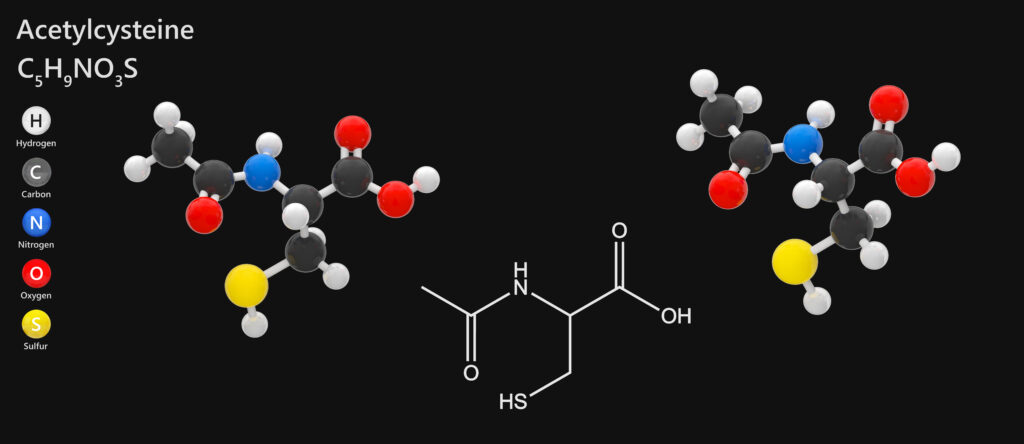

After nearly two years of contention, the Food and Drug Administration has signaled that it will not ban the use of N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) in dietary supplements. At the same time the agency refuses to reverse its steadfast position that NAC is a pharmaceutical ingredient which, by definition, excludes it from the supplement category.

This leaves the valuable antioxidant–derived from the naturally occurring amino acid L-cysteine–in a regulatory limbo that could persist for years to come.

In the summer of 2020, the FDA took the position that because NAC was approved in 1963 as an inhaled drug (Mucomyst) for obstructive lung disease, and again in 1985 as an oral drug (Acetadote) to mitigate acetaminophen toxicity, it cannot be legally permitted in supplements. That’s despite the fact that NAC supplements have been on the market for more than 30 years without incident.

FDA officials are standing by the view that NAC is a drug ingredient and not a supplement, but they’re reserving the option to maybe someday change their collective mind. In the mean time they’re probably not going to penalize companies that market NAC supplements

The supplement industry has been vociferous in challenging FDA’s attempt to categorically exclude NAC. Last June, the Council for Responsible Nutrition filed a Citizen Petition urging the FDA to reverse its stance, and to “revert to its longstanding policy of allowing manufacturers to market products containing NAC as dietary supplements” without obstruction.

The Natural Products Association (NPA) followed with a similar Citizen Petition in August, requesting that the FDA either determine that NAC is not excluded from the definition of supplements, or issue a special regulation explicitly permitting the lawful use of the ingredient in supplements, despite the prior drug approval.

Separately, NPA filed a lawsuit against the FDA in the US District Court in Maryland, seeking a permanent injunction against the FDA’s retroactive elimination NAC from the definition of dietary supplements.

Mixed Messages

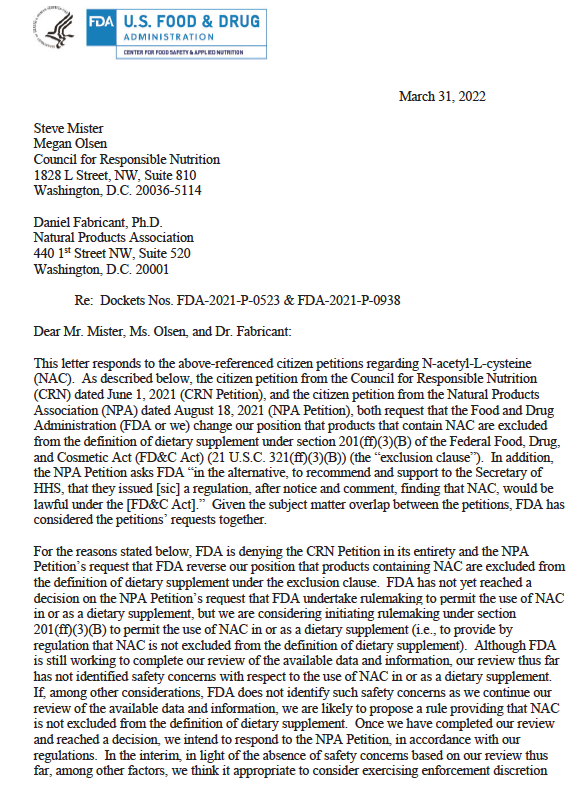

At the end of March, the FDA announced that it was denying the requests to reverse its stance on the exclusion of NAC.

