The COVID pandemic, which began as a “big city” issue, is now upending daily life in rural areas that once appeared immune to its dangers.

I live in such an area, and I’m witnessing first-hand how the pandemic—and its economic, social, and political dynamics—can wreak havoc in a small country town.

As a former long-time resident of San Francisco, I relocated to Whitefish—a town of about 7,500 people in western Montana—in the Spring of 2019, just months before COVID swept the globe.

The allure of this beautiful state—especially to city dwellers—is undeniable. For those looking to trade urban living for a quieter life in the country, Montana makes for a magical destination.

Whitefish, and other towns like it, are prepared to handle vast numbers of seasonal tourists and small influxes of new transplants. Nothing could have prepared us for COVID and its aftermath.

An Early Success?

Montana is geographically one of the largest American states, though it is home to just over one million residents. Only its southern neighbor, Wyoming, and the state of Alaska have lower population densities than the Treasure State.

By contrast, New York City—an early COVID epicenter in the US—alone houses more than 8 million people.

Throughout the Spring, as caseloads rose in New York, Chicago, Washington, DC, and other major cities, Montana’s naturally socially-distanced population combined with strict and swiftly enacted public health measures, helped keep Montana largely corona-free. Early on, coronavirus seemed to be an urban problem.

Nonetheless, Montana’s Governor, Steve Bullock, was among the first in the nation to close schools in mid-March. A stay-at-home directive shuttering non-essential businesses followed shortly afterwards. The order included a mandatory 14-day travel quarantine for individuals arriving in Montana from outside the state.

The Western region quickly emerged as an early COVID success story. Over the first three months of the pandemic, Montana’s daily confirmed coronavirus count peaked at just 35 cases. Gov. Bullock reported in April that daily cases were dropping, and that outside of Montana, “very few [other] states in the country” showed declining numbers.

By midsummer, a dramatically different picture began to develop.

Segments of the Montana economy started reopening in May, and on June 1, Gov. Bullock lifted the previously required 2-week quarantine for travelers. A few weeks later, COVID cases soared past the state’s previous March peak—and they’ve continued to climb since then.

A confluence of factors, some unique to the American West and others more universal, are fueling the surge in Montana.

Tourism Takes a Turn

One key driver was a sudden rush of people flooding into the state to escape the virus.

Summer tourists, mixed with an influx of newcomers seeking to rent or buy properties in Montana, came in droves from across the US. With them arrived wildly divergent perspectives on public health, safety, and freedom.

Montana is home to two of the country’s top 10 most-visited National Parks. Yellowstone straddles the Montana-Wyoming border, and Glacier National Park stretches just below Canada in the northwest. Many local economies rely upon tourism to stay afloat.

In 2019, three million people—triple the state’s total population—visited Glacier Park alone. Prior to 2020, the park was experiencing record annual rises in visitation.

Within and beyond its parks, Montana’s wide-open spaces, sparse population, and boundless opportunities for outdoor recreation, added to its appeal as an attractive oasis from the coronavirus.

Towns like Whitefish are always awash in seasonal vacationers. But this summer, many travelers came to stay. Thousands of out-of-towners fled their home states to buy or rent in greener pastures across Montana. Sales of residential and commercial properties, as well as undeveloped land all skyrocketed, driving a massive real estate boom.

Local realtors reported selling properties sight unseen to wealthy out-of-state buyers. Recent data gathered by Glacier Flathead Real Estate identified 48% sales growth over 2019’s third quarter in Flathead County, with a massive 114% increase from 2020’s second quarter. There were 995 residential sales in 2020’s third quarter alone, versus fewer than 700 sales during the same period of 2019.

Those numbers might not sound huge by New York or Los Angeles standards. But keep in mind that metropolitan Billing—Montana’s largest city—has a total population of just over 180,000. A sudden real estate surge in small towns like Whitefish can destabilize established communities.

The inpouring of outsiders this year has put tremendous and unexpected pressure on vital local resources, among them our public education system.

School Surge

A “crazy hot” rental market meant that housing was not immediately available to everyone suddenly scouring Montana’s property listings. In highly sought-after ski resort towns, families arriving from out of state temporarily settled into motels and lodges, waiting for homes or rentals to come on the market. Some even used hotel addresses to register their children in local schools.

School districts across the state reported major increases in enrollment for the 2020-21 school year. The Big Sky district near Yellowstone saw a 15% increase in the number of kids registered to attend area schools. Closer to Glacier, the Whitefish School District added 95 children from out of state to its student roster.

