It’s a common clinical scenario: A middle-aged patient comes in, saying something like, “I used to be so thin and now I’m not. I exercise as much as I did when I was younger, and I eat the same. But I keep gaining weight. I just can’t keep it off. It must be my metabolism.”

Many people, practitioners and patients alike, believe that sometime during the 5th decade of life, there’s an inevitable metabolic slowdown that causes people to gain weight despite a generally healthy lifestyle.

It’s a handy explanation. The only problem is, it is not true.

“Metabolic rate, on average, really does not change much from age 20 to age 60,” said

Heidi Skolnik, MS, CDM, a nutrition specialist at the Women’s Sports Medicine Center, at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City.

Speaking at the 2023 Integrative Healthcare Symposium, Skolnik shed light on several erroneous notions about human metabolism. The biggest one is that midlife weight gain is due to a sudden metabolic decline.

“The tissues are able to metabolize at more or less the same level at age 60 as at age 20. It’s just that by age 60, you’ve usually lost a lot of your most metabolically-active tissue, the skeletal muscle.”

–Heidi Skolnik, MS, CDN

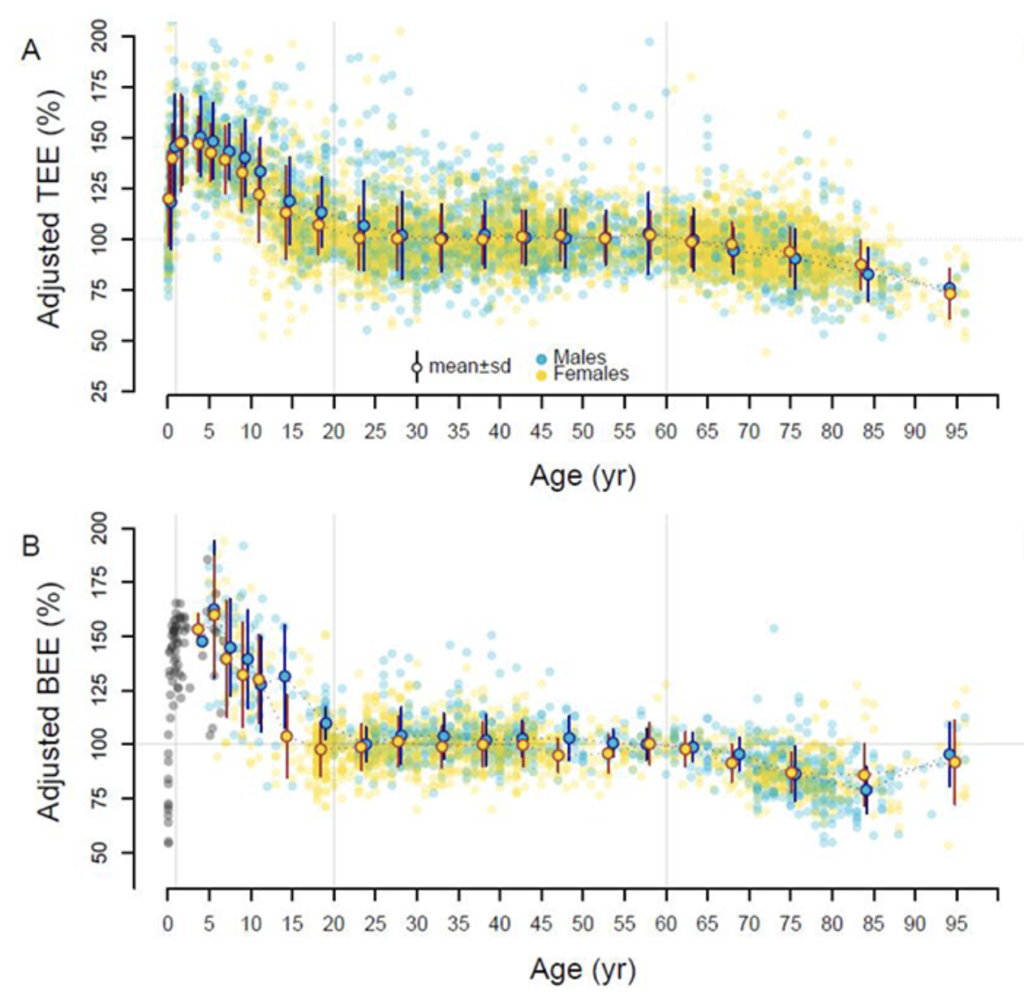

In a landmark 2021 paper, Herman Ponzer of the Duke University Global Health Institute and a team of researchers from all over the globe showed that basal energy expenditure is actually quite stable from the 3rd through the 6th decades of life. This is true for males as well as females, and even during pregnancy, womens’ basal metabolic rates tend to be pretty consistent.

The findings are based on detailed analysis of data from more than 6,400 people (64% female) from 29 countries, and representing a wide range of racial and ethnic subgroups.

It’s only after age 70 that there’s a significant physiological decline in basal metabolism.

Missing Muscle

So, why do so many people who were lean going into their 40s find themselves gaining a lot of weight as they hit their 50s?

Leaving aside the fact that most middle-aged people do not eat or exercise the same way they did in their 20s and 30s (though they think they do), there is an important physiological change that occurs in midlife, one that partially accounts for the added girth: loss of lean muscle mass.

Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY

“The tissues are able to metabolize at more or less the same level at age 60 as at age 20. It’s just that by age 60, you’ve usually lost a lot of your most metabolically-active tissue, the skeletal muscle,” Skolnik explained.

