When Dr. Terry Wahls first began speaking about how she had reversed her own case of multiple sclerosis using nutritional and lifestyle interventions, she was quite literally banned by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society.

Sclerosis Society.

The organization would not let her present at its symposia.

“They told me I was creating false hope,” said Dr. Wahls, at the Institute for Functional Medicine’s 2018 annual international conference. “My colleagues were saying, ‘Be careful how you talk about this.’ Everyone was so afraid. So, I learned how to document everything very, very carefully.”

Wahls, Assistant Chief of Staff at Iowa City Veterans Administration medical center, and clinical professor of medicine at the University of Iowa, is the first to admit she’s making bold claims.

In asserting that a comprehensive lifestyle protocol centered on a strict Paleo diet can alter the course of MS, Wahls is challenging long-held medical axioms: that MS is irreversible; that motor or cognitive function once lost is lost forever; that diets are at best, “adjunctive,” but never truly therapeutic. She well understands the reflexive disbelief shown by her medical colleagues.

But her own life—and the lives of roughly half of all MS patients she has treated—provide clear evidence that all of those assumptions are wrong.

Like Dr. Dale Bredesen has done with Alzheimer’s, Wahls is showing that MS need not always be a one-way ticket to severe disability. In many cases, progression can be stayed. In some, it can be reversed. Moreover, diet, nutraceuticals, detoxification, and exercise can sometimes achieve what drugs cannot. Far from peddling “false hope,” Wahls offers real outcomes and meaningful solutions.

Walking Her Talk

In the truest sense, Terry Wahls “walks her talk.” But 15 years ago, she was barely walking at all.

A fifth-generation Iowan, Wahls grew up on a family farm, and was always active. She loved Tae Kwon Do, and was once a national champion. But life in an agricultural community meant early and frequent exposure to pesticides and herbicides, which she believes were a contributing factor in her illness.

“I received the very best care possible. I took the recommended chemotherapy. I was taking the latest, newest drugs. I took Tysabri and then CellCept. Still, by 2003, my disease had transitioned to secondary progressive MS…. “Conventional medicine was not going to stop my slide into a bed-ridden and demented life.”

–Terry Wahls, MD

She completed medical school at the University of Iowa, had two children, and was well along in her internal medicine career when, in 2000, she was diagnosed with MS.

As a physician she knew the prognosis.

“I knew that within 10 years of diagnosis, one third of all patients will have difficulty walking, will need a cane, walker, or wheelchair. Half will be unable to work because of profound fatigue. I had two children. I was the main breadwinner for our family. I could not let that happen.”

She sought care at the Cleveland Clinic and saw top neurologists. “I received the very best care possible. I took the recommended chemotherapy. I was taking the latest, newest drugs. I took Tysabri and then CellCept. Still, by 2003, my disease had transitioned to secondary progressive MS (SPMS),” she recalled in a landmark 2011 TED Talk viewed by more than 3 million people.

By November 2007, despite everything conventional medicine had to offer, Wahls’ health was in rapid decline. She was reliant on a tilt-recline wheelchair, and could only walk short distances using two canes. She kept losing her keys, and her phones. She knew her cognitive function was deteriorating, and feared losing her clinical privileges.

Her doctors said the disease had progressed to a point where there are no spontaneous remissions, and she would never regain lost function. “Conventional medicine was not going to stop my slide into a bed-ridden and demented life.”

Self-Experimentation

But she also knew that researchers were shedding new light on the immunology and biochemistry underlying neurodegenerative diseases. She dove into the literature.

“Brains afflicted with MS shrink over time. I went every night to read the latest research on other diseases in which brains shrank: Huntington’s, Parkinson’s, and Alzheimer’s. I saw that in all three the mitochondria do not work well. And I found mouse studies in which mitochondria had been protected using fish oil, creatine, and CoQ10. So I translated the mouse-sized doses into human sized ones, and began my first round of self-experimentation.”

That initial foray into nutraceutical self-intervention slowed progression. Though it did not arrest or reverse the disease, it was enough to encourage Dr. Wahls to continue exploring. Then, she discovered the Institute for Functional Medicine’s advanced practice module on Neuroprotection.

