It’s one of the biggest public health challenges confronting the nation, an issue that will sooner or later touch just about everyone regardless of race, creed, ethnicity or economic status. But nobody really wants to talk about it.

It’s one of the biggest public health challenges confronting the nation, an issue that will sooner or later touch just about everyone regardless of race, creed, ethnicity or economic status. But nobody really wants to talk about it.

It comes down to this: there are not enough caregivers to meet the growing needs of the nation’s rapidly aging population.

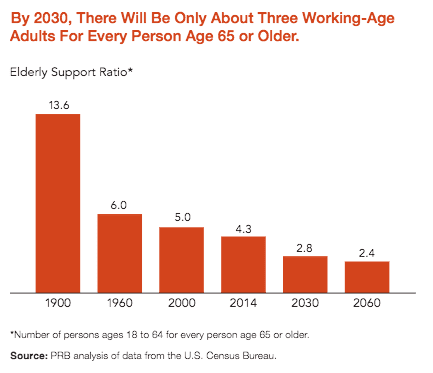

At a time of soaring demand for ongoing medical care, home-based healthcare, and social services, the number of people able and willing to provide these services is declining.

That equals a slow-motion disaster for the nation’s elderly and infirm, says Ai-jen Poo, founder of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, and Caring Across Generations.

Speaking at Stanford University’s 2017 Medicine X conference, Poo stressed that the impending caregiver crisis cuts across all demographic, political, and social boundaries. The question of how we will care for our elderly is at once deeply personal and profoundly universal.

“It’s hard to imagine too many issues that touch so many people as this one.”

Poo’s work in advocating for the ill and the elderly—and for fair pay for those who take care of them—has been widely praised, and it won her a MacArthur Fellowship grant in 2014.

Echoing a famous statement by former First Lady, Roslyn Carter, she stated: “There are only four kinds of people in the world: people who are caregivers; people who will be caregivers; people who need care; and people who will need care.”

“We need more care than we ever could have imagined when the social safety nets were put in place. We are living in a completely unsustainable situation…A crisis like this screams opportunity. I’ve never worked on an issue where there are more stakeholders. Everyone has an interest in this.” — Ai-jen Poo, at Stanford’s 2017 Medicine X conference

In the US, and in most industrialized nations, those latter two categories—people who need care or will soon need care—are  expanding very fast.

expanding very fast.

Consider the statistics:

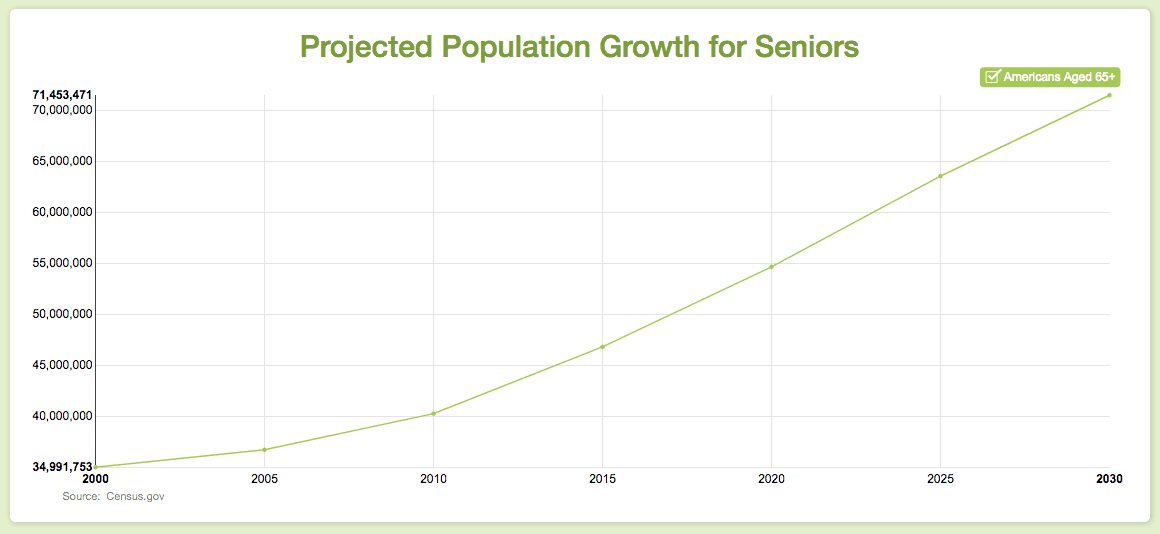

- There are already 5 million Americans over 85, according to the US Census Bureau. Octogenarians represent the nation’s fastest growing age bracket.

