Last winter at the American Medical Association’s annual Interim Meeting, the physician’s group agreed to adopt a resolution that surprised healthcare professionals and members of the public alike.

The AMA House of Delegates — the organization’s primary policy-making body — voted in support of a proposed ban on direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising for prescription medications and implantable medical devices.

DTC pharmaceutical advertisements, which drug companies use to promote their prescription products directly to patients, saturate today’s media. From television commercials and radio spots to magazine spreads and online ads, this type of advertising has become increasingly prevalent in recent decades. It’s been cited as the most prominent type of health communication encountered by the general public (Ventola, CL. Pharm & Therap. 2011; 36(10): 669-674, 681-684).

While DTC ads may present some benefits to patients, educating them about various heath conditions and the available treatment options, many have argued that the ads are more detrimental to public health than they are beneficial. Responding to the heightened ubiquity of drug ads and the dangers they present, AMA leadership intends to spearhead efforts to make prescription medication use safer and more affordable for the patients who need it most. Elimination of DTC ads, they say, will further both objectives.

Ask Your Doctor About This Ad

DTC drug ads fall into three general categories. The first, called “product claim” ads, identify a condition to be treated alongside a prescription medication that’s defined by name. These ads present statements regarding the effectiveness of the named drug in treating the identified condition. Product claim ads must either contain information or refer to sources describing the risks associated with the drug.

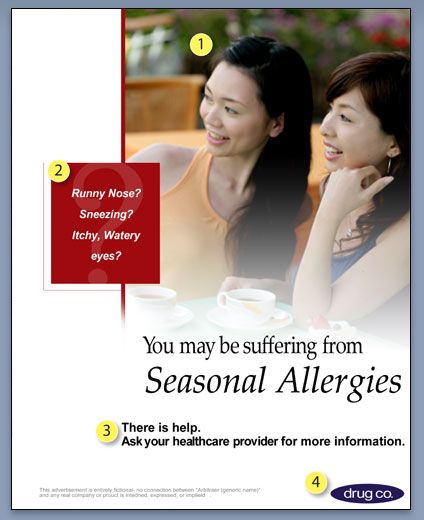

The other two types of DTC advertisements are “reminder” and “help seeking” ads. Reminder ads convey brand identification only and do not mention the health conditions for which a product can be used. Help seeking ads, also called disease awareness or “Ask Your Doctor” ads, recommend that patients experiencing specific health symptoms or diseases — seasonal allergies, fibromyalgia, and the ever-present erectile dysfunction being just a few examples — should consult with their physicians for more information (Wellington, A. Australasian Med J. 2010; 3(12): 749-766).

The Business of Health Media

Each year, drug manufacturers pour billions of advertising dollars into marketing their wares via all three forms of DTC ads. According to the market research firm Kantar Media, drug makers’ marketing expenditures have increased by 30% in the last two years, now totaling $4.5 billion annually.

Significantly, the United States and New Zealand are currently the only two countries in the world that allow DTC prescription drug ads that contain product claims. In most other countries, such ads simply aren’t allowed at all.

At the 2015 AMA meeting, physicians cited the proliferation of drug advertisements as one key factor that’s contributing to climbing drug costs. In a press release announcing the proposed ban, AMA Board Chair-elect Patrice A. Harris, MD, MA, stated that the group’s vote in support of advertising curtailments “reflects concerns among physicians about the negative impact of commercially-driven promotions, and the role that marketing costs play in fueling escalating drug prices.”

Similar sentiments have been echoed by other healthcare professionals. George D. Lundberg, MD, former Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of the American Medical Association, argues that “egregious drug price gouging and ubiquitous, misleading DTC ads…drive drug use and costs way up.”

2016 Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton has also spoken out against DTC advertising. On Clinton’s campaign website, she notes that if DTC ads aren’t regulated effectively, they can not only contribute to increasing prescription drug costs, but may also portray exaggerated claims and confusing or incomplete health information.

