Echinacea is consistently among the top selling herbal supplements in the US, and has been for decades. Many people take it as a go-to remedy for respiratory infections such as influenza and rhinovirus, and for general immune system support.

It’s no surprise that sales of this popular herb jumped by more than 50% in the wake of the COVID pandemic, and remain robust.

But, is Echinacea truly antiviral?

According to researchers at Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine’s new Ric Scalzo Institute for Botanical Research, the answer is: It depends.

The effect of Echinacea on viral replication is variable, depending on the type of virus in question, the particular species of Echinacea, and the extraction method used to prepare it.

There are three main species of Echinacea found in general commerce: E. purpurea, E. angustifolia, and E. pallida. They differ significantly in their levels of bioactive alkamides, phenols, glycoproteins, and polysaccharides. Within a given species, the biochemical profile also varies depending on which part of the plant is used to make the extract. The roots, leaves, and flowers produce different sets of compounds.

Microbiologist Jeffrey Langland, PhD, heads a research team at SCNM that has been studying the effect of Echinacea and its phytochemical constituents against a number of common human viral pathogens.

Divergent Effects

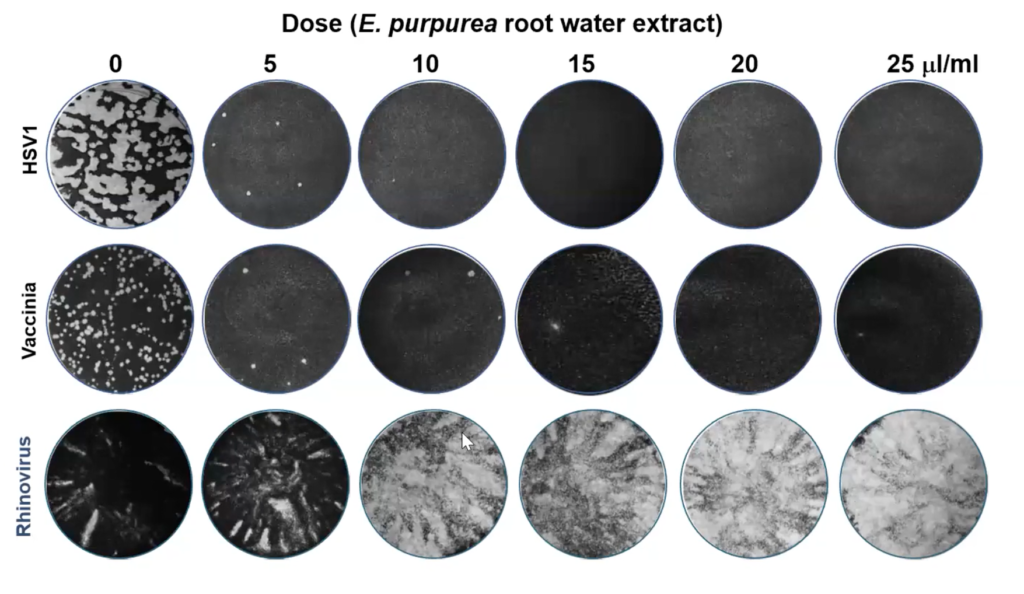

Utilizing petri dishes lined with monolayers of human respiratory epithelial cells, Langland and his team measured the impact of a 1:10 water extract of E. purpurea root on three different human viruses: Herpes simplex (HSV1), Vaccinia, and Rhinovirus.

Even at low concentrations, the root water extract was able to inhibit replication and growth of HSV and Vaccinia. The effect was readily visible, highly replicable, and consistent with the general belief that this herb is “antiviral.”

But with Rhinovirus, E. purpurea appeared to have the opposite effect. The SCNM investigators observed a consistent increase in the speed and vigor of viral spread in the treated cell cultures, as indicated by the number and size of the viral plaques on the cell monolayers.

This enhancement effect was on the order of 10 to 100-fold, depending on the concentration of the extract applied.

Langland and his team repeated the experiments with seven different E. purpurea water extracts, made from plants grown in different locations in different years. The general pattern was consistent: inhibition of HSV1 and Vaccinia, but enhancement of Rhinovirus.

They also tested the extracts against an encephalomyocarditis virus in the same viral family as Rhinovirus. Echinacea neither inhibited nor enhanced replication of this virus.

The bottom line is, the root extract inhibits some pathogens while promoting others.

“You cannot categorically say that this herb–or any herbal extract—is broadly ‘antiviral.’ These extracts did inhibit HSV and Vaccinia, but they enhanced Rhinovirus. So, it depends on which virus you’re talking about,” said Dr. Langland during a recent online SCNM Research Night presentation.

The Rhinovirus enhancement effect comes as a surprise, given that this herb has historically been used as a remedy for common colds. But it does partially explain why clinical trials of echinacea to mitigate respiratory infections have been so contradictory and equivocal.

