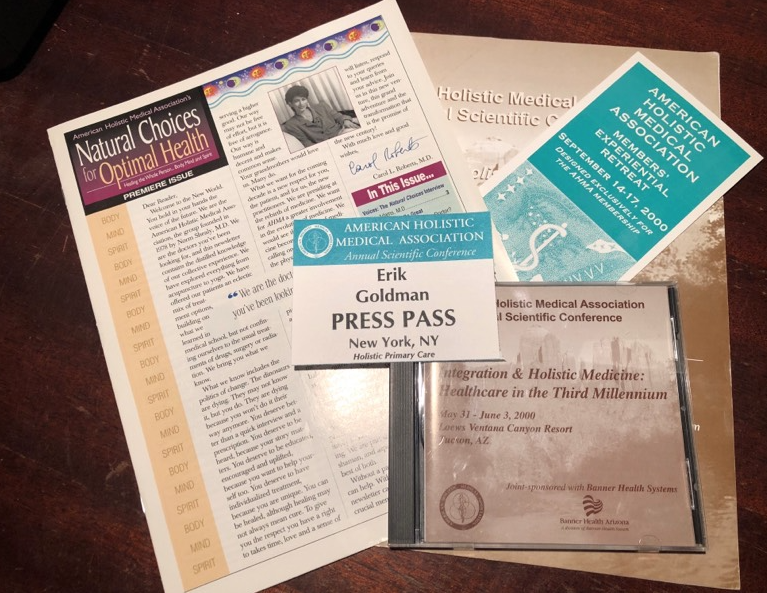

On October 15, 2000, the first edition of Holistic Primary Care rolled off the presses at Democrat Printing & Lithography in Little Rock, Arkansas, and into 60,000 doctors’ offices across the country.

And just like that, an idea had back in 1986 had suddenly become a tangible reality, giving voice to a movement aimed at transforming American healthcare.

The saga of Holstic Primary Care began when I was a novice medical writer, fresh out of college, and covering various medical specialties for pharma-sponsored news publications.

My job had me attending a lot of CME conferences, and I quickly noticed that all these meetings were focused on drugs, high-tech tests, and invasive surgeries. There was nothing on nutrition or prevention beyond lip service about “diet and lifestyle change,” and rote messages on sunscreens, mammograms, and digital rectal exams. In short, there was very little about “health” at these conferences.

Yet we already knew, way back then, that lifestyle and environmental factors were the key drivers of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, irritable bowel, and other chronic conditions.

At the time, I was exploring vegetarian living, and reading a lot about vitamins and herbs. I was fascinated by things like acupuncture, hypnosis, Ayurveda, and Tibetan medicine. So were a lot of my friends.

“Someone ought to do a publication for doctors about holistic medicine,” I thought, as I sat through yet another tedious session on pharma fixes for lifestyle diseases.

Wake Up Calls

Fast forward to the 1990s. Times they were a’changin’. At least they seemed to be.

In January 1992, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter entitled “Physicians and Healers—Unwitting Partners in Healthcare.” In it, Raymond H. Murray and Arthur J. Rubel, urged physicians to wake up to the fact that millions of Americans were seeking out “alternative medicine.”

With the alarmed tone of parents who find weed in their child’s dresser, Murray and Rubel wrote, “Most physicians are unaware of its popularity, much less that many of their own patients are also being cared for by practitioners of alternative medicine.” They also note that, “there are good reasons to believe that alternative medicine has many adherents among all social classes.”

That’s code for, “Even your friends might be doing it.”

Then came a wave of papers by Harvard’s David Eisenberg and colleagues, documenting the widespread popularity of “CAM” (complementary and alternative medicine) as they called it.

In 1993, Eisenberg’s group estimated that one-third of US adults were using some form of “alternative” medicine and usually not telling their physicians. In their 1998 follow-up, “CAM” use had increased to 42%, amounting to roughly 629 million office visits per year, a number that exceeded total visits to mainstream primary care.

A Movement Emerges

The big brow-raiser was the fact that Americans spent roughly $21 billion annually on care outside the mainstream.

“Someone ought to do a publication for doctors about holistic medicine,” I thought, as I sat through yet another tedious session on pharma fixes for lifestyle diseases.