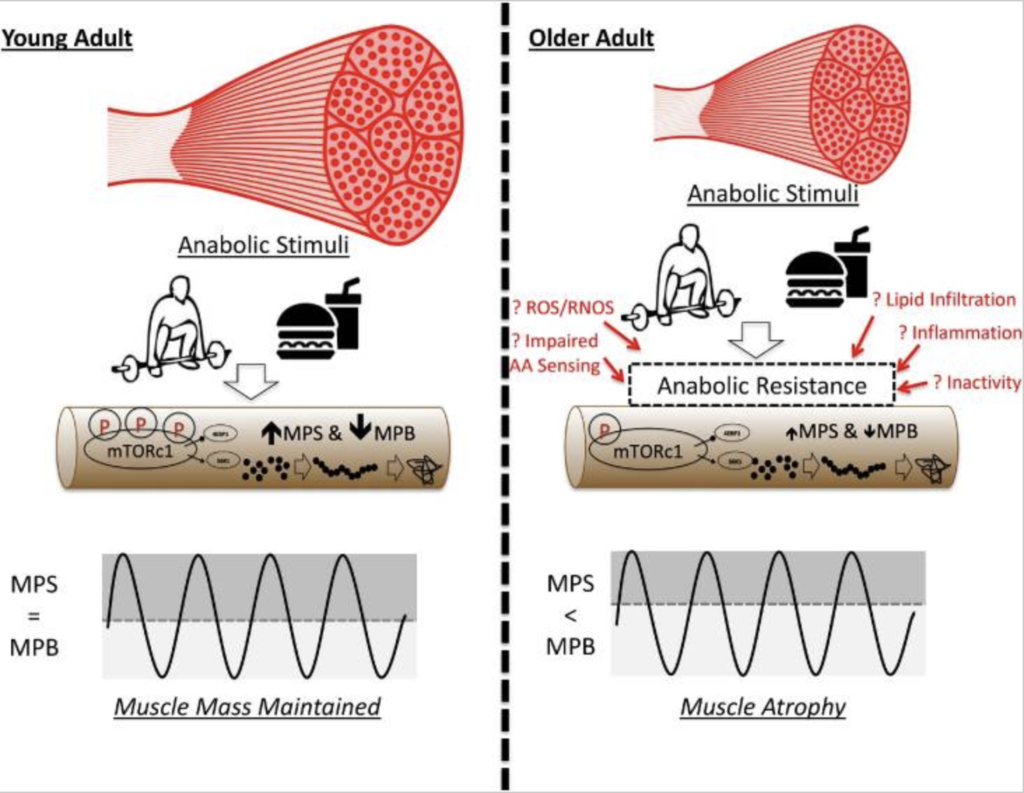

Typically, people lose somewhere around 1% of their total muscle mass per year starting in middle age. By the 8th or 9th decade of life, they’ve lost as much as 50% of their peak muscle mass. This change reflects an imbalance between muscle protein synthesis and muscle tissue breakdown, with the balance tipping toward the latter (Wilkinson DJ, et al. Ageing Res Rev. 2018).

This means that over time lean muscle mass relative to total body weight tends to decline, predisposing people to further adiposity.

Anabolic Resistance

Inactivity plays a big role in this change, as does inflammation. Chronic inflammatory conditions, coupled with increases in cortisol and other catabolic hormones, contribute to midlife muscle atrophy.

There’s also a phenomenon called anabolic resistance.

All other factors being equal, it is more difficult for older people to push the physiological muscle-building ‘button’ than it is for younger people. It may seem paradoxical, but older people need more protein than younger people to build the same amount of muscle.

For example, Wilkinson and colleagues at the University of Nottingham, UK, showed that young men only need 0.24 grams of protein per kilogram of body mass to build muscle, while older men need 0.40 grams per kilogram (Wilkinson DJ, et al. Ageing Res Rev. 2018). The same daily protein intake that was enough to maintain muscle mass when someone was 30, will likely be inadequate by the time that person is 50.

Skolnik stressed that anabolic resistance is a predictable involuntary biological phenomenon. It’s not a reflection of “lack of willpower” or bad dietary choices, though obviously lifestyle factors play a role.

Left unchecked, loss of lean muscle mass has a lot of negative consequences. Sarcopenia, which affects up to 13% of all people between the ages of 60 and 70, and well over 50% of people in the 80-plus bracket, is an independent predictor of falls, morbidity, and mortality.

Further, many of the so-called “diseases of aging” are, in some way, related to muscle loss. Muscle function affects bone metabolism, so consequently it influences risk of osteoporosis. Greater muscle mass is correlated with lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. And because muscle mass affects glucose metabolism, it plays a big role in someone’s risk of diabetes and cardiometabolic disease.

