Earlier this year, a game-changing study looking at the long-term health impact of dehydration gained the attention of CNN, NBC News, and other major media outlets.

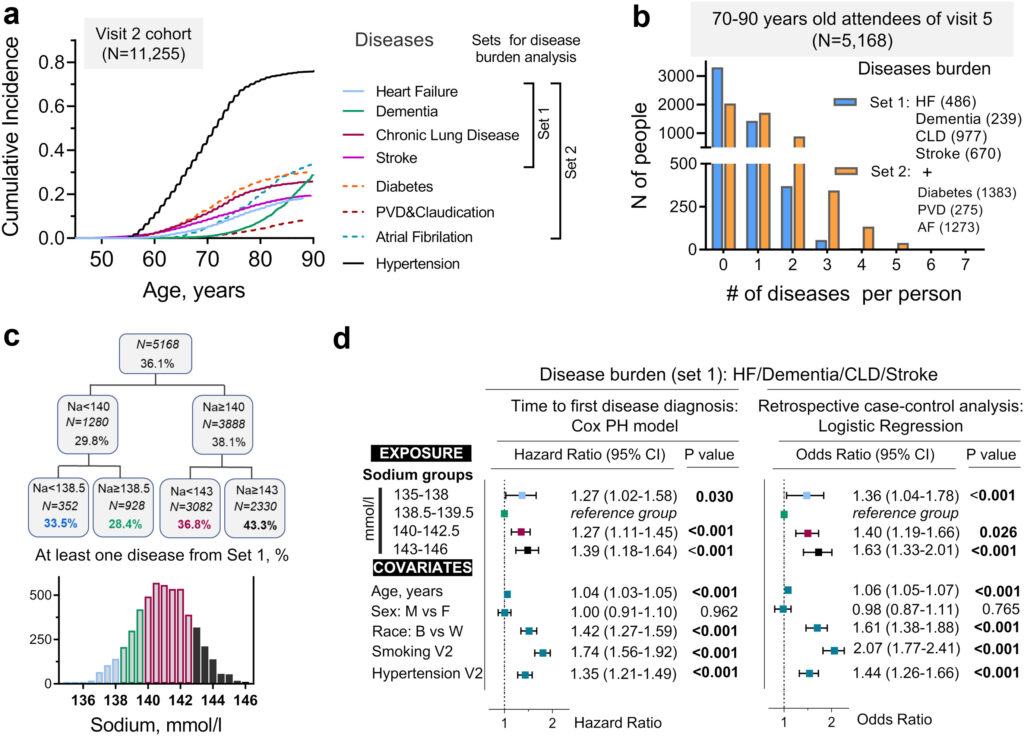

The massive project, part of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, followed over 11,000 individuals for 25 years, to test a hypothesis that optimal hydration may slow the aging process.

Using serum sodium level as a proxy marker for hydration level, the NHLBI researchers found that levels greater than 142 mmol/L–which indicate hypohydration–were associated with a 39% increased risk for chronic diseases, a 21% heightened risk of early mortality, and 50% higher risk of being physiologically older than chronological age.

In other words, serious health repercussions can result from simply not drinking enough water.

“People whose middle-age serum sodium exceeds 142 mmol/l have increased risk to be biologically older, develop chronic diseases and die at younger age,” writes lead author Natalia Dmitrieva, PhD, a researcher at NHLBI’s Laboratory of Cardiovascular Regenerative Medicine.

In their paper, Dmitrieva and colleagues explain that a person’s average serum sodium level during midlife (age 47-68 years) reflects individual hydration habits. The data showed that serum sodium in the range of 138–142 mmol/l is associated with lowest risk of chronic diseases and premature death.

It is ironic that so many people will eagerly jump at the latest “shiny object” health device, or app, or supplement when odds are they’d get far greater benefits from revisiting one of the essential foundations of life: water

“Since decreased body water is the most common reason for increasing sodium concentration, these results suggest that for people whose serum sodium exceeds 142 mmol/l, consistently maintaining optimal hydration may slow down aging process.”

