In recent years, microbiome researchers have uncovered a wealth of new information about how beneficial microbes promote fertility, pregnancy, and  postnatal child health, all of which suggests that probiotics should become a routine part of prenatal healthcare.

postnatal child health, all of which suggests that probiotics should become a routine part of prenatal healthcare.

Friendly microorganisms provide support for a normal healthy immune system and genitourinary tract, and help to relieve symptoms of infectious lactational mastitis and gastrointestinal disturbances, while modulating the infant immune system to improve defense mechanisms and decrease infant atopic dermatitis and eczema risk.1-12

The effects can be profound for both mother and child. In one study, maternal use of probiotics during pregnancy reduced the risk of childhood allergic disease by half!

Probiotics exert a plethora of local and systemic health benefits to the host. They positively influence digestive health, synthesize health-promoting short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), improve microbial balance, maintain intestinal integrity and enhance sIgA release. Their immune-regulatory influence supports a normal healthy immune system, and dampens inflammatory and allergic responses.

Researchers have long known that organisms living in the vaginal tract, and in breast milk influence the establishment of an infant’s gut microbiome. Absence of exposure to these organisms is one reason why infants born via C-section, and those who are not breastfed, tend to be predisposed to colic and other gastrointestinal disturbances.

A recent wave of research is showing just how important breast milk is in establishing a baby’s microbiome.

Entero-Mammary Transfer

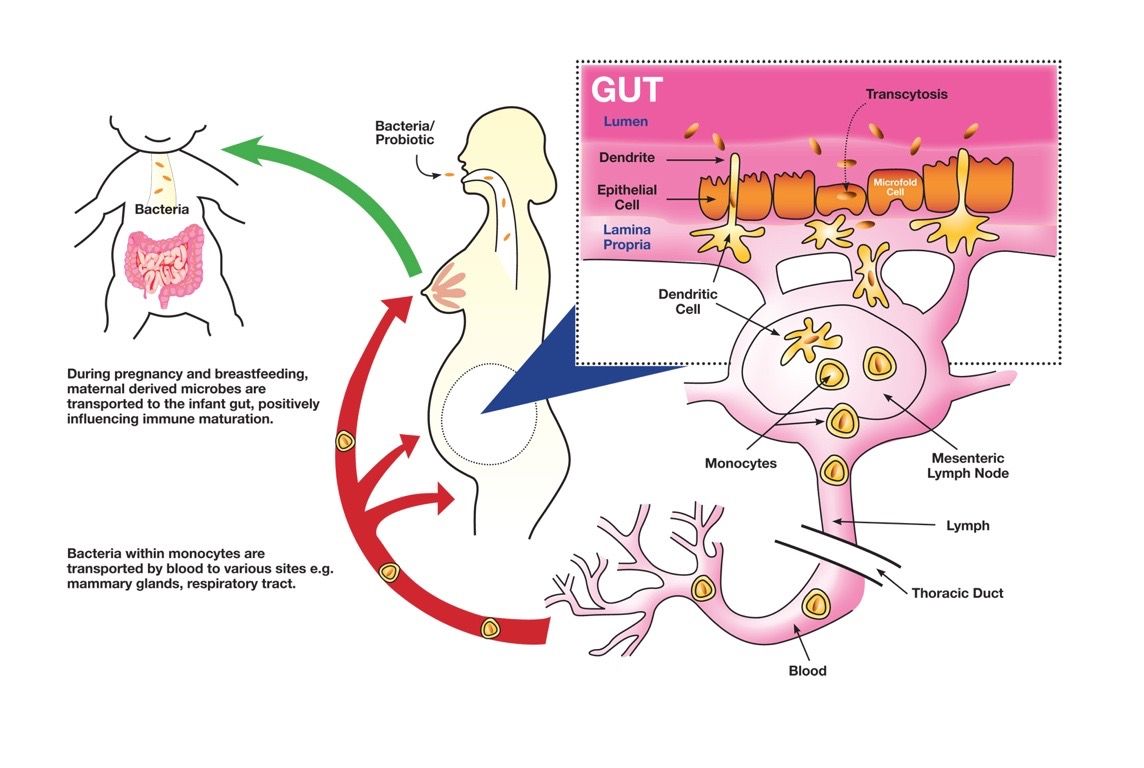

There is a direct connection between the organisms in a mother’s gut and those in her milk. An ongoing process of systemic translocation occurs, where intestinally derived components (including probiotics and their DNA signatures) are carried by monocytes to other areas of the body.3,4 Transport from the GI tract to the lactating breast is known as the “entero-mammary pathway”.

In other words, beneficial microbes are actively transported from a woman’s GI tract to her breasts, and then into her child’s GI tract via the milk. The entero-mammary transport process is upregulated by the hormone cascades associated with pregnancy and lactation.

