If 2018 was a landmark in the history of hemp and cannabis in the US, 2019 is shaping up to be equally important, as the FDA and other federal agencies reckon with a hemp-related industry that is now generating billions of dollars and a significant number of business opportunties large and small.

Last year, the FDA approved Epidiolex, the first naturally-occurring prescription drug derived from cannabis.

Shortly thereafter, Congress passed the Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018—aka the Farm Bill–that included a mandate to legalize at the national level, the cultivation, processing, and commercial use of “industrial hemp,” as distinct from “cannabis.”

Under the new law, the definition of hemp is: “Cannabis sativa L, or any part of that plant, including seeds, derivatives, and extracts, with a delta-0 tetrahydrocannabinol  (THC) concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

(THC) concentration of not more than 0.3 percent on a dry weight basis.”

The Farm Bill forced the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) to reclassify low-THC hemp, moving it out of its former designation as a Schedule I controlled substance (drugs of abuse with no accepted medical use and lack of safety) to Schedule V (low potential for abuse, accepted medical uses).

To many cannabis advocates, these steps represented a legitimizing moment: the federal government has recognized true therapeutic and economic potential in this long-criminalized plant. Many see the Farm Bill as a major win for health freedom.

But it’s not so simple. While the Farm Bill does legalize industrial use of low-THC hemp, it does not legalize cannabis that contains higher amounts of THC. Nor does it legalize the promotion of cannabis-derived compounds such as CBD in foods, beverages, or dietary supplements. The exception is hemp seed, which is high in omega-3s, but does not contain CBD, THC, or other cannabinoids.

Anything that contains CBD, THC or any other cannabinoids, and has not gone through the FDA’s drug approval process remains, technically, an unauthorized pharmaceutical. The Farm Bill does not change that.

Many legal experts in this field say the industry is vulnerable to regulatory action at both the federal and state levels. There’s also the possibility of class action lawsuits from plaintiff’s attorneys.

FDA Rules Still Hold

“The Farm Bill was very important. As long as something is derived from hemp that has less than 0.3% THC, then it won’t be considered a Schedule I controlled substance. That’s a huge deal,” says Justin Prochnow, an attorney with Greenberg Traurig, a corporate law firm with extensive experience in the natural products space.

In an interview with Holly Lucille, ND, on the Natural Partners website, Prochnow explains that the Bill makes it much easier for businesses to develop hemp-based products for a variety of uses. But he stressed that the Bill “has no effect on how the FDA regulates CBD.”

And therein lies the rub.

Immediately after the Farm Bill was signed, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb–who stepped down earlier this month— clarified his agency’s position in no uncertain terms:

“It’s unlawful under the FD&C Act to introduce food containing added CBD or THC into interstate commerce, or to market CBD or THC products as, or in, dietary supplements, regardless of whether the substances are hemp-derived. This is because both CBD and THC are active ingredients in FDA-approved drugs and were the subject of substantial clinical investigations before they were marketed as foods or dietary supplements.”

The agency argues that CBD was not routinely used as a dietary ingredient prior to 2005, when GW Pharmaceuticals—the company that developed Epidiolex—had filed an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to develop CBD as a prescription drug.

FDA’s rules are such that unless there’s a well-established history of use as a nutritional ingredient, a naturally derived substance once registered by a drug company for drug development cannot be used for non-Rx purposes.

“If an ingredient is the subject of an IND, then you cannot turn around and use it in a food, beverage, or supplement product, if it wasn’t first used in a food, beverage or supplement before the IND,” explains Prochnow.

“If an ingredient is the subject of an IND, then you cannot turn around and use it in a food, beverage, or supplement product, if it wasn’t first used in a food, beverage or supplement before the IND,” explains Prochnow.

The FDA acknowledges that there is actual medicinal value in cannabis-derived compounds, but it wants to see them developed and marketed as prescription drugs. Gottlieb stresses that there are “pathways” for companies to seek FDA approval to market cannabinoid drugs based on well conducted clinical studies.

