A spate of warning letters issued by the Food and Drug Administration offers a clear indication that the agency wants to limit the availability of N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) in dietary supplement products.

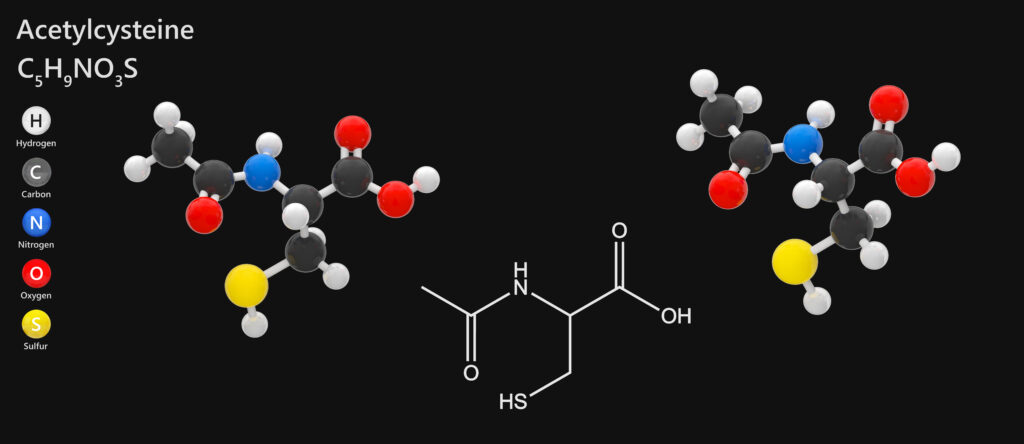

NAC, a precursor to the key antioxidant glutathione, is widely recommended by functional medicine and naturopathic practitioners. It is a common component in many liver support, detoxification, and longevity protocols.

Of the three amino acids needed to form glutathione (cysteine, glycine, and glutamic acid), cysteine is the rate-limiting factor (Minich D. Brown B. Nutrients. 2019). Oral NAC supplementation is an effective way to boost cysteine levels.

There are more than 1,500 supplement products containing NAC listed in the National Institutes of Health’s Dietary Supplement Label Database. And, according to the Council for Responsible Nutrition, there are roughly 150 structure/function claims for NAC-based products filed with the FDA.

NAC supplements have been on the market for decades, and none of these claims have drawn prior objections from the agency.

The Exclusion Provision

Beginning in July 2020, the FDA began issuing warning letters to companies marketing NAC products as hangover cures.

The notion that NAC can mitigate the ill effects of knocking back one too many is questionable, and on face value the FDA’s actions were reasonable.

But the warning letters contained language showing that FDA has a wider intention:

“FDA has concluded that NAC products are excluded from the dietary supplement definition under section 201(ff)(3)(B)(i) of the Act [21 U.S.C. § 321(ff)(3)(B)(i)]. Under this provision, if an article (such as NAC) has been approved as a new drug under section 505 of the Act [21 U.S.C. § 355], then products containing that article are outside the definition of a dietary supplement, unless before such approval that article was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food. NAC was approved as a new drug under section 505 of the Act [21 U.S.C. § 355] on September 14, 1963. FDA is not aware of any evidence that NAC was marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food prior to that date.”

In other words, the agency is reverting to a position that NAC is a pharmaceutical ingredient, based on an approval nearly 60 years ago. This is despite the fact that FDA and other regulators have tacitly permitted its use in supplements for 5 decades.

The impact of the FDA’s move was greatly amplified in May, when Amazon announced its intention to eliminate all NAC-containing supplements from its digital shelves.

Intravenous and oral NAC drugs are used in hospitals to reduce liver damage caused by excessive paracetamol (acetaminophen) intake. It is also useful as a mucolytic in the treatment of obstructive lung disease–the indication for which it was initially approved–and in the context of tracheotomy care. It has not proven effective for treatment of cystic fibrosis.

Most of the original branded pharmaceutical NAC products approved by the FDA were discontinued many years ago, though several companies still make generic versions.

To challenge the sale of NAC in supplements, the FDA invoked the Drug Exclusion Provision within the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which states that a dietary supplement cannot contain:

- an article approved as a new drug

- an article authorized for investigation as a new drug, antibiotic, or biological for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted, and for which the existence of such investigations has been made public, which was not before such approval, certification, licensing, or authorization marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food, unless the Secretary, in the Secretary’s discretion, has issued a regulation, after notice and comment, finding that the article would be lawful under this chapter.

In and of itself, the FDA’s barrage of warning letters is a limited action. The warnings targeted brands making alcohol-related claims, not practitioner-facing companies selling NAC in a clinical context.

Further, there are not (yet) any federal rules that criminalize the sale or purchase of NAC-based supplements.

But the impact of the FDA’s move was greatly amplified in May, when Amazon announced its intention to eliminate all NAC-containing supplements from its online shelves.

Amazon’s Purge

Amazon has been in the hot seat for much of the last year, particularly for its role in promoting COVID treatments that federal agencies deem questionable or fraudulent. The company is eager to appease regulators and avoid large scale enforcement actions, hence its reinforcement of FDA’s view that NAC is a drug.

In a statement about the NAC purge, Amazon stated that, “Third-party sellers are independent businesses and are required to follow all applicable laws, regulations and Amazon policies…..We have proactive measures in place to prevent prohibited products from being listed and we continuously monitor our store.”

Given that Amazon sales represent between 40% and 60% of total annual revenue for many supplement brands, its deletion of all NAC products will likely have serious fiscal consequences.

Further, Amazon owns Whole Foods Market, another major channel for supplement sales. The company has not announced any plan to nix NAC from all Whole Foods stores, but that is certainly a real possibility.

