Stacy Ford was in her early forties when her doctor first noticed a lump in her left breast. She was worried, but thought that at her age it would be unusual to have breast cancer. But a suspicious mammogram and further testing confirmed a ductal carcinoma. She met with her oncology team (including her oncologist father) and quickly began treatment.

She had a lumpectomy and sentinel node biopsy. Thankfully the margins were good, and the node was negative. Next, she had radiation and remains on Tamoxifen three years later. All good news. Stacy is cancer free and moving forward.

But the effects of the cancer and its treatment linger on. For prevention of other potential cancers, she underwent an oophorectomy and hysterectomy. And she still has left-sided back and shoulder pain that her doctors attribute to the radiation. The estrogen-blocking drugs have caused early menopause. The Tamoxifen causes fatigue. And she has to undergo continued monitoring and surveillance.

The reality is that cancer survivors live in an ambiguous space between “well” and “ill.”

All this is time-consuming and stress-inducing: Stacy worries that the next mammogram will be the one that shows a recurrence. Her cancer physicians are terrific, but the longer she remains healthy, the less often she sees them. Her ongoing care is now managed mainly by her primary care doctor.

Ford is one of a growing number of patients who have lived through cancer and are now dealing with the long-term effects of treatment. Like many such patients, Stacy thinks her primary care doctor is great, but at this point mainly treats her as someone without cancer—as if things are back to baseline. The problem is, they’re not. As a cancer survivor, she has multiple complex and chronic conditions with which she must contend.

We primary care doctors need to be more aware of the long-term health challenges faced by cancer survivors.

Even ostensibly simple things like prescribing an SSRI can be impacted by a history of cancer. Ford says that her family doctor changed her anti-anxiety prescription recently. When she went back to see her oncologist, he told her that the new drug could interact with Tamoxifen and render it less effective.

A Growing Concern

According to the National Cancer Institute an estimated 1.8 million Americans were diagnosed with cancer in 2020. Overall, 39.5% of individuals will face a cancer diagnosis at some point in their lives. And even though there were over 600,000 deaths from cancer in 2020, treatment is improving and the number of survivors is growing rapidly. There are currently 16.9 million cancer survivors in the US and that number is projected to reach 22.2 million by 2030.

As primary care physicians, we routinely encourage cancer screening for our patients. We are highly competent at detecting even subtle abnormalities in physical exams or lab results that might indicate early-stage cancer. We make sure our patients get follow up mammograms when there’s something suspicious, and we dutifully follow things like lung nodules with serial CT scans.

When something does turn up, we are usually the ones who communicate the difficult news to our patients, and we make the proper referrals. But all-too-often our involvement in cancer care ends there.

During cancer treatment we typically see our patients much less often. This is understandable given the rigorous surgeries and treatment protocols they undergo.

But when these patients do come back to us as survivors, we usually revert to treating them like we did before. Sure, we add cancer to their histories and their list of previous diagnoses, and we help them arrange and manage follow-up testing.

But we seldom consider the long-term impact of cancer and its treatment.

Mindset Shift

Dr. John Librett is working on shifting medicine’s mindset toward cancer survivors. Librett, who holds a PhD in public health, has a very personal stake in this issue. He was diagnosed with thyroid cancer in his twenties. Using the skills he honed in his training he was able to research his condition in depth, and he found ways to augment the treatment he got from his oncology team without circumventing them.

Throughout this process he encountered patients with similar concerns. They were getting good oncologic care but weren’t able to take advantage of the myriad nutritional and non-pharma treatment options that could enhance their outcomes. He realized he was in a unique position to promote these synergies.

“Ideally, a focus on survivorship care should start the moment a patient receives a cancer diagnosis.”

–John Librett, PhD

The fields of holistic medicine and conventional allopathic medicine had somehow been at odds with each other for decades, especially in the realm of cancer care. Dr. Librett saw an opportunity to bridge the two, so patients could avail themselves of both, to the detriment of neither.

After completing his initial treatment, Librett became the executive chairman of Survivor Wellness, a Utah-based non-profit educational resource to help cancer patients navigate the increasingly complicated world of integrative treatments for cancer. Today, the organization has extended its educational efforts to include a strong focus on long-term cancer survivors.

