If the idea of utilizing parasitic worms as immune system modulators makes you squirm, you’re certainly not alone. Sure it sounds strange, but the use of “purposeful parasites” is not as far-fetched as it seems.

Researchers like William Parker, PhD, of the Division of Surgical Sciences at Duke University, believe certain types of helminths can be helpful in treating immunological, gastrointestinal, autoimmune, and even cognitive disorders.

Helminths have a bad reputation, for a good reason. Hookworms, tapeworms, Guinea worms and others still cause a tremendous burden of disease and disability. Worldwide, worms are among the most common pathogens.

But like the microbiome, the relationship between humans and helminths is quite complex. Many worms are indeed pathogenic, but others may be helpful. Our modern quest to sterilize our food may be contributing to the burden of chronic inflammatory diseases plaguing industrialized nations.

Parker and other vermiphiles believe that in eliminating food-borne pathogens we’ve also vanquished helminthic symbionts important for our health.

Talk about opening a can of worms!

Helminth therapy is not a new idea. It first inched its way into medical literature in 1976, when English parasitologist, JA Turton, sought to cure his own allergies with the use of hookworms. Turton published his personal experience, revealing that he remained allergy-free as long as he maintained a healthy hookworm colony in his gut (Turton, Lancet, 1976, 686).

Since then, a number of studies followed Turton’s, some corroborating his findings while others lacked statistical significance. To date, the available data have not swayed the majority of mainstream physicians or, for that matter, the Food and Drug Administration, which does not currently recognize helminth treatment as a proven modality. FDA takes a quite restrictive view on the subject.

Why Worms?

The ideas behind helminth therapy align with the so-called Hygiene Hypothesis—the notion promoted by epidemiologist David Strachan that lack of early-life exposure to microorganisms and parasites predisposes industrialized people to allergic, inflammatory, and autoimmune diseases.

Parker says he disfavors hygiene hypothesis terminology, not because the core principle is wrong, but because it describes only one facet of the disconnect between our current mode of living and that of our ancestors.

It’s not just that we sterilize our food. We also eat monocropped produce; we have less contact with the soil; we are less likely to have been breastfed; many of us were born via C-section; most of us have been exposed to antibiotics. In short, modern life has introduced many major disruptions into our relationship with the microbial and helminthic worlds.

No doubt, these changes have been beneficial. But they’ve also created problems. Our immune systems co-evolved with certain microbes and helminths for thousands of years. Over a mere century, we’ve totally changed the immunological game.

In a thought-provoking 2015 review of helminth therapy for inflammatory disorders, Helena Helmby of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, notes that:

“Parasitic helminths have evolved together with the mammalian immune system over many millennia and as such they have become remarkably efficient modulators in order to promote their own survival. Their ability to alter and/or suppress immune responses could be beneficial to the host by helping control excessive inflammatory responses.”

Humans generate a strongly polarized Th2 reaction during helminth infections. As a result, this reaction can modulate Th1 immune responses to unrelated antigens, diminishing the strength of the immune response against secondary infections.

Scientific discussions on the topic highlight the importance of a maintaining a healthy internal ecosystem. Some researchers believe the definition of the microbiome should be broadened to include helminthic symbionts along with probiotic microorganisms (Belcaid Y, et al., Cell, 2014, 121-141).

Ancient Symbionts

Parker believes biome depletion and lack of internal biodiversity top the list of causative influences in  American chronic disease. Since “ancient symbionts” can stimulate the TH2 response and decrease pro-inflammatory activity, it is reasonable to consider restocking our biomes with friendly filariae.

American chronic disease. Since “ancient symbionts” can stimulate the TH2 response and decrease pro-inflammatory activity, it is reasonable to consider restocking our biomes with friendly filariae.

Simply said, he believes we should put back the critters that were there in the first place.

“The primary factor associated with allergic and autoimmune disease is apparently loss of species diversity from the ecosystem of the human body, the human biome.” The absence of indwelling eukaryotic organisms “leaves the immune system in a hypersensitive state that, when combined with environmental triggers and genetic predisposition, leads to allergic and autoimmune disease,” Parker says.

Researchers—and people with severe chronic disease—are experimenting with a number of different worms, including porcine whipworms (Trichuris suis ova (TSO)), human hookworms (Necator americanus), human whipworms (Truchuris trichura ova), and rat tapeworms (Hymenolepsis diminuta cysticercoids).

In animal experiments, these organisms have been effective in attenuating autoimmune diseases like Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Crohn’s disease, Ulcerative Colitis and others (Cheng A, et al., Journal of Evolutionary Medicine, 2015, 1-22).

Human clinical studies are limited and show variable outcomes.

A 2017 paper by Parker’s group documents the experience of five physicians monitoring more than 700 people self-treating with helminths for allergies, autoimmune conditions, and cognitive disorders. More than half (57%) had autism. The authors note that, “the majority of patients with autism and inflammation-associated co-morbidities responded favourably to therapy” (J.Liu, et al., Journal of Helminthology, 2016, 1-11). Liu’s findings are anecdotes, not experimental data. But they are suggestive.