It’s a striking observation, but it really should not be a surprise.

After all, the adult human body is 55-65% water, with most of that water (about two-thirds) stored inside the cells. People with more muscle mass relative to fat mass will have higher water content than those with a higher fat to muscle ratio. This is why, as a rule, women typically have lower total body water content than men.

A Common Problem

According to Dmitrieva and her team, more than 50% of people worldwide are not meeting their optimal fluid intake. Which means they are unwittingly putting themselves at increased risk for a host of chronic diseases and premature aging.

As people age, they have less total body water as a percentage of total body weight than they had during infancy or childhood. Typically, water accounts for roughly 75% of an infant’s total body weight. Among elderly people, that’s down to about 55% (Popkin BM, et al. Nutr Rev. 2010).

The reduction of body water with advanced age, together with a diminished thirst that typically occurs with aging, ultimately puts older adults–especially women–at risk for dehydration and its adverse consequences.

Water as Healing Modality

It is ironic that so many people will eagerly jump at the latest “shiny object” health device, or app, or supplement, or diet promising improved health and vitality, when odds are they’d get far greater benefits from revisiting one of the essential foundations of life: water.

Many do not realize that even minor degrees (<1%) of hypohydration, or uncompensated fluid loss, can impact cognition. Simply increasing one’s daily water intake has been shown improve cognitive flexibility (Khan NA, et al. J Nutrition. 2019).

Cellular health, and by extension, overall tissue health is inter-related with intracellular water dynamics. One recent study showed that tissue obtained from human breast and tongue tumors show very different intracellular water dynamics than their respective healthy surrounding tissues. That’s because water plays a fundamental role in maintaining normal cellular activity, cellular architecture, and biopolymer function (Marques MPM, et al. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2023).

While the general public may not be aware of the connection between hypohydration and illness, that’s not the case with committed health enthusiasts, who sometimes take their zeal for “hydration” to extremes. There’s plenty of chatter among fitness fanatics and biohackers about how much water to drink, the right type of water, the best electrolytes, the most effective water filtration system. There’s also a massive market for waters from around the world, as well as electrolyte drinks.

While it’s a good thing that health-conscious people recognize the importance of hydration, all the hype and controversy makes it difficult for many to parse out what is truly useful. And there’s also the challenge of avoiding the high sugar content of many of the popular hydration/electrolyte powders and beverages.

Drinking to Thirst?

Like so many things, a person’s water needs are highly individual, and we must address several important questions before we can help someone understand the optimal amount, type, and frequency of water intake.

The simple definition of dehydration is a situation in which more water is lost than is replaced, to a degree that compromises normal human function.

One school of thought suggests that healthy individuals should “drink to thirst,” or, in other words, only drink when they feel thirsty. That seems reasonable, based on the notion that as fluid volume changes, and the concentration of sodium and other osmolytes increases, the brain detects these changes and signals the appropriate fluid-seeking behaviors.

As people age, the sensation of thirst becomes less reliable as a guide for optimal hydration.

But this guidance is increasingly subject to debate as the science of thirst mechanisms continues to evolve. We now know that over the age of 50, the body’s intrinsic ability to sense the need for water is diminished. There are multiple studies showing that otherwise healthy older individuals drink less frequently than younger people, despite increased serum osmolality (McAloon Dyke M, et al. Geriatr Neprhol Urol. 1997).

In other words, as people age, the sensation of thirst becomes less reliable as a guide for optimal hydration.

In natural medicine, people are often told to drink “Half your body weight in ounces.” Therefore, if a person weighs 150 pounds, s/he should drink 75 ounces of water every day.

It’s a good general guideline, but it is not nuanced to the specific needs of an individual. It’s one reason why there are no strongly enforced public health guidelines of how much water people should drink.