However, the agency’s official statement indicates that FDA “has not yet reached a decision on the NPA citizen petition’s alternative request that the agency undertake rulemaking to allow the use of NAC in dietary supplements.”

The statement goes on to say that, “In the interim, in light of the absence of safety concerns based on our review to date, among other factors, the FDA is considering exercising enforcement discretion for NAC-containing products labeled as dietary supplements that would be lawfully marketed dietary supplements if NAC were not excluded from the definition of dietary supplement and are not otherwise violative of the FD&C Act.”

In other words, FDA officials are standing by the view that NAC is a drug ingredient and not a supplement, but they’re reserving the option to maybe someday change their collective mind. In the mean time they’re probably not going to penalize companies that market NAC supplements provided the products are true to their labels, not marketed as disease treatments, and not making false or misleading claims.

One month later, on April 21, the FDA issued a Draft Guidance on Enforcement Discretion for Certain NAC Products, in which the agency stated: “If, among other considerations, the FDA does not identify safety-related concerns as we continue our review of the available data and information, we are likely to propose a rule providing that NAC is not excluded from the definition of dietary supplement.”

If all of this sounds like a confused jumble of mixed signals, that’s because it is.

Ghost of Patents Past

The current NAC drama began in July 2020, when the FDA issued a flurry of warning letters to several companies marketing NAC as a hangover remedy. FDA charged that these companies A) made unlawful claims and B) were illegally selling a pharmaceutical ingredient mislabeled as a supplement.

In a rare move, these letters invoked the Drug Exclusion Provision within the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which states that a dietary supplement cannot contain:

- an article approved as a new drug

- an article authorized for investigation as a new drug, antibiotic, or biological for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted, and for which the existence of such investigations has been made public, which was not before such approval, certification, licensing, or authorization marketed as a dietary supplement or as a food.

In making the case for excluding NAC as a supplement, the agency cited a 60-year-old drug approval for an inhaled form the compound that was discontinued long ago.

FDA has tacitly permitted the sale of NAC supplements for decades. There are well over 1,100 non-Rx NAC products on the market, typically sold for liver health, detoxification, antioxidant activity, and immune system support. Many functional and naturopathic physicians also recommend NAC in their Covid management protocols.

There were 718 NAC-containing products on Amazon at the end of 2020; one year later, all were gone.

–Larisa Pavlick, United Natural Products Alliance

The ingredient is safe, even at high doses. There are many studies of NAC supplementation for diverse clinical problems in a wide range of patient subgroups. Adverse event rates are very low. Until the June 2020 warning letters, the FDA had no issues with NAC.

On their own, the warnings would have had little impact: the companies targeted are not major players, and the claims that NAC can prevent or cure hangovers are indeed questionable. FDA did not issue letters to companies selling NAC for other health purposes.

Amazon Swings the Axe

But in May 2021, Amazon announced that to comply with the FDA’s new position, it was eliminating all NAC-containing supplements from its digital shelves. Amazon’s move greatly amplified the impact of the FDA’s stance, given that for many supplement companies, Amazon accounts for 40%-60% of total sales.

According to Larisa Pavlick, VP of Global Regulatory & Compliance at United Natural Products Alliance (UNPA), there were 718 NAC-containing products on Amazon at the end of 2020; one year later, all were gone.

In November 2021, the FDA dangled hope that it might reverse course. The agency published a formal request for “information on the earliest date that NAC was marketed as a dietary supplement or a food, the safe use of NAC in products marketed in dietary supplements, and any safety concerns.”