In rural districts, even minor bumps in enrollment can overburden schools with limited resources. Some schools struggled with substitute teacher shortages as staff declined teaching positions due to fears about viral spread in the classroom.

Economic Disparities

The pandemic revealed and exacerbated Montana’s widespread economic vulnerabilities. As measured by median household income and per capita income, this is one of the poorest states in the nation.

Pandemic-induced business closures and job losses led to a huge jump in unemployment claims, forcing many to utilize food assistance programs.

Food banks, many already understaffed and under-resourced, witnessed striking increases in the numbers of community members in need of food. Some programs reported a doubling—or more—of hungry individuals and families.

As with the schools, many Montana food banks are scrambling to hire the staff needed to meet the rising demand, at a time when many people fear taking jobs that will expose them to the public.

In highly-touristed areas, most local businesses weathered the initial months without major losses. But the pandemic introduced another set of stressors for small business owners in particular.

One of these is the challenge of retaining employees. Some workers fear the virus itself, others fear the attitudes and behaviors of members of their own communities.

In the tiny town of Libby, one restaurant suspended dining service after guests repeatedly abused staff. According to the restaurant’s owners, the worst offenses included verbal harassment from tourists, and an incident involving regular guests who showed off their sidearms when asked to wear face masks inside the dining room.

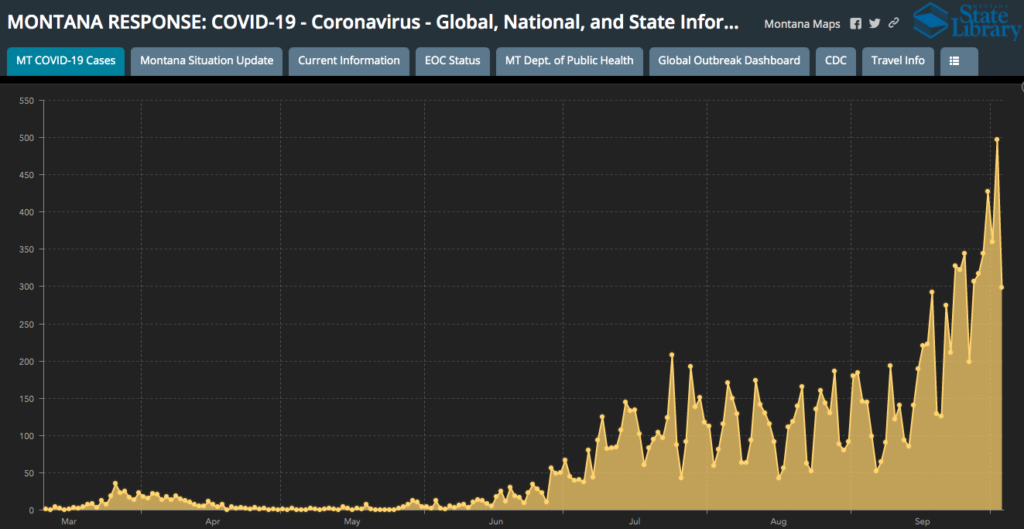

As the summer progressed, confirmed COVID cases in Montana climbed past previous high points. That trend continued into the Fall, with nearly half the state’s confirmed cases occurring in the month of September alone. By the end of September, our single-day new case total was broken and surpassed 11 times. The state did not hit its highest daily case total until October 7—and as of this writing, the count is still rising.

In a surprising twist from the pandemic’s earliest days, New York State formally added Montana to its COVID-19 travel advisory list in early September, requiring visitors from Montana to self-quarantine for 14 days once landing in New York.

Protecting Tribal Communities

As in other parts of the country, COVID has disproportionately affected Montana’s poorest and most marginalized citizens.

Nearly 90% of Montanans identify as White. The next largest group by race are American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) individuals, who comprise around 7% of the state’s total population.

There’s mounting evidence that the coronavirus disproportionately impacts Native American communities. In Montana, DHHS data show that AI/AN patients accounted for 16% of all COVID cases statewide—more than double the group’s representation in the state population.

This pattern is seen in tribal communities all over the country. In late August, the CDC issued a report indicating that the cumulative incidence of laboratory-confirmed COVID was 3.5 times greater among AI/AN individuals than among non-Hispanic Whites.

Members of tribal communities often live in multigenerational households, increasing the likelihood of transmission across age groups. High rates of chronic illnesses like diabetes and hypertension put Native Americans, especially elders, at greater risk of harmful complications associated with COVID.

