For the past decade, Dr. Decker Weiss has been splitting his time between his home base in Carefree, AZ, and makeshift emergency clinics on the borders of Hell.

Weiss, a naturopathic physician (Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine ’97) with advanced training in cardiology, has undertaken multiple medical missions to refugee camps, disaster sites, and regions of conflict across the globe.

Through his independent non-profit organization, Global Medical (formerly Peace Possible), he has provided holistic medical care to refugees and marginalized people in

Iraq, Jordan, Gaza, Israel, and Lebanon, Rwanda, Senegal, and Haiti/Dominican Republic.

Weiss recently returned home from a caregiving mission to Przemyśl (pronounced “Pshemishle”), an ancient Polish city on the San river, situated just a few miles from Poland’s border with Ukraine.

There’s a highway running directly between Przemyśl and Lviv, Ukraine, roughly 60 miles to the east. Since February, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have taken that road, fleeing the Russian invasion of their country. Global Medical is among dozens of international organizations that have set up clinics, relief stations, and canteens on the outskirts of key towns along the Poland-Ukraine border, to help the refugees as they pour into Poland.

In addition to providing care for refugees, Weiss and his colleagues are studying the neurophysiological changes that occur in people who’ve experienced extreme violence and social upheaval.

War, says Weiss, is chronic inflammation writ large. Intractable conflict—which could easily become the situation in Ukraine–is akin to an autoimmune condition in the human social tissue. Over time, and without relief, victims of violence easily become its perpetrators, perpetuating the cycle of strife. “As inflammation goes up, so does willingness to kill,” says Weiss. “We have correlative data to show this.”

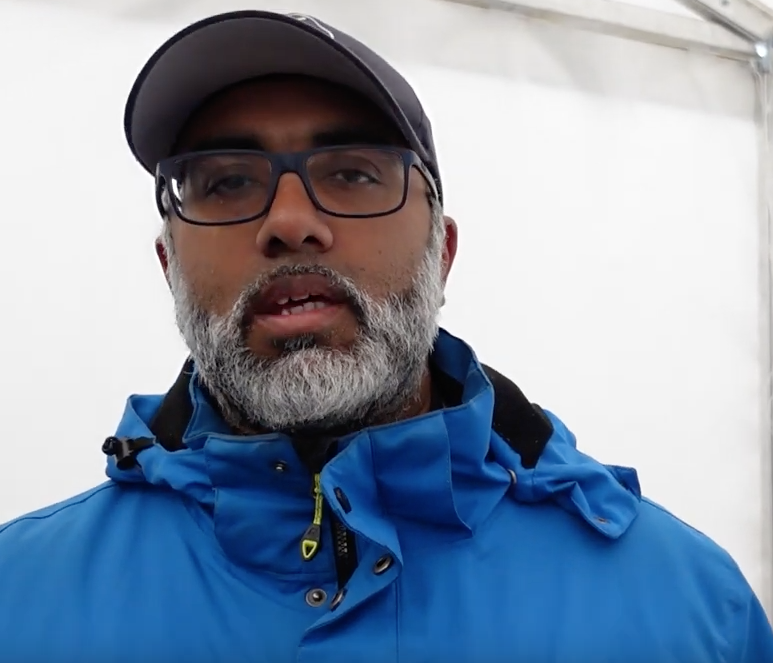

Holistic Primary Care spoke with Dr. Weiss just prior to his departure to Poland, and shortly after he returned from his first journey. Here are highlights of our interviews:

HPC: Tell us about this current mission to the Ukrainian border.

Weiss: We were over there from March 24th through April 1st. First, we pre-supplied five pallets of nutritional supplements, electrolytes, probiotics, and meal replacements which were shipped to Lviv and then turned over to the Ukrainians for distribution. Our biggest partner supplying products is Atrium Innovations.

Then, I had 400 pounds of the latest trauma supplies and holistic COVID-19 treatments that came with me in six bags. Stuff like silver products, quercetin, zinc, vitamin C, and also drugs like prednisone. It was a lot of baggage fees! We had pre-selected a border area between Medyka, Poland and Shehyni, Ukraine, as the place to set up due to its low likelihood of being bombed, and the high number of refugees pouring through there.

HPC: What are your working conditions like over there?