As of this date, NAC products are still available for purchase on Amazon. But some supplement industry executives say their NAC products have already been dropped.

Why Now?

The FDA is well within its jurisdiction to argue that NAC is an approved drug and therefore should not be sold as a supplement.

But the move has many people within the supplement industry asking, Why? And why now?”

It does seem strange that an agency which still does not have a confirmed commissioner would choose to take action in the middle of a global pandemic, to limit consumer access to a harmless amino acid compound and antioxidant precursor.

“FDA has had ample opportunity to raise this issue in the past and yet has never done so,” writes attorney Stan Soper, one of a number of nutrition-focused lawyers alarmed by the agency’s insistence on drug-only status for NAC .

Some in the supplement field see this as part of a broader federal crackdown on non-pharma approaches to managing COVID.

“FDA has had ample opportunity to raise this issue in the past and yet has never done so.”

–Stan Soper, Attorney

Many functional medicine physicians recommend NAC as part of their comprehensive nutrition-based protocols for mitigating the effects of SARS-CoV-2.

The Institute for Functional Medicine’s COVID-19 Task Force included NAC in its COVID treatment guidelines, noting that while there are no definitive clinical studies showing that NAC will reduce COVID symptoms or improve outcomes, there are studies showing it can reduce episodes of influenza, and flu-related symptoms among elderly people.

From the outset of the pandemic, the FDA and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) have been consistent in their stance that there are no approved drugs to treat COVID, and certainly no supplements for which antiviral claims can be made. The agencies have jointly issued hundreds if not thousands of warning letters to supplement companies, as well as to practitioners making COVID-related claims.

Emerging New Drugs

There are now 17 clinical studies of NAC in the context of COVID care listed in the government’s Clinical Trials registry. This includes a high-profile study now underway at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center involving 84 high-risk patients with COVID, treated with inhaled or intravenous pharmaceutical forms of NAC.

Others, like a 64-patient COVID study at Baylor College of Medicine, are using NAC supplements.

Last year, a pharmaceutical company called Orpheris ran a phase 1 open-label clinical study of subcutaneous injections of “OP-101,” which is Dendrimer N-acetyl cysteine. The study looked at pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and adverse effects in 8 healthy volunteers. The data were initially posted to the clinicaltrials.gov website in March 2020.

Orpheris is a subsidiary of Ashvattha Therapeutics, a Redwood City, CA drug development company focused on “harnessing the power of Hydroxyl Dendrimers (HDs) to create a new class of Disease Cell-targeted Precision Medicine.”

The company’s long-term vision for OP-101 is to develop it as a treatment for childhood cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (ccALD). According to Orpheris’ website, researchers “will assess the ability of OP-101 to restore microglia to a normal state, using neural imaging techniques.”

Beyond ccALD, a rare X-linked disorder that causes abnormal fatty deposits in the brain, Orpheris has plans to “investigate the potential of OP-101 in other neurological diseases,” particularly Parkinson’s and aymyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

This is not the first time FDA has invoked the Drug Exclusion Provision to retroactively eliminate specific ingredients from the supplement sector. Over the years, it has taken similar action—to varying degrees of success–against vinpocetine, red yeast rice, vitamin B6 (pyridoxamine), and CBD.

Some supplement industry leaders believe it is not a coincidence that the FDA is squelching the sale of NAC supplements at the same time as several drug companies are developing new patentable prescription forms of the compound.

Casting a Shadow

In an interview with Natural Products Insider, Council for Responsible Nutrition president Steve Mister contended that the FDA is attempting to “cast a shadow on NAC as a dietary supplement, which would encourage the drug companies to go forward under the thought that they could get a monopoly on the ingredient if it pans out.”

This is not the first time FDA has invoked the Drug Exclusion Provision to retroactively eliminate specific ingredients from the supplement sector. Over the years, it has taken similar action—to varying degrees of success–against vinpocetine, red yeast rice, vitamin B6 (pyridoxamine), and CBD.

Mister argues that the agency is misusing the Provision which, he says, “was intended to create a race to market so that you didn’t take away the incentives for drug companies to study products for potential disease uses. But it was never meant to be a shield to just go out and start removing (supplement) products from the market.”

He sees it as evidence of a deep-seated bias within FDA that favors pharma, “which makes sense because FDA has a lot more control over bringing a drug to market than they do foods or cosmetics or supplements.”

Predictably, FDA officials have dismissed this and other similar allegations.

NAC Still Legal

For the moment, it is still legal for companies to sell products containing NAC, for practitioners to recommend them, and for consumers to buy them. But if Amazon follows through with its purge, they could become more difficult to obtain.

Industry trade groups are rallying to urge FDA to reconsider its position on NAC.

On his blog, attorney Stan Soper states: “I’m sure you will shortly hear objections from the major trade associations, who are likely to work with industry to try to find evidence that NAC was part of the supplement or food supply prior to 1963 or find some other basis to challenge FDA’s position. It remains to be seen whether FDA will exercise enforcement discretion and allow NAC to remain on the market as a supplement or will otherwise back down from this new aggressive posture.”

Regardless of how the NAC issue ultimately resolves, it is clear that even without a commissioner, the agency is increasing its scrutiny of the supplement sector.

Crackdown on Fertility Claims

At the end of May, the FDA and FTC began a joint crackdown on supplement claims related to fertility and treatment of infertility. The agencies issued warning letters to five companies marketing nutritional or herbal formulas that purport to improve fertility or mitigate amenorrhea, endometriosis, luteal phase defects, polycystic ovary syndrome, or to prevent miscarriage.

The agencies view infertility as a disease state, which means that supplement companies cannot legally make claims related to it.

Further, the warning letters contend that infertility is “not amenable to self-diagnosis or treatment without the supervision of a licensed medical practitioner.”

END