Gastrointestinal inflammation is a common sequela of traumatic brain injury, and it can lead to a breakdown of intestinal barrier function and a vicious cycle of chronic inflammation along the brain-gut axis.

vicious cycle of chronic inflammation along the brain-gut axis.

Given the intimate connection between the brain and the gut, it makes strong clinical sense to look closely at gut function in any patient who has suffered a significant head injury.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) can occur in anyone at any time. A car accident, a slip and fall on a slick floor, an impact sustained during a contact sport, are all scenarios in which a TBI is possible.

A blow to the head should never be ignored; TBIs are serious, multifactorial conditions with ramifications far beyond the brain.

Immediately following a head injury, or in the weeks shortly after, a patient may experience a variety of symptoms, such as headache, vomiting, lethargy, or changes in mood. In reality, TBI can also have long-term effects on the musculoskeletal system, the gastrointestinal tract and the immune system. In some cases, these symptoms only emerge months after the actual injury.

Assessing and treating TBI requires more than just brain work; it requires careful assessment of all organ systems, especially the gut.

The brain-gut aspect of TBI has received considerable attention from researchers, medical thought-leaders, and even from bloggers writing for lay audiences online. But given the time pressures of day-to-day clinical practice, it is often overlooked.

A Pathogenic Wave

Putting it in the simplest of terms, there is a pathogenic wave that flows from the brain to the gut. Following a head injury, the brain itself becomes inflamed. That seems obvious. What’s not is obvious is the fact that this leads to inflammation in the gut (Bansal V, et al. J Neurotrauma. 2009; 26(8):1353-1359.)

This actually happens very quickly. Within hours, a TBI causes detrimental changes in the permeability of intestinal mucosa (Hang C-H et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2003; 9(12):2776-2781.

Inflammation in the gut increases intestinal permeability, which allows for the cascade of large, immunogenic, dietary proteins and bacterial toxins into the bloodstream. Systemic inflammation follows. This perpetually keeps the blood-brain barrier (BBB) open and fuels the inflammation in the brain (Kharrazian D. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015; 21(Suppl 3):28-32.)

A compromised blood-brain barrier allows the entry of circulating immunogens into the brain and nervous system, fueling the neurological inflammation. In a sense, both the brain and the gut are “on fire” following TBI.

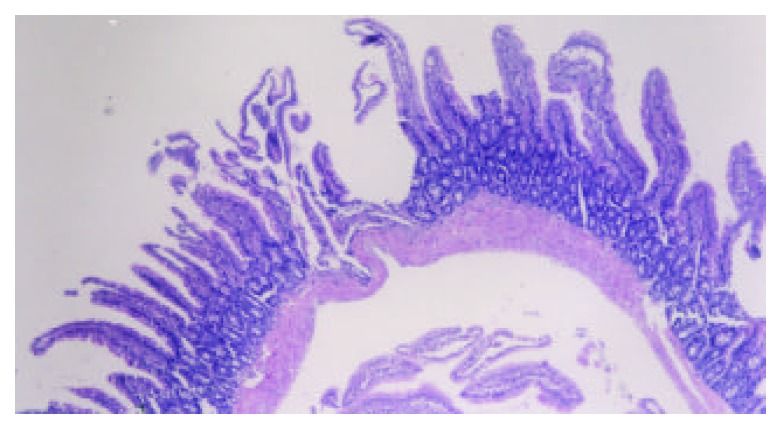

The intestinal mucosa can become very disordered following TBI. Bansal showed that intestinal villi–the means by which the body absorbs nutrients–are destroyed after TBI. This can compromise a person’s overall nutritional status, which often has disproportionate impact on the brain, seeing as it is the most nutrient-dependent, toxin-vulnerable organ in the body.

The intestinal mucosa can become very disordered following TBI. Bansal showed that intestinal villi–the means by which the body absorbs nutrients–are destroyed after TBI. This can compromise a person’s overall nutritional status, which often has disproportionate impact on the brain, seeing as it is the most nutrient-dependent, toxin-vulnerable organ in the body.

