Be on the lookout for drug-induced magnesium depletions. That’s one of the major messages from a comprehensive new paper on the clinical impact of magnesium deficiencies recently published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Many of the most widely prescribed drugs, including diuretics, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and certain antibiotics, can cause magnesium wasting. Given how many people are on one or more of these drugs, it is likely that a large segment of the global population–and many of your patients– have iatrogenic magnesium-deficiency.

Most physicians do not routinely evaluate magnesium status. But they should, state Rhian M. Touyz, PhD, and colleagues of the Department of Family Medicine, McGill University, Montreal.

“Clinicians should be more attuned to the importance of magnesium,”

Significant Consequences

“Magnesium is a vital but poorly understood electrolyte in clinical medicine. It is often not measured as part of routine electrolyte screening,” says Dr. Touyz.

Hypomagnesemia is often asymptomatic, but this does not mean that it is inconsequential. Magnesium deficiency is associated with, and may play an etiological role in, a host of cardiovascular, metabolic, and neurological problems. It is common among hospitalized patients, and is predictive of prolonged ICU stays.

Deficiency is particularly problematic for the heart and the vasculature. Touyz and colleagues point out that hypomagnesemia predisposes people to “electrical irritability and arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, torsades des pointes, and long QT syndrome (de Baaij JH, et al. Physiol Rev. 2015).” It is also tied to endothelial dysfunction, increased vascular tone, and vascular fibrosis.

Wide Prevalence

The Touyz paper is a thorough synopsis of the state of the science on magnesium deficiency, its causes and mechanisms, its clinical impact, and the best strategies for detecting and remediating the problem (Touyz RM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2024).

Pharmaceuticals are only one potential cause of magnesium deficiency, but they are a very important one.

The authors acknowledge that the precise incidence of drug-induced deficiency is not really known. It’s not something for which practitioners are routinely screening, and in the published epidemiologic studies of the subject, there’s variability in diagnostic criteria and reporting methods. Objective numbers representing general populations are hard to come by.

That said, drug-related hypomagnesemia has a prevalence of between 7-11% in patients admitted to hospitals for any cause. Some estimates are as high as 20% among inpatients, depending on the population studied and the criteria used.

Mg deficiency is particularly problematic for the heart and the vasculature. Hypomagnesemia predisposes people to “electrical irritability and arrhythmias, including atrial fibrillation, torsades des pointes, and long QT syndrome.”

Among outpatients the estimate is that between 2% and 4% of all people are suffering from drug-induced magnesium depletion. This is likely an underestimate. But even if we assume that 4% is correct, that’s still 13.7 million Americans potentially at risk.

PPIs, Diuretics are Culprits

Among long-term PPI users, the prevalence is roughly 20%. That’s because PPIs alter the pH of the gut lumen, which adversely impacts intestinal magnesium absorption. This effect is both dose- and duration-dependent.

That’s a scary thought, given that nearly 25% of all adults worldwide are taking PPIs, according to a 2023 global study of prescription drug use. The US and other industrialized nations are clearly over-represented in this survey, but the general global trend is clear: PPIs are consistently among the top most prescribed drug classes (Shanika LGT, et al. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2023).

Diuretics are similarly problematic. Some researchers estimate between 25%-30% of people taking loop diuretics are magnesium-deficient. For those on thiazides, the estimates range between 25% and 30%. According to data gathered by biopharma industry analysts at IQVIA, there were roughly 82 million diuretic prescriptions in 2022.

Aminoglycoside antibiotics such as gentamycin can also cause magnesium wasting. Though antibiotic use in general has, thankfully, declined in recent years, they are still among the most widely prescribed pharmaceutical classes.

