Balance is an essential concept in holistic medicine. The word is everywhere: we talk about work-life balance, balancing hormones and neurotransmitters, keeping an ideal acid-alkaline balance.

All of those are important. But the reality is, many people struggle with the much more basic issue of physical balance. Especially as people age, the ability to stay balanced on their own two feet becomes compromised. Poor balance leads to increased risk of injury, compromised mobility, and high risk of falls.

In this three-part series, I’ll explore the key muscle groups involved in achieving balance and stability, and share the exercises I’ve found most helpful when working with my clients.

One of the best remedies for balance problems is core training, the focus of this article.

The importance of core training cannot be overstated. Lack of connection to the muscle groups that comprise the body’s core results in poor posture and greater risk for falls and injuries. While the problems tend to show up later on in life, they actually begin much earlier.

The “core” is the center of the human body, consisting of most of the spine, and a network of muscles, tendons, ligaments that create the housing for the internal organs. Generally, the core is considered the torso and the supporting muscular network. But when teaching core-strengthening exercises, I include the shoulder complex and the gluteals, as these are important support systems for core strength.

Core exercises get a lot of attention among athletes and fitness enthusiasts. But there’s a lot more to it than developing showy six-pack abs.

The importance of core training cannot be overstated. Lack of connection to the muscle groups that comprise the body’s core results in poor posture and greater risk for falls and injuries. While the problems tend to show up later on in life, they actually begin much earlier. Core strength is essential for all age groups.

Though traditionally the “core” is considered to be the torso, I include the gluteals and the shoulder complex to my core training. The glutes are crucial for proper posture, balance, and low back health. They also pull down on the pelvis to keep it in alignment. Therefore, weak abdominals coupled with weak glutes lead to an imbalance in pelvic alignment.

I also include the shoulder complex in core training. Mobilizing the shoulder joints and the thoracic spine alleviates upper back and neck pain, and also reduces risk of injury and impingement in the shoulder. Strengthening and stabilizing all muscles around the shoulder complex improves posture and allows for full oxygen exchange as the ribs open and lungs can fully expand.

Also, rounded shoulders and forward leaning head are a common side effect of excessive sitting and overuse of computers and mobile devices. This causes a tightening of the anterior deltoids and pectorals and weakening of all the muscles of the upper back. It becomes difficult to keep the scapula in proper position because of the lengthening of the posterior core musculature.

This improper muscle balance relationship leads to compression of the lungs. Full oxygen exchange is then impossible. Strain of the neck and shoulder muscles can also lead to TMJ. When working to build core strength, it is vital to give attention to the upper back and shoulders.

Improving Proprioception

When I began my personal training career I quickly realized most of my clients had no idea what I meant when I said, “Brace and tighten your core.” Some did not even know what “core” meant.

These clients generally have poor proprioception, weak abdominal and gluteal muscles, kyphosis in the thoracic spine, and anterior pelvic tilt. They rely on their low backs to lift, twist, and bend. This results in lumbar pain, sciatica, and often shoulder/upper back pain as well.

When I’m able to help these people connect with and strengthen their core musculature it can make a major difference in their overall health, well-being, and quality of life.

So many people are disconnected from their bodies. They don’t know how their muscles work, and find it challenging to move through space smoothly and without pain. Even clients who have been lifting weights or playing sports for years often have little understanding of how their bodies function.

Education is Key

Education about which muscles do what is an important first step. By patiently teaching about the muscle groups, having clients touch their own muscles, and using visualization we are able to make neural pathways to muscles that my clients never consciously utilized before.

I start by teaching my clients about the Anterior/Lateral core muscles: Rectus abdominis, Internal oblique, External oblique, Transverse Abdominis (TVA), and the Pelvic floor. This brings their awareness to these key muscles.

The rectus abdominis or the “six pack” is the most visible of the core muscles. It lies on the surface of the anterior torso. The fibers of this continuous sheet of muscle run vertically, and provide anterior flexion of the spine. The rectus abdominis also pulls up on the pelvis to keep it in neutral alignment.

The internal and external obliques make up the sides or anteriolateral portion of the core. The muscle fibers slant like they are reaching into your pockets. These muscles aid in rotation and lateral flexion of the spine.

Underneath these muscles is the transverse abdominis (TVA). A sheet of muscle spanning the width of the anterior torso, these fibers run horizontally. This sheet of muscle is responsible for lumbar spine support, and acts as a girdle to compress the internal organs and keep them in place.

So many people are disconnected from their bodies. They don’t know how their muscles work, and find it challenging to move through space smoothly and without pain. Even clients who have been lifting weights or playing sports for years often have little understanding of how their bodies function.

When we speak of “bracing the core,” the TVA is the main muscle we are targeting. Being able to control this muscle will bring immediate improvement in posture and balance.