In September, Montana’s 17,000-member Blackfeet Nation saw a spike in coronavirus cases. Hundreds of families on the Blackfeet Indian Reservation were required to quarantine at home for two weeks.

The shelter-in-place mandate came several months after a prior ordinance had restricted travel onto reservation land for the duration of the summer season. Initially, COVID cases on the reservation remained extremely low.

Closed Roads

The tribe’s land borders the east side of Glacier and offers numerous points of entry into the million-plus acre national park. Roads entering the park pass right through reservation lands. The Blackfeet Tribal Business Council voted in late June to close the roads along the park’s eastern boundary to help prevent the virus from entering its community.

The Blackfeet also imposed numerous other public health measures, many of which were more stringent than the state’s general ordinances. Tribal officials prohibited vacation rentals, closed all non-essential businesses and roads, and imposed a nightly curfew on reservation land.

The Blackfeet road closures eliminated access to roughly half of Glacier Park. But that didn’t stop masses of people from flocking there all summer long. The traffic restrictions simply funneled most visitors through a single main entrance in West Glacier, overwhelming those campgrounds, causing massive traffic jams, and creating unprecedented congestion both in and around the park.

Social Friction

Many Montanans bemoaned what they described as a tourist takeover of usually quiet areas. County law enforcement in the Glacier area reported an alarming increase in calls about conflicts between residents and visitors.

Denied access to Glacier Park, tourists spilled out into less-visited parts of the state, in some cases failing to abide by area land use rules. Some pristine camping areas were looted and trashed, threatening the health and safety of wildlife.

Lifelong Montanans described travelers and new arrivals as “outsiders” taking advantage of the rural terrain to suit their own personal interests with little regard for year-round residents.

Others celebrated the boost these summer travelers gave to the region’s economy. However, adding COVID into the mix dramatically changed the flavor of Glacier’s tourism this year.

Clinics Stretched Thin

When cases began rising in June, those who contracted the virus weren’t just lifelong Montanans—they also included travelers and newcomers who’d recently moved here. Their presence added strain to a public health care system already under pressure long before the coronavirus reached the western frontier.

Hospital capacity is a critical issue in any community, urban or rural. Are the area’s medical facilities equipped to handle a sudden upsurge in sick patients? In the back-country regions, most are not.

Like many other parts of rural America, Montana has for years faced significant shortages of medical professionals. Doctors, nurses, and mental health practitioners are in chronically short supply across the state. The US Department of Health and Human Services classifies more than 50 of Montana’s 56 counties as “Medically Underserved Areas/Populations (MUA/P)” and/or “Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA).”

For many Montanans, the nearest medical care is hundreds of miles away. Several counties do not have any practicing doctors at all. Transportation is a major barrier to health care access.

When a hospital in Billings was hit with a surge in COVID in the late summer, it had to bring in backup from out of state.

As of mid-September, Billings’ Yellowstone County accounted for 40% of Montana’s known cases, though it accounts for around 15% of the state’s population. Nurses, respiratory therapists, and technicians traveled in from three sister hospitals in Colorado to help relieve staff and keep the county’s hospitals running.

As in other parts of the country, many health practitioners here have shifted to telemedicine, a trend that’s likely to continue long past the COVID era.

But telehealth services aren’t always an option in remote rural areas like this. Huge swaths of Montana remain disconnected from the digital world. That’s part of the state’s appeal. But in today’s healthcare, it’s a major disadvantage.

Montana’s age demographics further limit the effectiveness of telemedicine. The state has one of the country’s oldest populations. Even in areas where patients can plug in, elders may resist transitioning to web-based medicine.

Pre-COVID, the Montana Hospital Association was already cautioning that “as our state ages, our health care needs continue to increase.” The pandemic has only amplified the problem.

Maskless in Montana

On July 15, the governor’s office issued a statewide directive requiring face coverings in most indoor spaces, and for certain outdoor events.

The mask mandate rapidly became a source of both contention and confusion among tourists and locals alike.

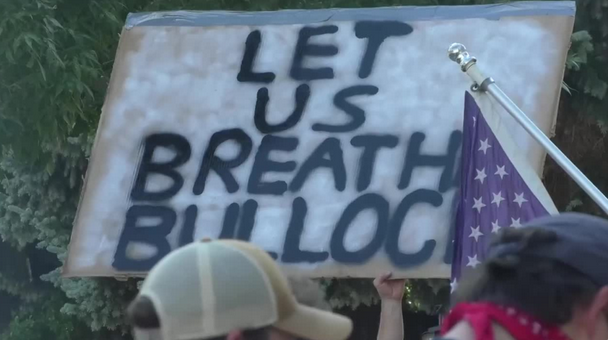

Resembling similar scenes playing out in small towns across the American West, many Montana residents simply refused to comply with the requirements. They cited Constitutional reasons for declining to wear masks, claiming that the mandate impinged on their personal freedoms.