Eisenberg and colleagues not only studied this trend, they fueled it. Harvard was arguably the first mainstream institution to host CME conferences on medical alternatives. They continue to innovate, most recently with their Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives courses that teach healthy cooking skills to medical professionals.

By the mid 90s, pharma companies were launching supplement brands. Leading medical centers were starting “integrative” clinics. Congress passed the Dietary Supplements Health and Education Act (DSHEA), laying the regulatory framework for the newly minted “supplements” industry.

Congress gave a green light to establish the National Center for Complementary & Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) within the National Institutes of Health.

Suddenly it was OK for MDs to talk about fish oil, probiotics, and acupuncture. Marginalized modalities like Naturopathy, Chiropractic, and Ayurveda began to take their places.

These were not disparate and unconnected events; this was a movement.

A Simple Vision

That old idea kept a’ knocking, and this time it was insistent: “Someone ought to….”

I never for a moment thought that the “someone” was me. I was a writer, after all. What did I know about starting a business?

Enter Meg Sinclair, HPC’s chief instigator, without whom none of this would have happened. She took on the role of publisher, and provided the practical executive skills and financial support needed to translate the HPC vision into reality.

“Let’s do it!” Meg said. And so Holistic Primary Care was born in the Fall of 2000, in a loft in New York City’s East Village.

The vision was simple: Provide doctors with information to put the “health” back in healthcare, and build bridges between the diverse world of “alternative” modalities and the medical mainstream.

The Name Game

We chose our name very deliberately.

At the time we launched, “CAM” was the official term, and several people advised us to embrace it…something along the lines of “CAM News.”

We politely declined.

“Complementary” made it sound like this medicine was free, or worse, that it was merely a little green garnish on the pharmaceutical main course.

“Alternative” invoked the adversarial dynamics we were trying to transcend. Plus, the word “CAM” made me think of auto parts.

Then, there was that catch-all term “integrative,” a convenient way for the allopathic mainstream to define anything and everything it had previously excluded.

We felt that the real “integration” that we needed would be the integration of allopathic medicine within the broader spectrum of all healing modalities. But the “Integrative medicine” model of the late 1990s, seemed to be about cramming all these other modalities into allopathy’s narrow toolbox—and its financial constraints. This struck us as misguided.

“Holistic,” deriving from the Greek “Holos,” was descriptive of a way of seeing that underlies many different–some would say divergent–systems of practice. And it seemed ideally suited to the content we wanted to provide.

Mentality, Not Modality

Holistic medicine is not a specific treatment or clinical tool. It is a way of thinking, rooted in the fundamental concepts of relationality and synergy. It recognizes that organ systems are related to one another; that biochemical pathways are interconnected; that we human beings are in relationship with one another and with our environments. Nothing is separate or isolated, even if sometimes it seems to be so.

Functional medicine pioneer Jeff Bland—a constant source of inspiration and encouragement for us—once put it this way: Dividing the body by organ systems is a convenient way to organize a medical school, but it is not reflective of biological reality.

“Holistic medicine is not a specific treatment or clinical tool. It is a way of thinking, rooted in the fundamental concepts of relationality and synergy. It recognizes that organ systems are related to one another; that biochemical pathways are interconnected; that we human beings are in relationship with one another and with our environments. Nothing is separate or isolated, even if sometimes it seems to be so.”

Inter-relationships between systems can be reciprocal and well-balanced, engendering health. Or they can be dysfunctional and out of balance, engendering illness. But they are relationships none the less. A holistic approach recognizes this. And the logic of holistic thinking can guide any particular medical treatment.

As our old friend and advisor Dr. Lev Linkner explained, one can do surgery holistically, and one can use herbs or supplements allopathically.

It’s the mindset, not the toolset, that really matters.

Growth and Evolution

Much has changed since October 2000, when HPC made its debut.

Concepts considered “fringe” back then—probiotics, leaky gut, systemic inflammation, gluten sensitivity, personal genomics—have made their way into mainstream practice. The role of nutrition in preventing and reversing disease—once dismissed as “irrelevant”—is now promoted by leading medical organizations.

Most major medical centers have some sort of integrative or functional medicine clinic. Some—like Cleveland Clinic, Mayo Clinic, and University of California Irvine, have made significant clinical and research investments in the field.