Organisms in breastmilk contribute greatly to the establishment of infant commensal communities and maturation of infant immune systems.

Translocation is not limited between the GI tract and lactation glands. Further findings that defy our past beliefs are the discovery of probiotic organisms within amniotic fluid, the placenta and meconium (first stool) of neonates.5 This is an a incredible revelation, one that runs counter to past literature describing the infant GI tract as sterile prior to delivery.

Translocation is not limited between the GI tract and lactation glands. Further findings that defy our past beliefs are the discovery of probiotic organisms within amniotic fluid, the placenta and meconium (first stool) of neonates.5 This is an a incredible revelation, one that runs counter to past literature describing the infant GI tract as sterile prior to delivery.

These findings have huge implications for the use of probiotics throughout pregnancy. Most recently, research suggests that these transported probiotics begin the process of foetal immune maturation much earlier than previously thought.

A trial of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Bifidobacterium lactis given to pregnant women illustrated this. The probiotic treatment significantly modulated factors related to innate immunity (e.g. the expression of TLR-related genes), both in the placenta and in the fetal gut.5 Probiotic intake during pregnancy and lactation has the potential to positively influence a child’s immune system.

The potential health benefits can be profound.

Quelling Atopic Dermatitis

Probiotics consumed during pregnancy and lactation (for up to six months), markedly decrease the incidence of atopic dermatitis and eczema in the first (two-seven) years of children’s lives.6The key strains studied here include L. rhamnosus and B. lactis.

Atopic dermatitis is very common among infants and small children, and causes significant discomfort, compromised sleep patterns (for children) and parents alike) and interference with other aspects of life. Given that roughly 40% of all children will develop asthma, this clearly an issue to be taken seriously.

Stool samples from infants and children with atopic eczema have significantly less lactobacilli and bifidobacteria than samples from healthy kids. Improving colonization of these microbes hence reduces the risk of AE development via various mechanisms.

Lactic acid-producing bacteria improve intestinal integrity, reducing the increased leakage of allergens from the intestine. As discussed, probiotics also modulate immune responses to allergens. They do this by shifting the balance in the immune system, increasing regulatory T cell release, thus reducing Th2 cytokines and resultant IgE levels. This influences phagocytosis, secretion of sIgA and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines.7,8

It is important to note that infants are naturally born in a Th2-dominant state, and they produce a lot of IgE. Thus they are innately predisposed to allergic reactions via mast cell activation. Early exposure to organisms like L. rhamnosus and various species of Bifidobacteria will reverse this Th2 bias, and promote IgA production which promotes allergen exclusion and reduces exposure of the baby’s immune system to antigens.

During pregnancy, there is an increased risk of certain conditions such as urinary tract infections, digestive disturbances and thrush.9Each of these conditions is associated with local dysbiosis and compromised mucosal immunity. Probiotic therapy with lactobacilli can improve urogenital health via immune modulation, pathogen displacement and creation of an environment less conducive to proliferation of pathogens.9-11

Reversing Mastitis

Given what we know about the importance of breastfeeding for all aspects of infant health, it is essential that we do all we can to help new mothers avoid complications, such as mastitis, which may compromise her ability, or desire, to breastfeed.

Mastitis affects up to 33% of lactating mothers, and represents a significant cause of early weaning. Lactational mastitis is an inflammation of the lobules in the mammary gland. It usually presents with an infectious origin, but additional factors such as insufficient draining of the breast and poor attachment will contribute significantly also.

Staphylococcus aureus and S. epidermidis are considered the main etiological agents of acute and chronic mastitis respectively.1,2 Each of these  species exhibits multi-drug resistance, making these infections difficult to treat.1 This knowledge has motivated researchers to search for alternative methods to prevent and provide symptomatic relief of mastitis during breastfeeding.

species exhibits multi-drug resistance, making these infections difficult to treat.1 This knowledge has motivated researchers to search for alternative methods to prevent and provide symptomatic relief of mastitis during breastfeeding.

Spanish scientists isolated two probiotic strains present in the breast milk of healthy mothers: L. salivarius and L. gasseri. Women with lactational mastitis had almost undetectable levels of these beneficial lactobacilli, paired with high levels of pathogenic staphylococcal species.1

In short, lactational mastitis seems to correlate with dysbiosis. In general, loss of GI microbial diversity increases the risk of overgrowth of group B streptococci.

What if we could correct this imbalance?

A small cohort of 20 breastfeeding women with mastitis were divided into two groups, a probiotic treatment group (receiving a combination of L. salivarius and L. gasseri) and a control group. All women in the study had used prescription antibiotics with no relief.

After a period of 14 days, the probiotic treatment group showed no signs of lactational mastitis, whereas the condition persisted in those of the control group.1 These results showed probiotic therapy to be effective where antibiotics had failed.