While the state’s current governor is a Democrat, Montana residents are a predominantly Republican voter base. Political alliances deepened the sharp divide between the masked and the masked-not, raising new angles on the age-old question of what makes a “true” Montanan.

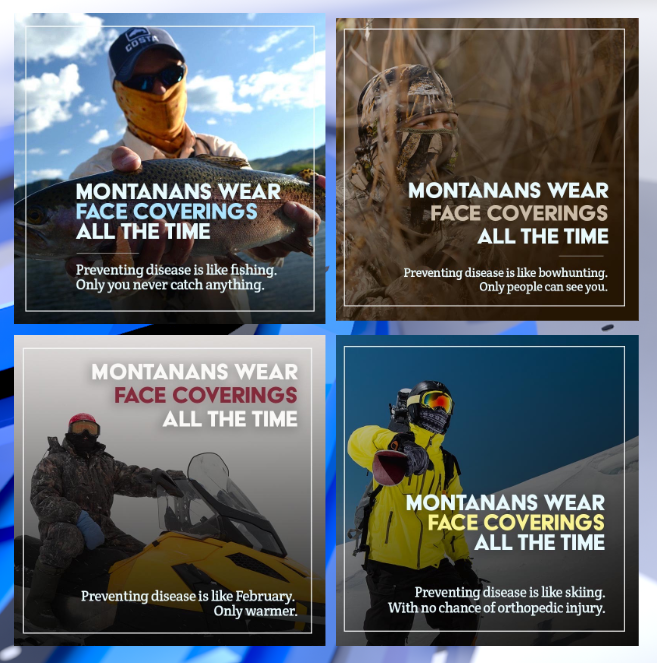

The state responded with local Mask Up campaigns aimed at normalizing face coverings, and linking mask use with good sportsmanship, respect for neighbors, and other core Western values.

But as new viral hotspots emerged, so did the number of heated anti-mask protests. In the seat of Flathead County, the town of Kalispell moved city council meetings to a virtual format after multiple in-person meetings were disrupted by groups of bare-faced anti-maskers protesting the state’s face covering mandates.

It wasn’t just long-time residents who resisted masking up. Tourists from all over the country arrived maskless in Montana, expecting that anything goes in the Wild West.

The situation was not helped by the lack of a coordinated national response, and the emergence of a patchwork of state-by-state policies that created uncertainty about what rules actually existed, and to whom they applied.

Patchwork Policy

More broadly, the authors of a recent MIT study argued that the nation’s uncoordinated opening, closing, and reopening of state and county economies “is making the COVID problem worse in the US.” Researchers looked at the impact of state-by-state re-openings between January and July and found “surprising and troubling results.”

The MIT team analyzed state-level COVID policies, data from over 22 million mobile devices, and the social media connections shared by 220 million Facebook users. They concluded that “reimposing local social distancing or shelter-in-place orders after reopening may be far less effective than policy makers would hope.”

The researchers further argued that in some states, the shutdowns were in fact counterproductive, unintentionally encouraging those in locked down regions to flee to reopened regions, taking the virus with them, and creating new hotspots.

“We’ve seen a patchwork of flip-flopping state policies across the country,” said the study’s senior author, Sinan Aral. “The problem is that, when they are uncoordinated, state re-openings and even closures create massive travel spillovers that are spreading the virus across state borders. If we continue to pursue ad hoc policies across state and regional borders, we’re going to have a difficult time controlling this virus, reopening our economy or even sending our kids back to school.”

As of early autumn, Montana has yet to flatten the curve of its first COVID wave. What will follow in the months ahead is of grave concern among local medical practitioners.

In October, a group of more than 280 Montana-based health care professionals issued an open letter urging community members to take the virus seriously and follow basic guidelines to prevent overwhelming the regional medical systems.

“COVID-19 is surging in our community and in Montana,” the letter explains. “The situation is more serious than it has ever been in our state. New case counts and hospitalizations are hitting record highs nearly every day and tragically more and more Montanans are losing their lives to this disease.”

As we brace for the winter season, the Montana experience serves as a cautionary tale to other rural regions assumed untouchable by the pandemic.

END