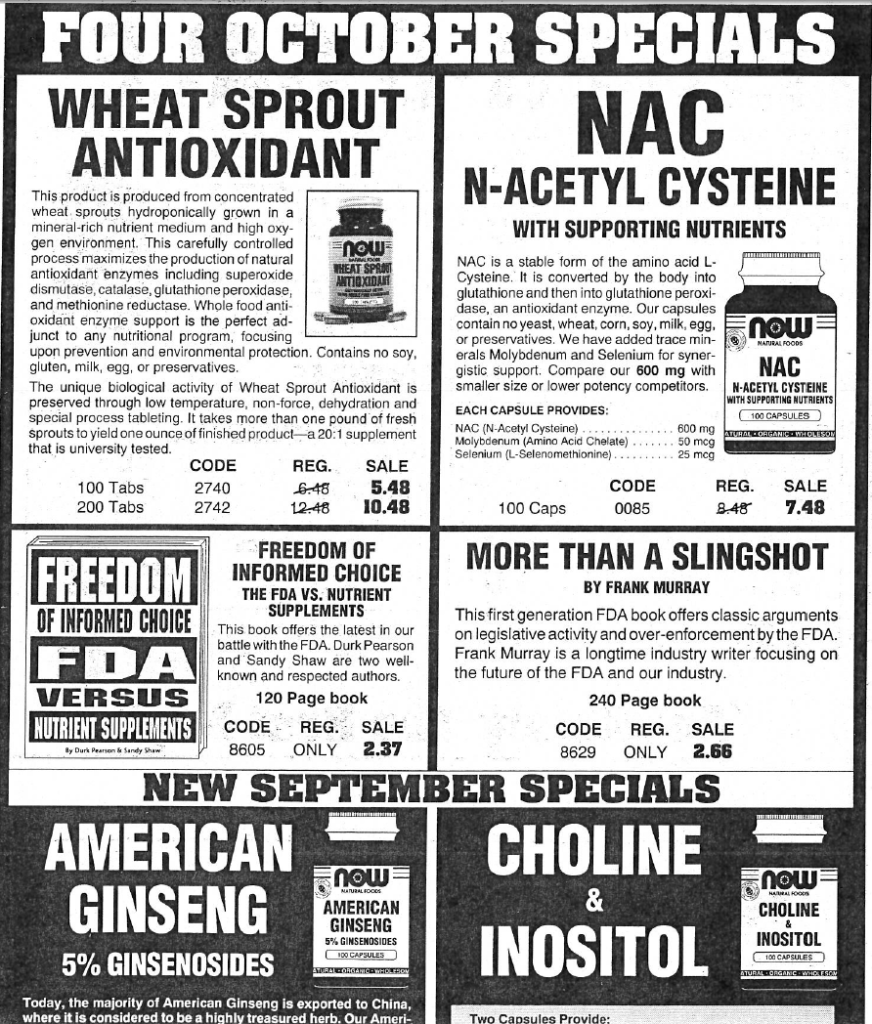

Industry trade groups put considerable effort into making a case that NAC should be grandfathered as an “old” dietary ingredient, since it was in wide use prior to the 1994 passage of the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), which formally defined what can and cannot be used in this product category.

Long History of Safe Use

The industry’s position, expressed via comments on an FDA docket, is that a retroactive application of a drug exclusion based on obsolete patents constitutes an unfair restriction of trade.

Pavlick and the UNPA coordinated with CRN, the American Herbal Products Association, and a long list of concerned stake-holders to assemble a NAC working group that quickly sorted through “warehouses, boxes, and basements for old paper records, and through antiquated software systems to provide a significant collection of pre-DSHEA records,” said UNPA President, Loren Israelsen.

The working group amassed old nutrition catalogs, spec sheets, lab testing data, freight bills indicating interstate commerce, old product labels with pre-’94 expiration dates, and print ads—some going back to the 1980s– for non-prescription NAC from Allergy Research Group, Pure Encapsulations, NF Formulations, Tyler, and Thorne Research, among other companies.

Despite the ample evidence that non-prescription NAC has been widely and safely used since well before DSHEA, the FDA opted to maintain its position that the ingredient should be excluded from the supplement category.

The American Association of Naturopathic Physicians, representing the nation’s NDs and NMDs, joined the effort. Based on 126 survey responses, AANP notes that naturopaths have routinely used NAC since at least 1990, with literature citations dating back to the early 1970s.

Despite the ample evidence that non-prescription NAC has been widely and safely used since well before DSHEA, the FDA opted to maintain its position that the ingredient should be excluded from the supplement category.

FDA Unconvinced

In a 25-page response to CRN and NPA, FDA Deputy Director for Regulatory Affairs Douglas Stearn, systematically dismantles the industry’s key arguments.

“The legislative history indicates that Congress believed that allowing an article to be marketed as a dietary supplement after it had been first approved or studied as a drug would not be fair to the pharmaceutical company that brought, or intends to bring, the drug to market; would serve as a disincentive to the significant investment needed to gain FDA approval of new drugs; and would enable manufacturers to escape appropriate safety and efficacy review and FDA oversight by being classified as dietary supplements,” Stearn writes.

The fact that the original 1963 patent for NAC was as an inhaled drug that was discontinued long ago does not change the fundamental principle, in FDA’s view.

Likewise, the industry’s proof that non-Rx NAC was widely sold before DSHEA formally defined what could and could not be sold as supplements, does not obviate the original drug patent nor the FDA’s prerogative to apply an exclusion at will.