Weiss: We partnered with a heavily-resourced group called Humanity First out of Germany. We—Global Medical and Humanity First–were the second group to arrive. Rescuers Without Borders, an Israeli organization, was first. One week after I arrived, the International Red Cross started to set up. Doctors Without Borders is also there, supplying more surgeons closer to the fronts in Lviv, Dnipro, Kharkiv, and Kiev.

After several meetings with the Humanity First team, their chairman, Muhammad Zubair, named me the “Chief” and we set up two clinics. The clinic on the Poland side has an initial triage and quick-treat area, a four-bed clinic, a one-bed Cardiac Care Unit, and a one-bed Intensive Care Unit. We were working in freezing temperatures with sleeting rain, which made it difficult, but it came out beautifully. We supplied all of this from their donations and my supplies, making it the best equipped and well-stocked clinic in the area.

We are currently seeing 90-150 refugees a day there. Due to our success, the chairman asked me to set up a smaller version on the Ukraine side of the passport control station. After some political work with the Ukrainians, our team set the clinic up in less than four hours, and started seeing patients.

There are all kinds of wonderful people who’ve taken it on themselves to show up and help in whatever ways they can. My support team included a whiskey maker from Ireland, and two members of the East Anglia, UK, chapter of the Bearded Villains—an international fraternity of heavily bearded men dedicated to family values, loyalty, and charity. They worked hard, in terrible weather, and they never complained.

After the initial setup, we rolled out two fully stocked integrative clinics which utilized advanced holistic COVID-19 treatments, acute homeopathy, and probiotics after antibiotics. Pretty good work for 10 days! This was my most successful deployment to date. I not only provided care but used my administrative experience to set up two full clinics. It feels good to know that what Global Medical and Humanity First put together will sustain until it is no longer needed.

HPC: What did you see among the Ukrainian refugees?

Weiss: We saw two types: there were folks who looked like they were flying off to Paris for the weekend. Perfect hair and make-up, high end luggage. While sad, they were also hopeful that this would end soon and they would return home. These people were generally from the western part of Ukraine.

And then there were folks who were dirty, their clothes ragged and beat-up, and they had an energy of dread and sadness about them. These people were from the Central and Eastern regions of Ukraine, the areas most affected by the war. They had no illusions.

Medically, we were treating a lot of conditions related to exposure to elements–issues such as frostbite, and hypothermia. The weather when I was there was still pretty harsh. It was cold and damp, sleet and rain, near freezing almost every day. Some of the refugees had been travelling for days or weeks.

We were distributing emergency blankets and ponchos, wrapping the young ones up to keep them warm. The Israeli team was building plastic covered shelters to keep the refugees sheltered from the elements. That was really important, because in situations like this cold exposure quickly becomes catastrophic. The medical problems increase exponentially. Eventually, with financial support from Tom Shiflet who runs The Great Need, and actor Hugh Grant, we were able to build a covered walkway across the border with propane heaters.

We also treated a lot of people for headaches and hypertension, and of course some wound care. I treated several people that cut themselves on shrapnel and who had some wounds that were originally treated at their local hospitals but needed follow-up care in our clinic. I also treated a patient who had a burn caused by a banned thermobaric weapon. It was awful.

But the hardest thing for me to see was watching men drop their loved ones off at the border, and then turning around to go off to fight. Watching those goodbyes, which really may be goodbye forever, was very hard. For the refugees with family members fighting, each day is full of fear, waiting to hear if their loved ones are still alive.

One thing that was very notable…the Ukrainians love dogs and cats! So quite often the refugees fled with their pets. The tent across from one of our clinics offered free veterinary service, which was pretty cool.

HPC: What was the Covid situation among the refugees and in the area where you were encamped?

Weiss: The Covid-19 rate was low, thank heavens. In general, the Ukrainians had done a good job of containing the virus prior to the war. But we are preparing now to have a comprehensive holistic Covid response in the Fall. It could get really bad.

HPC: What initially prompted you to get involved in providing care for refugees and displaced people?

Weiss: During my work as a cardiologist, I started to dive deep into neurotransmitters and the neurohormonal aspects of cardiology, and of pathology in general. Through this work I took a large deviation in my career to study the relationships between inflammation and neuro-imbalances at the individual level, and the underlying mechanisms causing intractable cycles of violence, poverty, and radicalization on the societal level.

