic fibers present in a wide range of carbohydrate-dense foods.

- Oligosaccharides include galacto-oligosaccharides and fructans, present in the gluten containing grains (wheat, barley, and rye), as well as onions, garlic, legumes, and some types of nuts.

- Disaccharides include sucrose, and lactose found in cow’s milk, soft cheeses, and yogurt.

- Monosaccharides include fructose, glucose, and galactose, present in apples, pears, honey, and obviously in high-fructose corn syrup.

- Polyols are the alcohol-based sugars, such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, erythritol; Polyols are also present in some fruits and vegetables, as well as the synthetic sweetener, sucralose.

The gut microbiota ferments these sugars and fibers into gasses such as hydrogen and methane, and also to short chain fatty acids, such as butyric acid, which is the primary fuel for the epithelial lining of the intestinal tract.

In individuals with IBS, excessive intake of these fermentable carbohydrates can increase small intestinal water volume and gas production, stretching the nerves lining the intestinal wall, leading to the visceral hypersensitivity, cramping pain, and watery stools associated with IBS. Nutrient malabsorption and intestinal hyperpermeability often follow.

Roughly 75% of patients with IBS will have a positive response in terms of GI symptom reduction, while following a low-FODMAP diet. And it happens quickly, often within 48 hours of FODMAP elimination.

FODMAP-rich foods can aggravate indigestion and promote bacterial overgrowth. This is especially true if colonic bacteria have migrated through the ileocecal value to proliferate in the small intestine—the classic Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) scenario.

For many patients with IBS and SIBO, a low FODMAP diet makes good sense, and there’s research to support that approach.

Marked Symptom Relief

Dietitian Sue Shepherd, gastroenterologist Peter Gibson, and their colleagues at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, are world-renowned for developing and testing a low-FODMAP regimen which they believe to be a first-line therapy for patients with IBS.

In an elegant, well-designed, controlled, crossover study of 30 patients with IBS, the Monash group compared the effects of their low-FODMAP diet versus a standard Australian diet.

For both arms of the study, the researchers provided subjects with three main meals and three snacks per day, along with detailed meal plan instructions. The meal packages provided an average of 8 MJ/day of total energy, and met the recommended daily servings of all food groups.

The low FODMAP diet kept oligosaccharide, fructose in excess of glucose, and polyol content down below 0.5 g each per sitting. In both diets, the meal plans kept lactose to less than 5 grams per sitting. The authors explained that, “Because lactose is present in much higher concentrations in the diet than all other FODMAPs, the presence of lactase deficiency and subsequent malabsorption of large loads of lactose may mask the influence of the other FODMAPs.”

The low-FODMAP diet also included a daily average of 3g of psyllium and 5g of Hi-Maize 220—an amylose-rich resistant starch—each day to make up for fiber and resistance starch lost through elimination of FODMAP-rich produce.

Patients were randomly assigned to one or the other diet for 21 days, followed by a 21-day washout period during which they could resume their usual eating habits. They were then assigned to the opposite meal plan for another 21 days.

The results were striking. The low-FODMAP diet effectively reduced functional GI symptoms across a range of parameters.

“Subjects with IBS had lower overall gastrointestinal symptom scores (22.8; 95% confidence interval, 16.7-28.8 mm) while on a diet low in FODMAPs, compared with the Australian diet (44.9; 95% confidence interval, 36.6-53.1 mm; P < .001) and the subjects’ habitual diet. Bloating, pain, and passage of wind also were reduced while IBS patients were on the low-FODMAP diet.” (Halmos E, et al. Gastroenterology. 2014)

Since FODMAP-containing foods are also among the most phytonutrient-rich and nutritious foods, it is unwise—if not impossible– to eliminate all of them forever. One loses a lot of fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients along with the FODMAPs.

The low-FODMAP diet in this study was not entirely gluten-free, and the trial was not designed to specifically look at the effects of gluten. But because FODMAP-rich wheat, rye, and barley are cut from this diet, patients will inevitably reduce their gluten intake while following it. That’s an added benefit for people who are gluten-sensitive.

