Mast cell activation syndrome—a multi-system disorder characterized by aberrant activity of these key immune cells—is widely prevalent, and on the rise as the world becomes more toxic, infectious, and stressful, says Tania Tyles Dempsey, MD, a clinician who specializes in this common but mis-diagnosed problem.

The syndrome differs from mastocytosis or mast cell cancers in that it is not caused by excessive proliferation of mast cells. Rather, it occurs when normal numbers of mast cells are chronically and inappropriately triggered, explained Dr. Dempsey at the 2022 Integrative Healthcare Symposium.

A 2013 study suggested that roughly 17% of the general population of Germany had symptoms that fit the picture of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS). It tends to cluster in families; nearly 50% of all first-degree relatives of MCAS patients will also fit the pattern (Molderings GJ, et al. PLoS One. 2013).

“Consider MCAS in all the “idiopathic” chronically ill patients. And get a comprehensive history from birth.”

Tania Tyles Dempsey, MD

According to Dempsey, in most US medical practices—and especially in functional and holistic medicine—the prevalence may be as high as 50% of all patients.

Many people with MCAS go undiagnosed for years. That’s because there is no single definitive diagnostic test, the “official” criteria are new and constantly evolving, and the syndrome is inherently complex.

Defining MCAS

MCAS as a clinical syndrome emerged around 2010, when physicians and researchers recognized that many people have multi-organ symptoms consistent with mast cell activation, in the absence of abnormal mast cell proliferation, and distinct from mast cell-mediated allergic reactions.

Cem Akin and colleagues at the Division of Allergy and Immunology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, proposed the first MCAS diagnostic criteria in a landmark 2010 paper. Their early guidelines have been revised several times since, but the core principles remained consistent.

Signs and symptoms of MCAS may include flushing, itching, gastrointestinal disturbances (GERD, abdominal pain, vomiting), cognitive dysfunction and “brain fog,” anxiety or depression, rashes and skin lesions, wheezing or shortness of breath, unexplained systemic hypotension or sudden fluctuations in blood pressure.

These can appear in isolation or in any combination, and the manifestations are highly individualized. MCAS often co-occurs with chronic fatigue, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, joint hypermobility, and inflammatory autoimmune diseases.

According to a 2017 paper by Dr. Lawrence Afrin, a leading authority on mast cell disorders, and a colleague of Dr. Dempsey’s, the top 10 most common symptoms of MCAS are:

Fatigue (83%); Fibromyalgia (75%); Pre-syncope or Syncope (71%); Headache (63%); Urticaria or pruritus (63%); Paresthesias (58%); Nausea/vomiting (57%); Chills (56%); Migratory edema (56%); and Eye Irritation (53%).

Roughly half of all MCAS patients experience dyspnea, rashes, GERD, abdominal pain, or cognitive dysfunction (Afrin LB, et al. Am J Med Sci, 2017).

The diagnostic criteria are still evolving, says Dr. Dempsey. “This is a little bit like Lyme disease, where there were pioneers who created consensus criteria, and then other groups changed the consensus based on factors not previously appreciated.”

For example, early MCAS proponents stipulated that there must be evidence of a tryptase surge to make the diagnosis. Tryptase is constitutively expressed on all mast cells and it will be elevated in many—but not all–mast cell-related conditions.