These interests led me to a partnership with Artis International, a global interdisciplinary research organization that studies the dynamics of violence and conflict, with an eye toward conflict resolution. Artis researchers have worked in war zones all over the world. One of the constant issues in these places is the radicalization of refugees, which perpetuates the cycles of violence. Artis initially brought me in as a physician, and from there I spun out to my own NGO now called Global Medical. We have run clinics and done studies in conflict and poverty zones around the world including Iraq, DR/Haiti, Thailand, Gaza, Viet Nam, and Senegal to name a few.

As the Ukraine invasion developed, it became clear that it may not just be a war zone, but it could become another area of intractable conflict.

HPC: How does the situation of the Ukrainian refugees compare with what you saw when you worked among the Yazidis in Iraq, or earthquake refugees in Haiti, or in the other places you’ve been with Global Medical?

Weiss: While there are some similarities, there are four major differences from my viewpoint. The first is support from the Western world. Between the NGO’s such as World Central Kitchen, and all the others being there for the Ukrainians practically from day one, and all the weapons and supplies being shipped in from NATO countries, the Ukrainians, though they are under attack, do not feel totally isolated.

Every day, there were 40-50 vetted soldiers from other countries with papers crossing into Ukraine to fight. This included Americans. We also saw munitions going in daily, as well as food and medical supplies.

Secondly, we’re seeing the unity of an entire country pulling in one direction, instead of factionalized groups pushing private agendas and fighting with each other. This is impressive. The Ukrainians are showing a remarkable degree of unity in resisting the Russian invasion. This is very different from other places where I’ve worked.

Thirdly, Poland. From the very beginning, Poland set the tone by saying to the Ukrainians that they have refuge in Poland for as long as they need it. Other countries followed suit. I was at a meeting where we lobbied for Hamburg to increase their quota to 1,000 Ukrainian families residing temporarily in Poland. Not only did the agree but they upped it to 1,500 families. This would not have happened without the Poles being who they are–kind, hardworking, and inspirational.

Moldova, Slovakia, Romania, Hungary…they’re also taking in a lot of the refugees. The people in border towns, they’re sacrificing much to help strangers. It’s a phenomenal story of people helping people. Sure, there are weaknesses and problems—we’re seeing racist diatribes. And we’ve seen the reports of African-Ukrainians being treated very badly. But on the whole, I’ve never seen a boots-on-the-ground refugee effort go this smoothly in my life.

Fourth, there’s President Zelenskyy. Somehow a comedian who was in a show about a comedian who becomes president, actually became president! None of this qualified him to lead a country in a time of war. And yet, he is doing just that. The whole region recognizes his leadership as the driver for winning the war. If the Ukrainians do win this war or at least come to an acceptable peace, there will be statues of him not only in Ukraine, but throughout the world as a symbol of freedom. Keeping Kiev and forcing the Russians out of the northern part of Ukraine was a major shot in the arm for the Ukrainians.

HPC: Why do you think the western countries have been so much more welcoming to the Ukrainians than, say, to refugees from the Middle East or North Africa?

Weiss: A lot of it comes down to, “Do they look like us?” If they look like you, you tend to support them. Wealthy Western countries will do more for people who look like them, who share their culture.

Also, the Ukrainian refugees are coming into the Polish border towns and then dispersing. Many of them have family in other countries. They’re not getting stuck in refugee camps like in Lebanon or in Greece. Those intractable refugee camp situations are very bad news.

HPC: Based on your experiences, and your understanding of “social inflammation” what’s likely to happen over there?

Weiss: Social inflammation is when a society loses its rationality to a mass inflammatory process, and people become willing to do things as a group they never thought they would or could do. It is important to understand that while hope can be a powerful force, hopelessness is also a very powerful force. If I don’t care about my life…that’s a powerful tool. People who no longer care about life can do horrific things.

At Global Medical we have a three-part mission: 1) Diagnosing, 2) Treating, and 3) Reversing. It is my hope that through study and holistic treatment, we can reverse the cycle of violence and prevent the catastrophic effects of social inflammation such as group hate and intractable violence which leads to chronic cycles of poverty, hopelessness, and more violence.

In the eastern part of Ukraine, that cycle is already starting. So, we have our work cut out for us when we return later this summer.

HPC: Based on what you have learned so far, how do you see the situation playing out over the long term?

Weiss: Without any data, my guess is that Russia will leave Ukraine in ruins, like they left Chechnya in the 90s, and Afghanistan in the ‘70s.

The Russians are already losing a lot of hardware, and soldiers at an alarming rate. Vehicles, tanks, planes. This frustrates them. So, they’re going to bomb more. They’re using cluster bombs, and thermobaric weapons. Cluster bombs are not expensive, and easy to deliver. The goal is breaking morale. But that doesn’t work well.

