Mangos. They’re cheery, packed with vitamin C and other nutrients, and though they’re quite sweet, they can improve insulin sensitivity in people at risk of type 2 diabetes.

That’s the upshot of a recent clinical trial from researchers at the Clinical Nutrition Research Center at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

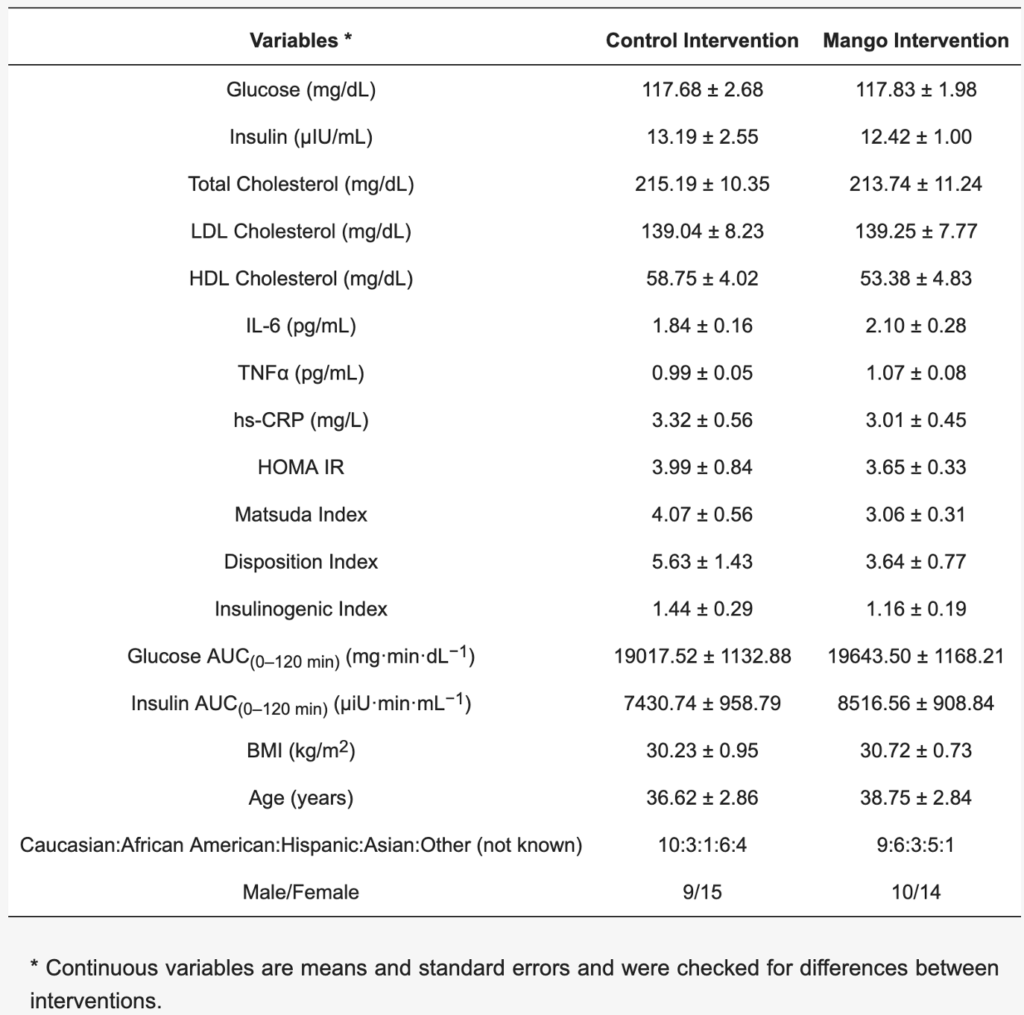

Katherine Pett and colleagues studied 48 obese or overweight adults, all of whom also had baseline blood biomarker profiles indicating low-grade systemic inflammation.

