Among his many celebrated lines, Scottish economist Adam Smith–the original spokesman for capitalism—wrote in 1776: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own self-interest.”

Ahhh, the free market, in which our rational self-interests will keep all of us well fed and safe from exploitation, high prices, and limits on our freedom of choice.

Nowhere is the influence of the free market’s “invisible hand” more hotly debated than in American healthcare.

Our capitalist system seems to be failing healthcare, but proposals for single-payer are met with a wall—or should we say a wail–of resistance (mostly from the health insurance lobby) centered on the idea that single-payer health care would “limit competition” and thereby limit freedom of choice for consumers.

Those vociferous opponents of single payer also claim that it would impact the liberty of health care practitioners to make their own clinical decisions and set their own prices.

The insurance lobby, and the politicians supported by it, use the term “socialized medicine” as a rhetorical stand-in for rationed care, long lines, and generalized health care chaos. But somehow, they seem blind to the reality that the so-called “free market” for which they advocate has already led to rationed care, restricted choices, long waits for appointments, corporate control of clinical judgment, and plenty of chaos.

Monopolized Medicine

While private insurers claim to spare us from the evils of “socialized medicine,” their invisible hands are actually pulling us closer towards monopolized medicine, not moving us away from it. We are edging ever closer to single-payer healthcare, just not that single-payer.

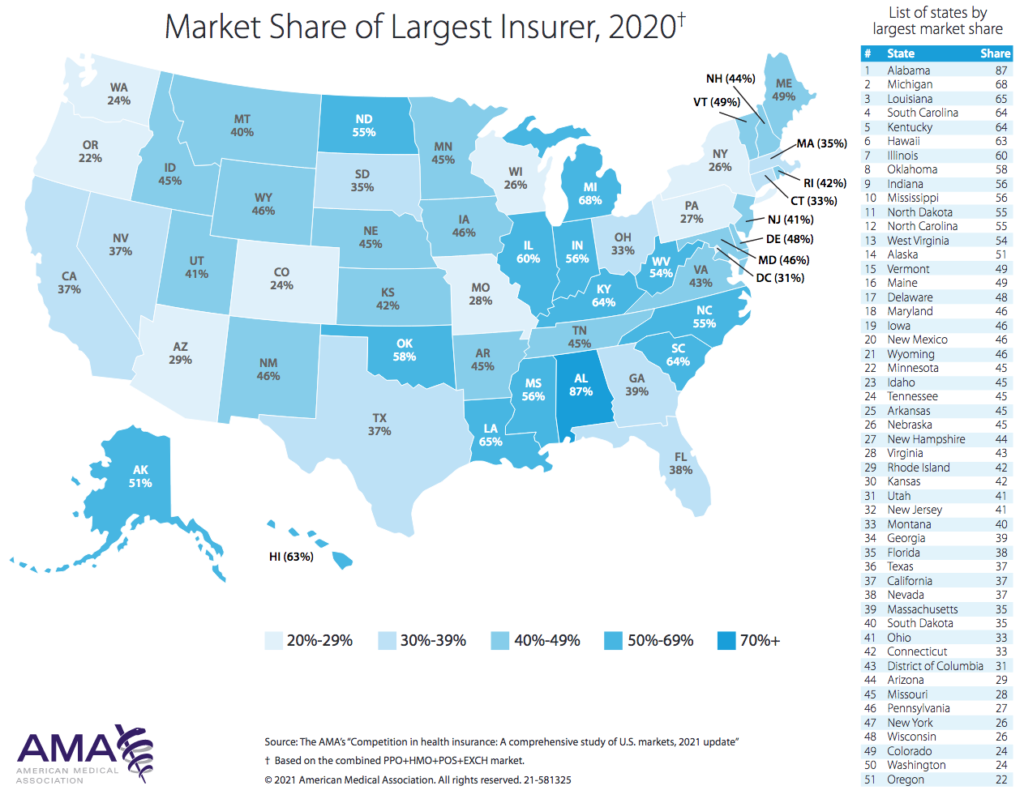

In 91% of markets, at least one insurer has market share of 30% or greater. And in 46% of the markets studied, a single insurer controls 50% or more of the total market.

–-Competition in Health Insurance: A Comprehensive Study of US Markets (American Medical Association, 2021)

This turn of events was born out in the American Medical Association’s recent report, Competition in Health Insurance: A Comprehensive Study of US Markets. The AMA, which has consistently advocated for universal insurance coverage while maintaining opposition to single-payer proposals, has published this report annually for the past twenty years.

The report analyzes market concentration and health insurer market shares for 384 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), along with data for individual states, and the US as a whole. It also lists the top ten health insurers (by market share) in the country.

To quantify levels of market competition the study uses Herfendahl-Hirschman Indices (HHIs)–a calculation used by the US Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission to inform decisions on whether proposed corporate mergers would create harmful monopolies. Put simply, the higher the HHI, the less competitive the market.

According to the AMA’s analysis, three quarters of all metropolitan areas in the US have health insurance markets that are “not competitive.”

