|

|

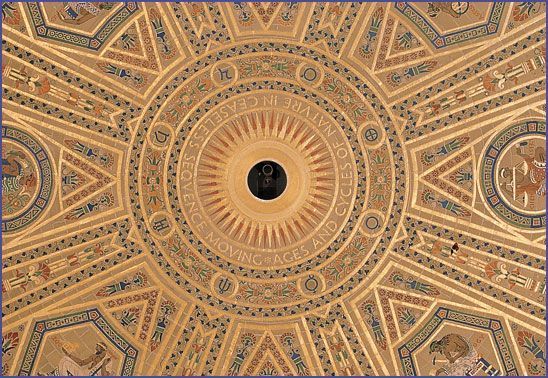

| “Ages and Cycles of Nature in Ceaseless Sequence Moving.” Guidance and inspiration for the future of integrative medicine are present in the words and images of Hildreth Miere’s painted dome in the Great Hall of the National Academy of Sciences, site of the Institute of Medicine’s landmark Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Public Health. Photo by JD Talasek, National Academy of Sciences. |

WASHINGTON, DC—There was a lot of talk about revolution and reform at the Institute of Medicine’s historic Summit on Integrative Medicine and the Public Health in February.

But there’s another “R” word, one that will determine how any future healthcare system functions, and what it will really deliver. That word is “reimbursement.” And while the IOM’s delegates were united in their view that US health care needs a radical shift toward prevention, there was far less consensus on how that transformation will be financed, and who will be fiscally empowered to provide integrated preventive health care.

Held at the ornate headquarters of the National Academy of Sciences, the IOM Summit convened leaders of the integrative/holistic medical movement, along with major players from academia, healthcare policy, the insurance industry, and the private sector. The goal? To define and clarify what, exactly, “integrative medicine” really is, and how it fits into public health and reform agendas.

The meeting was sponsored by the Bravewell Collaborative (www.bravewell.org), a private philanthropy dedicated to furthering the evolution of integrative medicine. It was an opportunity for some of the best minds in the field to make the case for a range of holistic disciplines that could engender a culture of wellness and personal empowerment, and help prevent or at least delay many of the chronic diseases compromising the nation’s physical and fiscal health.

Noble Sentiments. No Bull?

With the Obama administration’s hints at major healthcare reform echoing through the halls, the air was ripe with optimism that the moment has finally arrived for a meaningful move toward preventive medicine and greater acceptance of nutrition, botanicals, mind-body techniques, massage, acupuncture and other non-allopathic approaches.

“For those of us who have been working for years to promote wellness, our time has come,” Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA) told the roughly 700 delegates. He added that Pres. Obama “gets it,” about prevention, nutrition, and the need to change the focus from late stage disease treatment to life-long health promotion.

While the main goal of the Obama reform is universal insurance coverage, Sen. Harkin said prevention and wellness are central to the president’s approach. “It’s not enough to talk about how to extend insurance coverage. It makes no sense to try to figure out how to pay the bills on a system that’s broken and unsustainable. If we pass healthcare reform without infrastructure for health and wellness and prevention, we will have failed America,” Mr. Harkin said. Though he is confident about the ultimate triumph of wellness-centered reform, he was also very frank that the entrenched interests of the pharmaceutical, insurance, and mainstream medical industries will likely oppose major change.

You Say You Want a Revolution …

According to Ralph Snyderman, MD, Chancellor Emeritus of Duke University, and head of the IOM Summit’s planning committee, big change is inevitable. He said we are on the verge of “a new revolution in health care,” driven by advances in genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, systems biology, and nutrition science. These are converging to create a clearer picture of how gene expression and disease development are driven by environmental and lifestyle factors.

“We’re moving away from the belief that disease is caused by a (single) factor and that your job (as a doctor) is to find that factor and fix it. This reductionist approach has its place, but it is not sufficient. We should not be thinking simply of preventing disease, we ought to be talking about enhancing health and well-being.” That, he added, would be a revolutionary shift in medical thinking.

Dr. Snyderman wasn’t the only one talkin’ ’bout revolution. In a burst of surprisingly populist rhetoric, Reed Tuckson, MD, Executive VP and Chief of Medical Affairs for UnitedHealth Group, declared, “It’s time for a revolution. We’re all in this together.” He said UHG is committed to evidence-based, wellness-focused care.

However, he was equally forceful in stating that integrative medicine advocates are dreaming if they think insurers—and the large employers who pay them —are going to cover anything new without reams of good outcomes data. He said UHG is working closely with 8 integrative care sites funded by the Bravewell Collaborative, to study best practices and gather data.

Dr. Tuckson had scathing criticism for America’s healthcare gluttony. “Everybody wants everything all the time. The person who’s sick wants it all, and they want it now. The doctors want it all. The tech people want it all. And you should see what’s rolling down the hill from the geneticists.”