In 2007, Argentinian researchers Jorge Correale and Mauricio Farez, published a prospective, double-cohort study assessing whether parasitic infections could alter immune reactivity in multiple sclerosis patients. They monitored 12 MS patients for more than 4 years, measuring a host of immune system markers including: interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, IL-12, transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta, and interferon-gamma.

They found that parasite-infected patients showed a significantly lower number of MS exacerbations, as well as fewer MRI changes when compared with uninfected MS patients (Correale J, Farez M, Annals of Neurology, 2007, 97-108).

While these findings in no way prove that intentional ingestion of worms attenuates MS, it does corroborate the notion that helminths down-regulate inflammation in potentially beneficial ways.

In her review, Helmsby points to safety studies of whipworms to treat ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease. The treatment was well tolerated and produced “significant disease remission.” A subsequent placebo controlled study of 54 UC patients also showed major symptom improvement among worm-treated patients, though remission rates were no different between the two groups (Summers RW, Gastroenterology. 2005: 128(4): 825-32).

In the last decade, six prospective trials have been launched worldwide looking at whipworm therapy for Crohn’s/UC. Two were cancelled for lack of efficacy on initial evaluation. Others are ongoing.

Reflecting on the overall state of research on worm-based therapies, Helmsby says:

“Without doubt there is overwhelming evidence from animal studies that helminth infections exert strong immunomodulatory activity and are able to inhibit, alter and modify other ongoing immune responses. In addition, human cross-sectional studies have established that many chronic helminth infections…may act to inhibit inflammatory responses such as autoimmune and allergic reactions. However, to translate this into clinical helminth therapy forms have proved less successful.”

She surmised that worm exposure might be most beneficial early in life, before the onset of inflammatory disease. Use of helminths to treat long-standing disease may be inherently limited. That said, she emphasized that, “some promising data have been achieved using human helminth therapy.”

Desperation’s a Driver

Proponents of worm-based treatments are not discouraged by the lack of definitive data, the absence of the FDA’s approval, or the generally negative attitude of mainstream physicians. An estimated 7,000 people across the globe that have chosen the controversial crawlers to combat their ailments, often going to great lengths and travelling outside of the US to procure them.

Liu’s collection of personal accounts from 700 self-treating patients and 5 board-certified MDs indicates that people are using worms to treat rhinitis, conjunctivitis, skin conditions, food allergies, type-1diabetes, Crohn’s, ulcerative colitis, asthma, autism, migraines, major depression, and severe anxiety.

What makes a person try an experimental procedure like this? Some self-treaters are scientists or medical professionals. Others reveal desperation as the prime factor.

A number of self-treaters expressed their exhaustive attempts to obtain relief via conventional modalities. Misdiagnoses, unwanted side effects, additional diagnoses, and rising prescription costs all contributed to their decisions to look elsewhere.

A number of self-treaters expressed their exhaustive attempts to obtain relief via conventional modalities. Misdiagnoses, unwanted side effects, additional diagnoses, and rising prescription costs all contributed to their decisions to look elsewhere.

Of the four main types of non-pathogenic worms in current use, the two most popular are H. diminuta and T. suis. Obtaining the worms takes some doing. There are roughly a dozen companies providing them. Given the FDA’s dim view on helminth therapy, all operate outside the US.

One UK-based company, Biome Restoration Ltd, has recently made forays into the field of functional medicine, hoping to engage open-minded clinicians treating patients with complex chronic disorders.