According to Clinton, the pharmaceutical industry should be held accountable for lowering drug costs and making prescription medications more affordable for patients. The largest pharmaceutical companies together earn $80-$90 billion annually in profits, at higher margins than other industries. Drug makers also receive billions of dollars in taxpayer support for conducting basic research — though they spend more on marketing than they do on R&D.

According to Clinton, the pharmaceutical industry should be held accountable for lowering drug costs and making prescription medications more affordable for patients. The largest pharmaceutical companies together earn $80-$90 billion annually in profits, at higher margins than other industries. Drug makers also receive billions of dollars in taxpayer support for conducting basic research — though they spend more on marketing than they do on R&D.

Meanwhile, the American public pays a hefty price for its meds. Charged thousands of dollars for novel drugs — and often at significantly higher costs than in other developed nations — a growing number of Americans are struggling to make payments on medical bills.

Clinton’s plan includes the elimination of corporate write-offs for DTC advertising, which she argues will save the government billions over the next decade. Eventually, she hopes to establish a mandatory FDA pre-clearance process for DTC marketing funded through user-fees paid by drug companies, ensuring that ads provide clear, understandable, and truthful information.

Overlooking Safer, Cheaper Alternatives

In addition to driving up drug prices, pharma ads can also prompt patients to request treatments that are not only costly, but often unnecessary or potentially harmful. While the drug industry claims that DTC ads empower patients to make informed decisions, Dr. Harris notes that delusive “direct-to-consumer advertising…inflates demand for new and more expensive drugs, even when these drugs may not be appropriate.”

Furthermore, DTC ads can put pressure on physicians to prescribe drugs, whether or not it’s truly advisable to do so. The ads may also cause patients and their doctors to overlook less expensive, safer, and equally — if not more — effective treatment options.

DTC ads have also come under fire for promoting off-label uses of drugs.

In March of 2015, consumer advocacy group Public Citizen sent a letter to Thomas Abrams, MD, director of the FDA’s Office of Prescription Drug Promotion (OPDP), asking Abrams to “stop the apparently violative off-label promotional statements in the [DTC] advertisements of five prescription drugs approved for the treatment of Type 2 diabetes.”

Public Citizen argues that ads for the drugs in question all contained statements describing the medications’ alleged weight-reducing properties, although none of them were actually approved for weight loss. “Despite the presence of disclaimers that the medications are not weight-loss drugs,” the group wrote, “the implication is clearly that weight loss is an additional potential benefit of the drugs. The deliberate placement of the claims in such close proximity to the drugs’ approved indications serves to reinforce this impression.”

Banning DTC drug ads would obviate this problem.

Prohibiting DTC Ads

The AMA’s effort to prohibit DTC pharma advertising raises a number of complex questions about media censorship and freedom of speech. There are also practical questions about how such a ban would be implemented, and whether it would it also extend to the marketing of other health products such as vitamins or supplements.

In 1976, the Supreme Court determined that the Constitution’s First Amendment, which protects individual freedom of speech, also applies to so-called commercial speech — a form of communication that proposes an economic transaction (Kessler, S. et al. Innov Marketing. 2013; 9(2): 69-75). DTC ads are considered to be a form of commercial speech, entitling them to protection under the Constitution.

Pharmaceutical ads in the US are specifically regulated by a set of laws outlined in the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA). Originally passed by Congress in 1938, the FDCA grants authority to the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to oversee the safety of food, drugs, and cosmetic products.

Prohibiting DTC prescription drug ads altogether would require an act of Congress in order to change the FDCA.

While the AMA has taken an important first step in that direction, an all-out ban would require significant lobbying efforts — which would surely be met with tremendous and well-funded resistance from Big Pharma.

Even if a ban were to pass constitutional muster, it would likely be years before any new laws could actually take effect. Some have argued that the AMA may be better off reaching a compromise with drug makers to tighten some of the regulations surrounding DTC advertisements, rather than pushing for a complete ban.

Either way, this is just the beginning of what’s sure to be a lengthy and interesting fight.

END