“Food produced using animal cell culture technology.” That’s what the Food and Drug Administration calls it. It also goes by:

“Food produced using animal cell culture technology.” That’s what the Food and Drug Administration calls it. It also goes by:

- in vitro meat

- cellular agriculture

- lab-grown meat

- cultured meat

- clean meat

- meat without slaughter

It’s a mouthful by any name. Call it what you will, tissue cultured meat is closer to market than it has ever been. It may very well find its way to the nation’s dinner plates by year-end, according to presentations at a recent FDA public hearing on the safety and feasibility of clean meat.

At the table: FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb and a host of interested parties, including food safety agencies, animal rights organizations, beef industry big shots, and food tech visionaries.

Culturing food is not cutting-edge. In fact, it is age-old. Think yogurt and sauerkraut. What makes clean meat innovative is the production method and the medium.

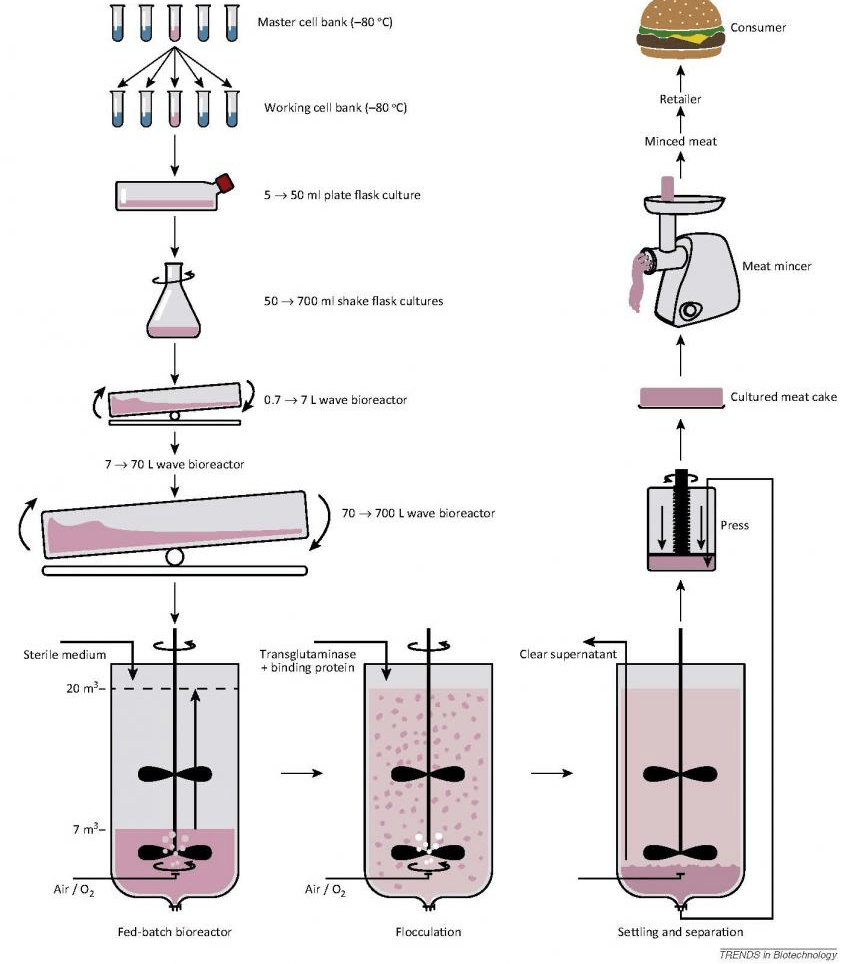

The process, with a patent that goes back more than 20 years, is very much like that used to produce stem cell treatments in medicine. It involves taking stem cells from the muscles of a cow, sheep or other animal, and growing the cells in labs. The cells, or myoblasts, fed on the very fats, carbohydrates and amino acids that animals need to thrive, replicate trillions of times over, creating strands of muscle tissue.

But instead of being used for disease treatment, these tissues can be used as dinner.

It’s all very interesting, and has huge implications for the massive agribusinesses that currently dominate meat production. But the FDA has many questions. As a healthcare professional–and a potential consumer of this meat-by-any-other-name, so should you.

Is It Really Happening?

US industry leaders including Memphis Meats, Just (formerly known as Hampton Creek) and Mosa Meat are producing a ground or pastelike product — clean and cruelty-free Spam, if you will — alleged to be market-ready by the end of the year.

to be market-ready by the end of the year.

Alternative meat — another term! — with a complex tissue structure that replicates the marbling of animal muscle tissue and fat— is in R&D stage at Israel’s Aleph Farms.

