On March 6, New York Times subscribers came upon a full-page open letter—in print and online– from the popular snack food company Clif Bar, challenging competing brand, KIND, to live up to its name and go completely organic.

On March 6, New York Times subscribers came upon a full-page open letter—in print and online– from the popular snack food company Clif Bar, challenging competing brand, KIND, to live up to its name and go completely organic.

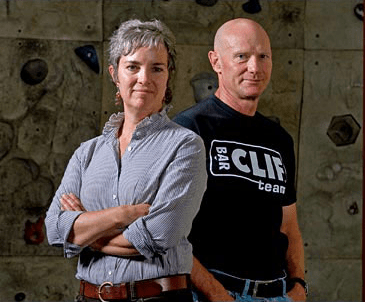

Clif founders and co-CEOs Gary Erickson and Kit Crawford, are outspoken advocates for organic agriculture, environmental stewardship and corporate responsibility. Organic agriculture is, “good for people, farmers, communities and the planet,” they wrote in their open “invitation” to KIND.

Clif states that the company made the organic shift back in 2003, that currently 76% of its ingredients are organic, and that it is aiming for 100% in the next few years.

A commitment to organic is, “the best move a food company can make for people and the planet,” say Clif’s founders as they urged KIND to, “do a truly kind thing and make an investment in the future of the planet and our children’s children.” Clif has even promised, “to help them, our largest competitor, by lending our expertise.”

Clif touts the fact that the company recently purchased “our billionth pound of organic ingredients,” and claims to be the largest private funder of research on organic agriculture.

Despite stellar growth in consumer demand over the last decade, organic foods represent no more than 5% of total US retail food sales, according to Clif Bar.

“If Clif Bar and KIND—the two largest nutrition bar companies in the country—joined hands, the impact would be that much more powerful.” Offering  its know-how drawn from years of experience in organic sourcing, Clif cheekily invited KIND to “raise the bar together.”

its know-how drawn from years of experience in organic sourcing, Clif cheekily invited KIND to “raise the bar together.”

Eco Virtues, Health Vices

Perhaps this was a truly heartfelt invitation, or maybe a marketing throw-down. Either way, the open letter raised eyebrows throughout the nutrition world, especially as it was issued during the Natural Products ExpoWest—a massive natural and organic trade show that drew nearly 90,000 people to Anaheim. Both companies exhibited at the show.

Whatever the motivation, the letter is the latest salvo in a bar fight that’s been going on for years.

As of this writing KIND has not taken Clif’s organic bait.

However, one week after Clif’s letter appeared, KIND—partially owned by Mars Candy—did petition the FDA to review federal policies and regulations for nutrient content claims on food labels, and to address widespread misleading claims.

FDA’s labeling regs were established in 1990. KIND contends that, “This regulatory framework is now significantly outdated as a result of scientific progress in the nutrition space, because it does not reflect key principles of today’s evidence-based dietary guidance.”

In his 13-page petition, KIND’s executive vice-president and general counsel, Justin Mervis, argues that existing regulations are “demonstrably not effective in actually helping consumers make appropriate dietary choices, but instead allows the use of nutrient content claims that mislead consumers to believe that the products bearing such claims provide useful evidence-based dietary value, when they do not.”

In early April, one month after the Clif Bar invitation, KIND launched a consumer-focused website called Sweeteners Uncovered, that compares hidden sugar content in various “healthy” snack bars, cereals, granolas and yogurts. Clif’s chocolate chip bar comes out at the top of that list, with 31% sugar (21 g per 68 g bar). KIND’s comparable bar has only 13% sugar (5g per 40 g bar).

Under a provocative line stating “How do your favorite “healthy” snack bars stack up to a serving of your favorite treats?” the site implies that Clif’s chocolate chip bar is basically junk food, equivalent to a Little Debbie Oatmeal Creme Pie containing 32% sugar.

If Clif is intent on goading KIND into going organic, KIND seems equally determined to point out that Clif’s eco-virtues don’t absolve its high-glycemic sins. “Organic” is not necessarily synonymous with “healthy.”

The high-stakes brawl may well be a case of two massive consumer products brands vying for market share. Or it could be that they’re each on to something important.

Beneath the hype and healthier-than-thou posturing, there’s evidence that conscious consumers — health care professionals among them — are hard-pressed to identify just what defines a “healthy” food. Less sugar? More transparency? Purer sourcing?

“There’s enormously misleading information, and anxiety among consumers,” says Devoured author Sophie Egan, who is the Culinary Institute of America’s Director of Health & Sustainability Leadership.