In a larger study involving 352 women with lactational mastitis, treatment with L. salivarius or L. fermentum (also found in the breast milk of healthy women), produced greater symptom improvement when compared to current standard therapy, and a lower recurrence of mastitis.2

Probiotics & Fertility

Simply put, dysbiosis—the overgrowth of unfriendly gut organisms—compromises fertility in women. One reason for this is that dysbiosis and leaky gut lead to chronic systemic inflammation, which in turn increases aromatase activity. Systemic inflammation also compromises luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). The net result is widespread hormone dysregulation and reduced fertility.

It is notable that irritable bowel syndrome—a condition clearly associated with dysregulation of the gut microbiome—is associated with increased risk of miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy.

Long-term use of oral contraceptives—especially hormonal combinations—substantially alter the vaginal microbiome, and this can compromise fertility long after a woman has stopped using the contraceptive.

While there are no definitive trials showing that probiotic treatment can improve fertility or reverse infertility, it is certainly worth considering given the widespread inflammation-modulating benefits it can give. At the very least, women who are discontinuing oral contraceptive use and who want to become pregnant should consider taking a broad-spectrum, multi-strain probiotic for a few months.

The health benefits of probiotics –especially those rich in Lactobacillus species–for reproductive-age women are many. There are studies indicating that they can be effective in preventing genitourinary infections, which in turn would reduce the risk of pre-term labor. They can attenuate the risk of diabetes and obesity in both mother and child, and they also reduce risk of depression and mood disorders for both mother and child.

Pregnant women who take probiotics regularly are less likely to experience constipation—a common, unhealthy, and extremely uncomfortable condition.

For all these reasons, probiotics should be carefully considered for most, if not all women during pregnancy and lactation. The research is strong; it simply needs to be implemented.

For more health articles, go to www.bioceuticals.com.au/education/articles

Belinda Reynolds, BSc Nut&Diet (Hon) is a world-renowned dietitian with a special interest in women’s health, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Based in Sydney, Australia, Belinda graduated with an Honours Degree in Nutrition and Dietetics from the University of Wollongong in 2003. She has been involved in the complementary medicine industry for nearly 15 years, and currently serves as Education Manager for FIT BioCeuticals. Outside of this Belinda has spent time working in hospitals and lectured at the Australasian College of Natural Therapies.

References

1.Jiménez E, Fernández L, Maldonado A, et al. Oral administration of Lactobacillus strains isolated from breast milk as an alternative for the treatment of infectious mastitis during lactation. Appl Environ Microbiol 2008 Aug;74(15):4650-5.

2.Arroyo R, Martín V, Maldonado A, et al. Treatment of infectious mastitis during lactation: antibiotics versus oral administration of Lactobacilli isolated from breast milk. Clin Infect Dis 2010 Jun 15;50(12):1551-8.

3.Fernández L, Langa S, Martín V, et al. The human milk microbiota: Origin and potential roles in health and disease. Pharmacol Res 2012 Sep 10. pii: S1043-6618(12)00165-X. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2012.09.001. [Epub ahead of print]

4.Perez PF, Doré J, Leclerc M, et al. Bacterial imprinting of the neonatal immune system: lessons from maternal cells? Pediatrics 2007 Mar;119(3):e724-32.

5.Rautava S, Collado MC, Salminen S, et al. Probiotics modulate host-microbe interaction in the placenta and fetal gut: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neonatology 2012;102(3):178-84.

6.Doege K, Grajecki D, Zyriax BC, Detinkina E, Zu Eulenburg C, Buhling KJ. Impact of maternal supplementation with probiotics during pregnancy on atopic eczema in childhood–a meta-analysis. Br J Nutr 2012 Jan;107(1):1-6.

7.Michaelsen KF. Probiotics, breastfeeding and atopic eczema. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 2005 Nov;(215):21-4.

8.Betsi GI, Papadavid E, Falagas ME. Probiotics for the treatment or prevention of atopic dermatitis: a review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Dermatol 2008;9(2):93-103.

9.Li J, McCormick J, Bocking A, et al. Importance of vaginal microbes in reproductive health. Reprod Sci 2012 Mar;19(3):235-42.

10. Reid G, Dols J, Miller W. Targeting the vaginal microbiota with probiotics as a means to counteract infections. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2009 Nov;12(6):583-7.

11. Reid G. Probiotic and prebiotic applications for vaginal health.Review. J AOAC Int 2012 Jan-Feb;95(1):31-4.

12. de Milliano I, Tabbers MM, van der Post JA, et al. Is a multispecies probiotic mixture effective in constipation during pregnancy? ‘A pilot study’. Nutr J 2012 Oct 4;11:80. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-11-80.