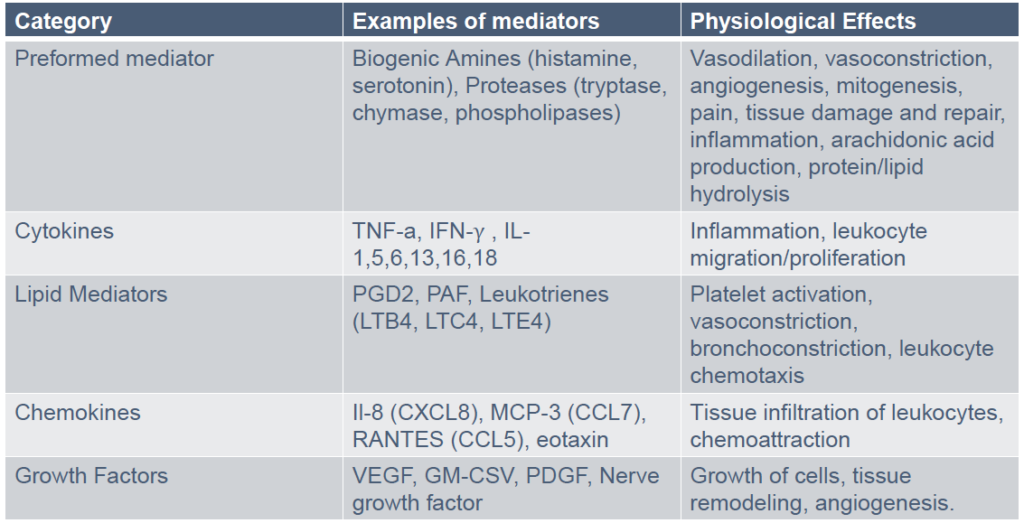

But mast cells produce other mediators besides tryptase. Reliance on just one to define the syndrome made little sense, said Dr. Dempsey, who heads the AIM Center for Personalized Medicine in Purchase, NY.

“Our new consensus dispenses with that exclusionary tryptase criterion. We look for elevations of any mast cell mediators that we can measure.” (See Breesi & Qeesi: Tips for Diagnosing MCAS)

To meet the current definition, patients must have symptoms consistent with chronic mast cell activation, which is abnormal at baseline, and/or reactive to specific triggers. Symptoms must be present in at least two organ systems, and all other diagnoses must be ruled out.

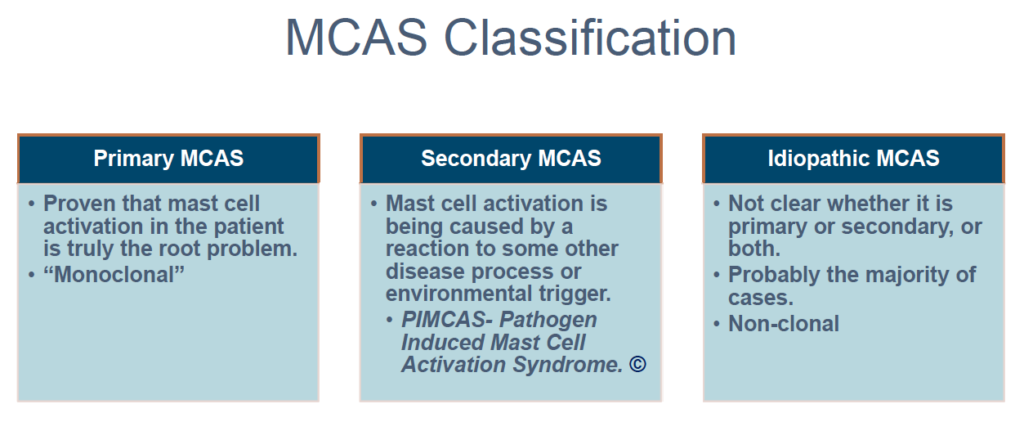

She described three general categories of MCAS:

Primary MCAS: in which mast cell activation best explains the constellation of symptoms, is definitively proven to be the root of a patient’s problems, and is “monoclonal” in the sense that it is related to a mutation—usually in bone marrow tissue–causing a clone of aberrant mast cells.

Secondary MCAS: in which mast cell activation is caused by an external environmental factor or infection. Lyme disease is a common culprit.

Idiopathic MCAS: in which it is not clear why the mast cells are activated. This represents the majority of cases.

MCAS patients may or may not have classic allergy or autoimmune symptoms. Though mastocytosis is distinct from MCAS, many mastocytosis patients also have aberrant mast cell activation which would meet the MCAS definition.

The triggers are myriad, and as diverse and individualized as the symptom constellations. Common ones include: air pollutants, pollen, extreme weather changes, emotional stressors, infections, mold, alcohol, specific foods, pesticides and environmental toxins.

One of the keys to managing MCAS—and one of the biggest clinical challenges—is to identify each patient’s specific triggers.

Dr. Dempsey noted that MCAS often overlaps with chemical intolerance: people who are highly sensitive to pesticides, fragrances, volatile compounds used in construction, and smoke may have MCAS and vice versa. Fungi and molds can also be triggers.

“Way Beyond Allergy”

“This is way beyond allergy. There are so many other things in which the mast cells are involved,” Dr. Dempsey told the IHS.

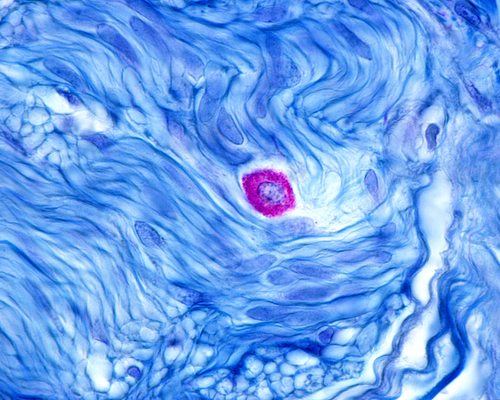

Formed in bone marrow, mast cells are released into the bloodstream and distributed into all vascularized organs, where they mature. That process is affected by epigenetic phenomena, and impacted by toxins and infections.

