Mycobacterium Avium spp. Paratuberculosis. Scanning Electron Micrograph 3000X. Courtesy of Dennis Kunkel’s Science Photo Library.

If we are a little more thoughtful, some of us will tell our patients that the disease is “multifactorial,” with many contributing factors: age, ethnicity, family history, immunodeficiency, overuse of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, etc.

Neither explanation is satisfying for patients. Dealing with the symptoms of Crohn’s is hard enough. Not understanding why you are suffering just rubs salt in the wound. Too often, we tell patients they must just accept that they have a condition without a cause, a cure, or even a consistent symptom-management strategy.

But recent research is challenging these long-held beliefs. There is growing evidence that Crohn’s disease might have an infectious cause (McNees, A. et al. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015; 9(12): 1523–1534). One particular microbe is garnering attention: Mycobacterium avium subspecies Paratuberculosis, better known as MAP.

That’s good news, because a MAP infection may be treatable.

MAPping Crohn’s

MAP is a bacterium belonging to a family, Mycobacteriaceae, and the same genus as the pathogen that causes tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis).

MAP is also the cause of Johne’s disease, a systemic infection and chronic intestinal inflammation common in livestock. Johne’s disease sounds a bit like Crohn’s disease, doesn’t it?

The similarities go beyond the rhyme scheme. Both are forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD), and as such, they share several clinical and pathological features:

- Chronic diarrhea

- Dull hair

- Weight loss

- Cycle of remission and relapse

- Occasional granulomatous appearance

- Lesions in the esophagus and oral cavity; Ileum and colon; mesenteric lymph nodes, rectum, and anus.

In fact, these similarities are what led scientists years ago to suspect MAP might play an etiologic role in Crohn’s disease.

How Humans Acquire MAP

In ruminants like cows, MAP is transmitted primarily via the fecal-oral route. Most calves are infected within their first month of life. This early-life infection is followed by a long symptom-free period of 3 to 5 years.

Estimates are that between 68% to 91% of US dairy herds are infected with MAP, although most will not show any symptoms. Only 10% to 15% of infected calves develop fatal clinical disease (Arsenault, R. et al. Vet Res. 2014; 45(1): 54).

Beyond livestock, other animals––including rabbits and wild ruminants like deer––can also be infected with MAP.

The key point here is that cattle and other animals can shed the bacterium in their feces, even during the latency period. Once shed, MAP can live in soil or water for 12 weeks to 12 months.

And this spells trouble for humans.

MAP from livestock feces is deposited onto pastures, where rain can wash it into nearby water sources. In fact, MAP DNA was detected in over 80% of domestic water samples in the state of Ohio (Beumer, A. et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010; 76(21): 7367-7370).

And MAP is one tough bug––several studies show that it can survive chlorine disinfection treatment used in drinking water systems (Taylor, RH. et al. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000; 66(4): 1702-1705).

“There is growing evidence that Crohn’s disease might have an infectious cause. One particular microbe is garnering attention: Mycobacterium avium subspecies Paratuberculosis, better known as MAP. That’s good news, because a MAP infection may be treatable.” ––Jill Carnahan, MD

But it doesn’t stop there. MAP can also contaminate our food supply, especially dairy and meat products (Eltholth, M. et al. J Appl Microbiol. 2009; 107(4): 1061-1071). Pasteurization significantly reduces the risk, but does not eliminate it (Wynne, J. et al. PLoS One. 2011; 6(7): e22171). MAP has a very thick lipid-based cell wall that allows it to survive the pasteurization process (Lichtenstein, G. et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018; 113(4): 481-517).

In one study, up to 25% of pasteurized cow’s milk tested positive for live MAP during peak periods (Millar, D. et al. App Env Microbiol. 1996; 62(9): 3446–3452).

Bottom line: it’s pretty easy for humans to become infected with MAP.

The idea that MAP may play a role in Crohn’s disease is not new; it has been floating around at the edges of Crohn’s research for decades (Feller, M. et al. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007; 7(9): 607-613). But by and large, it has not been accepted by mainstream gastroenterology.

Given the widespread environmental prevalence of this microbe, it is fair to say that a large number of humans are chronically exposed. Yet only a small percentage of the population has Crohn’s.

How do we know there’s any connection between MAP and Crohn’s? If it is a factor, why does MAP exposure affect some people more than others? And why isn’t there an epidemic of MAP infection among dairy farmers?