In 91% of MSA-level markets, at least one insurer has market share of 30% or greater. And in 46% of the markets studied, a single insurer controls 50% or more of the total market.

Between 2014 and 2020, the percentage of markets that were highly concentrated based on HHI calculations increased from 71% to 73%. In 14 states, one single health insurance company holds greater than 50% market share.

Several markets that had already qualified as “highly concentrated” became even more so over that six-year span, and markets that were initially less concentrated also coalesced.

Consolidation Drives Up Costs

Concentration of market share in any industry generally is harmful to consumers, and health care is no different.

As insurers consolidate, they don’t have to compete with each other based on price, quality, or any other metric for that matter. They can raise premiums without fear of losing clients to competitors. For the same reasons, insurers can provide less coverage of medical services despite the increased premiums.

This tendency has been amply demonstrated in situations where health insurers have merged (Dafny L, et al. Am Econ Rev. 2012). As an example, the report cites a study analyzing a 1999 merger between Aetna and Prudential. That consolidation was clearly associated with rising premiums. Similarly, a 2008 merger between UnitedHealth and Sierra Health in Nevada resulted in a 13.7% marketwide increase in premiums in that state.

As a business, health insurance has high barriers to entry. It takes time to develop clinical panels and acquire enough “covered lives” to effectively spread risk amongst subscribers. Industries with higher barriers to entry generally favor larger firms and they tend to incentivize consolidation. But that leads to fewer options for consumers, not more. As markets consolidate, it becomes more and more difficult for new players to enter—furthering fueling the drive towards monopoly.

As insurers consolidate, they don’t have to compete with each other based on price, quality, or any other metric for that matter. They can raise premiums without fear of losing clients to competitors. For the same reasons, insurers can provide less coverage of medical services despite the increased premiums.

Another problem with health insurance consolidation arises from the so-called supply side: most physicians are completely reliant on the insurers for their livelihoods. We can’t make a living unless we can get on the panels of the plans that enroll our patients. If there are only one or two major carriers in an area, it is often a death knell to those practitioners who for whatever reason cannot get paneled.

It is a bitter irony that it is illegal for us as physicians to band together to negotiate reimbursement rates. The argument is that physician collective bargaining has the potential to limit the supply of medical services, patient choice, and negatively impact the quality of care patients receive. Yet insurance company consolidations produce exactly these negative effects but continue on unchecked.

Insurance industry dominance has also squelched the natural evolution of holistic, functional, and naturopathic medicine. Beyond lip-service about things like “wellness” and “lifestyle,” the major health insurers have shown little regard for alternative therapies, and most of these services are rarely (if ever) covered in any significant way—despite widespread and longstanding consumer interest in them.

Insurance industry leaders will trumpet their love of “free markets,” and the virtues of competition. In practice, they continue to do all they can to squelch free markets, minimize competition, and assert total market dominance.

Practitioners of holistic medicine are hard-pressed to get paneled and to get reimbursed for their services. While many patients choose to pay for these services out of pocket, large swaths of individuals who can’t afford them are left out.

Little Incentive for Innovation

A more competitive market might force insurers to consider wider coverage of so-called “CAM therapies.” Consumers increasingly demand a more holistic approach, and plans that acknowledge this could gain a competitive advantage. Presumably, healthier enrollees would cost less to insure over time than sick ones.

But with highly consolidated markets, and few insurance options, the large players have no need to seek creative, holistic ways to attract more patients to their particular plans. In fact, the opposite may be true—to protect bottom lines and maximize profits, monopoly insurers are incentivized to cover fewer services rather than more.

Health care costs continue to be a massive concern for the United States. In 2019, the we spent $11,502 per person on healthcare services—which amounted to 17.7% of GDP, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In spite of our astronomical spending, our health care system ranks below healthcare systems in other developed nations. That has been true for decades. As insurance conglomerates continue to consolidate and limit competition, the situation will get only worse, not better. We might end up paying more for even less, and practitioners of holistic medicine might be especially vulnerable to stingy coverage.

On the policy level, insurance industry leaders will trumpet their love of “free markets,” and the virtues of good ol’ red-blooded competition. In practice, they continue to do all they can to squelch free markets, minimize competition, and assert total market dominance.

The insurance lobby continues to vilify single-payer healthcare. But the big insurers continue their drive to monopolize markets in cities and in rural regions alike. In reality, most patients and practitioners have fewer choices now than ever before. All the patriotic insurance industry rhetoric about “freedom of choice” and “competition spurring innovation” does not change that fact.

END

Grant Jackson, MD, is an integrative family physician and journalist in Salt Lake City, UT, where he directs his own private practice, Jackson Integrative Health. He earned his MD defree in 2005 from the University of Utah, and did his residency training at Washington Hospital. He completed the University of Arizona’s Integrative Medicine Fellowship in 2016. He enjoys fly fishing, skiing, reading, cooking, and time with his wife Julie and their 4 children.