Mast cells are associated with blood vessels, lymphatics, smooth muscle, and epithelial tissue. They affect flow of blood & lymph, epithelial proliferation, wound healing, and tissue remodeling. They’re also intimately entwined with neurons, and in constant cross-talk with other immune cells. They drive activation, proliferation, and differentiation of B cells, influence the development of CD4 T-cells, and govern T-regulatory cell function.

They’re found in highest numbers in tissues that interface with the environment—the skin, airways, and intestines—where they can easily detect and bind pathogens. They can phagocytize bacteria, erythrocytes, metals, and foreign debris

Mast cells are quite heterogeneous even in a single individual; those in the gut produce certain mediators, while those in the respiratory tract produce others. They’re also highly adaptive to changes in their environment.

In women there are strong associations between hormonal shifts and mast cell changes over the menstrual cycle. Infections can change mast cell genotype and phenotype. Epigenetic factors like diet, environmental toxins, internal and external stressors also influence how they function.

Mast Cells, Neurons, and Pain

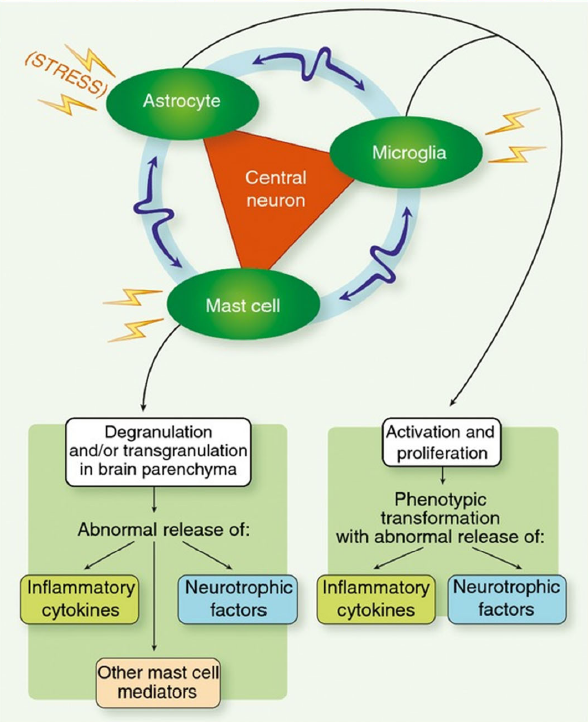

In the nervous system, mast cells reside near the nerve fibers and neuroglia. There’s a triangulation between them, the astrocytes, and the microglia. When mast cells degranulate, the nerves transmit signals very quickly.

Neurons and mast cells are integrated into a bi-directional interactive feedback system. The cross-talk between them can exacerbate acute neurodegenerative processes, explained Dr. Dempsey.

“Since mast cell activation disease patients often present neurological and psychiatric symptoms, neurologists and psychiatrists have the opportunity…to short-circuit the often decades-long delay in establishing the correct diagnosis required to identify optimal therapy.”

Lawrence B. Afrin, MD

Not surprisingly, MCAS often co-occurs with chronic pain syndromes—myalgias, endometriosis, vulvodynia, dyspareunia. “Mast cell activation contributes to neuroinflammation and neuronal autoimmunity. Treating the mast cell piece will resolve a lot of these things,” she said.

Back in 2015, Dr. Afrin posited that aberrant mast cell activation plays an etiological role in many neuropsychiatric disorders.

“Since mast cell activation disease patients often present neurological and psychiatric symptoms, neurologists and psychiatrists have the opportunity…to short-circuit the often decades-long delay in establishing the correct diagnosis required to identify optimal therapy.” (Afrin LB, et al. Brain Behav Immun 2015).

Several research groups have proposed that mast cell abnormalities underlie attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, a premise that warrants further study, though at this point it remains hypothetical (Song Y, et al. Exp Ther Med. 2020).

Theoharides and colleagues at Tufts University called mast cell activation the “missing link” in the development of autism—at least certain forms of it. That hypothesis is based on the finding that autistic children show elevated mast cell-derived mitochondrial DNA is elevated in their serum, which triggers powerful auto-inflammatory responses. Theoharides posits that autism may be “a sort of focal brain allergy.” (Theoharides TC, et al. Autoimmun Rev. 2013)

Anna Haiden, DO, a functional medicine practitioner based in Los Gatos, CA, and an MCAS patient herself, says she sees a significant overlap between MCAS and migraines.