Tools to Support Adherence

In a review article published in the journal, Gut, in 2017, researchers Heidi Staudacher and Kevin Whelan of King’s College London, point out that, “There are currently at least 10 randomized controlled trials or randomized comparative trials showing the low FODMAP diet leads to clinical response in 50%–80% of patients with IBS, in particular with improvements in bloating, flatulence, diarrhea and global symptoms.”

The most widely used low-FODMAP diet is a 3-phase approach consisting of a 2–6-week elimination phase to observe for symptom improvement, followed by a 6–8-week reintroduction phase to identify triggering foods. Then, there’s a long-term “personalization phase” during which the goal is to maintain symptom improvement with the fewest necessary dietary restrictions.

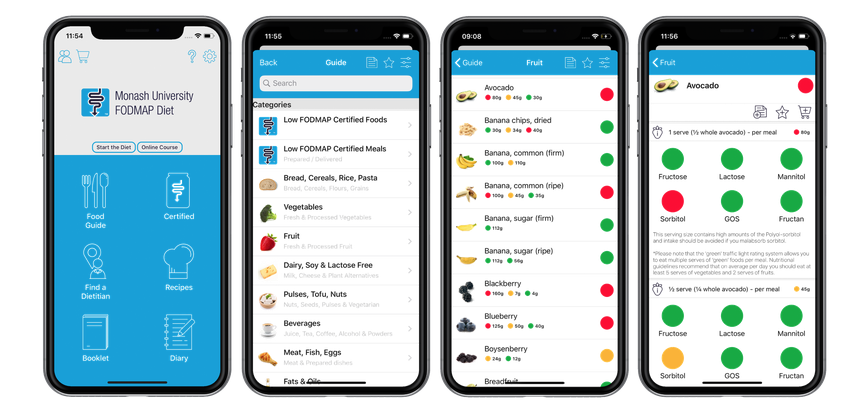

To support patient compliance, the Monash University team offers multiple educational materials for both patients and clinicians. They developed a smartphone app that rates the fermentability of hundreds of foods using a “fermentability scale” based on lab testing and clinical tolerability of IBS patients.

The Monash app rates each food with a qualitative “traffic light” color system: green foods have low levels of the problematic oligosaccharides, fructose, polyols, and lactose; red light foods are high in one or more of them. The system also offers a quantitative assessment of two different portion sizes, guiding the user to determine the levels of a particular food they might find tolerable.

Given the prevalence of IBS—it is the most commonly diagnosed functional GI disorder, affecting between 10% and 20% of the world’s population–we need to gain experience working with low-FODMAP diets. They don’t work for everyone but they can help many people and they’re now being considered a first line therapy.

But it’s complicated. There are several versions of the low-FODMAP diet and they vary somewhat in terms of their “culprit” lists. All of the regimens can be challenging, adherence-wise, and require the interest and commitment of the patient.

Cookbooks can provide invaluable support for adherence. The Complete Low FODMAP Cookbook by Monash University’s Dr. Sue Sheperd offers 150 simple, flavorful, and gut friendly recipes to ease the symptoms of IBS and other digestive disorders. The Monash University website also features dozens of low FODMAP recipes at https://www.monashfodmap.com/recipe/

Another take on a low FODMAP diet is provided by Norm Robillard in, The Fast Tract Diet – IBS. Dr. Alison Siebecker’s site, SIBO Info, offers a multitude of resources for the low FODMAP diet in the treatment of SIBO.

A Short-Term Strategy

Roughly 75% of patients with IBS will have a positive response in terms of GI symptom reduction, while following a low-FODMAP diet. And it happens quickly, often within 48 hours of FODMAP elimination.

But like all elimination diets, this can be the nutritional equivalent of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Since FODMAP-containing foods are also among the most phytonutrient-rich and nutritious foods, it is unwise—if not impossible– to eliminate all of them forever. One loses a lot of fiber, vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients along with the FODMAPs.

