For decades, the United States has failed to invest in primary care. The result is a situation that has sorely compromised the health and well-being of patients and practitioners alike.

Though it consistently accounts for 50% of all annual medical visits, primary care represents less than 7% of the nation’s total healthcare expenditures, and receives 0.2% of all National Institutes of Health funds, according to the Larry A. Green Center, a primary care advocacy organization.

Long before COVID, many primary care doctors experienced financial and personal distress trying to meet the conflicting demands imposed by the healthcare systems. The pandemic, which forced some clinics to close and left others struggling to implement complex new precautionary measures—exacerbated an already precarious situation.

Primary care is “under-funded and over-demanded,” says Wayne Jonas, MD, Executive Director of the Samueli Integrative Health Programs. “To actually implement the current requirements for good health maintenance would take 20 hours a day with a full patient load. That’s an untenable situation. It leads to—especially among conscientious providers—a moral injury. They’re expected to do things they simply cannot do.”

Jonas says depression, anxiety, financial distress, substance abuse, and suicidality are rampant in medicine, especially in primary care. The situation has gotten worse since COVID (See Dοctor Suicide & COVID: Two Epidemics Converge).

Overload & Uncertainty

Data from the Green Center’s ongoing survey of roughly 450 practitioners bear out Jonas’ contention. The July 27 report indicates:

- 63% of respondents say stress is at an all-time high; 48% say burnout is at an all-time high.

- 45% say the pandemic has harmed their psychological well-being; 36% say it has affected their physical health; 33% say it adversely impacted their families.

- 26% are working in physically and emotionally damaging environments, facing unrelenting pressure.

- 60% lack sufficient Personal Protective Equipment, and 20% have had to purchase their own PPE at extremely high prices.

- 19% say their clinics are critically understaffed.

- 44% report face-to-face patient volume is 30-50% lower than pre-pandemic levels, threatening the fiscal viability of their practices.

- 19% report financial losses, owing to limits on the number of daily visits due to physical distancing requirements and reduced staff.

- 20% are uncertain about the financial viability of their practices beyond the next 4 weeks; 20% have skipped or deferred their own salaries at some point.

Dr. Jonas, who is also a retired Lieutenant Colonel in the US Army Medical Corps has learned a thing or two about moral injury, burnout, PTSD, and resilience over his long career in both military and civilian healthcare. He’s studied these phenomena across diverse settings, and developed self-help tools to address them.

Primary care is “under-funded and over-demanded. To actually implement the current requirements for good health maintenance would take 20 hours a day with a full patient load. That’s an untenable situation. It leads to—especially among conscientious providers—a moral injury. They’re expected to do things they simply cannot do.”

Wayne Jonas, MD

Resilience, is more than simply “bouncing back the way you were,” he explained in a recent interview. “It means coming back, growing, and thriving, and learning from a trauma.” And make no mistake, practicing medicine in the COVID context is traumatic.

Because of his extensive experience with stress and PTSD in the military, Jonas was called in by several New York City hospitals during last Spring’s COVID peak, to help front-line clinicians manage the overwhelming stress and cultivate resilience.

Modelling Vulnerability

The first step, he says, is to acknowledge the realities of over-stress and burnout. That needs to come from the top—from the nation’s healthcare leaders.

“Leaders need to model vulnerability,” Jonas says. “They need to demonstrate that providers are vulnerable and that in this environment they’re getting injured. This is the most effective way we dealt with PTSD in the military—when the top and most respected generals came out and talked about their own PTSD, depression, anxiety, nightmares, alienation, anger, and then what they did to get themselves back on track.”

“You can’t be a good healer unless you yourself are in a good place. Self-care is essential in healthcare. We need to provide resources so doctors and other medical professionals can do this without any kind of label or stigma. “

Wayne Jonas, MD

Within medicine, as in the military, people are afraid they will be stigmatized if they openly admit they are distressed and unable to cope. They fear they’ll lose hard-won positions. So, they bury and hide the problems, until they reach a breaking point.

When top leaders publicly admit their own struggles, they give permission for others to do the same—hopefully before they harm themselves, their patients, and their families.

Signs of Progress

Jonas says he’s seeing signs of progress. The American Academy of Family Physicians has been especially proactive. Several years ago, AAFP made “physician wellness” the theme of its annual conference, developed a series of online “Physician Health First” learning modules, and urged members to pay close attention to their own well-being.

AAFPs efforts dovetail with the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Wellbeing and Resilience, launched in 2017.

