Debates about immigration policy and healthcare reform have dominated the US political landscape in recent years. At the intersection of these issues lie a number of important and troubling questions about the future of healthcare delivery.

Debates about immigration policy and healthcare reform have dominated the US political landscape in recent years. At the intersection of these issues lie a number of important and troubling questions about the future of healthcare delivery.

At issue is the vital role that foreign-born healthcare professionals play within the US medical system.

The simple truth is that immigrants make up a significant, though politically invisible percentage of the American healthcare workforce. Policies aimed at restricting and discouraging immigration, along with the sudden and seemingly unwarranted deportation of practitioners born outside the US, will likely have damaging repercussions for healthcare delivery at a time when the nation needs as many medical professionals as it can get.

Reliant on Immigrant Labor

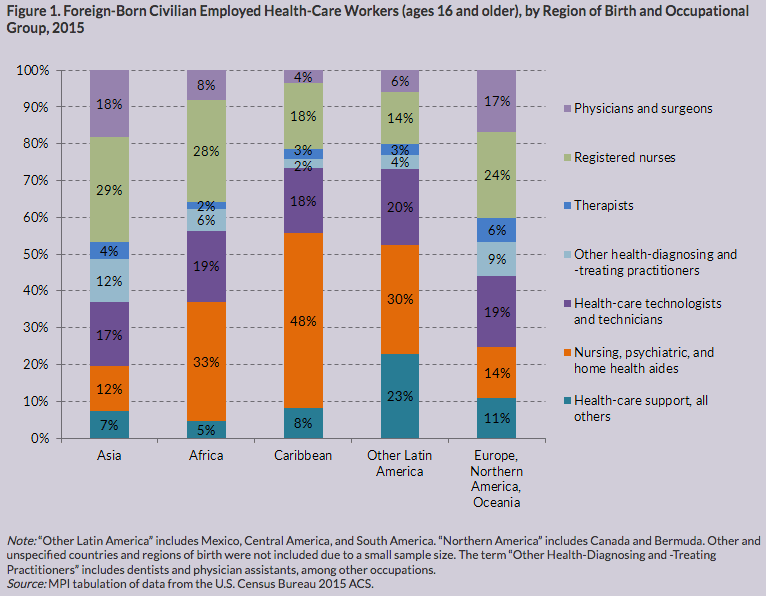

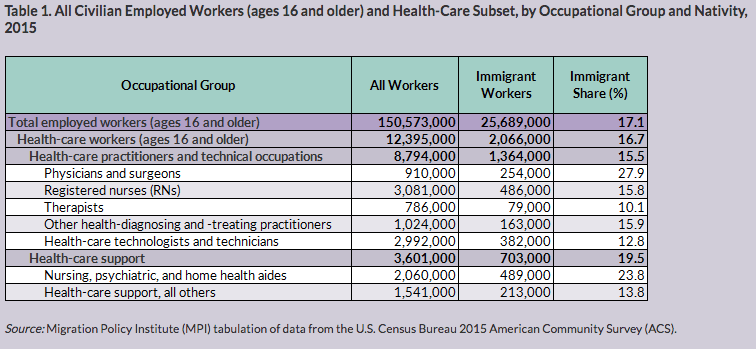

According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), people born outside the US represented about 17% of the total 12.4 million individuals working in healthcare occupations in 2015, the last year for which the institute has data. Immigrants fill not only critical physician and nursing positions, they also serve as dentists, medical technicians, home health aides, physician assistants, and researchers.

In certain medical specialties, the number of foreign-born practitioners is even higher. While exact percentages vary by state, immigrants comprise 28% of the overall pool of highly-skilled American medical professionals, which includes doctors and surgeons. They also fill 24% of all direct-care roles in the nursing, psychiatric, and home health fields. The need for these latter occupations––especially for home health aides––is projected to surge in the coming years, in step with the aging of the US population.

In the decade beginning in 2006, the number of immigrants occupying American healthcare roles rose significantly, from 1.5 million to 2.1 million by 2015. Many of these practitioners are immigrants who initially came to the US to attend medical school and who chose to remain in the country as practicing doctors.

For decades, the US has generally welcomed immigrants into our medical communities. The government even, in some cases, established special policies like the Conrad 30 visa waiver program, to help fill substantial gaps in the healthcare labor force by facilitating recruitment and retention of international clinicians.

A study published last year in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that, based on US Census data, non–US-born medical grads represent approximately one-fifth of practicing US physicians. Of immigrant medical grads who match into residency positions, approximately 60% are not permanent US citizens (Patel, Y. et al. JAMA. 2018; 320(21): 2265-2267).