He also hinted that there are circumstances in which certain cannabis-derived compounds might be permitted in foods or supplements. “Although such products are generally prohibited to be introduced in interstate commerce, the FDA has authority to issue a regulation allowing the use of a pharmaceutical ingredient in a food or dietary supplement. We are taking new steps to evaluate whether we should pursue such a process.”

Late in February, Gottlieb told the House Appropriations Committee that the FDA will hold its first public hearings on CBD regulations. The first major public hearing on the issues will be held on May 31—“to obtain scientific data and information about the safety, manufacturing, product quality, marketing, labeling, and sale of products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds.”

The commissioner indicated that the agency might develop two regulatory standards based on dose-levels: a more stringent framework for products with high concentrations of CBD, and a less-stringent one for low-concentration formulas to be used in foods or supplements. But Gottlieb also warned congress–as well as industry and the general public–that development of new CBD regulations will not be “straightforward.”

The Claim Game

But even if FDA were to modify its rules on non-Rx CBD supplements, the agency would take issue with many of the product claims.

Under the Dietary Supplements Health Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, supplement makers are only permitted to make “structure-function” claims. They cannot make—or imply–claims about preventing, treating or mitigating disease states. Gottlieb points out that CBD and other cannabis-derived products are promoted for treatment of cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric disorders, diabetes, and other diseases—all of which are clear violations of DSHEA.

On paper, at least, Gottlieb holds a hardline stance: “We’ll take enforcement action needed to protect public health against companies illegally selling cannabis and cannabis-derived products that can put consumers at risk and are being marketed in violation of the FDA’s authorities.”

In practice, however, enforcement has consisted of nothing more than warning letters informing CBD manufacturers that they are out of bounds.

The reality is that the FDA’s budget and personnel are stretched thin, and the agency was hobbled by the government shutdown in January. Even in the best of times, it faces many conflicting demands on its limited resources. And it currently operates under an Executive branch with a decidedly anti-regulatory mindset.

Bottom line is, restricting consumer access to wildly popular products that generate massive revenue, create jobs, spark a lot of Wall Street action, and don’t really hurt anyone is not a top priority for the FDA at the moment.

But that could change.

Attorney Todd Harrison, a partner with Venable, LLP, who specializes in supplement industry law, believes it’s only a matter of time before the agency decides to put  some bite in its bark.

some bite in its bark.

A Paper Tiger?

“The FDA cannot keep issuing warning letters and not eventually take action. The agency is not doing itself, nor the industry any favors by doing that,” Harrison told Holistic Primary Care in an interview.

Failure to follow through with meaningful regulatory action sends a message that the agency is, essentially, a paper tiger that need not be taken seriously. That, says Harrison, invites all sorts of abuse in an industry already plagued by ingredient adulteration, misleading marketing, and fly-by-night operators.

Harrison added that many companies have shifted their marketing messages away from overt language about CBD, focusing instead on terms like “full spectrum hemp oil” or “whole plant hemp extract.”

These terms currently have no legal or regulatory definition, and they may keep companies temporarily safe from FDA scrutiny. But the bottom line is that if the product contains significant quantities of CBD, it is still technically an unapproved drug by the strictest interpretation of FDA statutes.

Prochnow says that when thinking about the current rules about CBD, it is best to talk about whether or not it is “permissible” rather than “legal.”

State by State Action

The Fed may not be taking hard action against cannabinoid-containing products, but some states are certainly doing so. It is at the state level where things get really complicated.