One possible outcome is that Putin gets tired, steps back, and slowly pulls out but holds onto Donbas and Luhansk, and the other breakaway regions in the east.

Or Putin could continue his quest to dominate Ukraine and it becomes a long, awful, protracted slog. A lot of the Ukrainians envision a Ukraine without Russia’s influence, and they are willing to fight and die for that vision.

And if Russia does end up taking Ukraine, how long will Russia be able to hold it? Yes, they can topple the government and put their own people in. But look at what happened in Afghanistan for the Russians, and also for us in that same country. Look at Iraq. You can put your people in, but that doesn’t make it a functioning country. And eventually there’s enough death and misery that you’ll leave. And of course, it is the ordinary people who lose.

This could also still become a real war between NATO and Russia, with the possibility of nuclear war. It is not out of the question. The West, and the US, has been tested. Will we be isolationist? Will we support NATO? Putin is going to test that, and test that, and test that.

HPC: What’s next for you and for Global Medical?

Weiss: We will return in July to not only run and expand our clinics, but also to run a study to see if the Ukrainians are radicalizing against the Russians. Will they be willing to do suicide bombings? Have their “sacred values”—their unwillingness to make a moral trade-off for material gain–changed? Are they still willing to die for their land? Have they become hopeless and hardened?

We will run our study and report our data to the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict (CRIC) at Oxford University and submit it for publication. The goal is to understand where the Ukrainians are so we can form the right policies to support them. We are looking at actionable items as far as long-term care, long term support to reverse the sequelae of trauma.

HPC: Based on your research, what would you say is the difference between, say a Ukrainian patriot—or any other soldier–who is willing to kill and die for a cause, and someone who has become “radicalized”?

Weiss: Radicalization seems to set in over a period of time as people grow to hate others due to the chronic violation of what we call their Sacred Values. This is a term Artis International’s co-founder, Scott Atran, defines as principles or people that someone will not abandon under any circumstance, and for which they are willing to die—or kill. These may be different for different people, and they may not even be conscious.

For some, sacred values center on a sense of “home” or family honor, or a religious or ethnic group. Sometimes it is a political or social ideal. These are the values that a person “refuses to sell. Activation of emotions around a person’s sacred values happens in specific brain loci, and this is true regardless of what the particular values may be.

Medically, this is a process of losing protective mechanisms and clear thoughts as inflammation damages the CNS and neurotransmitter activity. Radicalization happens when people live for long periods in toxic conditions, with poor nutrition, repeatedly have their sacred values violated, and they see no hope for themselves other than through violence. So, violence becomes the only hope.

These changes can affect the way genes are expressed, and are passed to the children as well. We call it “Trans-Generational Genomic Expression” (TGGE). This is what we think is causing the multi-generational cycles of violence.

HPC: You’ve started another interesting project called Red Equal. Tell us about that.

Weiss: This is a student loan debt resolution program for medical graduates, connected to Global Medical’s field clinic operations. Let’s say you graduate from Harvard Medical School, or Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, or wherever, and you’re in debt. So, you go work in Senegal for 2 years and your debts are paid off. We provide training in global medical systems and in providing care for people in conflict zones and regions of poverty. We call it Red Equal because everybody—no matter what country or religion, no matter if you’re rich or poor—everybody has red blood. It’s a great equalizer.

HPC: How do you find the strength to provide care in such difficult and often heartbreaking situations?

Weiss: The truth is, I feel really good when I do this work, when I see a line of refugees and I know I can help them. In cardiology, I get to do what I like to do about half the time, which is pretty good. With Global Medical, I get to do what I love to do all the time. In one sense, it is purely selfish! Yes, my wife and I have a nice life in Carefree, Arizona, and I like to put a vinyl record on the stereo and relax and enjoy. But our dream retirement is to open an orphanage for refugee children. If, in 20 years from now, I can say I helped lots and lots of people and I enjoyed doing it, that’ll feel very good.

One last note: I would like to thank the Italian pianist, Davide Martello, who played for us each day on his “off-road” grand piano. He was out there all the time, bogged down in mud, playing beautiful music for the Ukrainian refugees boarding buses to their new homes. He created something beautiful for all of us on days that were cold and damp both in weather and in spirit. He is the definition of what I consider to be a healer.

–END–