The Bravewell Collaborative—a philanthropic endeavor that emerged in 2001—funded the establishment of the Consortium of Academic Health Centers in Integrative Medicine (CAHCIM), created research centers at 10 major medical schools, provided fellowship grants for roughly 100 young holistic physicians, brought about a summit non integrative medicine within the Institute of Medicine, and nurtured the development of this field in many other ways.

The supplement industry—a sapling offshoot of the health food movement when we started HPC—is now a $122 billion piece of the American economy, according to a recent analysis by the Council for Responsible Nutrition.

According to our own practitioner surveys, most physicians–even those who identify as “conventional/allopathic”—regularly recommend some supplements to patients. Over 80% of HPC readers routinely discuss nutrition, and in 2019, 65% said they were dispensing supplements in their practices—up from just 34% in 2013.

The naturopathic profession has evolved remarkably over the last 2 decades, with NDs and NMDs now licensed or license-eligible in 25 states and jurisdictions. It was only a handful when HPC first launched.

We’ve also seen the evolution of nutrition counseling, health and wellness coaching, and fitness training as vibrant and vital professions, and the emergence of nurse practitioners as independent, full-scope primary care clinicians. Many nurses, coaches and nutrition professionals are seeking advanced training in holistic and functional medicine. These are all very positive steps.

Even the staunchly conservative field of dietetics has leaned in a more holistic direction over the last decade.

Looking Beyond the Letters

The truth is, no one medical discipline, no one modality, no one degree has all the answers. Today’s clinicians seem much more willing than their predecessors to recognize that, to look beyond their degrees, and to learn from those with different skill sets.

One shining example of this is Dale Bredesen, MD, a conventionally trained neurologist and researcher specializing in Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline.

After decades of pharma research dead ends, Bredesen became convinced that mainstream medicine’s model of dementia was fundamentally flawed. Alzheimer’s is not a simple disease with a single cause, fixable with a silver bullet drug. It was the net result of complex nutritional, environmental, and behavioral factors.

Today, Bredesen’s protocols—which depend on thorough lifestyle assessment, dietary change, and personalized supplementation protocols, are not only preventing Alzheimer’s, they are reversing it.

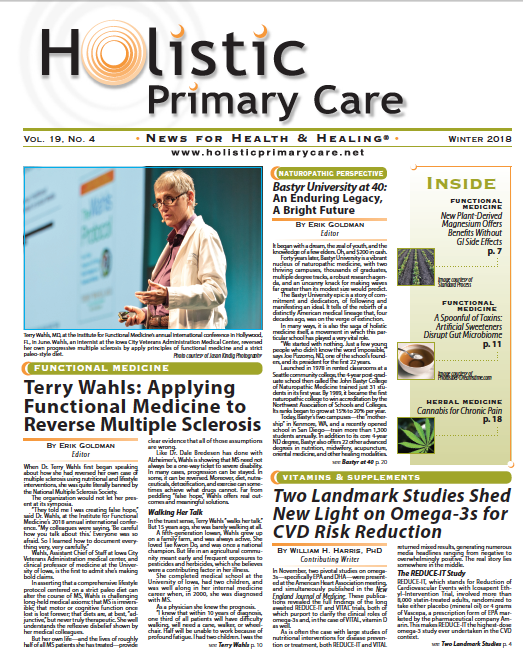

Similarly, Dr. Terry Wahls—an internist who biohacked her own multiple sclerosis through lifestyle change and supplementation—is now teaching thousands of other MS patients how to do the same. Wahls is finally earnings respect from the medical mainstream, after suffering years of nay-saying. The University of Iowa, where she is based, is supporting her research, and the MS Society—which once warned her against “spreading false hope”–gave a $1.5 million grant to her research institute.

The Department of Defense, particularly the Veterans Administration, has been very receptive to holistic medicine. Under the guidance of Dr. Tracy Gaudet—an early graduate of Dr. Andrew Weil’s University of Arizona integrative medicine fellowship—the VA has instituted system-wide programs for holistic non-pharma approaches to pain and PTSD management.