These figures are just one indicator of how heavily our current medical system relies upon immigrant workers. Many observers fear that recent immigration policy changes, combined with an upsurge in anti-immigrant rhetoric, could dramatically––and even dangerously––affect the healthcare industry nationwide.

International Placements Declining

Anti-immigrant sentiments are nothing new in the US. Throughout its history, there have been periods when the nation rolled out the welcome mat, and others periods when it slammed the door. The medical world has never been immune to this phenomenon.

Up until the 1950s, many US medical schools had strict quotas on the numbers of Italian Catholics, Blacks, and Jews they would admit (for a fascinating and prescient look at the anti-Jewish med school quotas and their negative impact on American medicine in the last century, read this 1953 article by Lawrence Bloomgarden).

“A February 2018 report detailing physician placements shows that the percentage of internationally-trained doctors placed in US healthcare jobs dropped from nearly 32% in 2016, down to 24% in 2017.”

Today, controversial travel bans, discrimination against targeted ethnic groups, and lengthier visa application processes are deterring international medical practitioners from seeking American jobs. This new reality is especially troubling, given the projected physician shortages and a mounting need for a wide range of healthcare professionals.

Today, controversial travel bans, discrimination against targeted ethnic groups, and lengthier visa application processes are deterring international medical practitioners from seeking American jobs. This new reality is especially troubling, given the projected physician shortages and a mounting need for a wide range of healthcare professionals.

A February 2018 report from the Medicus Firm detailing physician placements shows that the percentage of internationally-trained doctors placed dropped from nearly 32% in 2016, down to 24% in 2017.

“The reason behind this trend is unclear, especially since the physician workforce demographics have not changed as such,” the report reads.

Prohibitions on international travelers from select countries could be a partial explanation. Travel bans instill a widespread sense of fear and intimidation, both among foreign-born health professionals already practicing here, as well as international practitioners who might otherwise consider pursuing health careers in the US.

Then, there is the hurdle of obtaining the appropriate documentation required to study, live, or practice medicine in the US. In 2017, 6.3% of all physicians placed came to the US on either a J1 exchange visitor or H1-B visa, the two main methods of entry for foreign-born medical students and graduates.

H1-B visas are reserved exclusively for highly-skilled professionals with, at minimum, the US equivalent of a 4-year bachelor’s degree. They are issued by lottery only.

While we’ve not yet seen Trump administration policy changes directed specifically at healthcare professionals, there’s no question that qualified applicants are suddenly encountering a lengthier and more complicated visa application process. Foreign-born medical grads who receive job offers from potential employers but cannot obtain visas quickly enough to legally remain in the US, risk having to either forfeit the offers or accept, knowing that they might be forced to leave the country––and their patients––very abruptly.

Fueling the Physician Shortage

The current immigration clampdown is occurring at a time when the US needs needs more medical professionals, not fewer.

A 2017 report published by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) details a projected shortage of up to 104,900 doctors by 2030. For the third year in a row, the AAMC estimated, demand for physicians will continue to grow faster than supply, leading to an anticipated total shortfall of between 34,600 and 88,000 doctors in 2025. That number could continue to increase significantly by 2030.

In a press release, the AAMC’s leaders state that the doctor shortages will likely have a profound impact on patient care.

“The nation continues to face a significant physician shortage,” said AAMC president and CEO Darrell G. Kirch, MD. “As our patient population continues to grow and age, we must begin to train more doctors if we wish to meet the health care needs of all Americans.”

In an already overburdened system, a shrinking doctor base could put further strain on a rapidly aging population that’s expected to live longer than previous generations did.

The American Medical Association (AMA) has also expressed concerns about the “unintended consequences” of the current  administration’s immigration policy changes.

administration’s immigration policy changes.

In a February 2017 letter to then-Secretary of Homeland Security John Kelly, AMA CEO James Madara, MD, outlined a number of concerns pertaining to President Trump’s executive order, “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” widely referred to as the Muslim ban.

The Supreme Court upheld the latest version of the travel ban in a 5-4 decision in June 2018, allowing the administration to legally refuse entry to immigrants and visa holders from Iran, Libya, North Korea, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. This ruling solidified the order’s third iteration as permanent immigration policy, creating significant new barriers for doctors, nurses, home care aides, and other healthcare professionals from those countries.

Many of our nation’s physicians––like practitioners across the broad spectrum of health specialties––are from countries named in the travel ban.