MAP in Humans

A variety of factors influence a person’s susceptibility to developing Crohn’s associated with MAP. These include:

- Extent and frequency of exposure: People who experience frequent and constant exposure to high levels of MAP are more likely to develop Crohn’s or other gastrointestinal conditions.

- Route of infection: Routes of infection that increase the concentration of MAP, such as aerosolized water from contaminated rivers or hyperosmolar milk, increase the risk.

- Age: Children are more susceptible to the adverse impact of MAP than adults.

- Genetic and acquired susceptibility: Certain genes control how intracellular bacteria are processed. These genes have some effect on the risk of developing Crohn’s disease. Normally, macrophages eat and digest pathogens like MAP, and T-cells eradicate cells that contain the bug. When these processes do not occur for whatever reason, a person can develop symptoms.

- Prior health status: People with past histories of chronic illness may not be able to handle MAP exposures in the way that healthy people do.

- Gender: For reasons that are not clear, the odds of developing Crohn’s disease following MAP exposure are highest in infant males and adult females.

Two Forms of MAP

Paradoxically, children who come into contact with farm animals are less likely to develop juvenile Crohn’s disease than those not exposed to livestock (Radon, K. et al. Pediatrics. 2007; 120(2): 354-361). Part of the reason is that occupational exposure increases the antibody levels (Hermon-Taylor, J. Gut Pathog. 2009; 1: 15).

But there’s more to the answer––MAP exists in (and can switch between) two forms:

- ZN-positive phenotype: Mycobacteria are acid-fast organisms, meaning they have cell walls that make them resistant to acid-based decolorization used in common bacterial staining tests. These organisms need to be stained by a process called Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) staining, and are thus said to have an “encapsulated” or ZN-positive phenotype. This phenotype of MAP can live outside other cells when excreted by infected animals. However, humans are not susceptible to the ZN-positive form, and may even acquire natural immunity as a result of frequent exposure.

- ZN-negative phenotype: When MAP is taken up into a host’s white blood cells, MAP sheds its protective “capsule.” This “naked” form is known as the ZN-negative phenotype. ZN staining cannot be used to detect it. Even without its cell wall, MAP is tough and can resist many chemical and enzymatic efforts to destroy it. This ZN-negative form is also much more virulent to humans. It is the form found in most people with Crohn’s disease.

How to Test for MAP

Standard methods for detection of MAP, such as ELISA assays, have notoriously low sensitivity and specificity for this organism, which makes them unreliable. As discussed above, the ZN-negative phenotype found in most Crohn’s patients renders traditional bacteria staining tests useless (Jungersen, G. et al. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2012; 148(1-2): 48-54).

To add to these difficulties, ordinary microscopes can’t see MAP. Fecal cultures can identify its presence. But MAP grows very slowly––it can take 3 months or more just for colonies to appear on a culture dish.

Some studies have used molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to overcome these challenges. In clinical practice, however, the accessibility of these specialized tests is limited.

There is another way. Otakaro Pathways, a New Zealand-based company, has developed a reliable MAP biomarker test that is somewhat more accessible. It’s a blood test, so it does require a draw. Otakaro delivers results by e-mail in 30 days, so it’s definitely not quick. But it is the best option currently available.

Can MAP Be Treated?

The goal of conventional Crohn’s disease treatment is to reduce the inflammation that triggers symptoms, and to limit complications. A treatment plan typically involves:

- Anti-inflammatory drugs (ex: corticosteroids, oral 5-aminosalicylates)

- Immune system suppressors

- Antibiotics

- Pain relievers

- Iron supplements

- Anti-diarrheals

- Vitamin B-12, calcium, and/or vitamin D supplements

- Nutrition therapy

- Surgery

This is an imperfect approach, and relapses are common––even after surgery.

The conventional strategy does not take into account microbial pathogens like MAP. Not all Crohn’s patients carry active MAP infections. But for those who do, it will be nearly impossible to quell the inflammation without eliminating the bug.

MAP is a member of the M. avium complex (MAC), a group of atypical bacteria that is notoriously difficult to treat with standard antimicrobials. In a 5-year study of Crohn’s patients, treatment with anti-tuberculosis drugs (isoniazid, ethambutol, and rifampicin) gave no meaningful improvements (Thomas, G. et al. Gut. 1998; 42(4): 497-500).