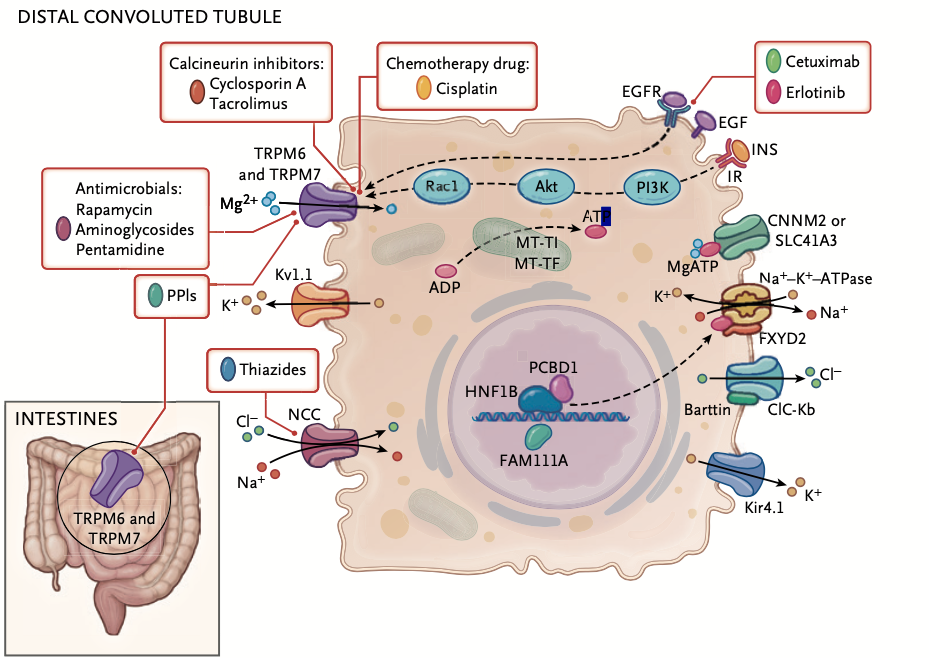

Dr. Touyz and co-authors note that, “Most cases of drug-induced hypomagnesemia are explained by renal magnesium wasting.” That means any drug that substantially impacts kidney function could lead to magnesium depletion. Calcineurin inhibitors, cisplatin, and EGF receptor (EGFR) antagonists such as cetuximab and erlotinib can also have deleterious effects on magnesium.

Cisplatin is especially problematic. Anywhere between 40% and 90% of people undergoing cisplatin chemotherapy will develop hypomagnesemia. Other red flag drugs include the antifungal amphotericin B, and antivirals like foscarnet.

Given the widespread prevalence of polypharmacy in most industrialized countries, many people could be taking two or more magnesium-wasting drugs simultaneously. This, of course, amplifies the risk.

Detecting Mg Deficiency

The standard approach to assessing magnesium status is simply to measure total serum magnesium. It’s a quick, inexpensive way to gauge short-term changes.

But keep in mind that the vast majority of the body’s total magnesium is intracellular. In fact, less than 1% of all magnesium is in circulation. Consequently, serum levels do not reliably reflect magnesium stores in the tissues.

Further, serum levels can be affected by a range of confounding factors such as hypoalbuminemia, hemolysis, and presence of anticoagulants in the sample tubes.

That said, serum measurements are really the only practical objective test fit for clinical use.

25%-30% of people taking loop diuretics are magnesium-deficient. For those on thiazides, the estimates range between 25% and 30%. According to data gathered by biopharma industry analysts, there were roughly 82 million diuretic prescriptions in 2022.

According to generally accepted guidelines, normal serum magnesium levels in healthy adults range from 1.7 to 2.4 mg/dl (0.7 to 1.0 mmol per liter). Hypomagnesemia is defined as levels below 1.7 mg/dl.

But don’t rely on serum levels in isolation, the authors warned. Look at blood measurements in the context of a patient’s overall health, symptom patterns, clinical history, diet and lifestyle.

“Most cases of drug-induced hypomagnesemia are explained by renal magnesium wasting.” That means any drug that substantially impacts kidney function could lead to magnesium depletion.

“Controlled depletion–repletion studies in metabolic units have shown that even though serum magnesium concentration may be normal, intracellular stores can be depleted. Therefore, the use of blood magnesium levels alone, without consideration of dietary magnesium intake and urinary loss, probably underestimates magnesium deficiency in the clinic.”

While extreme deficiency will usually make itself known through symptoms like muscle cramps, tremors, seizures, arrhythmias and palpitations, or metabolic changes like hypokalemia and hypocalcemia, bear in mind that most patients who are mildly hypomagnesemic, with levels in the 1.5-1.7 mg/dL range, will likely be asymptomatic. But this does not mean they’re not at risk.