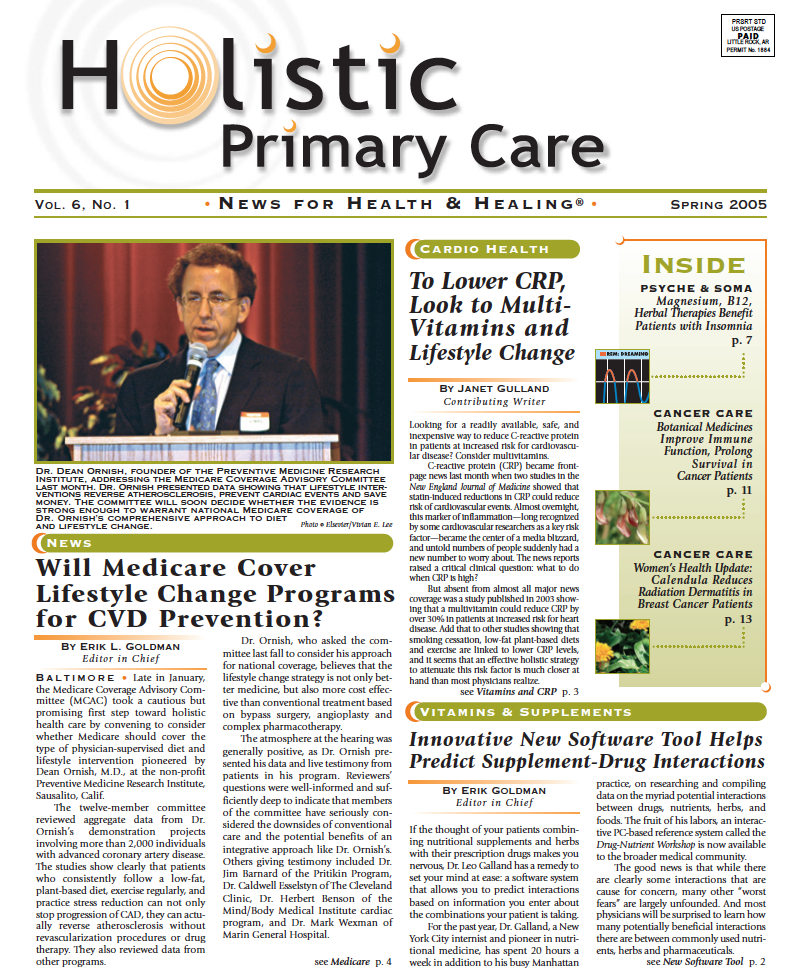

As the fields of holistic, functional, and naturopathic medicine have evolved, HPC has been here to chronicle all these changes, to give voice to new and emerging ideas, and to spotlight the values, virtues, and victories that shape the field. We’re proud that our stories have often been way ahead of the curve.

Since our launch, our original print publication has spawned our flagship website, the Holistic Education Exchange, our monthly UPshots e-newsletter, and an ongoing series of webinars, and white papers. The seminal Heal Thy Practice conferences we ran from 2009 through 2015 transformed the practices of hundreds of physicians.

Our annual Quality Counts reports provide clinicians with guidance on the regulatory and quality assurance aspects of the supplement and nutrition industries. And our yearly Practitioner Channel Forum is helping the nutrition industry to better serve the clinical community.

Stuck at a Tipping Point

Yet, for all the positive change, much remains frustratingly the same as it was 20 years ago. Our field seems to be perpetually stuck at a tipping point.

The ways in which we finance healthcare in this country are obstacles to the further growth. Big insurers still shut out most holistic modalities. Sure, there have been small victories, like Medicare’s historic 2005 decision to cover the Dean Ornish lifestyle programs for preventing and reversing heart disease.

But for the most part, access remains limited to those who can pay out-of-pocket, which means millions of people are excluded.

Many institutions still treat holistic and functional medicine like a novelty or a marketing ploy. The economic framework of insurance-based medicine still incentivizes prescriptions and procedures, not prevention and comprehensive healing. The ICD-10 code book—and the way of thinking it entrains—still dominates too many aspects of practice.

Despite all the marketing tropes about “patient centered care,” and “wellness,” insurers incentivize fragmented rather than coherent care.

As a result, many holistic and functional medicine practitioners struggle to stay afloat financially, and ordinary people are unable to afford the care they want and need.