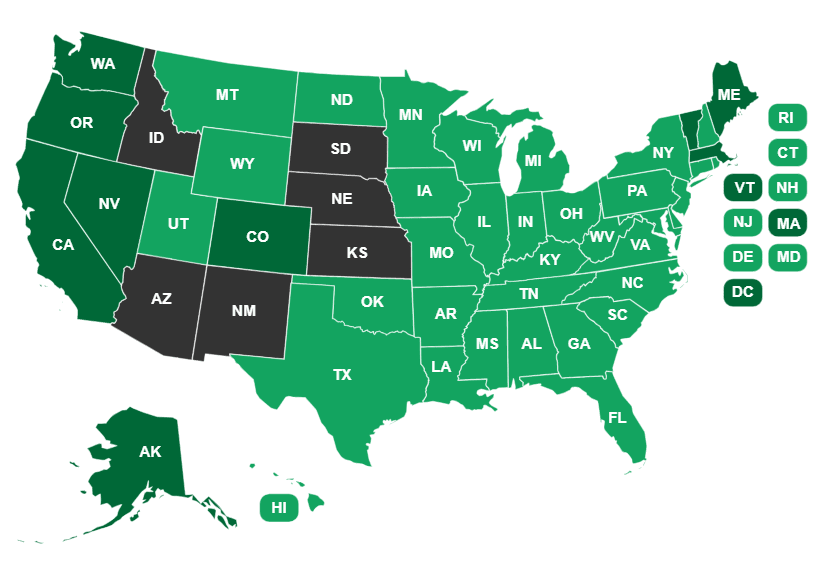

The states vary widely in their laws about cannabis. Currently, 33 states and the District of  Columbia have legalized THC-containing cannabis for medical use, and 11 now permit access to cannabis without a doctor’s prescription or recommendation.

Columbia have legalized THC-containing cannabis for medical use, and 11 now permit access to cannabis without a doctor’s prescription or recommendation.

Fourteen states permit, at least to some degree, the use of low-THC products—basically CBD—but still prohibit cannabis containing greater than 0.3% THC. But even in states where low-THC, high-CBD products are officially permitted, there remains a threat of regulatory action, as is underscored by a recent crackdown in Texas.

Trouble in Tarrant County

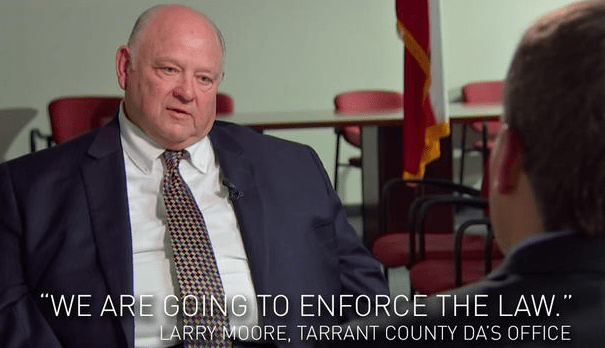

Early in February, law enforcement officers in Tarrant County (Ft. Worth), began arresting individuals possessing hemp-derived CBD products, on grounds that non-Rx CBD is still illegal in the state, even if the product contains THC levels under the 0.3% threshold defined by the Farm Bill. The county’s District Attorney considers possession of any amount of THC a felony. Charges can result in jail time. Possession of THC-free CBD is a misdemeanor, unless someone has epilepsy and a prescription for Epidiolex.

In comments published in the Star Telegram, a Fort Worth paper, defense attorney David Sloan noted that, “Tarrant County will prosecute THC and this is happening in a lot of other Texas counties,” he said.

Sloan says that the Texas legislature is considering a move to legalize industrial hemp (under 0.3% THC) and bring the state into accord with the federal Farm Bill. But until that happens, county DAs are within their jurisdiction to prosecute THC possession.

News reports indicate that the intent to prosecute varies county-by-county in Texas.

Many natural medicine advocates decry the Texas actions as a gross miscarriage of justice. It is notable that Tarrant County law enforcement is arresting individuals, but so far has not targeted CBD retailers, though it has issued warnings.

Jonathan Miller, an attorney for the US Hemp Roundtable, an industry advocacy organization, has urged the Tarrant County DA to stand down.