“Mast cell degranulation starts a vicious cycle that both leads to and is fueled by the migraine syndrome,” said Haiden, who spoke on MCAS at the 2020 Integrative Healthcare Symposium. This clinical observation has been corroborated by brain MRIs.

“People with migraines show little spots in the white matter. People with MCAS often show the same little spots, as do some people with fibromyalgia,” said Haiden. “This is not specific to MCAS, but is a common co-occurrence, and it is a clue.”

There is also a link between mast cell dysregulation, irritable bowel syndrome, and related GI conditions. According to Robert Rountree, MD, who spoke at IHS 2022, most IBS patients show high levels of mast cell activation, as well as increases in mast cell-related mediators like histamine and various proteases.

“One etiology that is seen in about 10% of IBS cases is onset following a trip to a tropical or unfamiliar environment. They pick up a bug, and then there’s gastroenteritis, and inflammatory dysregulation long after the clearance of the infection. You won’t detect a pathogen, but the inflammatory process is in play and can’t be turned off.”

Integrative Treatment Strategies

MCAS is a complex, multi-system condition. It requires a multi-modal treatment program. There’s no magic pill, and the process is slow. But with careful identification of environmental and dietary triggers, and the right combination of treatments many MCAS patients experience marked symptom reductions and improved quality of life.

Dr. Dempsey and her colleagues typically use a combination of pharmaceutical, nutritional, and botanical therapies.

“It needs to be tailored. So, it will be different with each patient, but generally you’ll be using H1 blockers like loratadine, fexofenadine, certirazine, diphenhydramine, or hydroxyzine, and also H2 blockers like ranitidine, famotidine, or cimetidine.”

MCAS is a complex, multi-system condition. It requires a multi-modal treatment program. There’s no magic pill, and the process is slow. But with careful identification of environmental and dietary triggers, and the right combination of treatments many MCAS patients experience marked symptom reductions.

Low-dose naltrexone is often helpful, as are leukotriene inhibitors like montelukast, zafirlukast, or zileuton. But Dempsey stressed that for these patients it is best to get these drugs from compounding pharmacies, rather than in manufactured pill form. Ordinary pills often contain dyes to which MCAS patients may be sensitive.

Aspirin, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and COX-2 inhibitors are sometimes helpful, as are mast cell stabilizing drugs like cromolyn, ketotifen, and hydroxyurea. On occasion, she prescribes benzodiazepines, omalizumab, or imatinib.

On the non-pharma side, quercetin, luteolin, vitamin C, N-acetyl cysteine, alpha lipoic acid, and methyl-donating nutrients like folate, vitamin B12, and SAMe are major therapeutic allies. Some probiotic strains, particularly Lactobacillus rhamnosus, can temper histamine production.

The key therapeutic objectives are to stabilize the mast cells, reduce histamine release, quell inflammation, and address any underlying methylation deficits. The latter are common, though not ubiquitous, among MCAS patients.

No Clear-Cut “MCAS Diet”

“It is not easy and it is not fast. You have to try a lot of different things,” Dempsey said, acknowledging that this can be frustrating for patients and practitioners alike.

Also frustrating is the fact that there are dozens of different “low-histamine diets.” Most advise people to avoid citrus, fermented vegetables (sauerkraut, kimchi, etc), alcohol, cured or processed meats, aged cheeses, nightshade vegetables, and legumes. But they can vary widely in the specific foods they deem “histamine-producing,” and there are often contradictions between them.

As a rule, these diets are restrictive, confusing, and difficult to follow for the long term.

“We don’t have a hard-and-fast ‘MCAS diet,’” explained Dr. Dempsey. Since food triggers are highly individual, general diet guidelines often do not help. Part of the evaluation is to identify the specific foods to which each individual is especially sensitive, and then to focus on minimizing those.

The clinical understanding of MCAS is at an early stage, and still evolving. While the number of practitioners who specialize in this syndrome is growing, they are still few and far between. And since the evaluation and follow-up are time, labor, and test-intensive, MCAS care can be very costly for patients.

Dr. Dempsey urged practitioners to educate themselves about mast cells and the myriad roles they play, and to be on the lookout for MCAS.

“Consider MCAS in all the “idiopathic” chronically ill patients. And get a comprehensive history from birth,” she advised.

END