Common in Diabetics

Pay close attention to patients who have diabetes. Touyz and colleagues point to several studies showing hypomagnesemia is common among type 2 diabetics (Oost LJ, et al. Diabetes Care 2021; Oost LJ, et al. Endocr Rev. 2023).

In this context, “Renal magnesium wasting and increased albumin binding in the blood are probably the causes of hypomagnesemia,” Touyz writes. “Insulin resistance results in decreased renal magnesium reabsorption and increased magnesuria.”

Also be aware that alcohol use is a factor in this equation. Magnesium depletion is the most common electrolyte abnormality associated with chronic heavy drinking.

“Underlying mechanisms include decreased magnesium intake in malnourished persons, increased gastrointestinal loss, and magnesuria due to alcohol-induced renal tubular damage.” Magnesium deficiency in heavy alcohol users is often associated with liver dysfunction, and it signals an overall poor prognosis.

Pay close attention to patients who have diabetes. Touyz and colleagues point to several studies showing hypomagnesemia is common among type 2 diabetics.

If a patient’s history, physical exam, symptom patterns, lifestyle, prescription drug use, and bloodwork lead you to suspect a serious magnesium deficiency, it may be worthwhile to order tests like 24-hour magnesium excretion, fractional magnesium excretion, and magnesium loading protocols, which can help you differentiate between renal and gastrointestinal magnesium loss, says Dr. Touyz.

Co-Deficiencies

Also be aware that magnesium deficiency is often accompanied by other nutrient and electrolyte deficiencies.

Hypokalemia is common in patients with hypomagnesemia and vice versa; the two deficiencies co-occur in 38% to 42% of patients (Whang R, et al. Arch Intern Med. 1992). Longstanding magnesium deficiency impairs repletion of cellular potassium, and it amplifies renal potassium loss by promoting potassium secretion in the collecting duct.

That said, refractory potassium repletion is sometimes linked to magnesium depletion. This is particularly true in people with congestive heart failure, those on cisplatin, and those taking diuretics, and it can only be corrected after the magnesium levels have been normalized (Huang CL, Kuo E. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007).

“The interplay between magnesium and potassium also involves activation of the Na+–Cl− cotransporter (NCC), which promotes sodium reabsorption,” says Touyz. “Sustained NCC down-regulation enhances distal Na+ delivery during states of hypomagnesemia, promoting kaliuresis and hypokalemia.”

That said, refractory potassium repletion is sometimes linked to magnesium depletion. This is particularly true in people with congestive heart failure, those on cisplatin, and those taking diuretics.

Low calcium levels are also linked to hypomagnesemia (Schlingmann KP, et al. Nat Genet. 2002; de Baaij JHF. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2023). That’s because magnesium deficiency suppresses the release of parathyroid hormone (PTH), which consequently decreases renal sensitivity to PTH, leading to reduced reabsorption of calcium in the kidney. This is something researchers proved more than 40 years ago (Rude RK, et al. J Clin Endocrin Metab. 1978). Again, when low calcium co-occurs with hypomagnesemia, it is nearly impossible to fix without first normalizing magnesium levels.

Restoring Magnesium Levels

Touyz and colleagues note that there are no clear and widely accepted treatment guidelines for reversing hypomagnesemia. “Approaches depend largely on the presence and severity of clinical manifestations. Mild hypomagnesemia is managed with oral supplements. Many magnesium preparations are available, and they have variable absorption rates.”

They contend that the most effectively absorbed forms are organic salts (citrate, aspartate, glycinate, gluconate, and lactate), rather than inorganic salts (magnesium chloride, carbonate, and oxide).

Diarrhea is a common side effect of oral magnesium supplementation, “which poses a challenge for oral replacement.” It is definitely something that patients need to be educated about.

Inulin, a plant-derived fructan polysaccharide that functions as a form of insoluble dietary fiber, has been reported to improve serum magnesium levels in patients with PPI-induced hypomagnesemia, through increased gastrointestinal magnesium absorption (Hess MW, et al. Aliment Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2016). Inulin has other side benefits, too: it is a prebiotic so it promotes a healthy gut microbiome, and there’s some evidence that it can reduce serum LDL levels.

END