There is, however, some evidence to suggest that MAP-specific treatments can result in at least a partial remission of Crohn’s disease. The state-of-the-art strategy against MAP includes a trio of antimicrobials that have shown impressive activity against mycobacterial species:

- Rifabutin (RIF)

- Clarithromycin (CLA)

- Clofazimine (CLO)

This combination has been put to the test in several trials, which have reported clinical remission rates from 44% to almost 90%. But it’s not a simple story.

Selby’s “Landmark” Study

The “landmark” study among anti-MAP trials was published by Selby et al. in 2007. This was a two-year, phase 3, parallel-group, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial designed to assess the combination therapy of a steroid and CLA, CLO, and RIF in 213 patients with active Crohn’s disease.

Although 66% of patients receiving the antibiotics were in remission within the first 16 weeks, there was no evidence of long-term benefit.

This was a big blow. For many clinicians, the failure to show long-term benefit signaled the demise of the MAP/Crohn’s hypothesis.

However, there are many weaknesses in Selby’s trial design and analysis.

For example, the investigators did not test patients to confirm MAP infection at baseline. That’s understandable given the aforementioned lack of easily accessible tests. But it makes it more difficult to draw clear conclusions.

Further, Selby’s group did not use optimal therapeutic doses for the three antibiotics tested. Had they included only patients with confirmed MAP infection, and given higher doses, the long-term outcomes may have been different.

In fact, when the results were re-analyzed using an intent-to-treat analysis, the three-drug combination did perform significantly better than the placebo. In contrast to Selby’s report that benefits peaked at 16 weeks and declined afterwards, the authors of the reanalysis argue that the benefits continued through week 104 (Behr, M. & Hanley, J. Lancet Inf Dis. 2008; 8(6): 344).

What does all of this mean? It simply means that the largest anti-MAP trial was unreliable and therefore, has limited relevance for clinical decision-making. It also revealed the need for a better-designed trial.

We didn’t get this study for a long time. That changed very recently.

RHB-104––A Groundbreaking Therapy?

Based on the slowly growing evidence supporting the MAP/Crohn’s connection, a company called RedHill Biopharma developed RHB-104––a novel fixed-dose formulation that combines CLA, CLO, and RIF in a single pill.

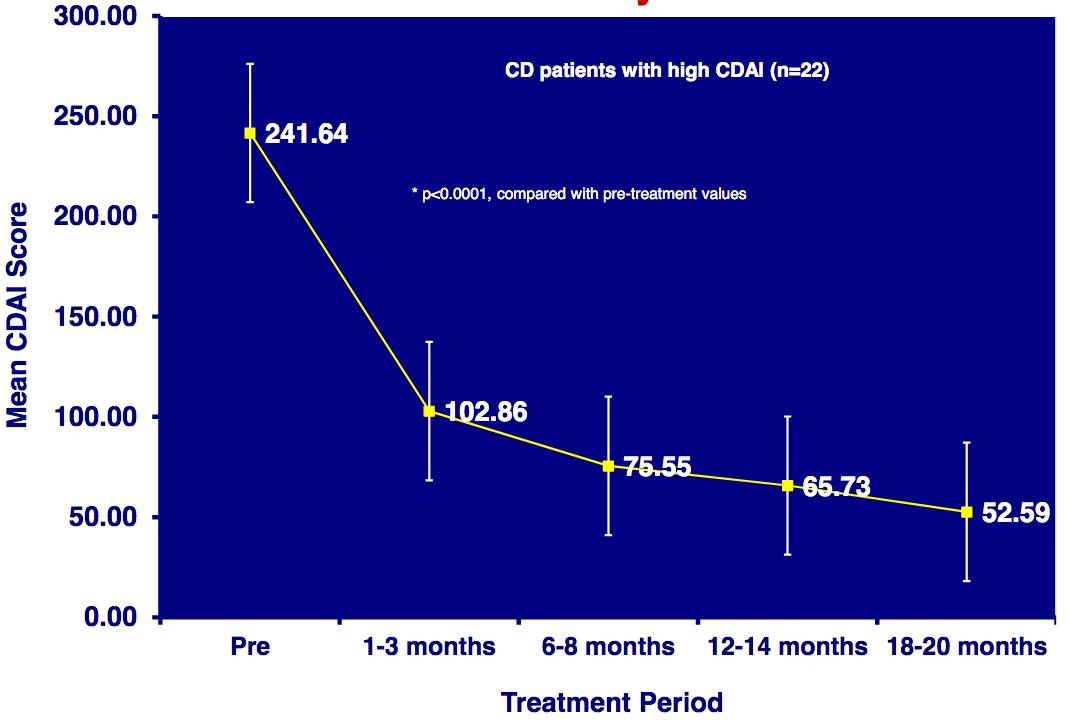

Improvement in Crohn’s disease scores over 20 months in patients receiving an experimental anti-mycobacterial compound (Borody TJ, et al. Digestive & Liver Disease. 2007)

