Vacations to Thailand aren’t just for the beaches anymore.

A growing number of people are now visiting the Southeast Asian paradise not for a swim at Phuket or trek in Chiang Mai, but for another commodity: Thailand’s low-cost and high-quality health care options.

Thailand is one of the most popular destinations for medical tourism in the world. More than 1.4 million people sought medical attention in the “Land of Smiles” in 2010, and more than 2.4 million people are expected to visit by the end of 2013, according to estimations by the Tourism Authority of Thailand.

Thailand is one of the most popular destinations for medical tourism in the world. More than 1.4 million people sought medical attention in the “Land of Smiles” in 2010, and more than 2.4 million people are expected to visit by the end of 2013, according to estimations by the Tourism Authority of Thailand.

Like almost everything else, health care is becoming globalized, and medical services are being outsourced. All over the world, people with financial resources are looking beyond the borders of their own countries to receive medical care and take full advantage of options available abroad.

In principle, there’s nothing new in this. For decades, wealthy people in developing nations sought medical care in weathier, more industrialized countries. In fact, the US was once a prime destination, with thousands of well-off people flying in each year to take advantage of services and procedures not available at home.

What’s changed is the number of people traveling for healthcare, and the direction of that travel. Rather than hosting medical travelers, Americans and Europeans are now the ones doing the traveling—and in large numbers!

Countries like the United Arab Emirates, Mexico and Costa Rica are successfully making names for themselves as hotspots for medical tourists. In this relatively new economy, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is determined to safeguard a prominent place for Asian countries, according to Dr. Siripen Supakankunti, an associate professor at Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University and a specialist in international trade in health services.

Botox on the Beach

Regionally, India’s medical centers boast the lowest prices, but its infrastructure can be less than user-friendly. Thailand tends to group itself with co-ASEAN members Singapore – which is pricier for patients, but unparalleled in ritziness – and Malaysia, somewhat of a newcomer on the global healthcare scene.

Medical consumer information guide, Patients Beyond Borders, says that while India, Singapore and Malaysia are industry heavyweights in the region, Thailand still holds the title “the rightful wellspring of contemporary medical tourism.”

Bangkok’s Bumrungrad International Hospital makes several Top 10 medical tourism destination lists, and Bangkok Hospital is the center of the third-largest hospital network in the world.

Private companies have worked hard to establish the infrastructure necessary to bring foreign patients in their doors, but it doesn’t hurt that Thailand is full of exotic cultural landmarks and breathtaking  nature.

nature.

To help bring visitors, the Tourism Authority of Thailand maintains a swanky website devoted to the industry, where enterprising health care seekers can cross-reference the treatment they’re seeking with the locale they desire. Botox on the beach? Knee surgery in the big city? Just choose from the drop-down menu.

Thriving During Hardship

Thailand’s medical tourism industry has shown a tendency to thrive during times of hardship.

In the early ’90s, Thailand was booming. A strong baht and thriving economy lead many Thai banking institutions to borrow foreign currency to invest domestically – largely in real estate development. The Thai government spent billions trying to keep the baht stable and protect it from speculative attack.

By 1997, investors began pulling out. On July 2, 1997, Thailand gave in to market pressures and devalued the baht. The baht went from 25 baht per US dollar to nearly 49 baht per USD over just a few months.

This collapse wasn’t isolated to Thailand; it soon spread throughout Asia. The 1997 Asian financial crisis wiped out billions from the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and even led to the US stock exchange’s temporary suspension that October.

Many Thai companies holding sizeable foreign debt lost substantial amounts, and development ground to a halt. Today in Bangkok, half-finished apartment complexes and office buildings still bear testament to the crash.

Private Thai hospitals, which had invested heavily in development during the boom years, found themselves overwhelmed if they held foreign debt. For other institutions, it was a pivotal moment, according to Dieter Burckhardt, a marketing communications and branding manager of Bankgok Hospital.

“This is where hospitals who were clever enough to stay solvent, that is to say, those who didn’t have foreign debt, were in a position where the dollar was extremely strong,” Burckhardt said. “The European currencies were very strong.”

Those hospitals – like Bangkok Hospital and Bumrungrad International Hospital – were able to turn a potential disaster into an opportunity to open their doors to international visitors, who were only too happy to take advantage of Thailand’s low costs.

“This is kind of how these markets learned about Thailand in the first place,” Burckhardt said.

In 2001, Thailand got another boom by way of crisis. After the Sept. 11 attacks, wealthy residents of countries like Qatar and the United Arab Emirates started finding it more difficult to access the US and Europe. Middle Easterners accustomed to flying to Royal London Hospital or the Mayo Clinic started looking for alternatives. They found them in places like Bangkok, where the weather was warm, the medical treatment was excellent, and the service was pristine.