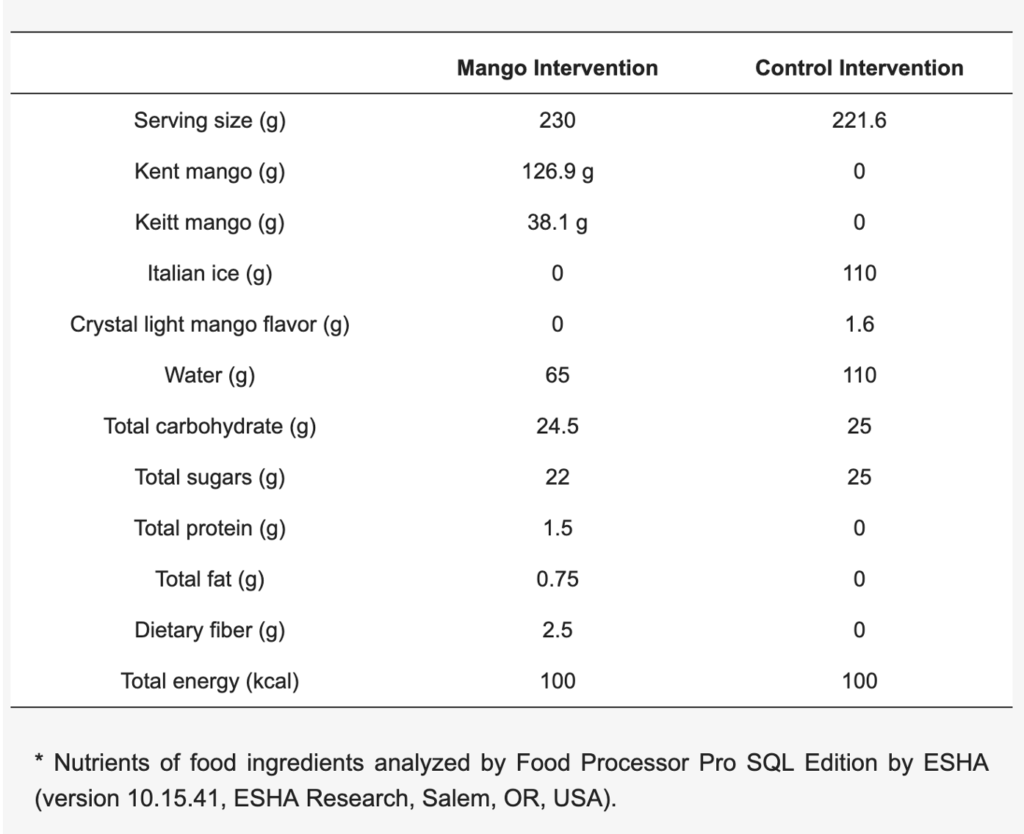

They were randomly split into two groups: one group was given a twice-daily supply of blended and frozen fresh mango pulp (containing both Keitt and Kent varieties); while the other group was given a supply of mango-flavored Italian Ices, matched for total sugar and caloric content, but containing no actual mango pulp.

The researchers instructed the participants to eat two cups (roughly 5.5 oz per cup) of their assigned treat each day—one in the morning and one in the evening. Over the course of the four-week trial, the subjects all followed their habitual diets none of which were particularly ‘health-conscious.’ The protocol did require them to avoid eating additional mangos and other high-polyphenol produce during the trial period.

None were taking prescription drugs or supplements that could potentially modulate glucose metabolism.