Low-dose triple therapy makes the regimen more tolerable for patients, and decreases risk of bacterial resistance.

All of these findings influenced the development of RHB-104, which was put to the test in a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group phase III trial involving 331 patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s (Savarino, E. et al. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2019; 19(2): 79-88). Patients were divided into two groups:

- Those receiving five RHB-104 capsules orally twice daily (95 mg CLA, 45 mg RIF, and 10 mg CLO)

- Those receiving 5 placebo capsules orally twice daily

They took their assigned treatments for 26 weeks and were monitored for an additional 26 weeks. At weeks 16, 26, and 52, they were assessed for clinical remission, defined as a value less than 150 on the Crohn’s Disease Active Index (CDAI).

At each evaluation interval, RHB-104 demonstrated clear superiority over placebo. At the one-year mark, 25% of the active therapy recipients, but only 12% of the placebo recipients, were in clinical remission.

More information about this phase III MAP trial can be found at clinicaltrials.gov.

Real World Clinical Experience

I had the privilege of working with a young woman in her 20s, who’d been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn’s disease, and was having a hard time finding relief. On a scale from 1 to 10, her pain was about an 8 nearly every day. She was in agony all the time.

From my experience, I’ve learned to consider the possibility of infection whenever a patient is suffering from significant pain with no other obvious cause.

In this case, I did the typical Crohn’s workup: stool sample, blood tests to check for deficiencies and infection, etc. We also sent a blood sample to Otakaro Pathways, and results indicated that she indeed had a MAP infection.

With this information, I started her on two antibiotics. As mentioned previously, the norm for MAP is three, but my patient could not tolerate the third.

Within 60 days, she was pain-free and symptom-free. It was an incredible, dramatic turnaround! I had her continue taking the antibiotics for 9 months.

She did well for about 6 months, but then experienced a small relapse due to the high stress of wedding planning. We decided to put her back on short-term antibiotic therapy, and I am happy to report that she is doing very well.

Typically, I am not a fan of antibiotics. When used excessively and irresponsibly, they do irreversible damage to the gut microbiome. On a mass scale, they’re wreaking havoc by inducing resistance in many formerly treatable microbes.

But there are definitely cases like this, where a patient is suffering from a chronic illness that would otherwise have no cure, and where there’s reason to suspect a microbial pathogen. In such situations, antibiotics can be life-changing, sometimes even curative.

Of course, I carefully monitor my patients during long courses of antibiotics, and do everything I can to protect the gut, including:

- High-doses of probiotics (100–600 billion CFU/day)

- Strengthening the gut through natural supplements like Gut Immune

- Checking for signs of gastritis or pain

- Advising patients to take antibiotics with food

- Use of antifungals if signs of a fungal or yeast infection are present

Has the Crohn’s Mystery Been Solved?

Less than two decades ago, many Crohn’s experts argued that there were insufficient data to support the hypothesis that MAP could cause this disease. Some questioned whether it was even a significant human pathogen.

But the possibility that MAP causes human disease can no longer be ignored. Crohn’s has become a worldwide epidemic, and there is growing evidence that it is not an entirely autoimmune disease as previously thought.

We need better, more reliable, and more accessible methods of detecting, diagnosing, and treating MAP. That begins with acknowledging its potential role in the disease process.

END

Jill C. Carnahan, MD, ABFM, ABIHM, is the founder and director of Flatiron Functional Medicine, an integrative functional medicine practice in Louisville, CO. Dr. Carnahan is board certified in both Family Medicine and Integrative Holistic Medicine. She founded the Methodist Center for Integrative Medicine in 2009 and worked there as Integrative Medical Director until October 2010. She completed her residency at the University of Illinois Program in Family Medicine at Methodist Medical Center and received her medical degree from Loyola University Stritch School of Medicine in Chicago.