“While we understand the importance of a reliable system for vetting people from other nations entering the United States, it is vitally important that this process not impact patient access to timely medical treatment or restrict physicians and international medical graduates (IMGs) who have been granted visas to train, practice, or attend medical conferences in the United States,” Madara wrote in his letter to Secretary Kelly.

On behalf of physician and medical student members of the AMA, Madara also expressed concerns that the travel ban was negatively impacting, “both current and future physicians as well as medical students and residents who are providing much needed care to some of our most vulnerable patients.”

Widening the Gaps

Not only do immigrants represent a major portion of the nation’s total healthcare practitioners, they regularly take jobs in regions that struggle to recruit US-born clinicians.

“Many communities, including rural and low-income areas, often have problems attracting physicians to meet their health care needs,” Madara explained. “To address these gaps in care, IMGs often fill these openings.”

Many IMGs enter the US on visas that permit them to stay in the US if they commit to working in underserved areas for at least three years following residency. Young physicians born outside the US are more likely than their US-born counterparts to practice outside major metropolitan areas; they frequently serve in rural communities marked by doctor shortages.

Many IMGs enter the US on visas that permit them to stay in the US if they commit to working in underserved areas for at least three years following residency. Young physicians born outside the US are more likely than their US-born counterparts to practice outside major metropolitan areas; they frequently serve in rural communities marked by doctor shortages.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has also found that IMGs are more likely than US medical grads to serve patient populations that use Medicaid or the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) as their primary payment sources.

As in other industries, immigrant medical professionals willingly step into roles their American peers evidently aren’t as keen on filling.

Furthermore, immigrant physicians provide excellent quality of care.

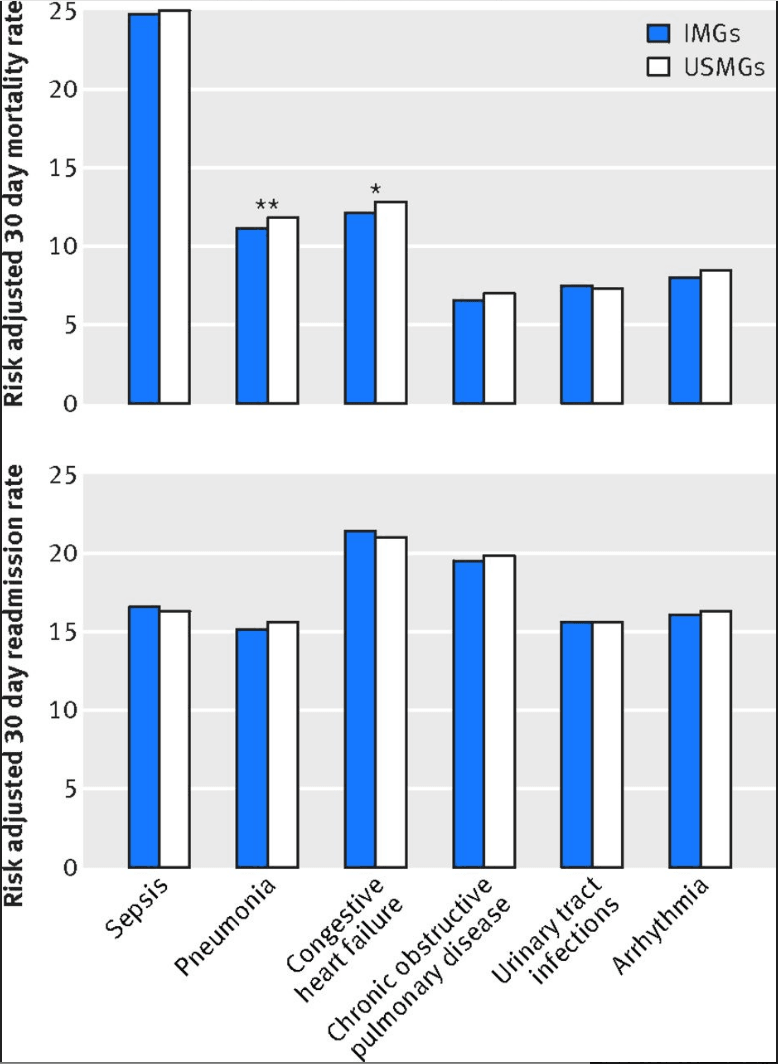

A 2017 study published in the British Medical Journal showed that the patients of foreign-trained doctors had better mortality outcomes than those treated by physicians trained in American medical schools. Investigators found that “patients treated by the international graduates had lower 30 day mortality than those treated by the US graduates.” That’s especially impressive given that the patients of immigrant physicians also showed slightly higher rates of chronic conditions.

