Women who drink diet soda or consume other aspartame-containing products during pregnancy may be unwittingly putting their male children at risk for autism spectrum disorders.

That’s the troubling signal from a new study of more than 350 maternal-child pairs, by Sharon Fowler, PhD, and colleagues at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center, San Antonio.

The study, published in the journal Nutrients in September, showed a strong association between autism and related neurological disorders in young boys, and daily consumption of aspartame by their mothers during pregnancy and nursing.

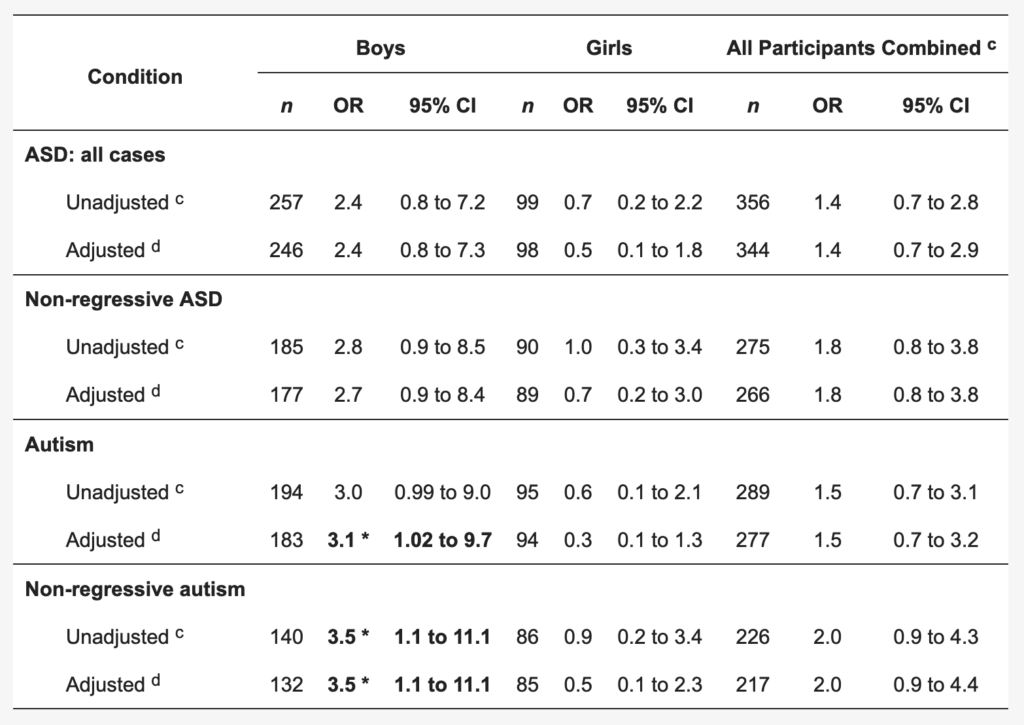

Dr. Fowler and her team gathered retrospective dietary data on intake of diet soda and other forms of aspartame from biological mothers of 356 young children. Within that cohort, there were 235 kids who had been diagnosed with autism or autism spectrum disorders, and 121 who were deemed “neurotypical” for their age.

The mothers filled out retrospective questionnaires about their intake of diet sodas and other diet drinks during pregnancy and breastfeeding.

The question was framed as follows: “While you were pregnant or breastfeeding your child, how often did you drink diet drinks containing artificial sweeteners? Please count diet sodas first, such as Diet Coke, Diet Dr. Pepper, and Diet Sprite, and then other diet drinks, such as Crystal Light, sugar-free Kool-Aid, Slim-Fast, and other ‘lite’ drinks?”.

From the responses, Fowler and colleagues were able to calculate mean daily, weekly, and monthly intake of artificially-sweetened diet drinks.

