Discussions about the microbiome in human health usually focus on the gut. But what about the microorganisms that reside in other parts of the body––like the vagina? The vaginal microbiome is a critical, yet largely overlooked, aspect of women’s health.

That’s in part because scientists know far more about the microbes in the digestive tract than those in the vagina. Then there are cultural factors like taboos surrounding female genitalia and sexuality that limit open, honest conversations about vaginal symptoms.

Yet some of the most common complaints women bring to their doctors are directly or indirectly related to imbalances in the vaginal flora. Many vaginal symptoms are treatable with natural therapies that rebalance the microbiome and heal symptoms just as effectively, if not more so, than conventional antibiotic or antifungal drugs.

Vaginal Dysbiosis Ups Infection Risk

Though the gastrointestinal microbiome still dominates in research circles, scientific interest in the vaginal microbiome is growing.

Recently, Virginia Commowealth University launched a major research initiative called the Vaginal Microbiome Consortium, to foster cross-disciplinary studies on the vaginal flora and how it influences women’s health, sexuality, fertility, and infant health and well-being.

The vaginal microbiota consists primarily of bacteria, yeast, and fungi. As is the case with the gut microbiome, each individual’s vaginal ecosystem is unique, and influenced by a host of factors: age, diet, environment, hormones, and genetics. The quantity and diversity of microbes in the vagina “have significant implications for a woman’s overall health,” said Liisa Lehtoranta, PhD, manager of research and development in the Global Health & Nutrition Science division at DuPont Nutrition & Biosciences.

Lehtoranta, who specializes in research on probiotic bacteria, explained that in healthy women, the vaginal microbiome is usually highly populated by a few species from the Lactobacillus genus. “As a key feature, vaginal lactobacilli produce lactic acid, which creates an acidic [low pH] microenvironment and prevents the overgrowth of potentially harmful bacteria,” she said.

But a host of environmental and lifestyle factors can upset this optimal microbial makeup. Vaginal imbalance or dysbiosis, Lehtoranta said, is a known risk factor for yeast infections and bacterial vaginosis (BV).

“BV is in turn associated with urinary tract infections, increased risk of infertility, fallopian tube inflammation, adverse pregnancy outcomes and preterm birth.”

Vaginal dysbiosis also correlates with sexually transmitted infections like HIV, human papillomaviruses, herpes, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, she added.

Drug-Induced Infections

Vulvovaginal infections account for millions of physician visits annually, ranking among the top conditions for which women in the US seek medical care. Treatment typically involves simple lifestyle modifications plus a course of antibiotics or antifungal drugs.

In the case of a single infection, a standard antibiotic regimen will generally alleviate symptoms. But these powerful pharmaceuticals also disrupt the delicate vaginal microbiome, potentially setting the stage for recurrent future infections that are far harder to clear.

“A classic and unfortunate 3-step sequence of events is often the starting point for people with chronic vaginal infections,” Amy Day, ND, founder and medical director of the Women’s Vitality Center in Berkeley, Calif., told Holistic Primary Care.

The pattern begins when a patient develops a urinary tract infection (UTI) which is treated with antibiotics.

Hard-hitting antibiotics “throw off the vaginal flora due to killing the good bacteria along with the bad ones that are causing the UTI,” Day explained. They may knock out the UTI, but in doing so, they create the perfect environment for fungal pathogens to grow unchecked.

As in the gut, certain microbes in the vagina are “critical for maintaining the balance of good bacteria to help fend off bad bacteria and yeast,” Day said. It is normal and even healthy for small amounts of unwanted bacteria and yeast to appear, provided there are enough beneficial flora also present to prevent pathogenic microbes from causing harm.

Lactobacilli, for instance, keep infectious yeasts like Candida albicans––the main cause of genital yeast infections––from reaching dangerous levels. Antibiotics or other forces that disrupt or destroy the Lactobacilli, create conditions for Candida overgrowth.

Rebalancing After Antibiotics

It is crucial to rebalance the vaginal flora after a course of antibiotics. Otherwise, the very medications intended to treat one infection might just end up causing another.