Ranges of 2.7-3.7 liters daily have been suggested by various experts and organizations, with additional intake for those who lose more water than the average person, such as marathon runners, for example. But again, these are just general guidelines, not hard and fast rules.

An athlete can lose 6-10% of body weight in sweat during a vigorous prolonged event. Even modest amounts of dehydration (-2% body mass) can negatively impact physical performance. So, people who work out vigorously or participate in exertive activities need to be extra mindful of their water intake.

But activity level is just one factor in the water balance equation. Age is another important one. Older adults need to be more conscientious, as they can easily become dehydrated. Conversely, they can easily become hyponatremic with excessive water intake. This is often due to the use of pharmaceuticals that deplete sodium.

It can be tricky to ensure that elders stay well-hydrated without becoming hyponatremic.

How We Lose Water

Most people think of losing water through urine via the kidneys. However, we also lose water through the skin, lungs, and gastrointestinal tract. We can lose water and sodium together (referred to as “isotonic water loss”) through burns, diarrhea, sweating, vomiting, low aldosterone, and high blood sugar levels.

If we lose more water than sodium (“hypertonic water loss”), such as through fever and increased respiration, serum sodium will increase. And this, as was so elegantly shown in the Dmitrieva study, can compromise overall health if it persists.

On the other hand, if we lose too much sodium (“hypotonic water loss”), especially via diuretic drugs, there will be an imbalance at the other extreme which can also be problematic.

There are many different aspects to the seemingly simple problem of dehydration. It’s not just about losing water, it is about the loss of a healthy balance between water, sodium, and other electrolytes like potassium.

Who is most susceptible to dehydration?

- People who do not have regular access to clean drinking water—a surprisingly common phenomenon here in the US— or who are not drinking enough for their bodily needs

- Those exposed to high temperatures (e.g., summer months, arid southern climates, saunas)

- Athletes and others who are highly active physically, and who lose a lot of water through sweat

- Those losing water through diarrhea (of primary importance in children)

- Those prone to kidney stones or urinary tract infections

- Immobile elders, and those with impaired thirst mechanisms due to diabetes and kidney disease

- People who experience frequent air travel and jet lag

Tests and Markers

There is no single well-validated “gold-standard” test for dehydration. Consequently, measurements of serum and plasma osmolality can serve as indirect indicators. Additionally, lab tests for kidney function, like blood urea nitrogen (BUN), can be also useful in determining whether someone is dehydrated.

A Cochrane review published in 2015 assessed other commonly-used tests for dehydration, including bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), urinary measures (specific gravity, osmolality, voids, volume), and tests of saliva and tears. The overall takeaway was that no particular assessment or combination of these assessments seemed to adequately identify dehydration.

Even though there is no definitive simple test, there are a number of important physical symptoms and signs: hypotension, tachycardia, fever, fatigue, dry mucosa, headache, constipation, skin tenting, and even cracked lips. While none of these are absolutely reliable, someone exhibiting several of them simultaneously is very likely to be under-hydrated.

With the rise in self-monitoring apps, devices, and other technologies, it would seem that more sophisticated sensors and detection methods will emerge in the future.

What Counts as Hydration?

One of the first aspects of rehydration is to know what actually counts as hydration.