The bottom of the core is the pelvic floor. This sling-shaped group of muscles basically keeps our organs from falling through the pelvis, and it is essential for urinary and fecal retention.

Weak core musculature is common in many adults, especially women who have given birth. The stretching of the abdominal wall and the pelvic floor is traumatic for these muscles and can be a challenge to strengthen them.

Constant sitting and phone use coupled with improper lifting form creates muscle imbalances. This often generates pain in the body anywhere from feet to head, depending on how the body compensates for lack of core strength and stability.

Proprioception & Deep Core Training

My first session usually begins with simple posture exercises, and foam rolling. This brings awareness to the body and increases proprioception.

Proprioception means understanding where the body is in time and space. It is the foundation of posture and alignment. Unfortunately, many people have poor proprioception. It must be strengthened before we move on to lifting heavier loads, so to speak.

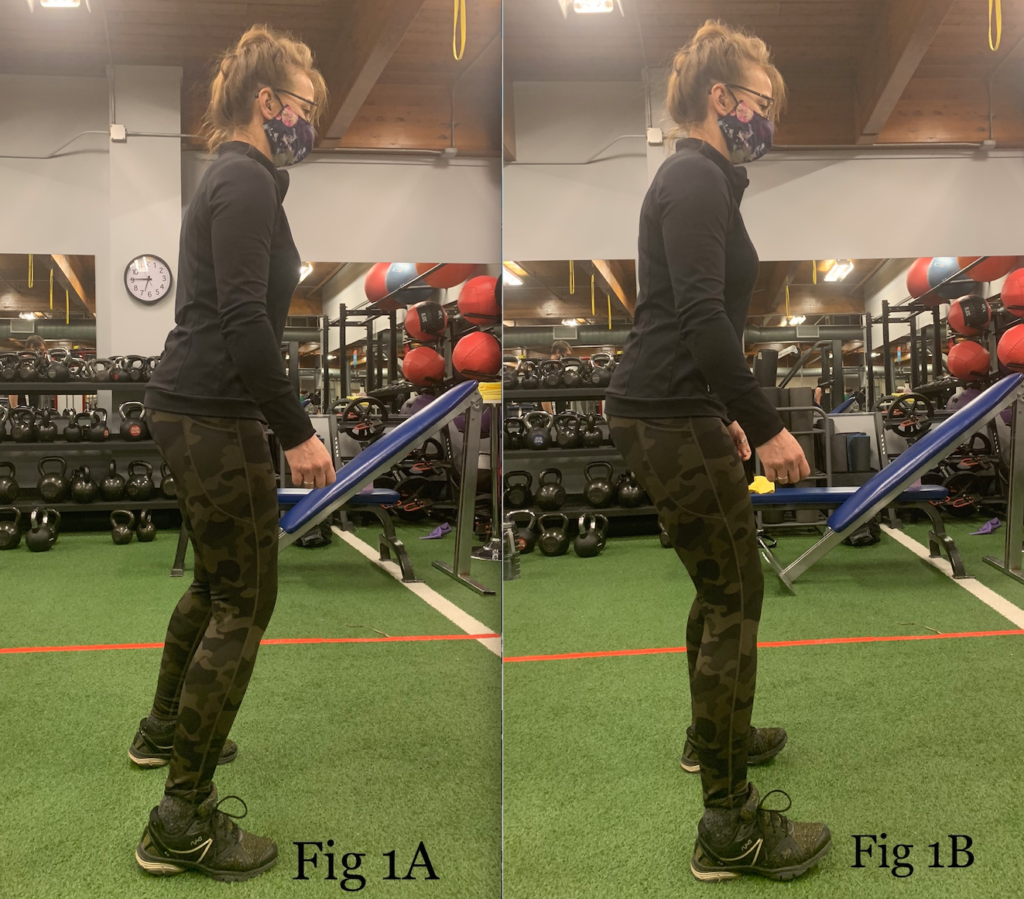

To begin posture work, I teach clients to take the “Athletic stance” using the following simple cues:

- Distribute weight evenly on both feet

- Shift weight onto heels

- Micro-bend the knees (soft, bouncy knees)

- Bring the pelvis into neutral alignment—Imagine laser beams emanating from the hip bones and hitting the front wall

- Bring awareness to the core (braced during exercise)

- Shift the shoulders down and back, away from their habitually scrunched position

- Lift the chest: Imagine a string between the chest and the ceiling, pulling the chest upward

- Hold head and neck in neutral alignment, ears over the shoulders

I like to give my clients the following Body Awareness exercise to practice on their own:

Every day, throughout the day, bring awareness to the body as you are sitting, standing, driving, and using your phone. Is weight evenly distributed on both feet while standing? Is it even on both glutes while sitting? Are the shoulders down and back, the chest lifted, neck and head in alignment? Is there excessive curving or flattening of the low back?