Innovators already have their sights on developing designer meats with a different fat profile, lower in saturated fat and cholesterol, and with higher Omega-3 fatty acids than conventionally farmed meats.

So, yes, it is really happening.

Is It Really Meat?

Not according to the U.S. Cattlemen’s Association. They’ve filed a petition with the USDA, requiring the terms meat and beef to refer exclusively to livestock raised and slaughtered for consumption.

Thanks to the rapid rise of plant-based cuisine, terms like nut meat and coconut meat are appearing in the mainstream lexicon, as well as on menus nationwide.

A very similar debate has happened in the milk world, with the dairy industry lobbying hard—and sometimes successfully—to prevent commercial use of terms like “soy milk” or “almond milk” on grounds that “milk” should be defined strictly as having mammalian origins.

“The idea in the meat industry that you have to slaughter animals for something to be considered meat doesn’t make any sense,” argues Matt Ball, spokesman for the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit advocating for plant-based and clean meat innovation. GFI prefers the term clean meat, asserting it’s cleaner to produce and cleaner for the environment.

Wide adoption of these types of products would obviate the need to raise and slaughter billions of animals, thus providing an option for carnivores who want to eat meat but abhor the cruelty inherent in current systems for producing animal-based foods.

Advocates like Ball assert that clean meat is pure animal protein, and of potentially higher nutrient density than many of the foods in today’s grocery stores.

That said, in terms of texture and structure, today’s state of the art clean meat products are still nowhere near what a meat-eater would expect from a prime rib or a lamb chop.

Is It Safe?

The term “clean meat” doesn’t sit too well with the meat industry, the implication being that slaughtered livestock is dirty. The truth is, there’s something to implication. Among the health risks posed by conventional meat production:

- Slaughterhouse contamination, resulting outbreaks of E coli , Salmonella, Listeria and other bacteria in meat sold for consumption According to the CDC, 48 million Americans contract food-borne illnesses each year.

- Contaminated water and soil from manure runoffs, resulting in fish kills and toxic algae blooms that threaten fresh water supplies and marine ecosystems.

- Antibiotic overuse: Factory farm operations routinely use massive quantities of antibiotics to keep animals relatively disease-free despite overcrowded conditions, and to promote growth. Animal agriculture accounts for 80% of all antibiotic sales and consumption.

According to the Consumer Union and American Medical Association, this overuse of antibiotics poses a human risk, creating antibiotic resistant diseases, aka superbugs. Back in 2001, the AMA declared that it is “opposed to antimicrobials at non-therapeutic levels in agriculture, or as pesticides or growth promoters, and urges that non-therapeutic use in animals of antimicrobials (that are used in humans) should be terminated or phased out.” That hasn’t happened.

On the other side, clean meat production:

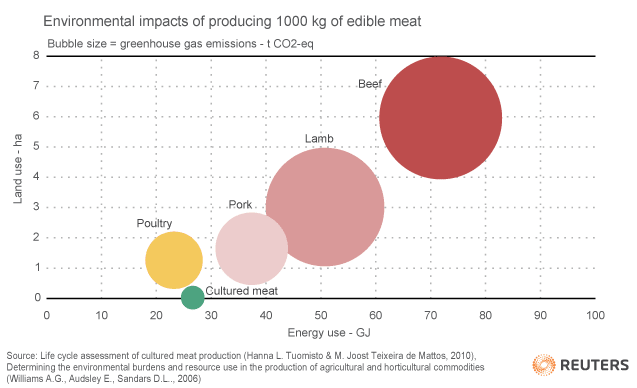

- Requires much less water and land

- Produces no runoff contamination risk

- Drastically reduces the amount of greenhouse gases produced as a byproduct of feed lot operations involved in current meat production.

But these Brave New Burgers are not without their own issues, concerns, and unknowns, including:

- Cell line cross-contamination risk, especially at “critical control points”

- Energy use — production requires energy, studies vary on how much

- Spoilage and storage conditions: It is unclear how common food-borne pathogens will interact with tissue cultured meat compared to meat from conventional meat production

- Questions about digestibility and metabolism: This technology is very new, and there are many unknowns about how humans will digest, assimilate, and metabolize cultured tissues as compared to meat derived from slaughtered animals

Will “Mikey” Like It?

“Our meat is meat and our chicken is chicken,” asserts Erick Schultz of Memphis Meats. Well, yes and no.

Part of the pleasure of food is the terroir, the taste of how and where it’s grown — a luscious just-picked strawberry being the textbook example. Some carnivores would say that there is a similar phenomenon with meat: the quality and flavor depend on where and how the animals are raised.

