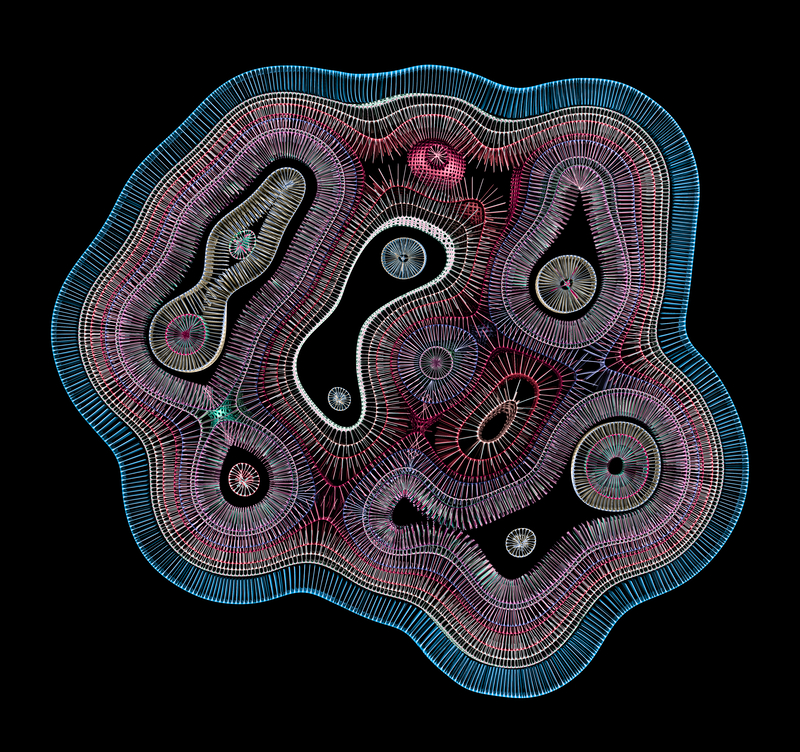

Your cells are talking to each other. Can you hear what they’re saying?

Physician and neuroscientist Jon Lieff, MD asks this simple yet profound question with his new book, The Secret Language of Cells.

In this new and fascinating work, Lieff tunes in to the biological conversions taking place deep inside the body to show how a myriad of different kinds of cells—from brain and blood cells to bacteria and even viruses—all use a common language to communicate.

Analyzing the current scientific literature on cellular communication, Lieff reveals that an ongoing transfer of vital information flowing between cells is what sustains the life of every organism on the planet.

Lieff holds that intercellular chatter is a key driver of the brain-body connection. Simultaneously, the conversations in which our human cells talk with other living cells in the external environment, influence our physical and mental health status in ways of which we are seldom aware.

Medicine of the future, Lieff predicts, will rely increasingly on our ability to decode the microscopic messages cells are continually sending one another. His engaging, illuminating depiction of cellular communication offers valuable insights to medical professionals and general science readers alike.

Defining Health and Disease

Integrative medicine pioneer Andrew Weil, MD describes Lieff’s work as “a new paradigm for understanding health and disease.”

What’s new is the recognition that complex conversations occurring in individual organs not only affect cells in the immediate area, but also in remote and seemingly “unrelated” body parts. It’s a basic principle of holistic and functional medicine that too often goes unacknowledged.

Medicine of the future, Lieff predicts, will rely increasingly on our ability to decode the microscopic messages cells are continually sending one another.

In the past, Lieff explains, scientists investigating health and disease tended to study the cells of a single specific organ. They might also look at nearby blood vessels or related nerves and hormones.

Recent advancements in cell biology are challenging that old perspective. We now know that illnesses and injuries initiate critical signalling exchanges between blood cells, the epithelial cells of various organs, immune cells, neurons, and microbes, both locally and in areas seemingly far from an organ that’s distressed.

A Harvard-trained neuropsychiatrist, Lieff’s exploration of cellular communication started in the brain, and neurotransmission is one of the clearest and most obvious examples of cell signaling. Neurons communicate by releasing and receiving chemical signals. They also convert sensory stimuli into electrical signals to send messages to other neurons.

But the intracellular conversations do not stop with the brain and spinal cord.

“Everywhere I looked, cells were talking to each other, just like brain cells, and these conversations determined biological activity throughout the body, not just in the brain,” Lieff says.

He soon realized that all processes in the human body––as well as in animals, plants, and microbe communities––are directed by group decision-making at the cellular level.