Day said that in her practice, it is “very common” to find that patients with long histories of chronic vaginal infection experienced their first symptoms following antibiotic treatment.

“If the pharmaceuticals always worked and didn’t have side effects, I probably wouldn’t see any of these patients because they would just get an insurance-covered prescription and be done with it.”

“That works for some people,” she acknowledged. “Diflucan can knock out a yeast infection and a patient can be fine. But it’s a hard-hitting drug and it doesn’t always work, and it often requires re-treatment and re-treatment if you’re not rebalancing” the vaginal flora.

What makes the UTI-antibiotic-yeast infection sequence even worse is that in many cases, it’s preventable.

Teaching women how to support their own healthy vaginal ecosystems can minimize the likelihood of recurrent infections.

“This is definitely an unmet need in the medical field,” Day suggested. Patients with vaginal infections are frequently, “handed a prescription without finding out first what is truly going on and what needs to be treated.” Others receive antibiotics or antifungals that do not effectively clear their symptoms, which sends them “to the internet to try and research what else they can do for themselves. It’s very frustrating.”

Fortunately, “most doctors are now being more cautious about prescribing antibiotics without first confirming the [presence of a] UTI, so that is a step in the right direction,” Day noted.

The Maternal-Infant Microbiome

Conventional medicine does recognize some additional aspects of the vaginal microbiome, particularly in the context of pregnancy and childbirth.

Take Group B Strep (GBS), a prevalent bacterial vaginal infection with potentially serious consequences for newborns. Physicians routinely screen expectant mothers for GBS in the late stages of pregnancy and provide treatment as needed to prevent mother-to-infant transmission.

But beyond that, there is also the broader idea of a shared “maternal infant microbiome” (Dunn, AB et al. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2017; 42(6): 318-325). A baby’s gut flora begins developing in utero, but the birthing process will significantly influence the “initial colonization process of the newborn microbiome.”

During vaginal delivery, infants are inoculated with microbes from the mother’s vagina while passing through the birth canal. Exposure to healthy––or unhealthy––vaginal flora can affect a baby’s health even long after birth. Studies indicate that babies delivered by Caesarean section have distinctly different microbiomes than those delivered vaginally. C-section infants frequently carry higher levels of opportunistic pathogens at birth, as compared to vaginally delivered babies (Shao, Y et al. Nature. 2019; 574: 117–121).

Given that a mother’s vaginal flora directly influences an infant’s gut microbiome, some holistic medical practitioners recommend that expectant patients supplement with high-quality probiotics during the last trimester. Supporting healthy intestinal flora after birth is especially important for babies delivered by C-section.

Hormonal Triggers

Bacteria and yeasts thrive in damp, warm environments, so conditions like high humidity or wet clothing can promote pathogen overgrowth. Diets high in refined carbohydrates provide an ideal fuel source for sugar-loving yeasts, increasing the risk of vaginal dysbiosis.

Hormone fluctuations can also trigger infections. Some patients consistently experience monthly flares in chronic BV or candidiasis at specific points in their menstrual cycles.

Right around mid-cycle, “there’s an estrogen spike that happens as part of the ovulation process,” Day pointed out. Recurrence during ovulation is not uncommon in patients who experience frequent yeast infections. For others, infections arise shortly before the bleeding phase when hormone levels start to drop. Still others notice that symptoms return right after their periods, as menstrual blood both adds moisture and feeds vaginal microorganisms.

Low estrogen later in life can be problematic as well. “In the post-menopausal years, some people experience an increase in UTIs and vaginal infections,” Day said. Declining estrogen in the vaginal mucosa correspond with weaker immune responsiveness, likely resulting from decreased circulation. Treatment with local estrogen therapy can help boost immunity and prevent additional infections.

Medical Red Flags

Some women recognize that their symptoms appear at specific times or under specific conditions, but others do not.

You can help by asking patients to carefully track and document when their infections occur. When evaluating a patient’s flare ups, make sure to ask about dietary habits, clothing choices, menstrual timing, and environmental conditions. Do infections occur predictably at a certain stage of the menstrual cycle, or after certain vacations or certain types of meals?

