Stop what you’re doing and count to 65.

Stop what you’re doing and count to 65.

Are you there yet?

In that brief interval, someone somewhere in the US was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

That’s what the epidemiologic data tell us: every 65 seconds, someone develops Alzheimer’s—the dreaded neurodegenerative disease that is now the third leading cause of death in this country.

For women, the lifetime odds of having Alzheimer’s disease are now greater than the odds of developing breast cancer.

There’s no way to sugar-coat the realities of AD: in most cases it results in devastating alterations of memory, behavior, and thinking that progress until life becomes unlivable. By and large, drug research has failed to deliver a “cure”—or even an effective therapy for delaying or mitigating the cognitive changes.

But in recent years, deeper research into the pathogenic role of chronic inflammation is offering some cautious hope that through comprehensive holistic lifestyle interventions we functional medicine practitioners can help to slow or even arrest the progression of Alzheimer’s. In some cases, we might even be able to reverse the damage.

Untangling Alzheimer’s

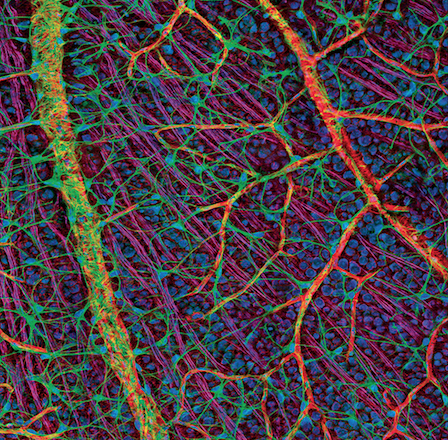

AD reveals much about the brain’s relationship to the immune system, and it exemplifies what can go wrong as a result of autoimmune reactions.

Basically, the disease is driven by two processes: extracellular deposition of beta amyloid-Aβ, and intracellular accumulation of tau protein. Aβ is the main component of the senile plaques—the thick deposits of beta amyloid that build up in the space between the neurons. Tau is the main component of neurofibrillary tangles—the twisted fibers that build up inside neurons. Both compounds are insoluble.

Aβ deposition is specific to and pathognomonic for AD, while tau accumulation occurs in other neurodegenerative diseases as well.

Scientists don’t know exactly what role plaques and tangles play in Alzheimer’s, but it seems they block communication among nerve cells. For this reason, beta amyloid was generally deemed to be “pathological.”

One of the key insights to emerge from the new wave of Alzheimer’s research is that amyloid deposition is the result of an immune reaction. In a sense, it is a protective mechanism gone awry.

Beta amyloid plaques are loaded with antibodies to various antigens—bacterial lipopolysaccharides, viruses, toxic peptides from poorly digested food, and many others. An activated immune system triggers deposition of beta-amyloid plaques. It’s a misdirected effort to protect the brain from perceived pathogens.

Leaky Vessels, Leaky Brain

The blood brain barrier (BBB) is responsible for blocking large molecules in the bloodstream from entering the brain. When healthy, the BBB is even finer and more “discerning” than the mucosal barrier in the intestine. But just like its gut counterpart, the BBB can also become compromised by infections and chronic inflammation.

This condition, which some functional medicine practitioners have dubbed “leaky brain,” is a breach of the BBB that allows macromolecules from the blood to sneak inside the brain. Loss of BBB integrity is an early biomarker for human cognitive dysfunction; it occurs long before the hallmark buildup of amyloid and tau protein begins.

Leaky brain capillaries turn out to be one of the earliest indicators of impending dementia. BBB breaches can now be detected by cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers, and even by neuroimaging.

A major multicenter study published last February shows that individuals with early cognitive dysfunction have capillary damage and BBB breakdown in the hippocampus, independent of Alzheimer’s Aβ and/or tau biomarker changes. This strongly suggests that BBB breakdown is an early signal for human cognitive dysfunction independent of Aβ and tau (Nation DA, et al. Nature Med. 2019; 25(2): 270-76).

This five-year study of 161 elderly people published in Nature Medicine showed that the subjects with the worst memory problems also had the most leakage, regardless of whether abnormal amyloid and tau were present. The capillary leaks develop very early in the disease process, often before the plaque buildup.

The emerging science on dementia suggests that if we can repair these leaks, we can slow down or even prevent the downstream cognitive consequences.

“If the blood-brain barrier is not working properly, then there is the potential for damage,” said co-author Arthur Toga, a director at USC’s Keck School of Medicine. “The vessels aren’t properly providing the nutrients and blood flow that the neurons need. And you have the possibility of toxic proteins getting in.”