- Every day, roughly 10,000 Americans hit their 65th birthdays. That’s almost 3.7 million each year. People over 65 now represent 14.5% of the total US population, up from 12% in 2000.

- With a life expectancy of 76 years for men, and 81 years for women, people over 65 are likely to live many more years than did those who reached retirement age in the 1950s.

- The number of older Americans needing nursing home care is expected to hit 2.3 million by 2030, up from an actual 1.3 million in 2010, according to the Population Reference Bureau.

- In 2013, there were 5 million people living with Alzheimer’s disease. That’s expected to nearly triple to 14 million by 2050.

- In contrast, people between the ages of 26–34 represent just 12% of the population; those in the 35-54 bracket—the prime caretaker years—are only 26% of the total. Growth in these brackets is not keeping pace with the expansion of the over-65 segment.

- The Millennials—a smaller generation that the Baby Boom–are having roughly 4 million babies per year. Faced with a challenging economy and wage stagnation, many spend more time at work and less with family, increasing the need for childcare. More than 75% of kids grow up in households where all the adults work.

Unlike past eras in which most elderly people lived with spouses or family members, many of today’s seniors are alone. According to the Population Reference Bureau, 27% of all women aged 65-74 lived alone in 2014. For women 75-84, the number rises to 42%.

These are massive demographic shifts, with profound impact on all aspects of society.

The “Panini Effect”

“At a time when we need more care than ever before, we actually have less of it, because the traditional default care system–women who stay at home–is not there anymore,” Poo told Medicine X attendees.

She described what she terms the “Panini Effect”—a sandwich generation of people, mostly women, who are struggling to care for their children, and in some cases grandchildren, as well as their aged parents all while under tremendous economic and social pressure.

Approximately 43.5 million Americans are caregivers for aged or ill people. “It’s a big number, but in no way does it match the emerging need,” said Poo, who is the author of a book called, The Age of Dignity: Preparing for the Elder Boom in a Changing America.

For many families, paying for care is not an option. The economics simply do not—and cannot—work:

- 75% of the full-time workforce earns less than $50,000 per year.

- The median cost for a one-bedroom apartment in a senior assisted living community is $43,539 annually. It ranges from roughly $30,000 (Missouri) to $80,000 (District of Columbia), according to Consumer Reports.

- The average cost of a private room in a full-service nursing home is over $87, 000 per year.

- At the other end of the age curve, childrens’ daycare costs an average of about $20,000. In the last 25 years, childcare costs have doubled.

Medicare does not cover in-home elder services. Medicaid covers limited homecare, but only for those at or below poverty. Private long-term care insurance starts at about $80 per month for a bare-bones plan. At best, only 16% of non-Medicaid eligible Americans over 65 have bought in.

“We need more care than we ever could have imagined when the social safety nets were put in place. We are living in a completely unsustainable situation,” Poo said.

This is not just a social issue; it is a medical one. Acute interventions certainly save lives, but long term health—and prevention of readmissions—depends far more on what happens at home than what happens in hospitals or clinics. When people lack basic help and support, the net impact of potentially effective clinical interventions is blunted.

A No-Win Situation

Demand for care may be soaring, but wages for caregivers are not.

Homecare workers typically earn $10 per hour or less, with few if any benefits. They take home a median of roughly $13,000 annually.

Poo estimated that 30% of homecare workers are reliant on public assistance for food security. The very people on whom  millions of families depend to look after their youngest and their oldest—are struggling desperately to make ends meet, and are often forced to neglect their own families.

millions of families depend to look after their youngest and their oldest—are struggling desperately to make ends meet, and are often forced to neglect their own families.