“I had the best doctors out there,” he says, “but they just didn’t have the bandwidth to look into all other promising treatments.” So Librett did his own research.

He quickly came to realize though that though his cancer was “cured” there would likely be lingering issues that would need ongoing attention throughout his life. For example, the radiation therapy he underwent to shrink the thyroid tumor also caused premature carotid and coronary calcification. He is also at risk for premature osteoporosis.

Like the treatment of cancer itself, Librett found that these comorbidities and sequelae were best addressed holistically.

Between “Well” and “Ill”

The reality is that cancer survivors live in an ambiguous space between “well” and “ill.”

In addition to the side effects of the initial treatments, many must continue on highly potent drugs for months to years. They are under continuous surveillance with repeat scans, blood tests, and scopes—all of which carry the dread that the next test will reveal a recurrence.

Cancer survivors between the ages of 18-39 had higher rates of angina, arthritis, COPD, heart attack, and stroke compared with their peers. Survivors aged 40-64 had all of the above, along with a higher prevalence of pain, fatigue, and sadness.

Librett and colleagues gathered comprehensive resources to help survivors and their families to face these challenges together. He offers free counselling and other supportive services, along with an actual physical space just to gather.

He feels there is a need for much broader recognition, support, and treatment for cancer survivors and their caregivers.

Better treatments and higher survival rates are turning cancer from a terminal illness to a chronic disease. Today, many people live for decades after cancer. While some malignancies are never completely eradicated, many have been rendered controllable.

From Terminal to Chronic

But the price for that success is that the effects of cancer treatment—whether or not it is ongoing—have lasting health impacts.

A 2017 cross-sectional study by Pfizer researchers outlined some of the problems cancer survivors face.

Using information from publicly available databases such as the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results database, and National Health Interview Survey and Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the authors identified the eleven most common cancer diagnoses in people 18 years of age and older. These were: hematologic, melanoma, lung, breast, prostate, colorectal, bladder, renal, uterine, thyroid and pancreatic malignancies.

Breast cancer had the highest incidence among females, and prostate was highest amongst males.

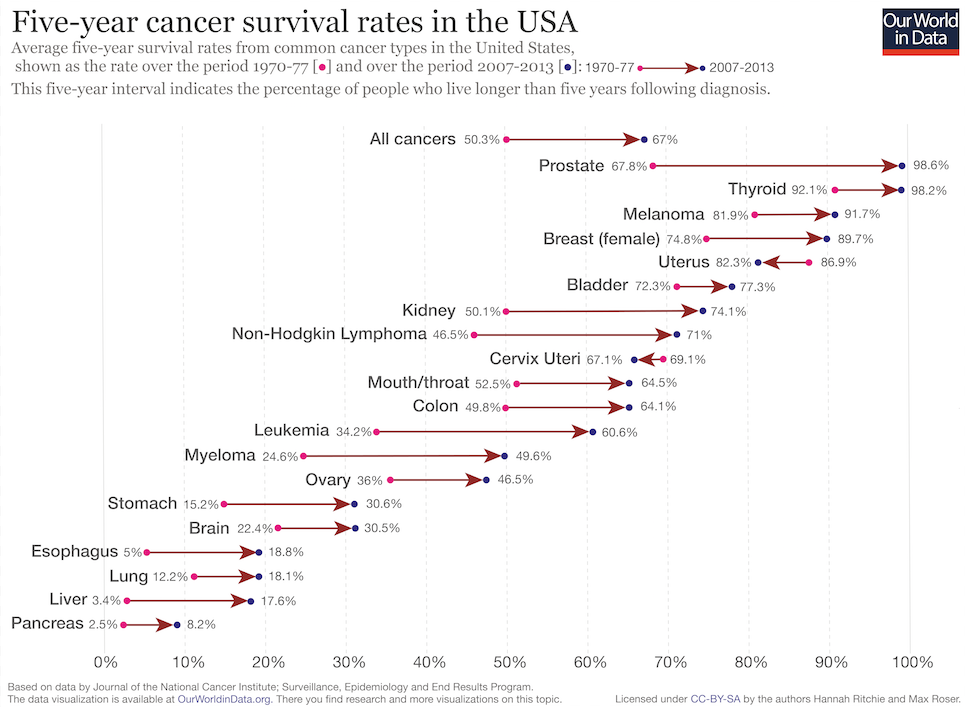

A lot of these cancers have high survival rates; many have a greater than 50% survival rate regardless of stage at diagnosis. Survival is highest for thyroid, prostate, melanoma and breast cancers.