Anabolic resistance is a predictable involuntary biological phenomenon. It’s not a reflection of “lack of willpower” or bad dietary choices, though obviously lifestyle factors play a role.

The Institute of Medicine’s current guideline for protein intake, which is 0.8 g/kg/day, does not do a very good job of preventing sarcopenia in older adults, Skolnik told IHS participants. Even widely-recommended “healthy” diets like DASH, and Mediterranean, do not really address sarcopenia.

So how can you help your patients overcome the tendency to midlife weight gain? The simple answer is, increase protein intake.

Skolnik advises middle-aged women to eat at 25 grams of protein in each meal. For men, it’s 30 grams per meal. But this needs to be tailored to body weight. While 25 grams per meal will be sufficient to maintain muscle mass for a woman weighing 140 pounds, someone weighing 180 pounds will need roughly 33 grams of protein to obtain the same metabolic effect.

Protein for Breakfast

It’s not just the amount of protein that matters, it’s also the timing. Skolnik stressed that older people benefit from getting a big protein ‘dose’ early in the day.

Make sure that breakfast is protein-rich. Ideally, people should aim to eat around 30 grams of protein at each meal, evenly distributed throughout the day, but especially at breakfast.

Most people don’t do that. The average is about 10 grams at breakfast, 20 at lunch, and then a big 60-gram protein load at dinner. “The timing is all off,” she said.

All other factors being equal, it is more difficult for older people to push the physiological muscle-building ‘button’ than it is for younger people. It may seem paradoxical, but older people need more protein than younger people to build the same amount of muscle.

What do most Americans eat for breakfast? Cereal, oatmeal, croissants, muffins, bagels, and fruit. In other words, mostly carbohydrates, with very little protein. To overcome anabolic resistance, people need to flip that ratio by eliminating a lot of the morning carbs and including more protein-dense foods.