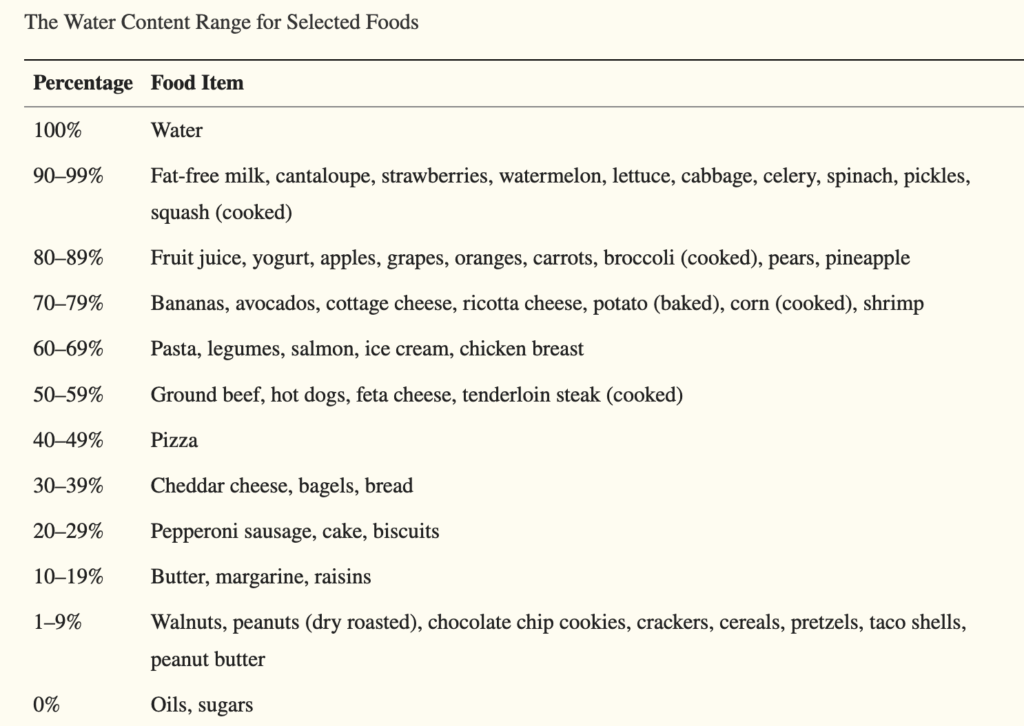

In principle, total daily fluid intake represents the sum of all beverages (e.g., water, tea, coffee, juices, wine or beer, etc) as well as all foods consumed daily. But foods have varying amounts of water, so it can be tricky to estimate the amount of water someone gets from food. High quantities of water (~75-100%) are found in fruits, vegetables, soups, and broths, with lesser amounts found (~0-50%) in nuts, meats, breads and cereals.

When it comes to drinking water, the best choice is purified water without chemical or microbial contaminants.

Recent research indicates that microbes in ordinary tap water can alter the gut microbiome, and the source of water (bottled, tap, filtered, or well water) can significantly modify the gut microbial diversity.

Some functional medicine practitioners advise patients to have their home water tested by a water testing laboratory to ensure it is free of heavy metals, microorganisms, and other toxic offenders such as persistent organic pollutants. If these tests do detect contaminants, patients will be faced with the challenge of how to remedy the problem.

For a variety of reasons, many people choose to drink bottled water. Indeed, total revenue generated from the sales of bottled water are projected to top $94 billion this year. The bottled water industry is expected to grow by an annual rate of 6.3% over the next four years.

Buyers often assume that bottled water is more pure than the water from their taps. That might be true, but it is not guaranteed. And water that comes in plastic containers often contains endocrine-disruptive compounds. For people who prefer bottled water, stainless steel or glass containers are the better choices. for on-the-go refills.

A lot of people use reverse osmosis filtering systems for their home tap water. But these systems remove a lot of minerals along with the toxins. So, people using these systems need to pay closer attention to their mineral balance and, in some cases, augment their mineral intake through mineral-rich foods and/or supplementation.

Early morning “wake-up strokes” account for up to 25% of all strokes. It may be tempting to attribute that risk to stress responses to the alarm clock. In reality, it might have more to do with hypohydration.

The Sodium Question

Some holistic physicians, nutritionists, and naturopaths advise patients to add things like fresh-squeezed lemon juice, a dab of honey, or a spoonful of crystal salt to their water, based on the idea that doing so will increase water uptake and utilization.

The use of mineral-rich Himalayan pink crystal salt to make sole (pronounced “so-lay”) water has become popular in recent years.