Taking the time to ask those questions may yield vital insights about a patient’s vaginal microbiome.

In cases where the infection triggers aren’t immediately apparent, dig deeper. Chronic infections of the genital tract––or anywhere else for that matter––are medical red flags for underlying problems.

“Yeast overgrowth in the vagina can occur on its own, but I do think about yeast in the gut in cases where the vaginal yeast infection keeps recurring,” Day noted. “The bowel can act as a reservoir, and even after treating a vaginal yeast infection, any remaining yeast can travel from the anus to the vagina and cause another infection.”

For this reason, Dr. Day says she often pairs local vaginal treatment with systemic oral antimicrobials.

Chronic vaginal infections may also signal a compromised immune system. Always “screen for any signs of recurring infections that may indicate an immune deficiency state.”

Test Thoroughly

When treating vaginal symptoms, try to determine the exact cause of a bacterial or yeast infection and treat accordingly. It will mprove the likelihood of successful eradication, and also reduce risk of recurrence.

Unusual vaginal discharge marked by changes in color, consistency, or smell, as well as redness, swelling, rashes, and itching or irritation of the vagina or vulva, are the typical indicators of vaginal dysbiosis. But “symptoms depend on the infection in question,” Dr. Lehtoranta cautioned.

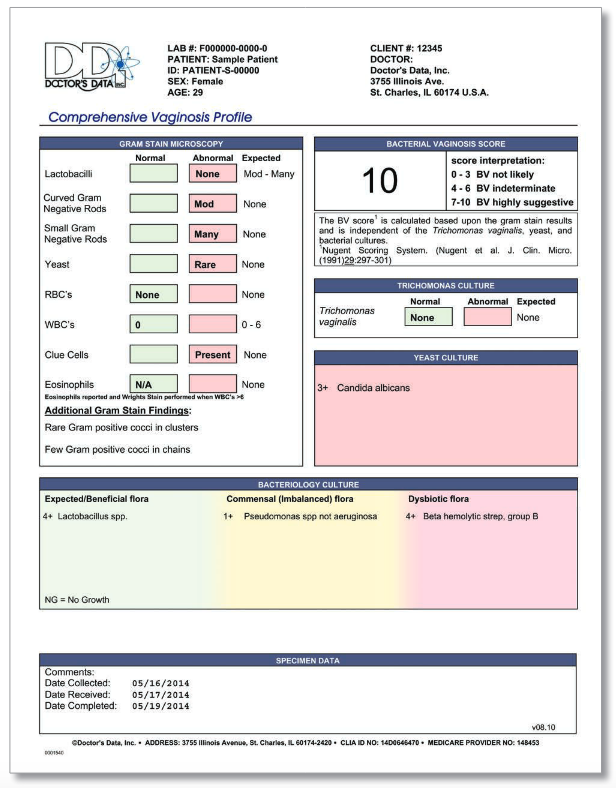

There are a number of different testing options now available–including home test kits—to characterize the vaginal microbiome and determine what type of infection may be present. One example is the Vaginosis Profile by Doctor’s Data, which patients can complete at home and send to a lab for analysis.

Testing is “a fantastic way to get more information, especially in women who struggle with chronic and recurring infections,” Day says. Results may take several days to return, so testing is somewhat less useful in acute cases requiring immediate treatment. But generally, “it’s so useful to know about [a patient’s] levels of good and bad bacteria and yeast…to help guide treatment decisions.”

Natural Alternatives

A host of natural therapies can effectively treat many symptoms of vaginaly dysbiosis without causing harmful side effects.

Begin by encouraging patients to drink more water.

Supplements like d-mannose, vitamin C, probiotics, or herbs such as uva ursi and berberine are great options for patients with UTIs.

For confirmed yeast infections, Day’s go-to treatment is boric acid or Yeast Arrest, a natural vaginal suppository made by Dr. Tori Hudson’s Vitanica supplement line. The product is a homeopathic suppository with a cocoa butter base and supportive natural ingredients including boric acid, tea tree oil, neem oil, Oregon grape root, Lactobacillus probiotics, and homeopathic botanicals, in a base of cocoa butter. “It is highly effective at relieving uncomfortable symptoms and usually clears the infection completely with twice a day use for 7-14 days,” she reported.