What can we expect of a lab-grown product? No one but the company founders really knows yet. There are no commercially available products yet, and the relatively few people who have actually tasted clean meat are industry professionals, most of whom are involved in R&D.

No doubt some consumers will struggle to overcome what food industry insiders call the “Ick Factor.” This refers to a reflexive disgust at the very idea of a meal produced in a lab. It sounds creepy and unnatural, and therefore unappealing.

But the truth is, conventional livestock production and slaughter is icky, too.

According to a recent poll, Americans are increasingly uneasy about the health and ethical implications of conventional meat production. They want transparency within the meat industry. Katy Keiffer, a former chef and butcher says, “People are scared and they want to learn.”

Clean meat industry leaders are betting on the possibility that ethical motivations, health and environmental concerns, or sheer curiosity will create a large enough market of people willing to overcome the Ick Factor, and give cultured meat a try.

Is It Economical?

Currently, a clean burger costs about $6,000. Make it $7,000 for a clean fish cake.

So the answer to this question is definitively, “Not yet!”

The cost is the real deal-breaker right now, says Keiffer, author of What’s the Matter With Meat? and host of Heritage Radio’s podcast series What Doesn’t Kill You.“ I don’t see the price coming down enough,” she says. “Consumers want cheap meat. I’ll be surprised if it comes close to getting market share.”

But successful startups built around leading edge technologies are a powerful magnet for venture capital. Bill Gates and Google co-founder Sergey Brin are pumping millions into clean meat technologies.

So are Tyson Foods and Cargill, two of the largest meat processing companies, working to hedge their bets against possible market upset. Most recently, drug giant Merck has gotten into the clean meat game, with an $8.8 million investoment in Dutch clean meat company, Mosa Meat (see sidebar).

Is It Necessary?

Impossible Foods, Beyond Meat and other plant-based protein innovators have created plant-based products so satisfying in terms of flavor and texture, they’re surging in popularity and market share. These are meat-like products completely derived from vegetable materials that have been restructured to look, feel, and taste like meat. No cow, no cholesterol, no guilt.

Do we really need to pursue food from animal cell technology when we can accomplish the same goal with readily available ingredients like peas, beets and coconut?

Apparently we do.

Despite the popularity of plant-based alternatives like the bleeding (but bloodless) Impossible Burger, meat consumption is skyrocketing in developing countries like India and China, though America remains #1 in total per capita meat consumption.

The world’s population is forecast to hit 10 billion by 2050. With so many people to feed, and all relying on limited resources, Jonathan Porritt of UK’s Green Party considers meat consumption our greatest risk to sustainability.

The Good Food Institute is pushing for lab meat because the global stakes are so high. “We have to pursue every possible solution in the face of soaring meat consumption,” says Ball.

Would Ball, a longtime vegan, eat clean meat? “Oh, yes, yes,” he says. “Absolutely.”

Who’s Regulating Clean Meat?

At the moment, it’s the FDA, which oversees 80% of food. But stay tuned. The US Cattlemen’s Association has lobbied to have clean meat regulated by the USDA.

But the truth is, neither federal regulatory agency has developed oversight protocols that are able to keep pace with this emerging food technology. The FDA or other federal food oversight agencies need to step up their efforts to develop definitions, guidelines and regulatory protocols, because this industry shows no sign of slowing down.

Until September 25, 2018, the FDA is accepting public comment and fielding questions about the safety and viability of clean meat (Submit your remarks to the FDA).

In summary, clean meat is a fast-evolving technology that offers both opportunities and challenges.

It could potentially allow consumers to eat safer, healthier, slaughter-free versions of the meat many crave.

It could provide more food to feed our soaring population, while simultaneously dialing down the heavy environmental impacts of conventional meat production. It may also be safer, with less risk of slaughterhouse contamination and food-borne pathogens.

However, the safety of clean meat both in terms of production and consumption is largely unknown, and there is not yet any clarity on how or by whom this burgeoning industry will be monitored and regulated.

If it does catch on and goes mainstream, tissue cultured meat could have a massively disruptive effect on the entire animal agriculture industry. That means many people currently working in any aspect of raising, slaughtering, and processing livestock will have to find different jobs.

For the near future, product affordability will be a major obstacle to mainstream acceptance. It remains to be seen whether–after all the effort, investment, and expense to produce cell-cultured meat–Americans will trust it, buy it, and eat it.

But we are clearly on the threshold of an entirely new approach to cultivating animal-derived foods. What sounded like Sci-Fi a decade ago is rapidly approaching market-ready status.

The upcoming Good Food Conference explores all these and other food-related issues.

Comments/questions about the safety of clean meat? Submit your remarks to the FDA. Deadline: September 25, 2018.

END