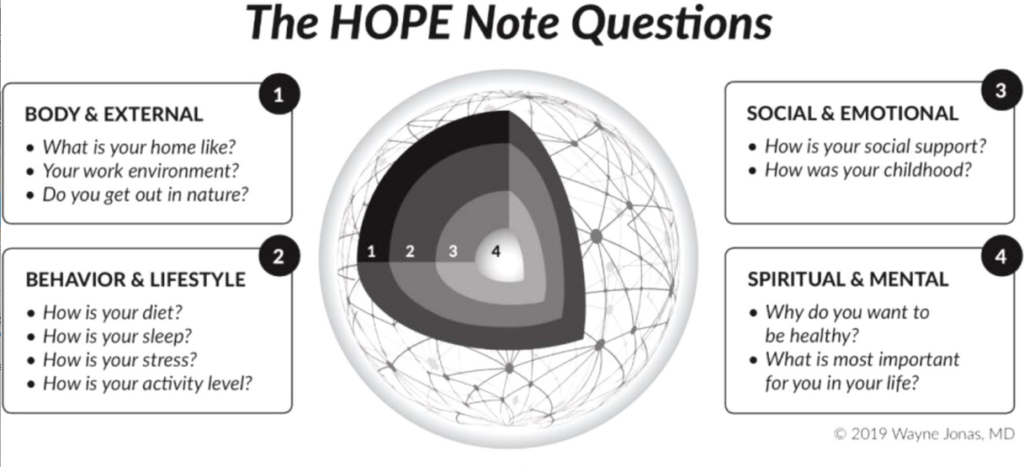

Dr. Jonas himself has been working on a set of self-assessment and self-help tools to help doctors recognize and mitigate their own stress and trauma. They’re based on his HOPE Note program for implementing holistic medicine into patient care.

From SOAP to HOPE

A riff on the ubiquitous SOAP Note evaluation framework, the HOPE (Healing Oriented Practies & Environments) Note tool provides a systematic way to quickly assess underlying determinants of disease from a whole-person perspective.

In a simple way, it aids clinicians in determining:

- What matters, not just “What’s the matter”?

- What is your goal for healing? What’s meaningful to you?

- What makes you feel well and healthy?

- What are you already doing to support your health & healing?

- What is your level of social support?

- Experiences with past traumas and adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

- Diet and lifestyle determinants of health or illness

The tools were originally intended for use with patients, but Jonas says they’re exactly the questions practitioners now need to ask themselves. He has adapted the original HOPE tool set so clinicians can “turn the lens onto themselves.”

“You can’t be a good healer unless you yourself are in a good place. Self-care is essential in healthcare. We need to provide resources so doctors and other medical professionals can do this without any kind of label or stigma. You should get credit for self-care practices, for structuring your practice so it (self-care) is a normal part of the way you practice medicine.”

Most clinics these days are a far cry from the health havens Jonas would like to see. To realize this vision will require not just individual commitment, but fundamental structural change in how we finance healthcare.

An End to FFS

He, and other primary care leaders, believe primary care’s future depends on a widespread shift out of fee-for-service (FFS) billing and toward global payment plans that provide capitated monthly per-patient payments covering whole-person health.

“The FFS approach keeps doctors on a treadmill that leads to moral injury,” Jonas told Holistic Primary Care, adding that “COVID has really ravaged” FFS-based primary care.

He says there are already good examples of global-payment primary care that demonstrate its viability—both clinically and fiscally.

One example is Oak Street Health, a for-profit company that operates 68 clinics in 9 states. Oak Street’s model works on full-risk capitation, and provides comprehensive primary care for Medicare patients. Each clinic can enroll up to 3,500 patients.

“They take care of the underserved elderly–people at the highest risk with fewest resources. They’re paid a sufficient amount to take care of these patients. They’re not paid for doing things. When COVID hit, they did not see a drop in income. They could pivot and put resources into what was needed to address the emergent crisis.”

Dr. Jonas also had high praise for Iora Health, a network of nearly 50 clinics in 9 states, that emphasizes care teams in a capitated global-payment environment that emphasizes health promotion and disease prevention for diverse patient populations. Unlike Oak Street, which is focused exclusively on Medicare, Iora has contracts with self-insured companies, labor unions, large insurers, and Medicare Plus plans.

Iora demonstrates that global payment models are not just for “government” payors.

“Fundamentally, it comes down to investment by the nation in delivering high-quality primary care. This (global payment) is how the payment system needs to shift,” Dr. Jonas said.

END