The questionnaire also asked: “While you were pregnant or breastfeeding your child, how many little packets of low-calorie sweeteners (such as Sweet ‘N Low, Equal or Splenda) did you use in your coffee, tea, or other foods and beverages? In answering the question, please keep in mind the number of drinks you had each day, and how many packets of sweetener you added to each drink. Also, please include the number of packets you used in cereal or other food”.

This question enabled the UT researchers to estimate frequency and intensity of aspartame exposure, independent of soft drinks.

How Sweet It Isn’t

“We hypothesized that gestational/early-life exposure to one or more diet sodas per day or equivalent aspartame (≥177 mg/day) increases autism risk,” the authors note.

Dr. Fowler says the roots of that hypothesis began with case reports.

“Over a decade ago, people began contacting us to share their stories of neurological problems they had developed after using diet sodas daily for some time. These were dramatic stories. They included a young woman who became depressed and suicidal; a middle-aged man who did not have diabetes, but developed debilitating and unexplainable pains in his legs; and a young pregnant woman who developed headaches and swelling and pain in her legs every day.

In all three cases, their severe symptoms disappeared once they quit using diet sodas, and reappeared when they tried using them again,” she said in a video interview following publication of the report.

She added that in the medical literature, prevalence of autism in the US began to accelerate in the early 1980s, “around the same time that aspartame was introduced in the US diet. We became concerned: could there be a connection?”

The UT study, though not conclusive, and definitely not the basis for proving causality, showed some disturbing correlations.

Among the 121 neurotypical boys, only 7.4% had had daily gestational and early life exposure to diet sodas via their mothers’ intake. But among those with any form of autism spectrum disorder, 16.3% had daily exposures during gestation and/or breastfeeding. And among the 86 boys with non-regressive early-onset autism, the number was 22.1%. That, Dr. Fowler points out, is three times the rate among controls.

They found a very similar pattern for aspartame consumption. Nearly one in four boys (23.3%) with non-regressive autism had daily exposure to 177 mg or more of aspartame in early life via their mothers’ use of sweeteners. For all autism cases, that figure was 21%. In contrast, only 7% of the non-autistic/ASD control group had high aspartame exposure levels in early life.

Translating the soda data into odds ratios, Dr. Fowler and colleagues claim that boys with autism were 3 times as likely to have been exposed to diet sodas daily in early life, compared with controls. Among the non-regressive early onset autism cases, the adjusted odds ratio was 3.5 times greater.

The apparent connection between diet soda, aspartame, and autism seems to be gender-linked. There were 32 cases of autism/ASD among the 99 female children in the cohort, but the authors did not find any statistical correlation with maternal diet soda or aspartame consumption among the girls.

“Our results do not prove causality,” Fowler stressed. “More research and a larger prospective cohort study are needed to gather additional data on exposures, maternal risk factors, and diagnoses. But taken together with results from earlier studies, our findings raise a red flag of warning.”