Functional medicine gave Wahls a framework for understanding MS as a disease of inflammation, autoimmunity, and cellular energy dysfunction. More importantly, it gave her a map for identifying modifiable disease drivers.

To be sure, there is a genetic component to MS. Roughly 100 genes that have been identified (so far) that increase risk. If you have one parent or primary relative with MS your risk increases 3-5%. If you have two parents with MS, the risk rises to 30%. But like so many chronic, degenerative conditions, diet and lifestyle factors exert at least as much influence as genetics, if not more.

Minding Myelin & Mitochondria

MS is, fundamentally, a condition of demyelination and mitochondrial dysfunction.

In order to make myelin, the brain needs a lot of B vitamins, in particular B1 (thiamine), B9 (folate) and B12 (cobalamine). It also needs a lot of omega-3 fat and iodine (Bourre JM. J Nutr Health Aging 2006; 10(5)377-85). Sulfur and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) are essential for making neurotransmitters.

In order to make myelin, the brain needs a lot of B vitamins, in particular B1 (thiamine), B9 (folate) and B12 (cobalamine). It also needs a lot of omega-3 fat and iodine (Bourre JM. J Nutr Health Aging 2006; 10(5)377-85). Sulfur and vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) are essential for making neurotransmitters.

Dr. Wahls started taking supplements, but also tried to get as many of these nutrients as possible from food. “I was able to design a food plan specifically for my brain and my mitochondria”

The core of Wahls’ therapeutic lifestyle, which she detailed in her popular 2014 book, The Wahls Protocol, is a modified Paleo diet very high in vegetables, grass-fed meat and wild fish, and largely free of grains, dairy and starches. The diet is augmented with targeted nutraceuticals that improve mitochondrial function and promote production of myelin and neurotransmitters.

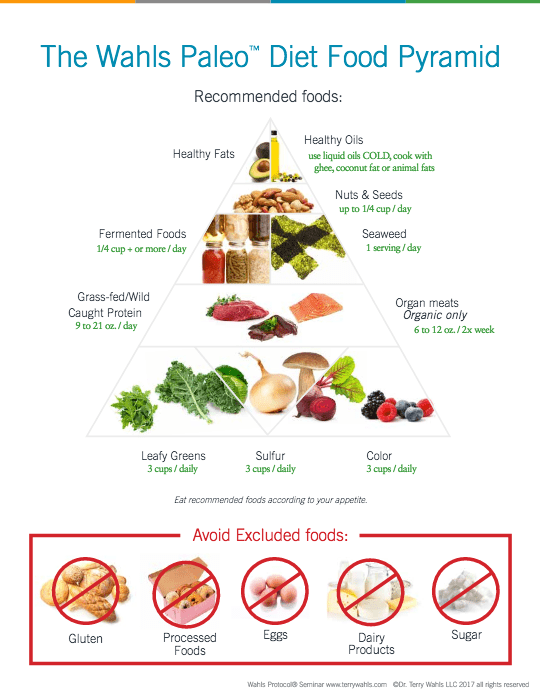

The Wahls diet is a three-stage process:

- Stage One: Eliminate dairy and gluten; Eat 3 cups daily of green leafy vegetables (kale, parsley, collard greens, chard, etc); 3 cups of sulfur-rich vegetables (broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, turnips, rutabaga, radishes, garlic, onions, shallots, chives, and mushrooms); and 3 cups of brightly colored fruits and vegetables (berries, beets, peppers, carrots, yellow/orange squashes, etc). Switch to organic, grass-fed meats, and only wild-caught ocean fish.

- Stage Two: Maintain the 9 cups of veggiess and fruit per day. Cut non-glutinous grains, legumes, and potatoes to no more than twice per week; Introduce algae, seaweed, and organ meats; Add in probiotic foods.

- Stage Three: Shift intake to be as low-carb and high-fat as possible; Eliminate all grains, legumes, potatoes; Decrease starchy vegetables and fruits; Increase healthy fats; Eat only twice daily, and allow 12-16 hours of fasting overnight.

Veggies & More Veggies

There’s a lot of hype and misinformation about “going paleo.” But the core concept is simple: minimize processed foods, grains, and dairy, and eat what people ate for eons before agriculture: leaves, roots, berries, seaweeds, wild meats, and fish.