Lieff’s book is filled with vivid stories of the messages exchanged by cells, microorganisms, and viruses. During infections, for example, T cells send signals to neurons from the cerebrospinal fluid, telling the brain that it’s time for the body to rest. Gut cells communicate with bacteria to distinguish friend from foe. Cancer cells warn others about threats from microbes and immune cells.

Lieff wrote The Secret Language of Cells during a hiatus from work on his acclaimed website, Searching for the Mind, which featured weekly blog posts reviewing the latest scientific literature on neuroscience and cell biology.

A New View of Infection

If cells are the building blocks of living things, it is their intricate signaling strategies that truly bring them to life, Lieff posits. This has major implications when we consider phenomena like infectious diseases.

“The old view of infection says that it’s the amount of germs, the number of microbes that determine whether an infection is dangerous or not––but that’s not really the case,” Lieff told Holistic Primary Care. More significant than the quantity of pathogens is the response that occurs when organisms present in the body encounter a pathogen during an infectious encounter.

Viruses are communicating among themselves with small molecular signals that direct decision-making and determine group behavior. In this sense, viruses behave more similarly to living cells than we previously realized.

Microbes have immense power to intercept the intracellular conversations happening in the host tissues. Despite being much smaller and less complex than human cells, bacterial cells interact frequently and fluently with our cells.

That’s because they speak a shared biological language of electrical impulses and chemical codes. Many types of fungus, plants, and viruses are also fluent in these languages. This is not metaphorical or poetic; it is the simple truth of what’s happening at the cellular level.

Consider what goes on during the infection process, Lieff proposes.

“When infections occur, conversations between capillary cells, organ lining cells, neurons, immune cells, and platelets call for white blood cells and give travel directions to the infection site. Once at the site, neutrophils signal to other cells to organize the attack; following the attack, they can stimulate chronic inflammation. Deciphering these neutrophil conversations with capillaries, other immune cells, and tissue cells will provide the ability to stop infections more rapidly and avoid chronic inflammation in tissues.”

Insights From Cancer Cells

Some of the most significant insights about intracellular signalling have emerged from the study of one of humanity’s greatest scourges: Cancer.

Cancer cells are very good at communicating and coordinating with each other, and with the surrounding tissues. This is how they evade host defense systems, infiltrate tissues, induce angiogenesis, ensure their energy supply, and develop resistance to anti-cancer drugs.

They can trick neurons into sending signals for cell growth and cell regeneration that would normally be involved in tissue healing. They can manipulate platelets to provide cover from immune system attacks, and they can enlist certain types of immune system cells to live within the tumor colonies.

Cancer cells do all of this through a number of highly evolved and specialized communication mechanisms. Among them are:

♦ Exosomes: These are small membrane-bound sacs filled with information—RNAs, proteins, and peptides—and released from the cancer cells. When these exosomes arrive at their targets, the signals contained within radically alter the behavior of the cells in various ways that favor the cancer. One of the major advances in oncology over recent decades is the development of exosome-based blood tests to diagnose various types of cancer.

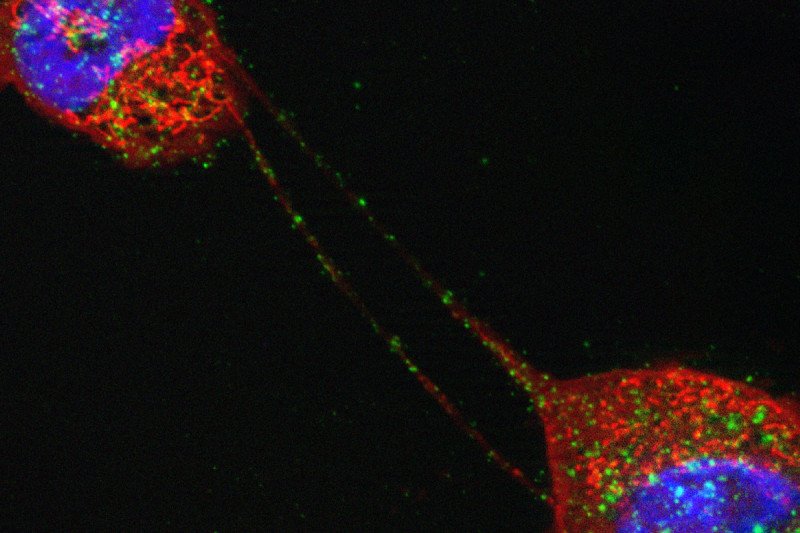

♦ Nanotubes: Cancer cells can also send signals through networks of nanotubes, which can rapidly convey genetic molecules, proteins, and even altered mitochondria that will specifically benefit other cancer cells by providing an increased energy supply.