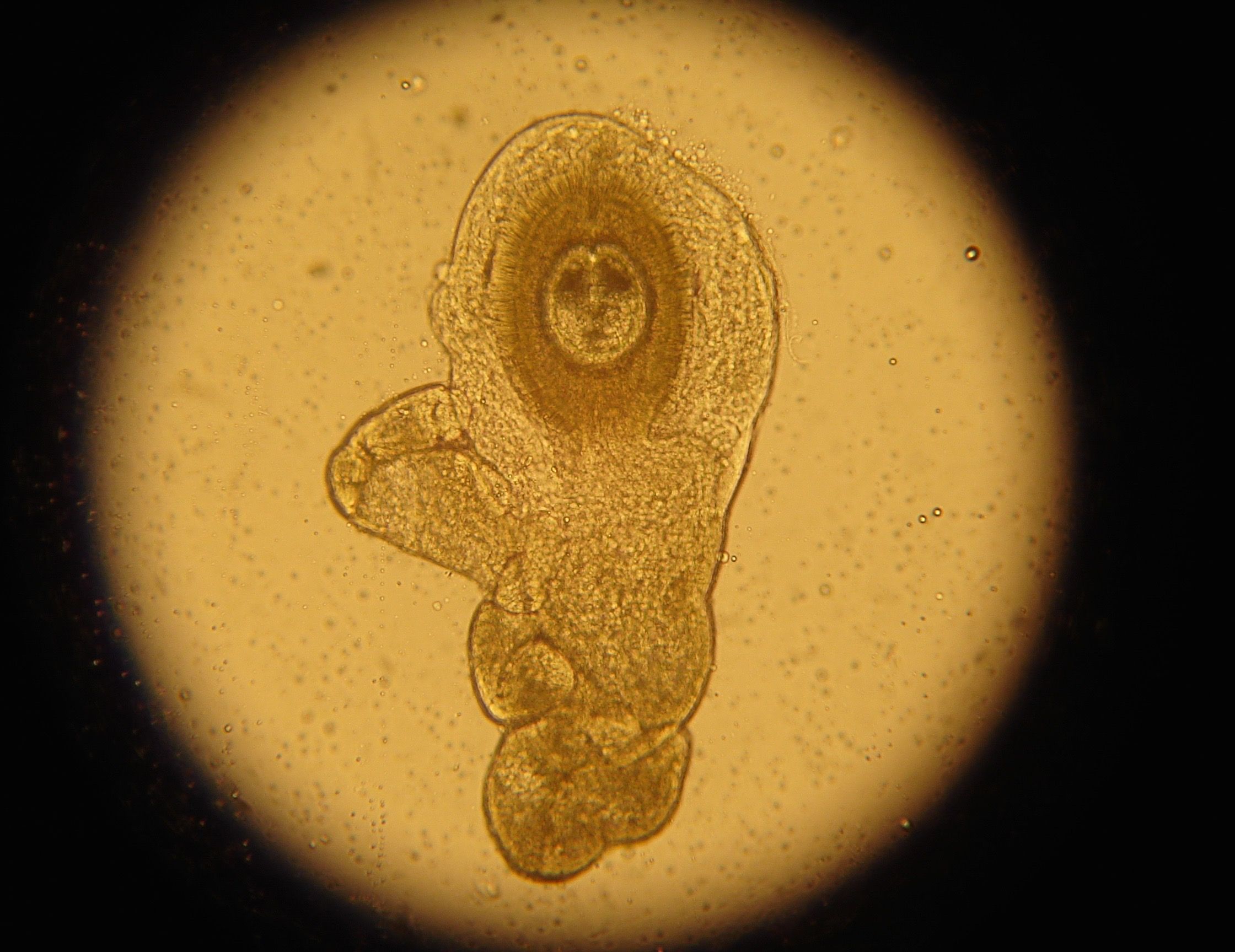

Biome Restoration specializes in Hymenolepsis diminuta cysticercoid (HDC), a rodent tapeworm that is non-pathogenic in humans. It begins its lifecycle in grain beetles. Ancient humans unwittingly consumed these beetles—and the Hymenolopsis eggs—when eating grain-based foods.

In most cases, people take the microscopic helminths orally, in solutions shipped by the companies that produce them. That said, transdermal delivery is also possible for some worms. Dosing is very much an open question, given the limited amount of research available.

Worm n’ Fuzzy

What’s the right worm for a given clinical “job”? Selection is dependent upon:

- condition being treated

- quantity & frequency of dosage

- route of administration (oral vs transdermal)

- potential to colonize in humans

- possible adverse side effects

- cost

- availability

- quality control and harvesting techniques

- loyalty to/quality of the supplier

Duke’s Dr. Parker believes clinicians need to think outside the box about helminths in human health. Just as the conventional view of bacteria shifted in light of modern microbiome research, so might its perspective on worms as we learn more about their role in the internal ecosystem.

Neither he nor any other serious helminth researcher believes worms are cure-all. Ideally, like probiotics, they would play a part in a comprehensive gut health strategy that includes:

- a whole foods diet with prebiotic & probiotic rich foods

- an optimal vitamin D level (40-70mg/dL)

- adequate sleep

- reducing stress

- maintaining a healthy body weight

- decreasing use of antibiotics, acetaminophen, and artificial sweeteners

- eliminating toxic personal hygiene products and antibacterial items (i.e. soaps, sanitizers, cleaners, etc.)

The notion of intentionally ingesting helminths might not leave you feeling exactly “worm and fuzzy.” But remember, it wasn’t long ago that most of us were sticking our noses up at the idea of adding “good bacteria” to our food and drink. Twenty years ago, who would have believed that fecal implants could fight Clostridium difficile?

Today, you can walk into any grocery and buy yogurt, kombucha, lacto-fermented pickles…all teaming with little critters.

As Zaccone and colleagues put it in their 2006 paper, “In some not too distant futurity, there may come a day when we all take ‘helminth supplements’ along with our Omega 3 fatty acids, vitamins, and whatever else goes to make up a modern balanced diet (Zaccone, et al., Parasite Immunology, 2006,515).”

Who’s to say that some day soon, “good worms” won’t be found in grocery aisles near you?

END

Megan Copeland holds a Master’s degree in Clinical Nutrition and Integrative Health. She is a licensed Certified Nutrition Specialist (CNS) who enjoys teaching others about the life changing benefits of whole food nutrition.