Restaurants, Prayer Rooms, Donut Shops

More than 10 years later, Thailand’s medical visitors have surged. According to Wilaiwan Twichsri, Thailand’s deputy governor for tourism, the Thai Ministry for Public Health recorded roughly 500,000 international patients treated in 2001. In 2013, the ministry estimates about 2.4 million foreign patients will seek treatment in Thai facilities. The increase has been dramatic, despite a drop in 2007 during Thailand’s political turmoil.

In 2012, the medical tourism industry created estimated revenue of 140 billion baht (about $4.5 billion), including revenue from private hospitals, tourism and spa and massage care.

But this is far from easy money. Opening a hospital’s doors to foreign patients isn’t just a matter of hiring an English-speaking front desk staff, Dr. Siripen said. “Not all the private hospitals can really participate in medical tourism. It’s not easy.”

Thai facilities that do cater to international clientele must keep abreast of their patients’ wants and needs—which may vary quite a bit depending on country of origin, religion and ethnicity. Medical travelers in Thailand come in all shapes and sizes, and for all reasons.

Bangkok Hospital has a medical service center for its Middle Eastern patients, which includes lavish prayer rooms and doctors and nurses fully fluent in Arabic. It has similar centers for its patients from Japan, Myanmar and Bangladesh, and is developing a center for Chinese patients. The hospital system also recently completed a four-story mall attached to the main hospital’s building which Mr. Burckhardt says he is “loathe to admit” includes two Starbucks and one Dunkin’ Donuts.

Bumrungrad International Hospital’s 1 million square-foot facilities feature a heliport, more than 500 inpatient beds, more than 4,700 employees and a 10th-floor Sky Lobby with six international restaurants inside.

According to Dr. Siripen, the majority of foreigners who seek medical treatment in Thailand are expatriates or tourists on vacation, and needing minor procedures. In terms of revenue, however, it’s the patients seeking major treatments that bring in the money.

In 2012, Bangkok Hospital treated more than 800,000 patients; 200,000 of those were foreigners. While they accounted for about 25 percent of all visits, their procedures brought in 40% of the hospital’s revenue that year, Burckhardt said.

“Which makes sense, because they’re not coming in for upset stomachs or headaches,” he said.

Middle East & Mid-West

Medical tourists from the Middle East account for much of Thailand’s medical revenue. But a sizeable chunk also comes from Thailand’s next-door neighbors. The quality of health care in countries like Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos is generally quite low, and residents have traveled to Thailand for care for some time.

“They’ve just always come to Thailand for advanced care, for better doctors, for better technology,” Burckhardt said.

Americans, on the other hand, travel to Thailand to save money. An uninsured American in need of bypass surgery might not be willing or able to shell out $100,000 for the procedure. In Thailand, the surgery might cost a quarter of that, plus airfare. Thailand has numerous hospitals accredited by the Joint Commission International – widely seen as the gold standard for international hospitals – and patients feel they are in safe hands.

Other visitors are what Burckhardt calls “opportunity cost visitors” – people who have access to health care but can’t get it in a timely manner. For example, in Australia, where a fairly established universal health care system is in place, people have access to quality healthcare. If you need a knee replacement, you can get it. “The downside is you might have to wait 18 months,” Burckhardt said. “That’s a long time to wait if you can’t walk.”

Whatever the reason for bringing in medical tourists, Thailand seems to please them once they are here. Burckhardt said this isn’t just due to the medical expertise and resources of its doctors, but the level of service and destination quality of the country.

Eager to Please

“I’m not talking about necessarily having a surgery and then jaunting off to a beach to play volleyball,” he said. “That’s a pretty picture, but it doesn’t really happen very often. It’s the complete package.”

Thailand’s medical tourism industry is no longer just medical, Dr. Siripen said. In governmental documents and meetings, “health tourism” is now the preferred term. Spas offering Thai massages, acupuncture, relaxation seminars and detoxification services are on the rise. Some facilities are already well established.