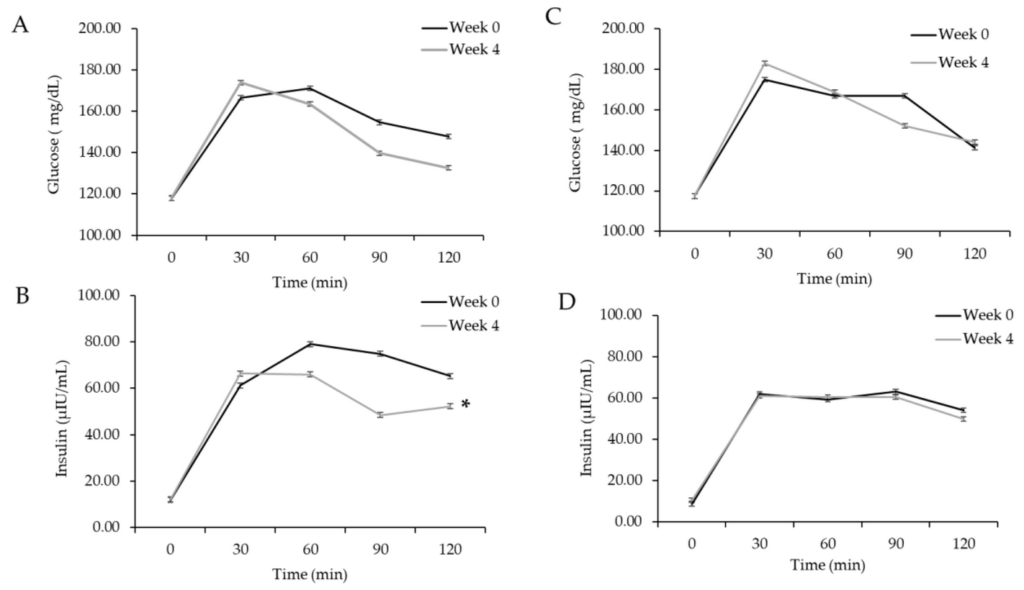

At baseline, and again at the end of the fourth week, the subjects underwent oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTT). The tests were done in the morning, following consistent dinner meal the previous night, covered by the study protocol (to minimize the variable impact of diverse meals on glucose and insulin levels).

In addition to the OGTTs, the researchers also measured basic biometrics, vital signs, body composition, and subjective experiences, five times over the month-long study.

To assess systemic inflammation, Pett and colleagues measured serum levels of IL-6, TNF-α, and high-sensitivity c-reactive protein (hs-CRP).

Significant Impact

“The primary working hypothesis of this project was that regular mango intake would reduce inflammation in individuals with chronic low-grade inflammation, resulting in increased insulin sensitivity. This hypothesis stems from data indicating that inflammation is a mechanism that contributes to insulin resistance, and data in preclinical and clinical models that suggest that mango or its components have anti-inflammatory activity,” the authors write (Pett KD, et al. Nutrients. 2025).

Pett’s team found that while daily mango consumption did indeed improve insulin sensitivity, this was not exactly via the anti-inflammatory mechanism they had expected.

The insulinogenic index (II)—an indicator of how well a person’s beta cells respond to a glucose load—was improved in the mango group versus the controls. Likewise, the disposition index (DI), which reflects the degree to which beta cells compensate for peripheral tissue insulin resistance, was significantly improved among the mango-consuming subjects.

At the close of the fourth week, fasting insulin concentrations were markedly lower in the subjects assigned to the mango group compared with those in the control group mango (8.2 ± 1.16 µIU/mL vs. 15.26 ± 1.18 µIU/mL, p = 0.05). There was also a statistically significant impact on HOMA-IR (Homeostasis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance) scores, which averaged 2.28 (± 1.19) for the mango group versus 4.67 (± 1.21) among the controls.

“Fasting insulin concentrations were significantly lowered with the mango intervention compared to the control intervention, and insulin resistance status was improved, evidenced by changes in HOMA-IR and disposition index.”

Fasting glucose concentrations, as indicated by the OGTTs, were not significantly different between the participants in the mango versus the control groups (119.67 ± 1.02 mg/dL vs. 116.95 ± 1.02 mg/dL, p = 0.51).

The mango intervention had no significant impact on any of the three inflammatory measures (IL-6, TNF-α, or CRP), which was somewhat surprising given the original premise underlying the trial. The finding calls into question the baseline assumption that inflammation is the key driver of insulin resistance.