Dr. Langland acknowledged that this current work is preliminary, and the SCNM team has not yet tested the extracts in human subjects. But the findings do suggest that people ought to think twice before brewing up a cup of Echinacea tea in the hope of quelling cold symptoms.

These provocative discoveries open up a whole jarful of “how” and “why” questions, which Langland and his team are working to answer.

Enhanced Replication

To explain the enhancement effect, they initially hypothesized that some constituent in Echinacea inhibits host defense mechanisms, specifically the interferon response, since this is one of the most well-characterized physiological responses to viral infections.

But conjecture that did not hold up to scrutiny. When interferon was infused into echinacea-treated and untreated rhinovirus cultures, both showed a 10-fold decrease in viral spread, suggesting that the herb does not affect interferon.

Apoptosis is another key host defense mechanism, and the SCNM team again hypothesized that Echinacea may somehow interfere with this process, enabling infected cells to survive, thus promoting viral replication. But when they tracked viability of rhinovirus-infected cell cultures, they found little difference between those treated with Echinacea and the untreated controls plates.

It’s possible that, rather than derailing host defenses, there’s something in Echinacea that directly promotes viral replication, assembly, or release.

Based on assays of protein synthesis, they saw a 2.5-fold increase in the presence of viral proteins in Echinacea-treated samples compared with untreated samples. “The root water extract is able to enhance the level of protein synthesis pretty dramatically, potentially making more virus particles,” Dr. Langland said.

The SCNM group also looked at changes in protein kinase R (PKR), an intracellular enzyme that is phosphorylated as it binds to viral RNA. A change in the level of phosphorylated PKR is a strong indicator of an increased presence of viral RNA.

In the presence of echinacea, infected cells showed marked increases in levels of PKR phosphorylation compared with infected but non-treated cell samples.

“This was a huge, dramatic increase in the activation of this (PKR) protein,” said Dr. Langland. More than likely, the echinacea root water extract is increasing viral RNA synthesis. How it’s actually doing this is a question we will continue to work on.”

Ethanol vs Water

The finding that water extracts of Echinacea can inhibit replication of some viruses while enhancing others is surprising enough. But the story doesn’t end there.

According to Keely Puchalski, ND, a member of Langland’s research team, ethanol extracts of the same plant do inhibit rhinoviruses.

Puchalski and her colleagues made 65% ethanol extracts of ground E. purpurea roots, and tested these tinctures using the same in vitro model as was used in the water extract experiments. But in contrast to the Rhinovirus enhancement pattern seen with the water extracts, they saw clear and replicable evidence of viral inhibition with increasing doses of the ethanol extract.

“At just 5 microliters per mL, we were seeing an 80% plaque reduction. By 10 microliters, it is close to 100%.”

Why the big difference between water and alcohol preparations of the same plant?

Alcohol and water pull different compounds out of the plant material. In other words, the phytochemical profile of an extract will differ—sometimes markedly—depending on what sort of solvent is used.

Dr. Puchalski believes the anti-rhinovirus effect is due to a blocking of viral attachment to host cell membranes. At 5 microliters per mL, there’s a 35% reduction in viral attachment to uninfected cells. At 10 microliters per mL, there’s an 80% reduction.

Ethanol draws out four main classes of compounds from Echinacea root: alkamides (alkylamides), caffeic acid derivatives (phenolics), glycoproteins, and polysaccharides.

Dr. Puchalski contends that it is the alkamides—the compounds that cause the mouth-tingling or numbing sensations associated with Echinacea—that are primarily responsible for the antiviral effect.

The SCNM group tested a number of Echinacea-derived compounds against rhinovirus-infected cell cultures. The caffeic acids neither inhibited nor accelerated viral growth. On the other hand, the four alkamides they tested were clearly antiviral. “At 16 mcg per mL, we saw that all appeared to be completely inhibiting rhinovirus.”

One compound known as alkamide C was particularly efficient in inhibiting rhinovirus.

She noted that alcohol extracts made from the stems, leaves, and flowers of E. purpureaalso squelched virus, though not nearly to the extent seen with the root extract, which is much more active at much lower concentrations.

In terms of its impact on viral pathogens, Echinacea is chimeric. Water extracts of the root inhibit herpes and pox viruses, but not rhinoviruses. Ethanol extracts of the same root will inhibit rhinoviruses. SCNM researchers have not yet tested the alcohol extract against other types of viruses.

Like so many things in nature, the biological effects of this plant are far more complex than our simple “yes/no” “good/bad” dualistic minds want them to be. The same will likely hold true for many other medicinal herbs.

One of the major objectives of the Scalzo Institute for Botanical Research is to increase the level of sophistication of herbal medicine research, and to elucidate the variables that influence the biological effects of herbs in common use.

END