A broken intestinal barrier allows for bacterial toxins such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and distending toxin-B (CdtB), and immunogenic dietary proteins, such as lentil lectins and agglutinins from wheat and beans to cross into the bloodstream. That can be bad news for the nervous system. Lectins and agglutinins may bind to myelin, and gluten and dairy antigens can generate antibodies that cross-react with neurological tissues. (de Punder K and Pruimboom L. Front Immunol. 2015; 6:223).

Assessing Gut Integrity Post-TBI

It is clear that the intestinal barrier must be intact for the prevention of disease (Konig J, et al. Clin Translational Gastroenterol. 2016; 7:e196)

How can we know if the intestinal barrier is intact after a TBI? We can test for it!

Basic intestinal barrier permeability testing must include assessments of both paracellular (tight junction) and transcellular (epithelial cell) pathways.

Serum immunoglobulin testing is preferred to other methods. Intestinal epithelial cell damage can be assessed by measuring IgA against the actomyosin network. Do not look for Actomyosin IgG, as this may be elevated due to extra-intestinal smooth muscle damage. Intestinal tight junction breakdown shows up via antibodies to occluding proteins (aka tight junction proteins) and zonulin.

For advanced intestinal permeability testing, look at serum antibodies to cytoskeletal proteins (alpha-actinin, vinculin and talin), which control the tight junctions. If these are elevated, it indicates that epithelial cells are breaking down and that tight junctions are no longer functioning properly. Intestinal breakdown happens at both the paracellular and transcellular levels, and this simple blood test provides a more thorough, clinically relevant look at the integrity of the intestinal barrier.

Note that a lactulose/mannitol test, though simple, will not provide enough clinical information about what is happening with regard to the intestinal barrier function (Jakobsson I, et al. Gut. 1986; 27(9):1029-1034.).

Similarly, zonulin tests are not especially helpful in this context, because zonulin levels drastically fluctuate over the course of any given day (Vojdani A, et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2017; 23(31):5669-5679).

Due to the highly inflammatory nature of bacterial toxins, it is very important to assess serum antibodies to things like lipopolysaccharides and other toxins.

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are endotoxins from gram-negative bacteria. The presence of antibodies to LPS indicates gut dysbiosis and systemic infiltration by LPS.

For advanced bacterial toxins assessment, add a test for distending toxin-B (CdtB), a substance released by Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter jejuni. CdtB, although less common than LPS, it is ten times more inflammatory. If bacterial toxins are entering the blood stream, their inflammatory effect can perpetually keep the blood-brain barrier open, which puts the entire nervous system at risk.

Preventing Long Term Damage

It is important to test thoroughly. If you test only for tight junction integrity, you will miss patients who have epithelial cell damage.

The tests outlined here are the tests I use with my patients in my own clinical practice. They are all available from Cyrex Laboratories.

By knowing what structures are breaking down, you can tailor gut-healing protocols that match each patient’s needs. Being that bacterial toxins, LPS and CdtB, are involved in systemic inflammation and breaking of the BBB, it is important to know whether or not gut dysbiosis needs to be addressed in these cases.

The window of opportunity to prevent neurological disorders is relatively short. Environmentally induced neuro-autoimmunity can occur within 5 years from the onset of BBB permeability. The entry of environmental immunogens into delicate neurological tissues can be very problematic over the long term.

In any patient who’s sustained a TBI, test the intestinal barrier at once. Delays in identifying the cyclic pathogenic mechanisms triggered by TBI result in greater neurological tissue damage and decreased quality of life. Early detection is the key for a better outcome.

END

Robert G. Silverman, DC, DACBN, CCN,is a chiropractic doctor, clinical nutritionist and author of, “Inside-Out Health: A Revolutionary Approach to Your Body,” an Amazon No. 1 bestseller in 2016. He maintains a busy private practice, Westchester Integrative Health Center, which specializes in the treatment of joint pain using functional nutrition along with cutting-edge, science-based, nonsurgical approaches. The ACA Sports Council named Dr. Silverman “Sports Chiropractor of the Year” in 2015. Dr. Silverman is also on the advisory board for the Functional Medicine University. He is a frequent contributor to journals and publications including Integrative Practitioner, MindBodyGreen, Muscle and Fitness, The Original Internist and Holistic Primary Care. Reach Dr. Silverman at: 914.287.6464; email: info@DrRobertSilverman.comwww.DrRobertSilverman.com