Left out of his Glutton’s Roll Call, however, were insurance industry executives who’ve reaped record salaries and bonuses over the last decade, despite the looming healthcare crisis. It was difficult to accept revolutionary repartee from a man who heads one of the country’s most rapacious insurance companies. Last year, UHG’s former CEO, Dr. Bill McGuire, was indicted in a Dept. of Justice investigation for illegally timing his $1.6 billion in company stock options.

Throughout the Summit, there was much talk about the need for patients to change their lifestyles, their expectations, and their utilization of health care. There were calls for doctors to change their modes of communication and ways of practice, and for researchers to change their study paradigms.

But beyond a general invocation of the virtues of electronic medical records in streamlining healthcare administration and reducing error—a case eloquently outlined by George Halvorson, CEO of Kaiser Foundation Health Plans—there was little mention of the need to address the layers of administrative cost insurers add to the healthcare equation, their longstanding reluctance to cover truly preventive medicine or the dangerous entwinement of for-profit health insurers with the rest of the financial sector.

Balking at Balkanization

The Summit touched on many thorny issues: the need for new research models to assess complex holistic approaches that don’t fit the drug-oriented RCT model; the challenges of funding new modes of care in a down economy; defining scope of practice for non-MD professionals; and the difficulties of transcending historical enmity between practitioner groups to create cross-disciplinary working relationships.

If the meeting itself is an indicator of where we are on the road to integration, it is clear we’ve got a looong way to go.

With just one exception, all clinicians on the Summit faculty were MDs. There were no representatives of nursing, naturopathy, osteopathy, chiropractic, traditional Chinese medicine or any of the other Asian healing disciplines. The one non-MD clinician on the roster was Janet Kahn, PhD, director of the Integrated Healthcare Policy Consortium, and a massage therapist.

Many non-MD professionals attended, but their input was restricted to brief comments during Q&A periods and unofficial remarks during smaller breakout sessions. In many cases, they sounded like they were making impassioned pleas for inclusion of their professions under the integrative Big Top.

This was not lost on Tom Donohue, CEO of the US Chamber of Commerce. “You’re all petitioners, trying to get this or that sector included in the (health reform) bill,” he told the assembly. “You want your piece of the pie. The big question is, how much pie is there? And how much pie can we afford?”

Mr. Donohue’s observations were true enough, as far as they went. But they were hard to swallow at a time when many of the nation’s corporate chieftains—some of whom are, no doubt, members of the Chamber of Commerce—are petitioning the government for public “stimulus” money.

The interdisciplinary struggles for inclusion and recognition in the integrative world are not so different from similar battles between allopathic physicians’ groups, though from the outside, MDs seem unified and monolithic.

Mehmet Oz, MD, the holistically-minded cardiac surgeon who vice-chairs the Department of Surgery at Columbia University, decried the “balkanization” of medicine. Its fragmentation and ever-narrowing interests only engender conflict and mistrust, which in turn leads to unnecessary suffering, and tremendous fiscal waste. Practitioners and hospitals, he said, have been too focused on their own narrow needs, and not enough on their patients’. He believes it will be well-informed, health-savvy patients who will ultimately re-set priorities and bring disparate disciplines together.

Defining “Integrative”

One of the biggest challenges confronting the integrative movement is in defining what “integrative” really means. Like “complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)” before it, “integrative medicine” is a catch-all term of convenience coined by allopathic medical professionals to describe a process of coming to terms with healthcare professionals, procedures, and practices that have evolved outside the domain of conventional allopathic practice.

Harvey Fineberg, MD, President of the Institute of Medicine, said the term is a bit like “a Rorschach blot.” People may see very different things within it, and what they see tells you something about where they’re coming from.

Do the diverse healing disciplines typically called “integrative” or “CAM” really have anything in common, other than their “otherness” from allopathy? Dr. Fineberg believes they do. He sees several common principles: 1) An understanding that health is more than the absence of disease; 2) A recognition that health is influenced not just by physical or genetic factors but equally by emotional, psycho-social, environmental and spiritual aspects; 3) A focus on health maintenance and disease prevention as well as acute and chronic care; 4) An emphasis on inter-disciplinary collaboration; and 5) Acknowledgment of biological variation and the need to treat individuals, not statistical “averages.”

There is another commonality: a recognition of the inherent ability of the human body to maintain and restore optimal health, and a view that a clinician’s job is to facilitate that innate ability. Though this principle was not formally articulated at the Summit, it is central to a bill forwarded by the American Association of Naturopathic Physicians and several other organizations and introduced into the House of Representatives by Rep. Jim Langevin (D-RI) last summer. (For more on this, visit www.holisticprimarycare.net, and read “Natural Medicine & Healthcare Reform: Taking Our Places, Raising Our Voices [Naturopathic Perspective],” Vol. 10, No. 2, Summer 2009.)