This creates a foundation of posture that is essential for building a stronger, healthier body.

These gentle corrective exercises may appear too easy at first glance. But every client I’ve trained has commented on how challenging these exercises are when they focus on particular muscles or muscle groups. The truth is, it takes repeated, concentrated effort for about 10 weeks to build a strong and conscious neural pathway from the brain to a particular muscle.

Waking the “Sleepy Butt”

Learning to shift body weight to the heels is particularly important, as it aids in posterior chain activation.

Most adults are quad-dominate, meaning that their hip flexors and quadricep muscles on the front of the hips and thighs are overactive, and the hamstrings and gluteals are underactive. I call this phenomenon “sleepy butt syndrome.”

In quad-dominant people, lifting, squatting, or stepping up utilizing the knee joints can eventually lead to a breakdown of knee cartilage, causing pain and damage in these joints. Once one or both knees are injured, overcompensation postures will lead to more pain and injury—in the ankle, hips, low back, and even up to the shoulders and neck.

In practice, it can be difficult to pinpoint exactly where or how a particular musculoskeletal or postural problem arose. Therefore, training the body as a whole system is the most effective approach. Within a comprehensive whole-body framework, it is vital to address individual muscle groups to build neural pathways that lead to increased proprioception. This in turn leads to more effective training in the gym, proper form when executing activities of daily living, and less pain and strain in everyday life.

Here is a set of exercises that I’ve found effective in helping clients strengthen their core muscles, increase their proprioception, and improve their posture:

Weight Shifts: Stand in an athletic stance. Keeping both feet firmly on the floor, shift weight to the toes/balls of the feet. Gently brace fingertips on a wall or chair can help with balance, if need be. Notice how the quads and the knees sense the weight, and how they activate.

Shift body weight to the heel of the foot, keeping the toes down. Notice how the hamstrings and the gluteals activate, alleviating the pressure on the anterior portion of the legs.

Shift weight back and forth, toe/heel for 10 repetitions.

Many patients will find it difficult to maintain balance while shifting, especially as they shift their weight to the heels. This indicates weak hamstrings and gluteals.

Standing Pelvic Tilts: Find the bony prominences on the front of the hips (the anterior superior iliac spines). Then with the thumbs, feel on both side of the spine for the bony prominences close to the spinal column (posterior superior iliac spines).

Visualize the pelvis as a bucket full to the brim with water. The goal of this exercise is to bring the bucket upright without spilling. Keeping soft knees, hold onto the pelvis with both hands. Tilt the pelvis forward, creating an exaggerated curve in the low back and spilling water out the front of the pelvic “bucket”. Then tilt the pelvis back as far as possible, flattening the low back and spilling water out the back of the bucket.

The point right in the middle of those two movements is the point of neutral alignment, where the bucket is upright and no water spills.

By going through full range of motion (ROM) of the pelvis, this exercise helps people become sensitive to that point of neutral alignment, which is important for supporting the spine.

Supine Pelvic Tilts: Lie comfortably on the floor with the upper body relaxed. Feet are firmly planted, knees are in line with the hip bones. As with the standing pelvic tilts described above, grasp the pelvis “bucket” with both hands. Tilt the pelvis up, curving low back, and gently push the low back down flat on the floor. Do one or two sets of 10 repetitions of this movement.

Patients will quickly notice that their abdominal muscles must activate in order to facilitate the pelvis pushing back into neutral alignment.

TVA Contractions: Lie on your back, with a gentle low back curve, and knees in line with the hip bones. With two fingers, find the hip bones and trace a line up the torso until fingers are in line or just above navel. Between the obliques and the rectus abdominis there is a space. Gently push the fingers down into that space. Close your eyes if desired, and visualize someone above you, ready to drop a ball onto your torso. It is a natural reaction to “brace” to protect the internal organs. Brace and hold for 2 seconds, breathing through this contraction. Do 2 sets of 10 repetitions to start, increasing volume and intensity as tolerated.