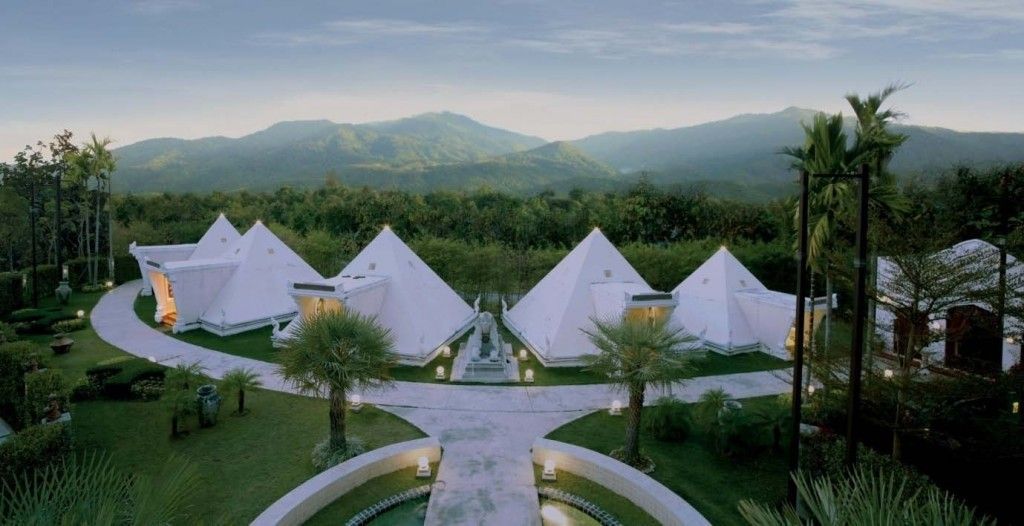

The Tao Garden Health Spa and Resort located outside Chiang Mai, is a veritable paradise of lush green trees, Tai Chi gardens, bubbling fountains and wooden gazebos. Guests–typically from the US or Europe–can choose from a variety of service packages: detoxification, chronic pain management, weight loss, de-stress or fasting.

Tao Garden maintains a footing in Western allopathic medicine—it has a lab for blood work, is staffed by Western trained physicians, etc—but the facility is run by Taoist Master, Mantak Chia, and has a heavy emphasis on energy work. “We really do try to integrate at the most basic level,” said Dr. Jabu Munalula, a US-trained surgeon who helps run the resort’s clinic. “We’re not just some sort of a frou-frou spa.”

Dr. Munalula said that while the resort isn’t cheap for patients, it’s much less expensive to run it than it would be in the US.

Guests may pay a premium to visit facilities like Tao Garden, but Dr. Munalula said they get exponentially more face-time with him than did his patients back in the US. When he worked in private practice, Dr. Munalula said he saw about 50 patients per day, and maybe had 5 minutes with each of them.

“Here I get to spend an hour sitting with my patients and getting to know everything about them, and I’ll probably see them the next day and maybe have lunch with them,” he said.

Brain Drain & Fiscal Strain

While medical visitors have doubtless brought income to Thailand’s national economy, there are some who protest the Thai government’s unquestioning support of the industry. Dr. Siripen said some critics have raised concerns about the effects of medical tourism on the quality of health care for the general Thai population.

“You cannot find consensus among Thais,” Dr. Siripen said. “Some agree, some disagree on medical tourism.”

The main concern is that private hospitals serving Westerners will attract all the best doctors with lucrative salaries and posh conditions, creating an “internal brain drain.”

But Dr. Siripen contends that internal brain drain can’t be directly attributed to the hospitals targeting foreign visitors.

Thailand implemented its universal health care plan in 2001. Predictably, many of the country’s most proficient and experienced physicians and nurses moved en masse to the private sector, where salaries can be two to three times higher higher and the hours are shorter.

“Workload is a problem for the public doctors in the public hospital,” she said. “If you would like to retain them in the public (sector), you have to find a way.”

Medical tourism may be perpetuating these dynamics, but Dr. Siripen maintains that the industry certainly didn’t create them.

Burckhardt believes the resources created by medical tourism have actually allowed many Thai physicians who had been practicing abroad to move back to Thailand. More than 10% of Bangkok Hospital’s physicians are board certified in the US, Australia or Europe, and spent time practicing in those countries. Without salaries at hospitals supported by foreigners, it is unlikely they would be able to afford the move back to Thailand.

Medical tourism does have a tendency to drive up the local cost of medicine to any level that foreign patients are willing to pay; Dr. Siripen said that while in the past, many middle-class Thai families could comfortably afford the fees for private healthcare options, that’s no longer the case.

Beyond Medical Tourism

Officially, Thailand is not content to be merely a medical travel destination. “We would like to achieve what we call a medical hub,” Dr. Siripen said. This means a major beefing up of Thailand’s research resources and education capabilities.

Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health has a five-year plan to put Thailand on the map as a world-class health care provider. By 2018, the ministry hopes to have developed the country as hubs for wellness, medical service, academic research and productions.

The government also wants to make it easier for medical travelers to stay longer, by extending visitor visas from 30 days to 90 days for medical tourists from Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

On its immediate agenda, the ministry has plans to participate in upcoming travel health shows and media events to help promote Thailand’s reputation.

“Thailand’s medical and wellness entrepreneurs are so ready to expand markets all over the world to stress Thailand’s image as Asia’s destination of health and beauty tourism,” said Ms. Wilaiwan, the nation’s deputy governor for tourism.

END

Gabrielle Zastrocky is a multimedia journalist specializing in the fields of education and health care, and has strong interests in energy, religion and business. She is currently based in Chiangmai, Thailand.