“There’s enormously misleading information, and anxiety among consumers,” says Devoured author Sophie Egan, who is the Culinary Institute of America’s Director of Health & Sustainability Leadership.

Driving Us Nuts

The FDA hasn’t rushed to provide answers. On the contrary, its policies can confound consumers and manufacturers alike, as KIND CEO Daniel Lubetzky knows first-hand.

KIND has positioned itself as having nothing to hide, with clear see-through packaging and whole non-GMO ingredients.

Even so, the company ran afoul of the FDA in 2015. The agency issued a warning that several varieties of KIND bars didn’t meet the definition of “healthy.”

The issue turned out to be nuts…coupled with the FDA’s outdated health standards.

Nut-dense products like KIND naturally contain fat—healthy, unsaturated fat. But at the time, the FDA didn’t distinguish between types of fat. The amount in the bars exceeded FDA standards, and the agency told KIND to remove the word “healthy” from its labels. Meanwhile, additive-laden fat-free products were allowed to continue waving the “healthy” banner.

The FDA reversed itself a year later, and the word “healthy” reappeared on KIND packaging, but the PR damage was done.

Lubetzky promptly began his campaign demanding the FDA provide greater clarity regarding nutrient claims. Three years later, nutrient claims still lack context.

Should We Abandon “Healthy”?

“The FDA’s general framework for nutrient content focuses on the quantity of nutrients in the food product rather than the quality of food in the overall diet,” says KIND spokeswoman, Stephanie Czaszar, RD.

“We agree there is room for improved regulation on nutrition labeling,” says Kelly Toups, Nutrition Director of Oldways, a nonprofit promoting the benefits of traditional food cultures. In 2017, Oldways filed its own petition to the FDA, recommending the abandonment of the term “healthy” entirely, “since overall diet determines health, not individual foods, and certainly not individual nutrients.”

Toups, and Oldways president Sara Baer-Sinnott, are among the 10 co-signatories of KIND’s new FDA petition.

Nutrition science is an ever-evolving calibration of individuals, food and wellness. For decades, the focus of the USDA Dietary Guidelines for Americans has been on specific nutrients and a “what’s-in-it-for-me” approach.

“Environment was not part of the “healthy” discussion,” says Egan. The 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee tried to change that, making sustainability a factor in dietary advice. They recommended encouraging more plant-based choices to improve individual and environmental health.

That move was ultimately shouted down by the meat and dairy industries. Encouraging Americans to reduce meat and dairy consumption didn’t sit well with them. However, the significant toll both industries exert on the environment doesn’t sit well with many health experts, environmental scientists, and watchdog agencies. Neither does the entanglement of special interest food lobbies with federal government agencies, an alliance that has resulted in what Egan diplomatically describes as “a lack of urgency in response to climate change.”

Plethora of “Plant-Based” Options

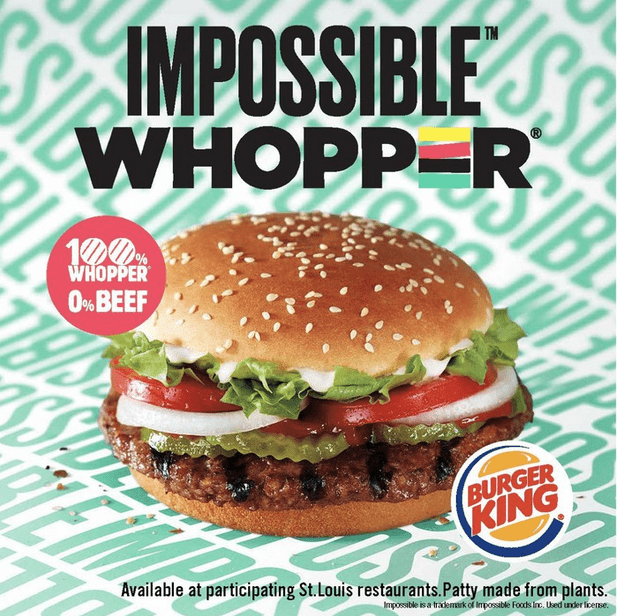

Food marketers have enthusiastically grabbed onto eco/sustainability messaging, hence the plethora of new “plant-based” products beckoning  consumers from supermarket shelves, and veg-centric restaurants vying for the nation’s dining dollars.

consumers from supermarket shelves, and veg-centric restaurants vying for the nation’s dining dollars.

When Burger King announced in April that it was testing Impossible Burger’s 100%-vegetarian patties in its signature Whopper sandwiches at 59 locations in the St. Louis area, it became very clear that the “plant-based” wave has hit mainstream shores.