The Cholestin Precedent

Such an exclusion is not without precedent.

Stearn cites Pharmanex v Shalala, a contentious 2001 case in which a US Court of Appeals ruled that the FDA had the right to prohibit a company called Pharmanex from marketing its Cholestin red yeast rice as a supplement. Cholestin’s active compound—monacolin K—was identical to lovastatin which was approved as a cholesterol-lowering drug (Mevacor) in 1987.

Red yeast rice—a form of rice fermented with the mold Monascus purpureus–is considered a traditional Asian food that also has a long history of use in Chinese medicine to aid digestion and invigorate the blood. The FDA contended that Pharmanex was deliberately manufacturing its product to contain high levels of the statin compound, and marketing it for its cholesterol-lowering benefits, yet selling it as a dietary supplement.

“Cholestin was excluded from the dietary supplement definition under the exclusion clause because the approval of Mevacor as a new drug preceded Pharmanex’s marketing of lovastatin as a dietary supplement,” wrote Stearn.

FDA’s ban on Cholestin and other high-monacolin A products remains in effect to this day. That said, red yeast rice products are still available online and in stores; most have low monacolin-K levels, and they avoid making lipid-lowering claims.

Industry leaders are rightly concerned that FDA’s exclusion of NAC sets the precedent for the curtailment of many other supplement ingredients such as L-carnitine, niacin, and CBD, which are currently available in supplement as well as prescription form. Some herbs currently sold as supplements are also the sources of prescription drugs, and could potentially be nixed as supplements.

New NAC Drug Trials

Many supplement advocates believe that in targeting NAC, the agency is doing the bidding of drug companies, paving the path for new NAC-based pharmaceuticals.

There are currently 19 clinical studies of NAC for COVID care in the government’s Clinical Trials registry, including several looking at NAC-based drugs. This includes a high-profile study now underway at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center involving 84 high-risk patients with COVID, treated with inhaled or IV NAC. This trial is slated for completion in May 2023

Last year, a company called Orpheris—a division of Ashvattha Therapeutics— ran a phase 1 open-label clinical study of subcutaneous injections of “OP-101,” a Dendrimer N-acetyl cysteine. The company’s long-term vision for OP-101 is to develop it as a drug for childhood cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy (ccALD). The company also plans to “investigate the potential of OP-101 in other neurological diseases,” particularly Parkinson’s and aymyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Industry leaders are rightly concerned that FDA’s exclusion of NAC sets the precedent for the curtailment of many other supplement ingredients such as L-carnitine, niacin, and CBD, which are currently available in supplement as well as prescription form.

One comment filed on the FDA’s NAC docket does indicate that pharma companies see prior drug exclusion as a viable strategy for clearing the field of supplement competition.

John Gold, PhD, Vice President of Emmeria, a privately-held drug company, writes that his company is “the sole sources of EMM-737, EMM-738, EMM-739 and EMM-740, Emmeria’sproprietary form of trimethylglycine, astragaloside, ellagic acid and berberine, which have been studied as new drugs and for which substantial clinical investigations have been instituted.

“We request that FDA take the preclusion provision of Section 201(ff) of the Federal, Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act seriously to protect the right of companies that have spent significant time and research to develop drugs products from competition from dietary supplements that are clearly new dietary ingredients that have never filed a new dietary ingredient notification prior to the institution of substantial clinical trials.”

A Regulatory Conundrum

Regardless of the motivations, the contention over NAC has put the FDA in a difficult situation:

If the agency takes a hardline stance and bans all NAC supplements, it will be rightly criticized for unnecessarily restricting access to a harmless, effective, and inexpensive self-care modality in the middle of a pandemic, for no discernable public health reason, and in the absence of harm.

If FDA backtracks and issues a new special rule that exempts NAC from the prior drug exclusion and formally permits its use in supplements, it risks looking indecisive. This would also dilute the future power of the prior drug exclusion clause as a means of enforcing a hard boundary between prescription drugs and supplements.

Given these options, the FDA’s recent mixed messages about NAC are understandable.

After more than a year without a leader, FDA now has a new commissioner following the February 15 confirmation of Robert Califf, MD. Over the course of his career, Califf has said surprisingly little about supplements, so his overall attitude toward them is not yet known. Whether Califf’s presence at FDA will shift the agency’s position on NAC—and if so, in what direction—also remains to be seen.

Holistic medical professionals, their patients, and the nutraceutical companies that serve them have much to lose—or to gain—in the outcome of this peculiar situation.

END