Breaches of the BBB can come from head trauma, infection, toxic molecules, food sensitivities, and chronic inflammation in other organ systems.

As with other semi-permeable barriers, the BBB is able to quickly restore its integrity following sporadic, short-term injuries. This often happens within 4 hours. But with recurring or chronic insults, the BBB can no longer maintain its integrity.

A compromised BBB is unable to prevent passage of antigens into the brain. In response, the glial cells of the brain’s usually calm immune system become over-activated. They continue to fire, creating lots of collateral damage.

BBB Biomarkers

It is important to identify serum biomarkers that signal the loss of BBB integrity.

Look for:

- Antibodies to zonulin and to actin (a smooth muscle protein forming a cable network within the endothelial cells)

- Antibodies to lipopolysaccharides

- Antibodies to S100B and neuron-specific enolase.

These markers will help you to determine where a patient is on the scale of BBB integrity. High levels of these antibodies indicate damage to the BBB.

In some cases, it makes sense to test for antibodies to brain targets like transglutaminase 2, transglutaminase 6, and gangliosides.

If there’s reason to suspect that infections play a role—and this is a common scenario, it is reasonable to test for antibodies to Herpes simplex, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and other common pathogens.

Assays for antibodies to gliofibrillar acid protein, myelin basic protein, glutamic acid decarboxylase, alpha and beta tubulin, cerebellar antibodies and antibodies to synapsin may also be helpful.

To help our patients mitigate the risk of dementia, we need to identify the triggers of inflammation and BBB breakdown, and then develop comprehensive lifestyle inter ventions aimed at eliminating them, while at the same time creating the right environment for optimal neural regeneration.

ventions aimed at eliminating them, while at the same time creating the right environment for optimal neural regeneration.

Identifying Antigenic Triggers

There is no single “cause” of AD, but there are hundreds of triggers and contributing factors. These range from gluten to bacteria to herpes virus. What unites all of them is that they unleash a cascade of inflammatory autoimmune reactions that ultimately result in a breach of the BBB.

Dale Bredesen, MD, the director of the Mary S. Easton Center for Alzheimer’s Disease Research at UCLA, and Founding President of the Buck Institute—the nation’s first independent center for research on neurodegenerative disease—believes Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia are both preventable and reversible once the causes and triggers are addressed (visit www.holisticprimarycare.net and read To Reverse Alzheimer’s, Seek Its Triggers).

He holds that under conditions of chronic inflammation and BBB permeability, the brain’s natural balance shifts away from synapse creation and memory maintenance, and toward programmed neuronal death and memory pruning.

He and his colleagues have identified five separate categories of brain degeneration caused by more than 50 mechanisms (up from the original 37 he initially described in 2014).

Bredesen’s approach, which he describes thoroughly in his popular book, The End of Alzheimer’s, is a beacon of hope in an otherwise bleak clinical landscape.

In his clinic, Dr. Bredesen has reversed over 100 patients who had been suffering from cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease and now are back to living with their families and functioning at pre-diagnosis levels.

In essence, Bredesen has shown that AD is indeed reversible, if one addresses the root causes and eliminates the inflammatory triggers.

The key is to limit the production of unnecessary antibodies, thereby quelling inflammation.

Many factors contribute to the inflammation that drive AD: gluten, refined carbs, trans fats, chronic emotional stress, lack of exercise, sleep problems, nutrient-depleted diets, environmental toxins, electromagnetic radiation, trauma (like concussions), advanced glycation end-products (the fusion of proteins and sugars that result from charring, broiling, or frying foods), nutrient deficiencies (like vitamin D), insulin resistance, hormonal imbalances, diabetes, obesity, and microbiome dysregulation.

Each patient will likely show a unique combination of these factors. Much of the work of mitigating dementia is in identifying the specific factors that are most problematic in each case.

Type 3 Diabetes?

AD is connected to insulin resistance, prompting some functional medicine practitioners to refer to it as “Type 3 Diabetes.”

Under normal and healthy physiological conditions, once insulin has done its job of transporting glucose into cells, it is broken down by insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE). It so happens that IDE is also responsible for breaking down b-amyloid in the brain.

When someone is insulin-resistant, more IDE is required to degrade the excess insulin, and consequently, less goes to the brain. This means less breakdown of b-amyloid, which starts to accumulate in the intercellular spaces. Neuronal function is further compromised by the loss of ability to efficiently use glucose sugar as fuel.

Ed Goetzl, MD, at the University of California San Francisco has published some beautiful papers looking at neural exosomes in the blood. He looks specifically at a molecule called IRS-1 (Insulin Receptor Substrate).