In a formal letter to the DA’s office, Miller notes, “Texas law is undeniably unclear about the status of hemp-derived CBD. There is no explicit prohibition for the retail sale of such products, nor admittedly is there any express permission for its sale. Indeed, there is no definition of “hemp” under Texas law.”

He adds that while marijuana and THC are generally considered controlled substances under Texas law, there are provisions for exemption in the case of substances that are “specifically excepted.” Miller and the Hemp Roundtable contend that low-THC hemp-derived products, as defined by the 2018 Farm Bill, represent such exceptions.

Regional Clampdowns

Late last year, the Ohio Pharmacy Board took a position that CBD is a “derivative of Marijuana” regardless of whether it was extracted from hemp or cannabis. The state has ruled that CBD oil, like all other “marijuana products” can only be dispensed in licensed medical marijuana dispensaries, of which there are 56 in the state.

Prochnow notes that California, despite its generally permissive cannabis rules, issued a policy statement prohibiting the use of CBD in foods or beverages. So far, there have been no actions to enforce this. But that could change at any time.

Also in February, the Maine Department of Health sought to rein in CBD by restricting sales of orally-ingested CBD products only to state-certified medical marijuana dispensaries, and only to registered patients.

The same week, the New York City Department of Health began a clampdown on restaurants, bars, and coffee shops that use CBD in foods and beverages. The Big Apple became the first major city to take action, but other cities—including Los Angeles—may be considering similar moves.

Given the size and scale of the non-Rx CBD market, these local regulatory actions are not likely to make a dent in the industry’s growth. And with the FDA demonstrating a general lack of intention to block these products, it seems that for the foreseeable future, CBD will be “permissible” across most of the country if not fully “legal,” to use Prochnow’s terminology.

Given the size and scale of the non-Rx CBD market, these local regulatory actions are not likely to make a dent in the industry’s growth. And with the FDA demonstrating a general lack of intention to block these products, it seems that for the foreseeable future, CBD will be “permissible” across most of the country if not fully “legal,” to use Prochnow’s terminology.

But class-action lawsuits could kill the buzz.

So far, there have been a few class action suits filed against cannabis companies, mostly related to matters of business conduct (violations of federal securities law, employee abuse, investor relations issues).

But some industry-watchers say the field is vulnerable to suits alleging harm to health and wellbeing owing to unsubstantiated or misleading advertising claims about the benefits of CBD or other cannabis-related products, or to injury caused by contaminants in these products.

None of that has happened, but it could.

Implications for Practitioners

Do practitioners who recommend or dispense CBD or other low-THC hemp products face any legal or regulatory risk?

It’s a big question with no clear-cut answer.

Generally, the FDA has shown little inclination to involve itself in overseeing the practice of medicine. Passage of the Farm Bill and the DEA’s reclassification of hemp means there’s very little risk of federal agents showing up at doctors’ offices in riot gear.

In a recent alert about cannabis, hemp and CBD regulations, the law firm of Wilson, Sonsini, Goodrich & Rosati (WSGR) notes that, “the federal government could not revoke a physician’s license to prescribe a controlled substance solely because the physician “recommended” the use of medical marijuana to a patient. The court also held that the federal government could not conduct an investigation that could lead to revocation where the basis for the government’s action is solely the physician’s professional “recommendation” of the use of medical marijuana.”

The WSGR attorneys note that this position is based on the notion that a physician’s recommendation is an expression of free speech and protected by the free speech provisions of the First Amendment. Further, the dispensing of information—or a “recommendation” concerning a controlled substance—is different than the dispensing of controlled substances.

So, there’s relatively little risk of federal-level action against practitioners.

At the state level, however, it’s less clear-cut. As noted above, states vary widely in their statutes on cannabis in general and CBD in particular.

Clinicians recommending CBD to their patients, or making it available in their clinic dispensaries would be wise to thoroughly familiarize themselves with their states’ specific statutes, and more importantly, with the political “climate” in their states regarding cannabis in general, and CBD specifically.

While the risks are probably very low, they are not non-existent. It is smart to do your homework.

END