An Antioxidant Effect

This is not to say that inflammation plays no role, but it does suggest that different mechanisms may also be in play. The IIT authors hypothesize that the observed changes may be due to changes in cellular redox activity induced by phytochemicals in the mangos.

“Mango intake daily for 4 weeks increased insulin sensitivity, reducing the amount of insulin required to maintain glucose in people with chronic low-grade inflammation, but the effect was not through an inflammation pathway”

–Katherine D. Pett & colleagues, Illinois Institute of Technology

Analysis of gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells turned up an interesting clue—a non-significant but measurable increase in mean expression of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) from baseline to study completion in the mango group, but not in the controls.

NRF2 regulates antioxidant protein synthesis that mitigate oxidative damage, so the finding gives some objective weight to the notion that an antioxidant effect may underlie some of the observed benefits from mango consumption.

The authors acknowledge that their study was done in the midst of the Covid pandemic, and that subjects’ exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and to various Covid vaccines might have affected their inflammatory marker profiles in a way that obscured anti-inflammatory effects associated with mango phytochemicals.

Though the role of inflammation in promoting insulin resistance is still something of an open question, the Pett data do show that insulin sensitivity can be altered in the absence of concurrent changes in key inflammation markers.

“Mango intake daily for 4 weeks increased insulin sensitivity, reducing the amount of insulin required to maintain glucose in people with chronic low-grade inflammation, but the effect was not through an inflammation pathway based on the markers measured in this study,” Pett and colleagues note.

No Weight Gain

They added that the insulinogenic index (II)—an indicator of how well a person’s beta cells respond to a glucose load—was improved in the mango group versus the controls. Likewise, the disposition index (DI), which reflects the degree to which beta cells compensate for peripheral tissue insulin resistance, was significantly improved among the mango-consuming subjects.

“Overall, the glucoregulatory indices associated with insulin sensitivity point toward a beneficial effect of mango intake at the level of the pancreas and the liver (and possibly peripherally), resulting in reduced insulin resistance.”

The IIT team saw no significant changes in fasting total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, or TGL among the participants in the mango group versus the controls. Likewise, they did not

observe any meaningful change in weight in either direction among the subjects in the mango group. In the control group, there was a slight trend toward weight gain—from a mean of 84.7 to 85.8 kg (± roughly 3 kg).

The high natural fructose levels in mangos can be problematic for people who are sensitive to FODMAPs

There’s no question that mangos are sweet. A one-cup serving (roughly 165 g) contains approximately 23g of natural sugar. This fact has led to a common belief that mangos should be on the Do Not Eat list for people dealing with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or obesity.

Pett’s study squarely challenges this notion. The people in the intervention arm were eating more than 300 grams of mango pulp every day for a month, yet they did not gain any weight.

The high fiber content of mangos may mitigate their overall glycemic impact. Overall, mangos have a glycemic index of 51-56 (depending on the type), which is considered medium, and they deliver a glycemic load in the range of 8.9 to 9.0, which is deemed low to moderate.

A Healthy, Nutritious Fruit

All that being said, the high natural fructose levels in mangos can be problematic for people who are sensitive to FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols). Many people have difficulty absorbing excess fructose, which gets fermented in the colon causing gas, bloating, and diarrhea.

Generally speaking, though, mangos are a healthy food. They’re high in fiber, very rich in vitamin C (~60 mg per one-cup serving), and they’re good sources of beta-carotene, folate, vitamin E, vitamin K, and a host of minerals including potassium, magnesium, calcium, and iron. They also contain a unique polyphenol called mangiferin, which has antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and glucoregulatory effects.

A one cup daily serving of mango provides 100% of the daily value of vitamin C, 35% of the daily value of vitamin A, and 12% of the daily value of fiber.

Pett and colleagues suggest that people who have—or are at risk for—disorders characterized by insulin resistance and dysregulation of glucose metabolism, would benefit from incorporating mangos into their diets.

“The data support consuming mango fruit as part of a dietary pattern to address insulin resistance and warrant further research to understand the mechanisms underpinning the actions of mango intake,” they conclude.

END