In someone with normal insulin sensitivity, there’s a high degree of IRS-1 signaling, and a concurrent high degree of tyrosine phosphorylation. In conditions of insulin resistance, IRS-1 is down-regulated, and there is more serine and threonine phosphorylation.

Goetzl looks at this ratio to determine if someone is insulin-resistant or sensitive. He has found that 100% of people with AD are insulin resistant.

Infections Play a Role

Infectious pathogens, or substances produced by them, also play a role in dementia. Molds, Lyme-inducing spirochetes, Herpes, Babesia and others have all been linked to AD (read Gram-Negative Bacteria Implicated in Alzheimer’s Pathology).

Prescription drugs may also raise risk. Bredesen suggests that in roughly 15% of those with symptoms suggestive of AD, the problems may be secondary to medication side effects. Antihistamines, benzodiazepines, opioids, and antidepressants are of particular concern.

Drugs with GABA-ergic or anti-cholinergic activity also have a negative impact on cognition when used for long periods.

Leaky brain can manifest as symptoms like forgetfulness, brain fog, mood disorders, dementia, MS, and even Parkinsonism.

It is notable, though not surprising, that many of the factors that put our brains at risk are also damaging to the gut.

It is important, therefore, to look at the gut any time you are assessing a patient with neurocognitive symptoms. The intestinal mucosal barrier and the BBB are similar. If the gut is not working well, sooner or later the brain will follow down the path of dysfunction.

Changing Brains

Because AD is inherently multifactorial, the therapeutic approach must be individualized to each patient and his or her family.

That said, there are certain commonalities that you’ll have to address in most, if not all patients: improving insulin sensitivity and balancing gut bacteria are big ones.

Dr. Bredesen, Dr. David Perlmutter, and others in the new vanguard of AD care, generally recommend a plant-based, whole-foods, ketogenic diet. Periods of ketosis will usually help to improve cognition. Fasting and exercising, supplementing with medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs) and supplementing with exogenous ketones (ketone salts or esters), can all help to keep someone’s ketones up to provide brain support without increasing insulin resistance.

Intermittent fasting can also improve cardiovascular health, reduce risk of obesity and diabetes, normalize insulin and leptin levels, reduce cancer risk, and improve gene repair.

Elimination of wheat, dairy, and sugar are good general recommendations for people at risk of dementia, as is increasing intake of low-mercury wild fish, vegetables, and fruits.

In a 2015 study of 250 older Australians, researchers found that the less healthy their diets, the smaller the subjects’ left hippocampus tended to be. This is the brain region linked with emotional regulation and mental health. The finding was recently replicated in the Netherlands with 4,000 older adults.

A vegetable-rich healthy diet has the bonus benefit of reducing the risk of depression by 30%.

People who eat lots of vegetables, healthy fats and clean protein with moderate amounts of red meat, were less likely to have depression or anxiety disorders than those who consumed a typical western diet of processed foods, pizza, chips, burgers, white bread and sweet drinks.

Supplementing with detoxifying nutrients is also important in averting dementia. Folate, vitamin B12, vitamin D3, and fish oil are basics that improve brain functions. Nutrients that reduce inflammation and heal and seal the gut and BBB include: glutamine, probiotics, colostrum, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), found in green tea, vitamin C, lycopene, and turmeric.

Adaptogenic herbs are also important. Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera, 500 mg twice daily) is helpful. So are coffee berries or whole fruit coffee extracts, which can reduce amyloid while increasing brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).

Bacopa (250 mg twice daily) raises cholinergic function; Gotu Kola (500 mg, twice daily) can improve focus.

Other lifestyle factors that are important for brain health and reduction of dementia risk. Exercise is a big one.

Regular exercise, even at low to moderate intensity, can increase learning, improve neuronal plasticity, strengthen posture and stability, increase the number of neurons, promote neuronal survival, and delay both the onset and the progression of neurodegenerative diseases. It even has protective effects in individuals with the high-risk ApoE4 genotype. Aerobic exercise helps improve blood flow to the brain.

Healthy sleep is also very important. Some at-risk patients benefit from periodic use of melatonin supplements (2-5mg at night).

Minimize EMF: Some researchers have suggested that EMF exposure plays a role in the development of dementia. While this has not been definitively proven. There’s no harm in taking simple steps to reduce EMF, such as switching cell phones to airplane mode before bed, and turning off wireless routers at night.

Mind-Body Practices: Meditation, yoga, Pilates, prayer, positive self-affirmations and gratitude practices can all help to improve mood and reduce stress.

END