We are aware that insurance-free models can support holistic practice, and equally aware of the potential dangers inherent in the very idea of insurance-based holistic care. But the truth is, the costs put concierge/membership practices out of reach for a majority of Americans.

We are frustrated by the loss of several of the field’s pioneering institutions. The University of Arizona’s Center for Integrative Medicine and Beth Israel’s Continuum Center are but two examples of popular and innovative clinics forced to close owing to lack of support from parent hospital systems, failure to develop sustainable fiscal models, or both. University of Bridgeport’s naturopathic school—the East Coast’s only naturopathic training program—is the most recent casualty.

While millions of Americans struggle to pay for their healthcare—and some resort to crowd-funding—the CEOs of major insurance plans, continue to pay themselves tens of millions each year. Meanwhile, bureaucratic nonsense—both from the federal and from the private sector payors–continues to make life miserable for too many well-intentioned practitioners.

As we reported in a 2017 article entitled Doctors vs Insurance CEOs: A Tale of Two Surveys, the top insurance executives are paid nearly 40 times what the best-paid physicians (orthopedic surgeons and interventional cardiologists) make. Primary care is at the low end of the pay scale; nurses, naturopaths, and nutritionists earn even less.

Meanwhile, our elected officials continue to play political football with the issue of whether or not health insurance is a right, a privilege, or a burden, while largely ignoring the factors that stoke illness and the interventions that would improve health status.

And all too often, we’re still looking at issues of health and illness through the lenses of war.

Back in 2003, Dr. Gladys McGarey—one of our greatest and most enduring inspirations—said, “The fun of medicine was lost when medicine became a war machine.” She pointed out how military language is so deeply engrained in medical thinking, and how war has been the dominant medical metaphor for decades.

Dr. McGarey, who turns 100 this November, is calling forth a new medical paradigm based in a metaphor of nurturance rather than violence.

We couldn’t agree more.

The COVID Mirror

COVID-19 has had a profound and unprecedented impact on healthcare. It underscores all the shortcomings of our current disease-based system and amplifies the need for comprehensive holistic health support. COVID is a mirror that reflects back to us all that is amiss in our medical systems and in our society at large.

Mainstream medicine still has no drug, no vaccine, and no procedure to treat or prevent COVID.

Consequently, many more people now recognize that self-care is not a luxury; it is a necessity. They know chronic conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and obesity raise the risk. They also know holistic, naturopathic, and functional medicine can provide solutions.

Yet we are still having to justify even talking about nutrients and herbs as tools

for improving resilience, strengthening the immune system, and mitigating the

risk burden of chronic diseases.

COVID has radically altered the healthcare landscape:

- Many clinics remain partially or fully closed.

- Online telemedicine consultations are soaring.

- Online meetings, webinars, and Zoom calls have replaced conferences and tradeshows as our main modes for connecting with each other, creating community, and reinforcing our values

- Regulatory scrutiny of our field is on the rise.

As you and your patients navigate this new and uncharted landscape, know that HPC is right here with you.

- We will continue to provide you with engaging holistic content, while offering you a spectrum of effective multimedia advertising and marketing opportunities.

- We will continue to survey the clinical community, and provide data on how this field is faring.

- We will continue to be an independent, interdisciplinary voice for natural medicine in today’s clinical world.

Over our 20 years, HPC has endured the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center—just 7 blocks from our old headquarters. We weathered the financial meltdown of 2008. We sailed the changing tides of healthcare reform.

Through it all, we’ve held close to original vision of helping practitioners put the “health” back in healthcare.

One of the great rewards of this work has been the opportunity to meet, interview, and often become friends with brilliant, innovative physicians and researchers—people who have cleared the path and lit the way toward a more humane approach to medical care.

Meg and I are grateful for the continued inspiration and encouragement we receive from so many of you. We are also grateful to all of you who’ve contributed articles, feedback, and survey responses over the years.

We are especially grateful for the many companies who’ve supported HPC with advertising and sponsorship. None of this would be possible without them.

As we step into our 3rd decade, we renew our commitment to providing you and your colleagues with engaging, inspiring, scientifically-sound content.

We hope you’ll join us in this new phase of our journey.

END