Though animal proteins and fats play an important role, Wahls is not suggesting that patients should eat prime rib and halibut at every meal. Vegetables, not meat, should take center stage.

“Three cups is a dinner plate, heaped high,” Wahls explains, acknowledging that 9 cups per day is a lot of plant material. But that’s the point: you want to maximize nutrient density. Good hunter-gatherer style diets have higher nutrient density than the American Heart Association diet and other officially sanctioned “healthy” diets, she notes, pointing to a 2004 study by O’Keefe and colleagues (O’Keefe, et al. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2004; 79(1): 101-8).

Following the Wahls diet will markedly reduce intake of toxins, sugars, trans-fats and potentially allergenic and pro-inflammatory triggers, while greatly increasing intake of vitamins, minerals,  micronutrients, and fiber. Whether or not it impacts MS directly, it will inevitably confer some health benefits, especially in patients who’ve been eating poorly.

micronutrients, and fiber. Whether or not it impacts MS directly, it will inevitably confer some health benefits, especially in patients who’ve been eating poorly.

In Wahls’ own case, the changes were as rapid as they were remarkable.

Three months after starting on her self-styled, veg-rich regimen, she was able to walk between exam rooms with only one cane. At four months, she could walk throughout the hospital without a cane or assistance. At five months, in 2008, she rode her bike for the first time in a decade. In 2009, she did a trail ride in the Canadian Rockies.

“When I first met Terry Wahls, she was wheelchair-bound and was happy if she was able to sit upright in her chair instead of laying flat,” said David Jones, MD, IFM’s founder, as he presented Wahls with the organization’s highest honor: the Linus Pauling Achievement Award. “To say, “She got a lot better” is a major, major understatement.”

Reproducible Responses

Skeptics might be inclined to write off Wahls’ story as an anomaly, a curious one-off case with no direct relevance for most patients. But she and her colleagues have a notable track record for reproducing Wahls’ success in their patients, some of whom are indigent and living on food stamps.

Food is central to Wahls’ interventions, but it is only one component. Attenuation or reversal of MS requires a multi-modal approach involving exercise, stress management, toxin reduction, treatments to improve sleep, and in some cases physical modalities such as neuromuscular electrical stimulation (e-stim).

Though her protocol is not a silver bullet, and does not work for every MS patient, the majority experience very real improvements in their health and functional status. Some have remarkable recoveries of lost function and arrest of disease progression.

“When I first met Terry Wahls, she was wheelchair-bound and was happy if she was able to sit upright in her chair instead of laying flat. To say, “She got a lot better” is a major, major understatement.”—” David Jones, MD, founder, Institute for Functional Medicine

In 2017, she and her colleagues published a series of papers documenting the impact of their interventions.

In one pilot project, the Iowa researchers assessed walking performance in 20 progressive MS patients on the Wahls protocol (Paleo diet, supplements, stretching & strengthening exercises, electrical stimulation, meditation, and massage) over a 12-month period. At baseline, the patients had a mean Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 6.2.

At 12 months, 50% showed significant 3-4 time-point improvements in their “timed up and go” (TUG) tests. Over the study period, these “TUG responders” also showed a mean 31% decrease in TUG times, and a 30% increase in mean 25-foot walk speed. In the TUG non-responders walking capacity deteriorated over the 12-month period (Bisht B, et al. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2017;7:79-93).

Not surprisingly, those with the more severe baseline disability levels were less likely to show gait improvements.

In a separate pilot trial, Wahls’ team studied impact of the paleo diet alone in 34 people with relapsing-remitting MS. The patients were randomized to an intervention group that adopted Wahls’ veg-rich, grain free diet, and a control group that continued with their customary diets. Seventeen people (8 paleo; 9 control) completed the study.

Compared with the controls, those on the Wahls diet had significant improvements in their Fatigue Severity Scale scores, MS Quality of Life-54 assessments, and 9-Hole Peg Tests. They also showed increased exercise capacity, improved hand and leg function, and increases in serum vitamin K (Irish AK, et al. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2017;7:1-18. 2017)

In a third paper, Wahls and colleagues compared people on the complete Wahls protocol (paleo diet, exercise, e-stim, stress management) and similar MS patients who made no diet or lifestyle changes. They found that the former had marked improvements in measures of anxiety (Beck Anxiety Inventory), depression (Beck Depression Inventory), cognitive function (Cognitive Stability Index, Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System) and executive function (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale).