This can also be detrimental to the microbiome.

Long-term FODMAP elimination is accompanied by changes in the gut microbiota and its metabolic output. Low FODMAP intake reduces diversity of the gut microbiome and decreases production of SCFAs. Bifidobacteria populations decline, as do butyrate-producing organisms.

Halmos and colleagues at Monash studied 27 patients with IBS using two diets with different FODMAP content. They then crossed the subjects over to the other diet after a 21-day washout period.

They found that dietary FODMAP content had direct and far-reaching impact on microbiome composition and structure.

The low FODMAP diet was associated with lower absolute abundance of total bacteria, butyrate-producing bacteria, prebiotic bacteria, and Akkermansia muciniphila and Ruminococcus gnavus. “Marked lower relative abundances of Clostridium cluster XIVa and A. muciniphila, and a significantly higher abundance of R. torques were also observed.”

The authors note that “the low FODMAP intake was associated with reduced absolute abundance of bacteria, but the higher FODMAP intake associated with the typical Australian diet showed evidence of specific stimulation of the growth of bacterial groups with putative health benefits.” (Halmos EP, et al. Gut. 2015)

They strongly advise against low-FODMAP diets for asymptomatic people, and emphasize that symptomatic individuals should only follow these diets for periods of weeks, not indefinitely. They advocate for liberalization of FODMAP restriction, “to the level of adequate symptom control.”

The low FODMAP diet was associated with lower absolute abundance of total bacteria, butyrate-producing bacteria, prebiotic bacteria, and Akkermansia muciniphila and Ruminococcus gnavus.

The King’s College group also investigated the effect of a 4-week low FODMAP diet on stool microbiota in IBS patients. Using fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques, they found that a 50% reduction in FODMAP intake led to “a marked 6-fold reduction in relative abundance of Bifidobacteria compared with controls who maintained their habitual diet.” (Staudacher HM, Whelan K. Gut. 2017).

Individualization is Key

So, summing it up, on one hand there’s substantial evidence that low FODMAP diets are effective in reducing symptoms of IBS, but on the other hand, there’s also evidence that the diet itself can be problematic, leading to microbiome dysregulation, dysbiosis, and even potentially increased risk of colon cancer.

Our challenge is to discover which of the myriad FODMAP-containing foods might be triggering the symptoms of each individual patient. Given the variability of our genomes, gut microbiome, and the environments in which we live, there is a lot of variance in reactivity to foods.

We need additional research to fully understand the impact of FODMAPs—and their elimination–on the microbiome. Future research will focus on identifying the effect of specific FODMAPs on the abundance of various microbial populations, their metabolic outputs, and the long-term consequences of this diet in IBS and other gastrointestinal conditions.

Our challenge is to discover which of the myriad FODMAP-containing foods might be triggering the symptoms of each individual patient. Given the variability of our genomes, gut microbiome, and the environments in which we live, there is a lot of variance in reactivity to foods.

Tools like the Monash app put power in our patients’ hands to experiment and identify the unique contributors to their symptoms. With time and careful tracking, people with IBS often find they can tolerate certain FODMAPs but not others. Part of our job as clinicians is to help them figure this out.

A low FODMAP diet is intended to be progressive, beginning with elimination and followed by reintroduction and determination of tolerable quantities of fermentable carbohydrates. Reintroduction of as many of these foods as possible is important for diversity of a healthy microbial flora and for SCFA production.

The reintroduction process of individual FODMAP foods should begin 2-6 weeks after intensive elimination. Even the trailblazers of the low-FODMAP diet recognize that this should not be a “forever” diet.

Some patients who experience symptom flares from FODMAPs may experience some relief by taking enzyme formulas such as Beano, that contain alpha-galactosidase, prior to eating known trigger foods. Note that people with IBS may need more than the labelled dose of these products to obtain relief.

END