As the impact of climate change, including severe weather, water shortages, compromised growing conditions, and global food insecurity grow more obvious with each passing year, Clif’s argument in favor of organic ingredients reflects the reality that sustainability is now open for discussion in corporate boardrooms worldwide.

Clif Head Nutritionist Casey Lewis says, “We firmly believe we are at a collective tipping point to make organic a mainstream option and we wanted to spark this conversation.”

Organic sales have been steady at an annual rate of 6.41% for years. Clif’s challenge to the industry could potentially drive that upward.

Since Clif’s letter to KIND, a dozen companies have pledged to convert to organics. Jenna Blumenfeld, Senior Food Editor of New Hope Network says, “Clif underscores how large brands in the natural food industry have immense power to change the landscape of our food system.”

Clif has also taken up KIND’s clean labeling charge.

What Means “Clean”?

“We are a strong advocate for transparency in labeling – we believe clear labels help consumers understand what’s in their food to make the right choices,” says Lewis, Clif’s staff dietitian.

But then, there’s that issue of the sugar. Organic sugar is still sugar, and in large quantities it is just as detrimental to health as sugar obtained from conventionally grown crops.

The definition of “clean” labeling is just as elusive as the term “healthy,” when it comes to product marketing.

Clif’s current packaging boasts that three-quarters of its ingredients are organic. But it doesn’t say which ingredients they are. Clif contains soy isolates, a highly processed form of soy, which is most likely from genetically modified soybeans, given that 98% of the soy in America does come from GM plants.

Sugar, linked to increased inflammation and risk of cardiovascular disease, appears in Clif bar ingredients in three different guises, and the brand has been sued for misrepresenting its disproportionately sugary products as “healthy.”

“Selling snacks made predominantly from brown rice syrup, which is a form of sugar, isn’t the solution,” says KIND’s Czaszar. Despite the fact KIND counts Mars Candy among its minority shareholders, Czaczar stresses that the brand doesn’t dress up candy with health claims.

“KIND’s priority is creating snacks made primarily from nuts, whole grains and fruits,” she says. “These nutrient-dense ingredients we know to be health-promoting and the foundation of a balanced diet.”

Clif’s Lewis responds, “To compare a snack bar to an energy bar is like comparing apples and oranges.” Clif, with a huge following among runners and other athletes, makes products designed to provide rapid energy delivery to sustain performance, while also tasting good (a claim not all energy bars and gels can make).

However, at the end of the day, KIND’s claim is correct — Clif contains more sugar than KIND.

Neither brand scores a perfect 10 in terms of environmental and personal health. Both contain nuts, which, while heart-healthy, makes them unsafe for people with nut allergies. Whether organically or conventionally farmed, nut cultivation entails significant water use. So, they’re not exactly environmentally neutral.

Neither brand scores a perfect 10 in terms of environmental and personal health. Both contain nuts, which, while heart-healthy, makes them unsafe for people with nut allergies. Whether organically or conventionally farmed, nut cultivation entails significant water use. So, they’re not exactly environmentally neutral.

Gold Bars

Regardless of whether they’re marketed for energy, protein, meal replacement or “healthy” snacking, bars are big business, with sales projected to reach $8.8 billion by 2023.

Americans are increasingly substituting them for meals. What’s in them matters. But it’s challenging for consumers—and medical practitioners– to determine what they contain.

“Look over the package. The front is mostly noise,” says Egan. “Other than product identity — energy bar, loaf of bread, can of tomato sauce — it’s a distraction, ignore it. Flip the product over. The two most important pieces of real estate are the nutrition facts panel and ingredients list. Look at both and cross-reference. That should give you a pretty complete picture of the nutritional merit of the product.”

Historically, the drivers behind consumer food choices came down to taste, convenience, price point, and health. In more recent decades, concepts like “natural,” and “sustainable” have also entered the equation.

The problem is, within the industry, “There’s not a solid definition for healthy or natural,” says Egan. “Standard definitions for both of those terms would be very helpful.”

They may be coming with the 2020 USDA Dietary Guidelines.

The new Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee is already at work. Practitioners, patients, and anyone wanting to be part of the healthy food conversation can submit comments.

“It could represent a pivotal moment in the definition of good food,” Egan says.

Of course, it’s important to keep in mind that if it has a label, it’s a processed food. And labels, even the best of them, only tell a part of the story–the part that the marketers want to tell.

As both Egan and Toups note, fresh fruits and vegetables — nutritious by anyone’s standards — don’t have labels at all. As the “bar wars” continue to rage, that’s a good point to keep in mind.

END