Multiple Mechanisms

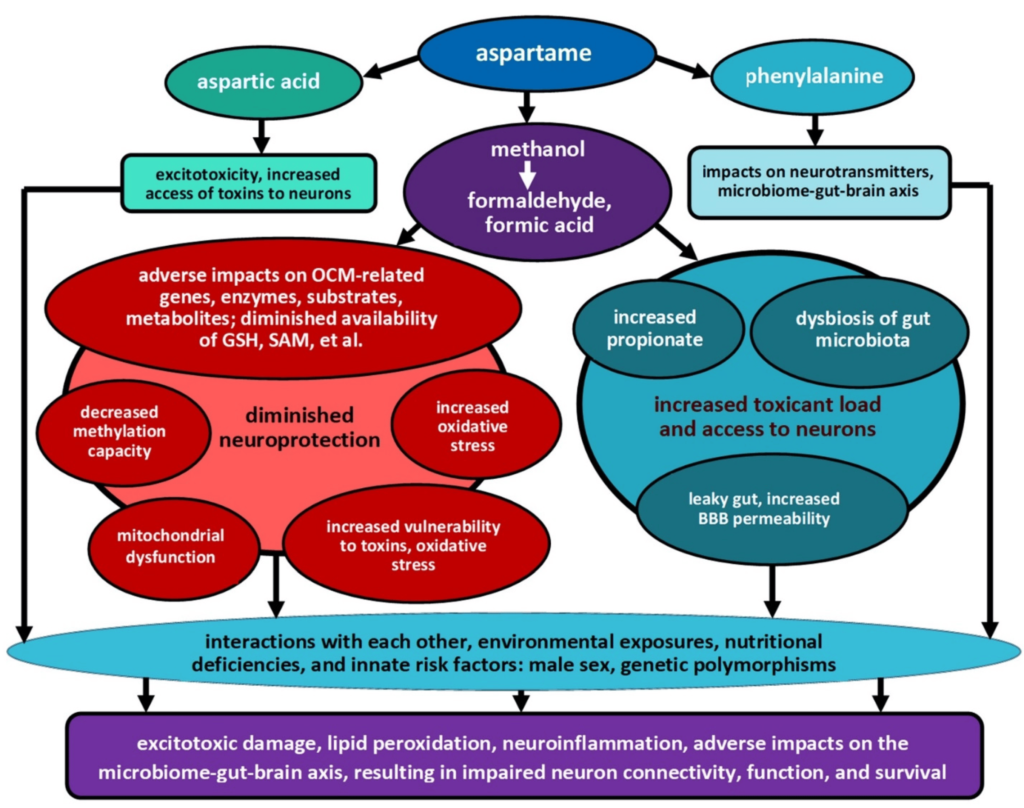

According to the UT reseachers, there are several biological mechanisms through which maternal intake of aspartame during pregnancy could potentially raise the risk of neurological damage in their children.

The three main first-phase metabolites of aspartame are: aspartic acid, phenylalanine, and methanol. There’s research, to suggest that all three can impact neurological function.

Aspartic acid is, itself, an excitatory neurotransmitter, while phenylalanine plays a role in regulation of neurotransmitters. Methanol is further metabolized into formaldehyde, formate, and several other compounds all of which can be neurotoxic (Humphries P, et al. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008). Fowler and colleagues point out that primates, including humans, are particularly vulnerable to the adverse impacts of methanol (Monte WC. Med Hypotheses. 2010; Iyyaswami A, Rathinasamy S. J Biosci. 2012).

Exposure to methanol in combination with formaldehyde, which rise in the blood following aspartame intake, promotes neuronal apoptosis and alters neurotransmitter levels, potentially leading to neurodegeneration and cognitive impairment.

Fowler added that aspartic acid is not only excitotoxic; it increases the susceptibility of neurons to other toxins. Formaldehyde and formic acid—the downstream metabolites of methanol, impair methylation capacity and mitochondrial function, while increasing oxidative stress.

The adverse impact of aspartame metabolites is not limited to the central nervous system: methanol and its metabolites can increase the permeability of the intestinal wall as well as the blood brain barrier. And phenylalanine can be disruptive to the gut microbiome, which in turn, affects the gut-brain axis.

“Together these impacts could contribute to a perfect storm for children already genetically at higher risk of developing autism, by diminishing neuroprotection while simultaneously increasing the toxin load in developing neurons,” Dr. Fowler says.

Troubled History

This new study emerged several months after the World Health Organization’s International Agency for Cancer Research deemed aspartame “possibly carcinogenic to humans.” The Food and Drug Administration in the US dismissed that position, stating that the conclusion is based on very limited evidence, and that the majority of scientific evidence—and nearly 50 years of real-world market experience—weigh in favor of aspartame’s safety.

The FDA, which regulates aspartame as a food additive, has set the acceptable daily intake (the amount that can be ingested daily over a lifetime without appreciable health risk) of aspartame at 50 mg/kg per day, roughly equivalent to 50 packets of aspartame-containing sweeteners per day.