♦ Secreted Signals: Like normal healthy cells, and microbial symbionts, cancer cells also use the more widely-known immune cytokines and brain neurotransmitters, to communicate with a wide range of cells.

Viruses: Inert or Alive?

Lieff contends that a better understanding of cell signaling processes could open valuable insights into the inner workings of life threatening diseases, including COVID-19.

Decades ago, breakthroughs in microbiology led to the discovery that “bacteria are smart, send signals, work together, and make decisions together.” We’ve since learned that bacteria communicate with cells in the digestive tract. They also synthesize essential nutrients. On the other hand, they can also cause conditions like leaky gut, among countless other problems.

It took longer, but researchers are now making similar discoveries about viruses. They are beginning to uncover the varied signaling structures and very elaborate lifestyles of several important viruses from COVID and HIV to Ebola and Herpes.

Viruses are the most prevalent life form on the earth, and interest in what they are and how they work is rising as a result of the coronavirus pandemic.

Recent findings indicate that, like cells, “viruses communicate among themselves with small molecular signals to make decisions and determine group behavior,” Lieff explains.

Traditionally, most scientists did not consider viruses to be alive. These tiny capsules of genetic material and protein cannot by themselves multiply without entering a living cell.

According to Lieff, the growing body of literature on virus signals and behavior is forcing us to update our “entire definition of life.”

Viruses act in remarkable ways. They can evade and counter elaborate attacks by far more complex human and animal cells. Each type of virus behaves uniquely, and with the explosion of new coronavirus research, scientists are rapidly starting to elucidate the genes, proteins, and behaviors that account for the remarkable tenacity of these entities that dwell on the threshold between the living and non-living.

One Enormous Brain Circuit

The field of intracellular communication also has profound implications for the field of neurology. He sees the nervous system as composed of two distinct but inter-related domains: the “wired” brain––the fixed circuitry of nerves in the brain––and the “wireless” immune system.

“Everywhere I looked, cells were talking to each other, just like brain cells, and these conversations determined biological activity throughout the body, not just in the brain.”

–Jon Lieff, MD

Stationary neurons and a mobile network of traveling immune cells in the tissues and blood vessels continually send messages back and forth, forming an inextricable link between the brain and the body.

Platelets in the blood, for instance, act as first responders in the presence of infections and trauma. They transmit signals that bring other cells to the site of infection or injury while fighting pathogens locally. Meanwhile, wireless signaling between immune cells and neurons can override regular brain functions to elicit the telltale “sick feeling” that prompts us to lie down when we’re unwell.

The integration of the wired and wireless brains “[show] clearly that there is really no separation at all” between brain and body. “In fact, the whole body is really one enormous brain circuit with constant conversations among all cells.”

Pathways for Integrative Healing

Neural circuits involving signals between neurons and immune cells might partly explain how some integrative therapies work. In acupuncture, for example, needles placed in the skin, away from blood vessels or neurons, stimulate T cells that send messages through the tissue and eventually reach nerves in distant parts of the body.

Similarly, during meditation, stimulation of the vagus nerve elicits changes in immune cells that can cause improvements in immune function––especially when practiced over time.

Lieff proposes that our definition of “the brain” needs to include both the wired neuronal circuits—what we conventionally call the “central nervous system”—and this wireless system of mobile immune cells. And that expanded definition will compel us to reconsider our notion of what constitutes “the mind.”

Written in a scientifically grounded but reader-friendly style, The Secret Language of Cells urges us to literally expand our minds to include the “ubiquitous signaling” between cells and tissues throughout the body, he says.

That the body and brain are—unbeknownst to our ordinary daily consciousness—constantly coordinating across large communication circuits “is a strong indication that there really is only one interactive system encompassing both.”

Future of Medicine

Learning the details of the “important conversations that influence our health makes understanding physiology and discovering new treatments more complex,” Lieff acknowledges. “But at least we know where to look and what to look for now.”

The wealth of findings emerging from cellular communication research could shape novel interventions for a host of human health issues including chronic inflammation and pain, weight loss, depression, cancer, and viral infections.

The more we learn how our bodies interact with ever-present bacteria and viruses in our environments, the sooner we’ll figure out how to live with them and perhaps even avert future pandemics.

Lieff hopes that by demystifying the scientific jargon of cell signaling, his storytelling will inspire readers with a sense of awe about the fascinating ways in which the smallest entities interact to create the vivid tapestry we call life.

END