The researchers speculate that “international graduates who are successful in the US matching process might represent some of the best physicians in their country of origin,” offering one possible explanation for the observed outcomes stats (Tsugawa, Y. et al. Brit Med J. 2017; 356: j273).

ICE Clamps Down on Clinicians

While the Trump administration’s immigration policies primarily emphasize unauthorized immigrants and their families, they nevertheless affect health practitioners and other skilled individuals who have been in the country for many years, and whose professional expertise overwhelmingly benefits their communities.

In a number of recent high-profile cases, immigrant medical professionals who provide vital services have been arrested, threatened with deportation, or denied entry into the US.

In one March 2017 incident, immigration officials abruptly informed two Indian doctors practicing and living legally in Houston, Texas, that they must leave the United States in 24 hours, with no advance warning.

A married couple, neurologists Pankaj Satija and Monika Ummat were stunned by the sudden news that they could no longer extend their temporary permission to remain in the country while awaiting permanent authorization, as they had done for years. Both had green card applications sponsored by their employers that were pending judgment for years. Owing to an acknowledged backlog in green card request processing that dates back to 2008, the government had granted provisional legal status to the couple–and to others in their situation–until their applications are officially approved.

The Houston Chronicle reported that Satija, a founder of the Pain and Headache Centers of Texas, performed an estimated 200  operations each month. Ummat was an epilepsy treatment specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital. The doctors had two young children, both born in the US.

operations each month. Ummat was an epilepsy treatment specialist at Texas Children’s Hospital. The doctors had two young children, both born in the US.

In October 2016, Satija and Ummat took a trip to India to visit his ailing father. On their return, they were stopped at the airport on grounds that their travel documents had expired, though officials at the airport when they left the US failed to notice this. They were permitted to re-enter the country and they returned to their home and their clinics. Five months later, however, they were abruptly informed that they were being deported.

Customs and Border Patrol officials, claiming that the couple was no longer authorized to stay in the country, and refusing to consider the case on an individual basis, ordered Satija and Ummat to return to India–their country of origin–within 24 hours, leaving their children–and their patients–behind.

Neither of the two physicians had ever even gotten a parking ticket, yet they dutifully reported to US Customs officials at Bush Intercontinental Airport for deportation, before they were informed that CPB would grant them a 3-month “humanitarian parole” to give the couple more time to “sort out their paperwork.”

Satija and Ummat were apparently able to resolve their immigration status, and have lived and practiced in the Houston area since. However, the incident was a clear inidication that CPB was fully prepared to uproot and deport two highly qualified physicians–and separate them from their children, rather than simply inform them that there was a paperwork problem that needed resolution.

In its coverage of the case, the Houston Chronicle notes that Harris County–one of the three Texas counties comprising metro-Houston–is the county with the largest proportion of foreign-born physicians: 41.2% of all Harris County doctors were born outside the US.

Another story that received significant media attention is that of Lukasz Niec, a Polish-born internist practicing for decades at multiple hospitals Kalamazoo, Michigan. Niec immigrated to the US with his family from Poland as a small child, became a lawful permanent resident, and eventually attended medical school in Michigan, where he married and had two children, as well as a stepdaughter.

A permanent Green Card holder, Niec had lived in the US for 40 years, when Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers arrested him at his home in January 2018, threatening deportation back to Poland–a country he hardly knew. He was taken from his family in handcuffs, and spent more than two weeks in Calhoun County jail–an ICE detention facility–before being released on bond.

As detailed in a Washington Post story, according to Niec’s “notice to appear” from the Department of Homeland Security, his detention stemmed from a misdemeanor for property damage and theft–he and several friends had defrauded ATMs with a “misplaced” card — that took place in 1992, when Niec was 17 years old. ICE’s decision to target Niec may also have arisen from a series of police investigations regarding allegations of child abuse against Niec. A Wayne County Circuit Court dismissed those allegations as unsubstantiated.

As detailed in a Washington Post story, according to Niec’s “notice to appear” from the Department of Homeland Security, his detention stemmed from a misdemeanor for property damage and theft–he and several friends had defrauded ATMs with a “misplaced” card — that took place in 1992, when Niec was 17 years old. ICE’s decision to target Niec may also have arisen from a series of police investigations regarding allegations of child abuse against Niec. A Wayne County Circuit Court dismissed those allegations as unsubstantiated.

Last July, Niec petitioned outgoing Michigan governor Rick Snyder for a full pardon. Synder granted the request a few days before Christmas, issuing a pardon that may abort the deportation proceedings. Niec’s case remains unresolved.