The connection between water and sodium cannot be separated when it comes to discussing dehydration, considering that water follows the path of sodium/salt (osmotic effect). So, there is a general principle to support the notion that drinking sole water will improve hydration, though there are no definitive studies to prove this.

Not surprisingly, though, there is considerable controversy about intentionally adding sodium to water, considering how pervasive it is in processed foods, and even in many “healthy” foods.

The topic of sodium intake is constantly being revisited in the scientific literature. In a 2021 paper on the subject, a team of Canadian researchers reviewed the current global literature on sodium intake and cardiovascular risk. They concluded that “it is reasonable, based upon prospective cohort studies, to suggest a mean target of below 5 g/day.” (Mente A, et al. Nutrients. 2021).

The authors add that people whose daily sodium intake is in the 3-5 g range generally have lower risk of cardiovascular events than those who consume over 5 g daily. They contend that there’s no clinical data proving that reducing daily intake below 2.3 g will confer any further risk reduction.

For people who do use salt in their cooking or as an additive to make sole water, it is important to consider the source of the salt. Products may differ greatly in their procurement and composition. Many mass market salt products are bleached and stripped of their minerals.

I personally choose Original Himalayan Crystal Salt® because it has been analyzed and found to contain 84 trace minerals. Unpublished pilot studies done by Barbara Hendel, MD, author of the book, Water and Salt: The Essence of Life, suggest that Himalayan Crystal Salt may have better hydration and health effects than table salt.

A Morning Ritual

It is notable that the risk of acute ischemic stroke is highest in the early morning hours. These so-called “wake-up strokes” account for up to 25% of all strokes. It may be tempting to attribute that risk to stress responses to the alarm clock or reluctance to get up and face another day at work. In reality, it might have more to do with hypohydration.

When people wake up, it’s typically after anywhere from 6-10 hours of sleep during which they had zero fluid intake. Though there are not yet any clinical studies to prove it, it makes good sense to start one’s morning routine with a glass of water.

My personal morning ritual includes starting the day with an 8-12 ounce glass of room-temperature spring water, with a teaspoon of sole (diluted Himalayan Crystal Salt), soon after rising, about an hour before breakfast.

I also drink a variety of herbal teas throughout the day, incorporating different types to provide a range of phytochemicals. After all, many centenarian “Blue Zones” regions punctuate their day with tea, typically green tea, and sometimes coffee, and wine.

There are mixed reviews about whether caffeinated coffee or other beverages like black tea dehydrate the body. On the one hand, people who drink coffee and black tea tend to drink a lot of it, which increases fluid intake. On the other hand, caffeine has a diuretic effect.

There’s no clear-cut “good vs bad” answer here. Rather people should strive to find a healthy balance between coffee or tea, and other types of beverages that provide a diverse array of nutrients and phytochemicals.

Some people wonder about drinking water at meals. While there is no firm science to prove it, it seems logical that drinking too much water before meals could dilute digestive secretions and prevent healthy digestion.

People who wake up frequently during the night to urinate, are wise to consume the greater portion of their total fluid intake during the day, and to avoid drinking a lot before bedtime. Sleep is so important for overall health, and chronic interruptions because of the need to urinate can be detrimental over the long term.

END

Deanna Minich, MS, PhD, CNS, IFMCP, is a nutrition scientist, international lecturer, teacher, and author, with over twenty years of experience in academia and in the food and dietary supplement industries. She is the author of six consumer books on wellness topics, four book chapters, and fifty scientific publications. Her academic background is in nutrition science, including a Master of Science in Human Nutrition and Dietetics from the University of Illinois at Chicago (1995), and a Doctorate in Medical Sciences (nutrition focus) from the University of Groningen in the Netherlands (1999). For a decade, she was part of the research team led by the “father of Functional Medicine,” Jeffrey Bland, PhD, and has served on the Nutrition Advisory Board for The Institute of Functional Medicine. Dr. Minich is Chief Science Officer at Symphony Natural Health.