Known on the US consumer market as NutraSweet or Equal, aspartame is considered a “high-intensity” sweetener. This means that according to the arcane science of sweetness test panels, it registers to our senses as roughly 180 to 200 times sweeter than sucrose.

Aspartame was discovered in 1965, by a chemist named James Schlatter at GD Searle & Company, and was initially on track for use in research on anti-ulcer drugs. Schlatter discovered its unique sweetness by accident, after licking his finger which had been in contact with the substance. With the help of Norwegian chemist Torunn Atteraas Garin, famed for her work in decaffeinating coffee, the molecule was quickly re-routed to market as an artificial low-calorie sugar substitute.

It entered the US market in 1974, and has been the subject of controversy ever since. Roughly one year later, an FDA task took issue with the quality of 25 studies funded by Searle, including 15 studies on aspartame, which the agency deemed necessary to authenticate. Though the reviewers did find minor methodological flaws in Searle’s chain of evidence, they were not big enough to warrant regulatory action.

In 1980, prompted by animal suggesting a possible link between aspartame and brain cancer, the FDA summoned a Public Board of Inquiry to review the evidence. That board concluded that the evidence was insufficient to conclude that the sweetener was carcinogenic in animals, let alone in humans.

In the introduction to their study, Fowler and colleagues note that since the early 1980s, the FDA has logged numerous reports of adverse reactions to aspartame, including headache, anxiety, depression, mood disorders, cognitive problems and seizures. But there have never been any conclusive studies proving causality, and the FDA has never deemed any of these reports sufficient to declare aspartame unsafe.

Rising Consumption

Safety questions aside, Americans young and old consume a lot of artificial low calorie sweeteners.

According to a 2017 analysis of data on roughly 17,000 men, women, and children by researchers at George Washington University, 41% of all adults and 25% of children regularly use foods and beverages containing aspartame, sucralose, or saccharin. Compared with 1999, these numbers represent a 54% increase among adults, and a startling 200% increase among people under the age of 18 (Sylvetski AC, et al. J Acad Nutr Dietetics. 2017).

Among the regular consumers of low-calorie sweeteners, 44% of the adults and 20% of the children say their intake was more than once per day. Nearly one in five of the adults (17%) said they ate or drank products containing low-calorie sweeteners thrice daily or more.

And this is a worldwide phenomenon. According to Statista, a global market research company, worldwide revenue from products containing artificial sweeteners is predicted to grow by 40% in the next five years, reaching approximately $33.8 billion by 2028.

Dr. Fowler and colleagues point out in their study that aspartame is one of the world’s most common artificial sweeteners, one that has been used in more than 6,000 food, beverage, and pharmaceutical products over the past 40 years. “Diet” sodas are a leading mode of aspartame delivery.

She emphasized that her group’s finding of a potential link between maternal sweetener consumption and childhood autism are cause for concern and ground for further research. The UT study has all the limitations and biases inherent in any study based on retrospective dietary questionnaires. Further, there were no available data on maternal health status, obesity, diabetes, or neurocognitive disorders—all factors which could affect risk of autism in children.

All that said, their discoveries merit serious consideration especially because there are multiple biochemical pathways by which aspartame could potentially be neurotoxic to vulnerable kids.

“Although daily early-life exposure to diet soda/aspartame represents only one potential risk-increasing exposure within the total exposome of the developing child, nonetheless—within the context of male sex and other risk factors—it might contribute to overwhelming the delicate neurodevelopmental susceptibility tipping point of a child already at increased risk,” the authors note.

“We hope women will consider carefully the potential for harm to their unborn children when deciding whether to use these products during pregnancy and breast-feeding,” Dr. Fowler said in an interview.

More surprising than the findings themselves was the fact that outside of a September 24 report by Fox News, and some local coverage in Texas regional media, mainstream media outlets have largely ignored this important flag-raising study.

END