Whatever his past misdeeds, Niec maintains a sterling reputation as a physician in his community. A number of his medical colleagues have stood with him or written letters of support. Among them is Dr. Michael Raphelson, who works with Niec at the Bronson Methodist Hospital.

“It seems like every night we’re seeing innocent people being ripped away from their family for some vague immigration laws and a confusing immigration system that hasn’t been fixed,” Raphelson wrote.

Deportation of legal residents for low-level offenses did not begin with the present administration, and holding offenders accountable for their crimes is core to maintaining a safe and healthy society. However, under prior administrations, immigration authorities did not prioritize the removal of minor offenders, but instead focused on known violent criminals.

Today, revised guidelines encourage immigration officials to detain a broader range of potential deportees, from individuals with no criminal records to those who’ve lived in the US for most of their lives, started families here, and know no other home.

The tactic of removing any immigrant, even in minor cases of misconduct like the overstay of a work visa, is a questionable one––especially when it threatens individuals who otherwise present no threat and are active, contributing, positive members of their communities. The stated rationale for restricting immigration is to protect Americans––but if medical professionals who literally save lives are now living in fear of arrest or deportation, who are these policies really protecting?

Diversity is Strength

The US population is not just aging, it’s also becoming more ethnically and linguistically diverse. Greater diversity means greater need for culturally appropriate healthcare services.

“The current trend is that there is a gap between the languages that health professionals speak, and languages of their clients and patients,” said Jeanne Batalova, PhD, Senior Policy Analyst at the Migration Policy Institute. “This is an area where immigrants fill an important hole.”

Foreign-born health workers bring not only language competency, but also invaluable cultural awareness, attention to mental health issues, and local medicine traditions, into their communities. This helps build a crucial level of trust between practitioners and their patients, who themselves might also be immigrants, Batalova added.

Within the realm of holistic and functional medicine, the strange dynamics of immigration policy become even more strange. Many of the core principles of holistic medicine derive from ancient medical traditions that were brought here by immigrants from countries and cultures that are now being vilified.

“The collective struggle that new immigrants cope with in 2019 requires that they face institutional inequities and injustices, which have been heightened to inhuman levels in the Trump era,” said medical anthropologist Meg Jordan, PhD, RN, CWP, who is also Professor and Chair of the Integrative Health Studies program at the California Institute of Integral Studies.

“The alternative healers that immigrate here, such as Meso-American curanderos, Hmong healers, shamans, and more, dedicate their  lives to healing their communities––mind, body, and spirit. Their work is part of a critical, informal defense system that restores a sense of meaning and belonging, when disruption and social dislocation have been oppressive and physically and mentally harmful,” Jordan told Holistic Primary Care.

lives to healing their communities––mind, body, and spirit. Their work is part of a critical, informal defense system that restores a sense of meaning and belonging, when disruption and social dislocation have been oppressive and physically and mentally harmful,” Jordan told Holistic Primary Care.

Tereza Iñiguez-Flores, a Mexican-born folk medicine practitioner, explained the importance of holistic healers who serve as guides in their communities. They teach their patients far more than just self-care techniques; in many cases, they serve almost like informal patient advocates, educating recent immigrants on how to navigate the US medical system.

International healers work as nutritionists, herbalists, counselors, and advisors. They also provide “sacred spaces for folks to feel safe to release the stress, fear, and trauma” that so often influence overall health and wellness.

“After many years of backed-up research, it has been proven how essential traditional folk medicine is to the wellbeing of our communities,” said Iñiguez-Flores, whose practice reflects aspects of the Curanderia healing system. She pointed to factors that conventional healthcare often fails to address, like “spirituality, self-empowerment, and trauma healing, as well as understanding the importance of this combination for overall wellbeing.”

“Traditional folk medicine focuses on all of these absent services. Because of this, many health professionals who work with immigrants are gathering teachings from their traditional roots to integrate into their profession as healthcare practitioners. The awareness and understanding to how important it is for individuals to feel a part of, to have a voice, to be understood, and to have access to integrative medicine to bring overall wellness, is what has created significant impact in our communities,” she proposed.

“I see us growing as integrative healing practitioners and building stronger, healthier communities that are being held with heartfelt support,” Iñiguez-Flores added.

In an ideal world, governments would work to ease the journey for practitioners who strive to heal suffering people and broken communities. In reality, “alternative healers are often people of color who have moved away from systems of medical pluralism in their foreign land, only to find themselves operating outside the law and dodging exposure,” in the US, Jordan explained.

“Immigration reform should take into account not just the waves of families seeking refuge, but the healing practitioners who help rebuild their lives,” she urged.

END