Telemedicine has been the big winner in the COVID economy, and growth of this sector has shown no sign of slowing.

In 2020, as the COVID-19 crisis forced practitioners, patients, and legislators to recognize the need for expansion of telehealth, the global market for digital healthcare services reached an estimated $152.5 billion. Researchers project that the industry — which comprises digital health systems, healthcare analytics, and telemedicine — will grow to $456.9 billion by 2026.

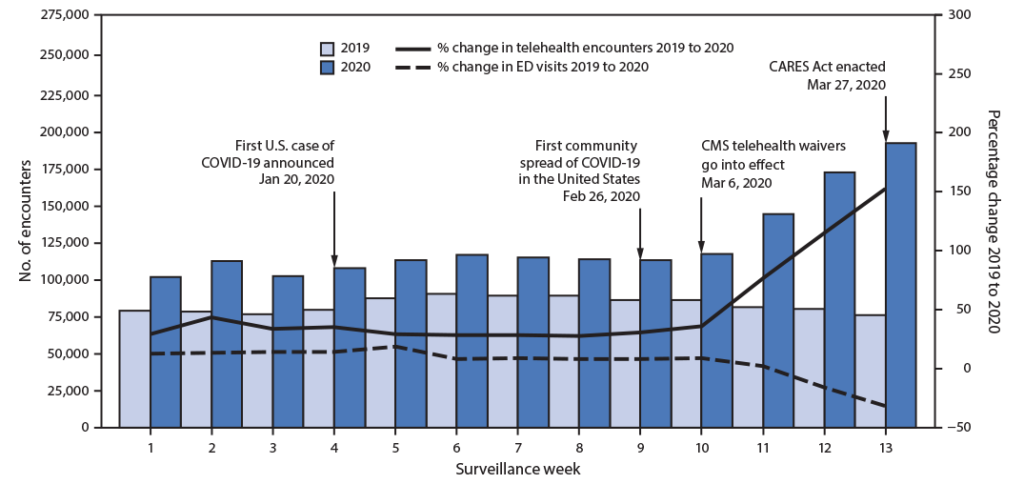

The use of telemedicine services in particular skyrocketed in early 2020. A CDC report shows that in the first quarter of that year, the number of virtual healthcare visits increased by 50%, compared with the same period in 2019. In the last week of March 2020 alone, telemedicine visits jumped 154% over the number of visits that same week in 2019.

That acceleration continued in 2021. By one account, ten times more telehealth visits occurred in March 2021 than in March 2020.

Big Tech is paying attention to these trends. About a year ago, Google announced a major $100 million investment in Amwell, one of the largest telehealth service providers.

Amwell’s revenue jumped from $69 million to $122 million — a 77% increase — in the first six months of 2020, according to its IPO filing. Alongside other recent developments the company noted the significant reduction of regulatory and reimbursement barriers for telehealth, surging demand for on-demand remote COVID-19 services, and a desire to protect healthcare workers and patients from people infected with coronavirus.

Stay-at-home orders and business closures also boosted the popularity of fitness apps and “smart” exercise equipment.

Millions of smartphone users downloaded meditation and sleep apps like Calm and Headspace, programs that promise better rest, lower stress, and less anxiety.

A host of digital health platforms now offer quick, discreet, on-demand access to medical services. They can also eliminate long wait or travel times to receive medical attention. The trade-off for convenience means that health tech users accept the risk of their sensitive personal data being hacked or used in ways that aren’t initially intended or clearly disclosed.

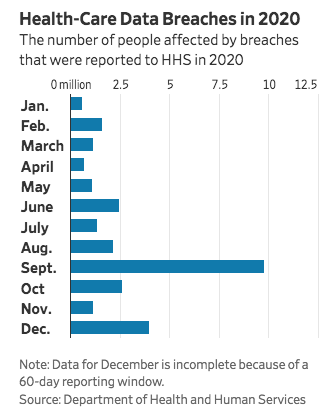

Threats to data privacy have worsened since the pandemic began. Cyberattacks on healthcare institutions spiked last year, as Forbes and others reported earlier this Summer. For the fifth straight year in a row, hacking incidents rose again in 2020, up a striking 42% from 2019.

The increase in healthcare hacking events raised enough red flags that in October 2020, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Department of Health and Human Services, and FBI issued a joint cybersecurity advisory warning of “an increased and imminent cybercrime threat to U.S. hospitals and healthcare providers.” They cautioned healthcare institutions to “ensure that they take timely and reasonable precautions to protect their networks from these threats.”

Leaked healthcare data — the presence of pre-existing conditions or potentially “embarrassing” diagnoses — can unknowingly affect the ability to obtain life insurance, the amount paid for coverage, or the interest rates they’re charged on loans. In the wrong hands, health data shared without a patient’s knowledge can also result in workplace discrimination.

END