Botanical anti-fungal supplements like CandidaStat (Vitanica) or Biocidin (Biobotanical Research) may further benefit patients by providing additional systemic support during infection treatment.

“If the infection is severe enough that antibiotics truly are needed, then the patient should always be given probiotics along with that prescription,” Day urged. Using “high dose probiotic supplements during the course of antibiotics––taken at a different time of day, two hours away from the antibiotic doses––and then for two to four weeks afterwards, can help to maintain the healthy flora and prevent a vaginal yeast infection.”

She added that vaginal probiotics make good sense “no matter what treatment is used to kill off [an] infection.”

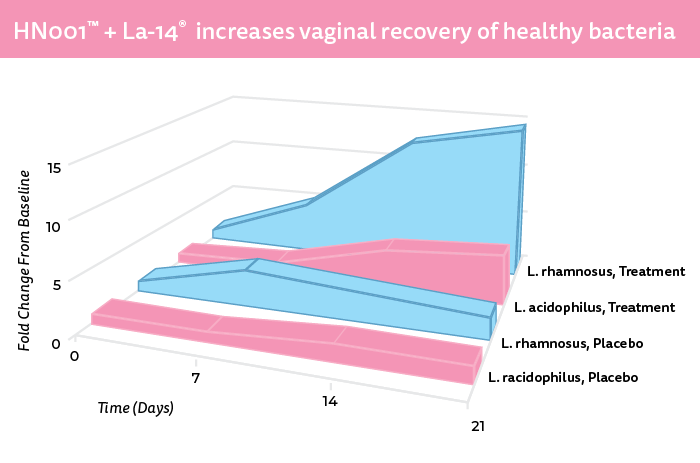

Supplementing with oral probiotics may also help to maintain or increase healthy levels of vaginal lactobacilli. DuPont’s HOWARU® Feminine Health combines Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001™ and Lactobacillus acidophilus La-14®, two bacterial strains offering “beneficial effects in regards to BV and vulvovaginal candidiasis recovery as an adjunct to antibiotic or antifungal therapy, respectively,” Lehtoranta said.

“Unlike antibiotics and antifungal drugs intended for killing harmful bacteria and yeast, which may be harmful to intrinsic vaginal microbiota as well, probiotic strains in HOWARU® Feminine Health are intended for maintaining the good lactobacilli balance in the vaginal tract,” she said. The probiotics in HOWARU® promote lactic acid and hydrogen peroxide production, which lowers pH levels in the vaginal environment.

Jarrow Formulas’ Fem-Dophilus is another widely used vaginal health probiotic that can be swallowed orally or inserted vaginally once a day at bedtime to help restore beneficial flora and prevent infection recurrence.

The Gut-Vagina Axis

In the same way that diet affects the intestinal microbiome, it also affects microbial diversity in the vagina.

Reducing or eliminating carbohydrates, sugars, and alcohol often alleviates vaginal symptoms and prevents them from recurring. Patients with persistent yeast infections may need to follow a strict zero-sugar anti-candida or low-mold diet. Others with less severe or less frequent infections can tolerate modest amounts of sugar or other carbs.

“There are implications that the Westernized diet and high saturated fat content may cause systemic inflammation, which may have an unfavorable effect on the vaginal microbiota composition through the so-called ‘gut-vagina axis,’” Lehtoranta warned.

Equally important as what’s removed from the diet is what stays in it. In addition to plenty of fresh or lightly cooked vegetables, it is wise for women to incease their intake of fermented vegetables, yogurt, or other Lactobacillus-containing foods.

Patients at risk for vaginal infections can further reduce the likelihood of recurrence by wearing underwear made of cotton or other breathable fabrics, and changing out of tight-fitting swim suits or sweaty workout clothing promptly after use.

It is also a good idea to avoid douching and instead wash the vulvovaginal area with water only.

END