Tracey Gaudet, MD, Executive Director of Duke Integrative Medicine, said that integrative medicine represents, “a total change of mindset.” It is not about incrementally adding this or that “alternative” modality, but about re-thinking what health care could be. “The current healthcare model does not work because we are starting from the wrong place. We need a radical departure from the problem-based, disease-oriented approach.”

In practice, this obliges physicians to really get to know their patients, not just their chief complaints and lab values. “What gives someone meaning and purpose? If you can’t identify sources of joy in their lives, then nothing really changes. But if you do touch this, you can activate (the patient’s) true motivation for change. If you really get this, you’ll quickly realize that no aspect of the current healthcare system is set up for that.”

Coach Class

The decimation of primary care was of great concern to many at the Summit. At best, only 1–2% of all recent med school grads are going into primary care, a trend analysts say could sorely compromise large-scale reform.

Some speakers view integrative medicine as a springboard for re-invigorating primary care, if—and it’s a big if—federal programs and insurers were willing to pay doctors to practice that way. “Primary Care has the mindset, orientation, and relationship with patients required as a foundation for integrative healthcare,” said Edward Wagner, an internist and Director of the MacColl Institute for Healthcare Innovation. “We need to make a priority of saving primary care.”

Others argued that most doctors are neither well-trained nor well-positioned to do the health promotion work so many people need. They see credentialed non-physician health coaches as the key players when it comes to guiding and supporting people in making lifestyle changes.

“Even if we graduated 50% of all medical students into primary care, it would not fundamentally change the situation until we redefine, broaden and re-align the reimbursement. Nurses, physician assistants, health coaches all have a place, and it all needs to be expanded,” said Vic Sierpina, MD, Professor of Family Medicine at University of Texas, Galveston, and a member of the IOM Summit planning committee.

Health coaches—and there are now several formal credentialing programs for them—are not tied to clinics, so they can work with people in their homes, schools, gyms, workplaces. A number of corporations have implemented employee wellness programs with certified health coaches in the point positions.

Duke’s Dr. Gaudet is a strong advocate of health coaching. “It has really caught on recently. The concept really lands with people. I’d like to see health coaches take center place in the care team,” she said. “A coach can work directly with a patient to help implement and stick with lifestyle changes” recommended by his or her physician. She called for establishment of standardized core competencies and a universally recognized coaching credential. She and her colleagues at Duke are working on developing a curriculum for integrative health coaching.

Symbolic or Substantial?

Many people in holistic/integrative circles viewed the IOM Summit as a watershed moment, the first time the healthcare orthodoxy has formally invited leaders of the integrative field to the “table” of mainstream medicine. The Institute, which issues policy recommendations to guide national healthcare legislation, has historically been very conservative and less than welcoming of “alternative” thinking. In that light, the gathering had huge symbolic significance.

At the same time, some attendees felt a deep frustration that it has taken epidemics of largely preventable diseases and the near-bankruptcy of our healthcare system, before mainstream medicine would undertake a serious dialog with those who think there’s more to medicine than drugs, surgery and acute care.

Efforts toward reform and integration will not take place in a vacuum, and they will not go far without recognizing the true drivers of chronic disease, and the matrix of socio-economic incentives that drive the existing healthcare systems. Sen. Harkin and other speakers at the Summit rightly pointed out that we cannot have meaningful changes in health care without meaningful reforms in agriculture, energy, education, and environmental policy.

Everyone present seemed to agree that it is high time we brought together the best that all the diverse healing arts and sciences have to offer. The difficulty will be in determining who gets paid, by whom, and how value in health care gets determined. But the wrangling over the details—there are many, and they are complex—must be guided by a larger, overarching vision of improved health for all, lest it deteriorate into mere turf-battling.

The National Academy of Sciences has a beautiful central hall, it’s domed ceiling adorned with gold-leaf paintings of astrological, mythological and alchemical images. If leaders of the Institute of Medicine wish to understand the essence of holistic/integrative medicine, they would do themselves a service by spending some time pondering the visions on that stunning dome. Hildreth Meiere’s paintings are all about the four elements, the mysteries of transformation, the ever-turning cycles of the natural world.

“Ages and Cycles of Nature In Ceaseless Sequence Moving” says the dome’s central inscription. As the dialog about integrative medicine continues, let us hope that those leading the way will raise their eyes to the big picture as they struggle with the all-important minutiae.

The Institute of Medicine will issue a formal White Paper summarizing the Summit in November. Review and analysis of the presentations are available at the Bravewell Collaborative’s website: www.bravewell.org. Video recordings of all the sessions are posted at: www.imsummitwebcast.org.