Needless to say, employment prospects in home-based eldercare are not very attractive: the hours are long, the work is demanding, the pay is low, and there are few labor protections like sick days, vacation time, or healthcare benefits.

Domestic workers are disproportionately Black and Latino/Latina. Many are recent immigrants with few other employment options. They are vulnerable to physical, sexual, and economic abuse. There’s much exploitation, and little security (see Who Cares for the Au Pairs?).

Ultimately, it’s a no-win situation: many families cannot afford the care their elder’s need, while paid caregivers are often treated as expendable low-paid laborers unable to earn real living wages.

Choosing to Ignore It

Unlike the physician and nurse shortage, which has provoked at least some degree of public hand-wringing, the imminent shortfall of eldercare workers seldom makes headlines. As a policy issue, it is largely invisible.

Generally, Americans frame the issue of care giving as a personal, private matter, not a public one. The discussions are happening at millions of kitchen tables throughout the nation, but these are “behind closed doors” conversations.

Though the aging of the population is a massive societal issue–one could argue it’s one of the biggest— on a policy level we have more or less chosen to ignore it. But, as with climate change, the demographic realities will have their impact whether or not we acknowledge them.

“A crisis like this screams opportunity. I’ve never worked on an issue where there are more stakeholders. Everyone has an interest in this,” Poo told Medicine X.

An Infrastructure of Caring

Through Caring Across Generations, the advocacy organization she co-directs, Poo has been working since 2011 to make eldercare a front-line political issue, and to develop what she terms a public “care-giving infrastructure” akin to the physical infrastructure that brought clean water into nearly every American home, or the technological infrastructure that underlies the internet.

CAG represents more than 200 organizations, and works at the federal, state, and local levels toward three broad goals: 1) Increased access to safe, high-quality, and affordable long-term home care for the ill and elderly; 2) Greater public financial support for families of elders; and 3) Better wages and working conditions for professional caregivers.

CAG represents more than 200 organizations, and works at the federal, state, and local levels toward three broad goals: 1) Increased access to safe, high-quality, and affordable long-term home care for the ill and elderly; 2) Greater public financial support for families of elders; and 3) Better wages and working conditions for professional caregivers.

CAG is calling for sweeping federal policy that simultaneously addresses multiple entwined issues that affect eldercare. Specifically, the group is advocating for:

- A National Holistic Long-Term Care System: that would give families increased access to home-based care, while distributing risk and incorporating a national plan to recruit, train, and retain care workers. This vision includes a tax-funded “Universal Family Care” insurance.

- Paid Caregiver Leave: for working people who are also caring for elders.

- De-Institutionalization of Eldercare: Despite studies proving that home care services cost less than similar services in nursing homes, public programs still default to institutions. Many states report rising Medicaid expenditures for nursing home care, a trend CAG hopes to reverse.

- Income Credits Toward Social Security: for individuals who reduce work hours or leave the workforce to care for a child or an ill, disabled, or aging family member.

- Lifting Asset Qualifiers for Medicaid Long-Term Care: Current rules require families to spend down their savings to poverty levels before qualifying for long-term care. This discourages savings and leaves millions highly vulnerable. CAG proposes pegging asset limits to inflation rather than fixed cut-offs.

- Training Family Caregivers: Family members often care for loved ones without access to good medical information or basic training. Caregiver education programs could improve elder health by giving family members a modicum of basic skills.

- Raising Wages for Professional Care Workers: CAG is calling for a minimum wage of $15 per hour for homecare workers, along with better occupational protections, basic benefits, and training to raise skill levels.

- Domestic Workers Bill of Rights: In 2010, New York State passed a bill aimed at increasing benefits and rights for housekeepers, nannies, childcare workers, and in-home eldercare givers. Since then, other states including California, Nevada, and Hawaii have followed suit. CAG is working with many states on similar legislation.

- Citizenship Pathway for Immigrant Care Workers: Many homecare providers are undocumented immigrants; they live under constant threat of discovery and deportation. A clear path to citizenship for them would help fill the labor gaps and provide greater security for families already receiving care from these immigrants.