But these cancer survivors have higher rates of comorbidities compared to control cohorts of similar age and socioeconomic background.

For example, survivors between the ages of 18-39 had higher rates of angina, arthritis, COPD, heart attack, and stroke compared with their peers. Survivors aged 40-64 had all of the above, along with a higher prevalence of pain, fatigue, and sadness. Patients 65 and older also reported more limitations in function than non-cancer controls.

Like the premature arterial disease that Librett has experienced, many comorbidities link even more directly to treatment. The commonly deployed chemotherapeutic agent Taxol for example, can cause peripheral neuropathy.

All of this speaks to the ongoing echoes of cancer in the lives of those who have had it.

Survivor Care

We as holistically-minded primary care physicians—with our whole person, big picture mindsets–are perfectly positioned to address the comorbidities associated with cancer survivorship.

Librett says that ideally, a focus on survivorship care should start the moment a patient receives a cancer diagnosis.

“At that moment,” he says, “right now, let’s check all of the potential downstream effects of treatment so that we can plan for future health.”

From the outset, primary care doctors can help patients optimize health and wellness going into cancer treatment. We can help develop a reasonable physical activity program and identify what foods might be most (and least) supportive.

Are there ways to optimize the microbiota? What strategies or referrals can we make for mental health and wellbeing? Might acupuncture help with treatment side effects?

Beyond the practical value of these strategies, Librett feels that even just having these discussions bolsters resiliency going into treatment.

And once someone has been through treatment, the same considerations apply.

Look at Taxol, for example. It is commonly used to treat breast and ovarian cancers. Librett says most patients he counsels experience peripheral neuropathy as a side effect of this drug.

“Wouldn’t it be great if, going into treatment, we were mindful of this, and could strategize ways to mitigate it? And then if patients do have side-effects like this, we support their unique survivorship issues going forward.”

Librett recognizes that survivorship care initially seems intimidating. The broad scope of primary care trains us to see the big picture, but sometimes leaves us worrying that we are not adequate in terms of the finer details and nuances of oncology care.

While acknowledging these fears, he says that it is usually sufficient to understand the most common cancers and cancer treatments at a basic level. You don’t need post-doctoral oncology training to do this sort of work. “It’s less complicated than you think,” he says.

For her part, Stacy Ford wishes that she’d had conversations with her primary care doctor to map out ways to optimize both her cancer treatment and ongoing post-cancer health. She says that she was so focused initially on the scary diagnosis that she really didn’t give a second thought to what life would be like after treatment.

“I just didn’t have the bandwidth,” she says. “You hear the word ‘cancer’ and you really just can’t think about much more that the immediate.” She says it would have been so helpful if her family doctor had the long-term considerations in mind.

With the number of patients in Ford’s situation rising, practitioners who are aware of the comorbidities and long-term effects of a cancer diagnosis and treatment will be in high demand. And those with a holistic mindset will be particularly sought after.

Librett feels that insurance companies and Medicare will also be increasingly willing to reimburse specifically for cancer survivor care. But it will require advocacy and a mindset shift. “It’s not cancer care, it’s not primary care, it’s survivor care.”

END

Grant Jackson, MD, is an integrative family physician and journalist in Salt Lake City, UT, where he directs his own private practice, Jackson Integrative Health. He earned his MD defree in 2005 from the University of Utah, and did his residency training at Washington Hospital. He completed the University of Arizona’s Integrative Medicine Fellowship in 2016. He enjoys fly fishing, skiing, reading, cooking, and time with his wife Julie and their 4 children.