There are a lot of practical ways to do this. For example, a cup of Greek yogurt contains roughly 15 grams of protein. Top that yogurt with an ounce of chopped nuts, and you’ve just added another 7 grams of protein (plus healthy fats) to your breakfast.

Skolnik described the amino acid leucine as “the spark plug for muscle-building.” Consequently, older people should increase their intake of leucine-rich foods to at least 2 grams daily. Good leucine sources include: cod, salmon, tuna, beef, chicken breast, pork, duck, or turkey. For vegetarians and vegans, tempeh is an excellent source of leucine.

She acknowledged that it can be difficult for older vegans to get enough leucine, but it can be done. Nuts and nut butters are good animal-free sources, as are legumes such as chick peas, lentils, black beans, and kidney beans.

Fat Loss, Not Weight Loss

Many older people are, understandably, concerned with losing weight and they will often try a wide variety of approaches. Unfortunately, these well-intentioned efforts can end up working against them in the long run. Intermittent fasting regimens can be especially detrimental to older people.

“You want fat loss, not weight loss, and definitely not muscle loss,” Skolnik says. But unless someone is doing a lot of resistance exercise and building muscle while they’re following an intermittent fasting program, they’re very likely losing muscle, not fat. Yes, they’ll “lose weight” but it’s not the right kind of weight loss.

In their 2020 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine, Dylan Lowe and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, showed that lean muscle loss accounted for a shocking 65% of total weight loss from time-restricted eating programs.

Many older people are, understandably, concerned with losing weight and they will often try a wide variety of approaches. Unfortunately, these well-intentioned efforts can end up working against them in the long run.

This is doubly problematic: the muscle loss itself is detrimental, and when people stop the intermittent fasts and inevitably regain weight, it will be mostly fat, not muscle.

Variety is Key

Protein intake is a key factor in maintaining healthy muscle mass, but so are folate, B12, healthy fats, calcium, vitamin D and fiber.

Regarding the latter, Skolnik advises middle-aged people to increase fruit and vegetable intake as much as possible. And variety is as important, if not more important, than quantity. You want to give the body a broad spectrum of phytonutrients.

Aim to include two or three good sources of fiber in each meal. The goal should be 24 grams of fiber per day. “Most Americans don’t get anywhere near that much.” Avocados, apples, and nuts are excellent and versatile sources.

“Normal Weight” Obesity

Keep an eye out for patients with “normal-weight obesity.” These are the people with ‘non-obese’ BMI measurements, but significant loss of muscle mass.

“You can’t tell by looking, and you can’t tell from their BMIs. The issue is body composition. But currently there are no standardized measurements for detecting this.” Consequently, many such people go undiagnosed.

Skolnik estimated that roughly 30 million Americans fit this category. Metabolically they are at risk for many chronic conditions, despite their “normal” BMIs. It is important for clinicians to identify them, and then work with them to preserve and rebuild muscle.

Exercise to Capacity

All movement is helpful for elders. The degree to which someone can exercise will, of course, depend on overall functional status. For some 80-year-old people, climbing the stairs is a major accomplishment, while others are still able to take strenuous mountain hikes.

Keep an eye out for patients with “normal-weight obesity.” These are the people with ‘non-obese’ BMI measurements, but significant loss of muscle mass.

“Whatever someone is capable of, encourage that. Encourage more movement. It’s the key for independence in the advanced years.”

As a general recommendation, Skolnik suggests that middle-aged and older people engage in thrice-weekly sessions of strength/resistance training focused on all the major muscle groups, and including at least one set of 10-15 repetitions. It’s also good to include balance training activities such as yoga, tai chi, or dancing several times per week. For people who can handle it, moderate to vigorous cardiovascular/aerobic workouts are very beneficial.

“What you do now will determine your vitality 10 years from now. The more muscle mass you have going into your 7th, 8th, and 9th decades, the better your overall health will be,” Skolnik said.

END