- Support for Young Caregivers:There are more than 1.4 million people under age 18 providing care for family members. They seldom have the needed training, and must constantly balance family needs with school and job demands. CAG is calling for eliminating age qualifiers in the formal definition of care giving, coupled with training programs and financial support specifically for these young caregivers.

The key to preventing a socioeconomic disaster around eldercare, Poo told Medicine X attendees, is to make caring a national priority and a viable way to earn a living. “If we could make care jobs good, sustainable jobs, we could transform so many things—both for the workers, and for the recipients of care.”

She believes there’s no way around the need for government involvement. No doubt, that will be a hard sell in the current political environment.

But Poo says in the course of her work she speaks with legislators, business leaders, and community advocates from across the political spectrum. Even the most hardcore pro-business conservatives acknowledge that the looming crisis cannot be managed solely with, “market based solutions.”

Signs of Hope from Hawai’i

It may be a long time before the magnitude of the problem breaks through the toxic political rancor in Washington. But at the  state level, it seems some legislators are waking up.

state level, it seems some legislators are waking up.

In July 2017, the Aloha State set an example for the rest of the country by passing the Kupuna Caregiver Assistance Act—the first state-funded program to provide financial support for people caring for aging parents or grandparents at home. Kupuna—the Hawai’ian word for elders—offers up to $70 per day for adult daycare, chore services, home-delivered meals, housekeeping, personal care, respite care or transportation.

To qualify, caregivers must show they are actively tending an impaired elder (60 years or older) not covered by comparable governmental care plans, while also employed for at least 30 hours per week outside their homes.

The funds will be administered by the state’s Executive Office on Aging, and distributed by County Area Aging Agencies. The government claims it is tax-neutral and entirely supported by existing state revenue.

Because of the state’s unique geography and population distribution, home healthcare in Hawai’i costs almost $10,000 more per person per year than the national average. Advocates of Kupuna Caregiver Assistance say the program will improve health and quality of life for the islands’ 120,000-plus seniors while allowing younger people to stay in the labor force. It will also create good employment opportunities in the homecare sector.

Hawai’i is also experimenting with mixed-generation care centers that bring elders and children together in the same facilities.

Other states, including Washington, are considering eldercare assistance programs modeled on Hawaii’s Kupuna act.

The Ultimate Transpartisan Issue

In Minnesota, Illinois, and Maine, some legislators have begun calling for state versions of the Universal Family Care idea forwarded by CAG.

In Maine—where citizens voted in favor of a referendum to expand Medicaid despite strong opposition from the state’s Republican governor—a universal family care proposal has already been introduced to the state legislature. If passed, the program, to be funded by a payroll tax on annual incomes over $118,000, could be implemented by 2021.

In 2016, Detroit area voters elected Darrin Camilleri—a young Democrat who’s made eldercare a priority—to the state’s house of representatives. Camilleri, who won in a district that voted overwhelmingly for Trump, has publicly acknowledged that family care issues put tremendous financial strain on his constituents.

Poo praised all these developments as steps in the right direction, and indications of a movement to bring caregiving issues out of the shadows of isolated private conversation and into the light of public discourse about the nation’s future.

“In the realm of politics, we have been doing voter education around the issue of caregiving for last five years—it really does reach across partisan lines. This is the ultimate transpartisan issue,” she noted. “People are touched by it, moved by it. They want and need better solutions. And recently, candidates have begun to show interest.”

Her organization has also been working with corporate leaders who see the need to change policies around family caregivers, workplace flexibility, and paid leave.

CAG is building partnerships with television and film producers, to bring narratives about caregiving into pop culture. The group played an advisory role in the 2014 film, Still Alice, starring Julianne Moore as a linguistics professor struggling with early onset Alzheimer’s, and was deeply involved in the recent PBS documentary, Care.

“The sharing of care stories is a really important aspect of Caring Across Generations. It is an incredibly important source of power.” The statistics, she says, speak for themselves. But it is really the stories that move people to action.

And on the issue of eldercare, we need action.

“This is an “all hands on deck” situation. We need everyone involved,” she stressed. ‘We are living in tough times. But it is precisely times like these that need bold action, especially around something that can bring us all together. The risks of not doing anything on these issues are huge.”

END