Statistical analysis suggested that the mood and cognitive changes were more closely related to the diet component of the program than the exercise and stress reduction. “Anxiety and depression changes were evident after just a few months, whereas changes in cognitive function were generally not observed until later,” they wrote (Lee JE, et al. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017 Mar-Apr;36(3):150-168).

Dr. Wahls and her team are currently running a large randomized trial comparing the Wahls Elimination diet versus the low fat, low meat Swank diet—the more widely known of the MS diets. The 36-week trial looks specifically at fatigue—one of the most prevalent and debilitating sequelae of MS (Wahls T, et al. Trials. 2018 Jun 4;19(1):309)

The trial is notable in that it is one of the first truly rigorous major studies of dietary interventions in MS, and the first to do a head-to-head comparison of two distinct diets.

For Wahls herself, there’s also an element of sweet vindication in her hard won research success: she now receives funding in part from the very organization that once banished her. Under pressure from its membership to pay closer attention to nutrition and lifestyle, the MS Society ultimately made a $1.5 million grant to her Wahls Institute

Total Commitment

For optimal outcomes, patients need to be all-in on the lifestyle change.

As word of her recovery spread and her clinic grew, so did demand on Dr. Wahls’ time and attention. “Because there got to be a long wait to see me, the “ticket” to see me was to agree to my terms, which is 100% commitment for 100 days. If you’re not ready that’s fine, work with our dietitian one on one. But if you want to be a part of the group experience with “the Dr. Wahls,” then you have to say, “OK, I’ll do it 100% for 100 days—gluten-free, dairy-free, and all those vegetables,” she said following a Grand Rounds presentation at the Cleveland Clinic.

“MS is just a name. Just because you know the name, doesn’t mean that you know what’s wrong.”

The group visit model is a key to making the Wahls protocol work on a practical level.

Initially, “I had one day per week to do this. There was immediately too much demand, so I started with small group visits. As I got more and more comfortable with this, the size of my groups could grow. Because the VA has a population base, we don’t have to worry about FFS or insurance models. Doing this as group visits made a lot of sense,” she said in the interview.

Social support is invaluable for MS recovery, Dr. Wahls stressed. Diets, lifestyle change, and other medical interventions play important roles. But people are much more likely to get better if they have loving, supportive people in their lives and strong reasons to live.

“I could not have done this without Jackie, my spouse,” Wahls told the IFM. “You need someone in your life who loves you so much that you cannot die. It can even be a pet.”

Her now-grown children were also essential in her recovery. “I had come to terms with becoming bedridden, possibly demented, and likely to be in chronic pain. But my kids were incredibly young and watching me. Was I going to teach them to give up? Or was I going to inspire them to keep going to work no matter what?”

Wahls’ regimen is strict, but there is a lot of room for customization. She notes that one of the limitations of research protocols is that they don’t leave room for tailoring. Her institutional review board stipulated that her study interventions be exactly what she followed during her own recovery. “I don’t have the ability to personalize it as well as I could if I were in a private practice, not constrained by a study protocol.”

In the future, she hopes to extend both her clinical research and the dissemination of her approach. She lectures frequently, and leads clinician training programs to help other practitioners implement lifestyle change for MS reversal.

One of the high points of her year is the annual Wahls Protocol Seminar and Retreat, a 3-day event in Cedar Rapids for MS patients seeking to reclaim their health.

She believes the discoveries she’s made about MS have implications for other neurodegenerative conditions, and she is currently working on developing a similar diet and lifestyle protocol for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS).

Some might argue that Dr. Wahls has done the impossible: reverse an “incurable” condition. But there’s nothing inexplicable about it. Driven by an unstoppable will to live, supported by her loved ones, and armed with a probing mind and willingness to think for herself, she kept searching and experimenting until she found what worked. In the best sense, she’s a true physician-scientist. For that, she is revered by many thousands of MS patients.

“MS is just a name. Just because you know the name, doesn’t mean that you know what’s wrong.”

END