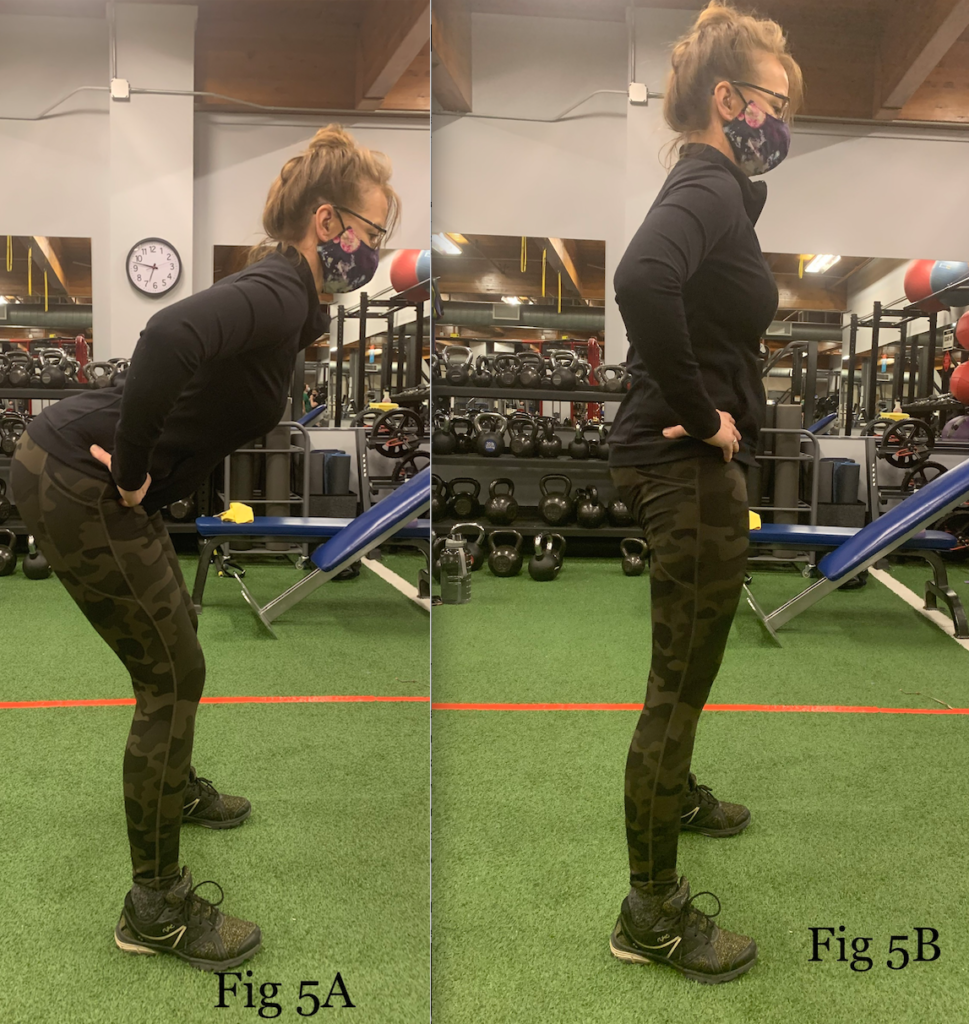

Hip Hinges: While standing in athletic stance, with the weight on the heels, sit the hips back as if trying to tap a wall behind you with the glutes. Visualize the hips like a hinge on a door. Feel the stretch in the back of the thighs–the hamstrings—as you push through the heels, and bring the hips back to neutral. Keep the chest open, and allow the knees to be soft, but do not bend them. This is not a squat! Perform 2 sets of 10-15 repetitions.

This exercise requires use of the glutes and hamstrings to facilitate the movement of the hips. It will not only bring awareness to the posterior chain, but also build strength and endurance in these muscles.

When doing this exercise, there is a tendency to bring the upper body as low as possible, even rounding the spine. This puts unwanted weight and pressure on the knees. You can counteract this tendency by keeping a gentle squeeze between the shoulder blades, visualizing the chest reaching to the front wall, and hips reaching for the back wall, and cuing into the stretch in the hamstrings. The hip hinge is the beginning of every leg exercise, including a variety of deadlifts, squats, and lunges.

Pelvic Floor Contraction (aka Kegels): In the same position as for the TVA contraction exercise, visualize the hammock-like sling of muscles at the bottom of the torso. Contract this as if stopping the flow of urine. Hold for two seconds, then release.

Do 2 sets of 10 repetitions, increasing in volume and intensity.

Pelvic Floor plus TVA Contractions: After doing the two previous exercises separately, it is possible to combine them. In the same laying position, first contract the pelvic floor, then the TVA. Hold both together for 2 seconds then release completely. Perform 10 repetitions. After repeated practice, you may want to do 2 sets of 10 repetitions, increasing time and reps as tolerated.

Again, while these exercises seem simple, they can be quite challenging especially for people who have significant imbalances, and who have not exercised in many years. I assure my clients that it is ok to struggle, and that overcoming the challenges will be worth the effort, because they’ll eventually be able to through life pain-free and enjoy a lifetime of attainable, sustainable fitness and health.

In the next part of this series, we’ll look at stabilizing and strengthening the shoulders, lumbar spine, and gluteal muscles.

END

Stacy Collier is an independent practice management and billing consultant based in Anchorage, AK. She is also a certified personal trainer with a special focus on Corrective Exercise Therapy, helping people living with low back, shoulder, hip, and knee pain. Stacy recently launched Attainable Fitness, LLC, her personal training and fitness coaching practice.